Gruesome Examples Of Cannibalism Throughout History

When it comes to the taboos of the Western world, cannibalism is pretty high up on the list. (Among humans, at least — according to National Geographic, it's a normal part of life for countless animal species.)

The most famous instance of cannibalism in the U.S. is the Donner Party, when 60 members of a wagon train heading west got stranded in the Sierra Nevada during the long, unforgiving winter of 1846, and consumed the flesh of their companions in order to give themselves a chance at making it through those long, dark months. That, says National Geographic, is called survival cannibalism — and it's a not-unheard-of last resort. (Fun fact: Future president Abraham Lincoln nearly joined the Donner Party, but his wife vetoed the idea.)

Members of the Donner Party recorded instances of cannibalism in their journals and diaries, and it had been a desperate last resort. But they're not the only ones to turn to eating human flesh. Throughout history, there have been scores of instances where people have opted to dine on other people — and it hasn't always been a bid for survival.

China's Cultural Revolution

During the 1960s, Mao Zedong kicked off China's so-called Cultural Revolution in an attempt to secure his power. According to The Guardian, the movement — led by a group called the Red Guards — pitted citizens against citizens, and as many as 2 million people died. It wasn't until 1993 that The New York Times reported on recently released documents detailing widespread cannibalism, practiced particularly in the Guangxi Province as a way for revolutionaries to demonstrate their superiority over their defeated enemies.

The contents of the documents — which were prepared by government officials — were shocking, and included descriptions of students who murdered, cooked, and ate authority figures at their schools. Participation in the slaughter and butchery was seen as a way to show solidarity with the cause. Bodies were reportedly strung up in government-funded cafeterias, their flesh served to workers.

Numbers are inexact. Reports suggest that at least 137 people were killed and eaten, but it's estimated that their flesh and organs were distributed to thousands of people. Atrocities were brought to light largely by one person: Writer and activist Zheng Yi, who had already incurred the wrath of Chinese officials for his involvement in the Tiananmen Square protests, used his access to Communist Party records to not only document what had happened, but to find and speak with those who had participated in the slaughter ... and the ensuing feasts. Zheng wrote a book on his findings, and in 1996, The Washington Post reported he was living in exile in the U.S.

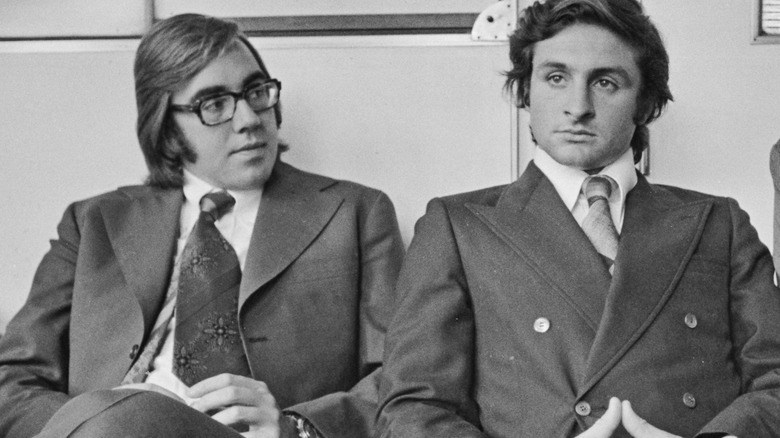

Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571

A reference to Uruguayan Air Force flight 571 might not ring any bells, but the movie that was based on it certainly will: "Alive." The incident started, says the Independent, when a plane carrying an amateur rugby team from Uruguay crashed in an area of the Andes called the Valley of Tears. The crash happened on October 13, 1972, and the 16 survivors (of 45 passengers and crew members) wouldn't be rescued until two days before Christmas.

One of those survivors was Roberto Canessa (pictured above right), who went on to become one of his country's top pediatric cardiologists. Just 19 years old at the time of the crash, he spoke to National Geographic in 2016 while promoting his book, "I Had to Survive."

Canessa was a medical student at the time, which meant he not only moved the bodies of the dead, but carved the flesh for eating. Once he'd wrapped his head around what he needed to do, it was almost all right: "I thought, if I were killed I would feel proud that my body could be used for others to survive. I feel that I shared a piece of my friends not only materially but spiritually, because their will to live was transmitted to us through their flesh." After they were rescued, Canessa visited the families of every person who had died in the accident. None, he said, judged them for what they had done (per The Washington Post).

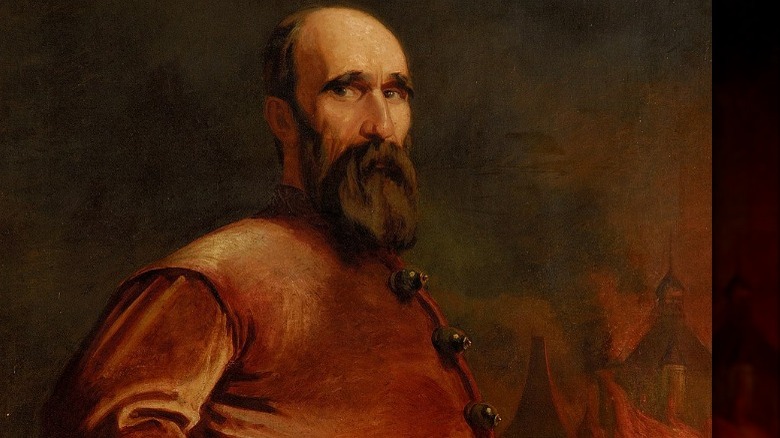

The execution of Gyorgy Dozsa

According to Britannica, György Dózsa led an army of peasants in a revolt against the Hungarian nobility in 1514, and he came close to winning it all. When Dózsa was finally captured, Edwin Lawrence Godkin's "The History of Hungary and the Magyars" reports that he was captured alive and mocked with a promise of a crown ... which, technically, he did get — red hot and right off the smithy's forge.

He was given a throne, too, that was just as hot — although the text doesn't recount whether or not it was hot enough to cook the flesh that was sliced from Dózsa's body while he was still alive. Those chunks were thrown to 14 other men who had been captured along with him: As punishment for their decision to follow the rebel leader, they were told to eat him. In "The Routledge History Handbook of Medieval Revolt," Paul Freedman writes that refusal to cannibalize their leader was punished by death, but it's entirely possible it was easier than it sounded; the men hadn't been given food for the 10 days leading up to the gruesome execution. They were also commanded to dance while Dózsa was executed, beheaded, and quartered.

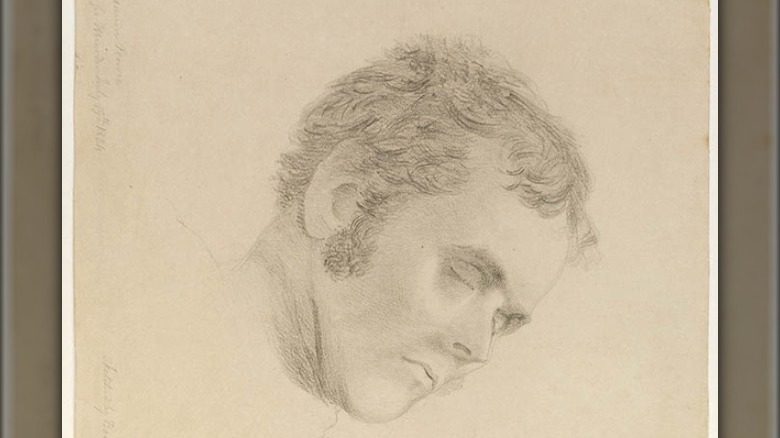

Alexander Pearce

According to Convict Records, Alexander Pearce was sent to Australia in 1819 after a conviction for stealing some boots. According to the National Centre of Biography, he had been sentenced to a series of lashings and hard labor for a variety of crimes until finally being sent to the Macquarie Harbour penal settlement.

While he was there, he formed an unlikely alliance with seven other convicts, and the men escaped together and set off across hostile, unforgiving territory. It's the sort of place, reports News.com.au, that still has a dangerous reputation today, and for ill-equipped fugitives in the early 19th century, it was deadly — especially considering the biggest threat was traveling with them.

The gang made it 15 days with no food before they drew straws to see which of them would be killed and eaten first. After the first round of cannibalism, one man took off on his own, and another died of exhaustion. One by one, the others were killed until only Pearce remained — and since no one believed the story he told when he was captured again, he was sent back to Macquarie ... only to escape again, in the company of a man named Thomas Cox. When he was recaptured yet again, they had reason to believe his story about killing and eating Cox, as bits of the man were still in Pearce's pockets. He was tried, found guilty, and hanged; his skull is currently part of a collection at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

Corpse medicine

The idea of preparing and administering pieces of the human body as a cure for various ailments is something that sounds completely fictional. It's very real, though, and according to research published in The Lancet, it's a kind of cannibalism that can be traced back 2,000 years. It started with ancient physicians who thought drinking the blood of gladiators would help restore vitality to ailing bodies. From there, physicians took the idea and ran with it.

There's almost no end to the ways in which humans were prepared. The pioneering Swiss-German physician Paracelsus thought fresh bodies were best; Germany's Johann Schroeder preferred the corpses of young men who died a violent death. Their flesh was often smoked, cured, and eaten as a sort of elixir of youth, while others were fed preparations made from ground skulls to treat convulsions. (The blood of an executed man was also drunk in the hopes of curing epilepsy.)

Research from the Folger Shakespeare Library found scores of recipes for adding body parts to homemade medicines. Among the most popular was using powdered skull to treat seizures, with some even specifying that the head should be thoroughly washed and dried "in a window" first. While it wasn't absolutely necessary for this so-called medicinal cannibalism to work, it was often advised that men should eat men, and women should eat women.

The whaleship Essex

According to Smithsonian Magazine, Herman Melville's "Moby Dick" was inspired by a very real incident. Melville met the real-life Captain Ahab — a man named Captain George Pollard Jr. — after the publication of his book.

Pollard and the Essex set sail in 1819, on a two-and-a-half year trip that was almost immediately beset by misfortune. The ship's troubles culminated in a November 1820 incident when a whale — estimated to be around 85 feet long — caught sight of the ship and rammed it, smashing a massive hole in the side. The 20 men on board split up into three boats, but they didn't head for the nearest set of islands because they were convinced the natives were cannibals. Instead, they headed out into the open ocean, where their provisions quickly ran out and they continued to be harassed by the whales they had set out to hunt.

First Mate Owen Chase (pictured) would later describe what happened to the first man to die: "[We] separated limbs from his body, and cut all the flesh from the bones; after which, we opened the body, took out the heart, and then closed it again — sewed it up as decently as we could, and committed it to the sea." The days dragged on, and they ate others as they died. When there were no dead men left, they drew straws: Pollard's nephew drew short, and was executed and eaten. The men in Chase's boat were rescued after 89 days; Pollard and one other survivor were rescued a week after that.

Daniel Rakowitz

It was 1989 when Daniel Rakowitz was looking for a new roommate. He was — according to what a local squatter named Jerry the Peddler told The Village Voice — "a classic nut. He had all the symptoms: he had sudden fits of rage, he had delusions of grandeur, he didn't like touching people, he had fantasy followers."

That roommate ended up being a Swiss dancer named Monika Beerle, and there's no telling whether or not she believed him when he said he was going to kill her. When his former roommate, Sylvia, stopped by to get some of her things, she recalled, "I went to the kitchen. And on the stove there was a pot. And in the pot was Monika's head. She was all burnt up, and her eyes were closed."

The rest of Beerle's remains were in the bathtub — at least, what was left. Rakowitz told Sylvia that he'd had no choice, and admitted that he'd eaten at least part of her brain. That was followed by other pieces of flesh he'd stored in the freezer, and even worse? Rakowitz was known for collecting donations of food and cooking massive meals for the homeless living in New York City's Tompkins Square, which is why it started circulating that he'd slipped some human meat into the regular meals. According to The New York Times, he was found not guilty of murder by reason of insanity, and in 2004, another jury decided he was "mentally ill but not dangerous."

Gough's cave

After the discovery of 15,000-year-old remains in Gough's Cave in Somerset, England, it was quickly determined that the bones belonged to individuals whose bodies had been butchered and then eaten. It took a few more decades to unlock more of the secrets these ancient ancestors had taken to the grave. According to The Guardian, it wasn't until 2017 that analysis was able to show that some of the distinctive cut marks weren't practical, but decorative. That led researchers to conclude this ancient group of hunter-gatherers had formal rituals around their cannibalism.

Silvia Bello of the Natural History Museum in London explained, "It's something we find horrifying, but ... that was their tradition. ... It was their way of disposing of bodies, like it or not."

A large percentage of the bones also showed bite marks, and over the years since the initial discovery in the 1980s, more remains have been discovered. In 2011, The Guardian reported on the discovery of three cups made from human skulls, including one that came from a child who was roughly three years old. However, there's another school of thinking that suggests this cannibalism had a practical side, too: The bones have been dated to the last ice age, and the fact that they were butchered using the same techniques revealed by patterns on animal bones has led to the conclusion that regardless of the motives, cannibalism helped humans survive the ice age.

The expedition of Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca

Bill Schutt is the author of "Cannibalism: A Perfectly Natural History." He told National Geographic that when European explorers started hacking, slicing, and enslaving their way through the New World, their justifications included rumors that the Indigenous peoples practiced cannibalism — and therefore, needed the strong European influence to change their ways. It's super interesting, then, to know that the first recorded instance of cannibalism in the New World happened among the Spanish explorers under Alvar Cabeza de Vaca.

Cabeza de Vaca's men had traveled from Florida and ended up in what's now Galveston, Texas. They called it the Island of Doom, though, and according to the Los Angeles Times, five of his men — referred to in his writings as "the Christians" — were separated from the others. He wrote that they "came to the extremity of eating each other," and noted that the native people who had started caring for the main group "were so shocked at this cannibalism that, if they had seen it sometime earlier, they surely would have killed every one of us."

If they had, they may have lived: The Spanish explorers carried diseases with them, and around half of the Indigenous people who helped them survive the Texas ordeal died themselves.

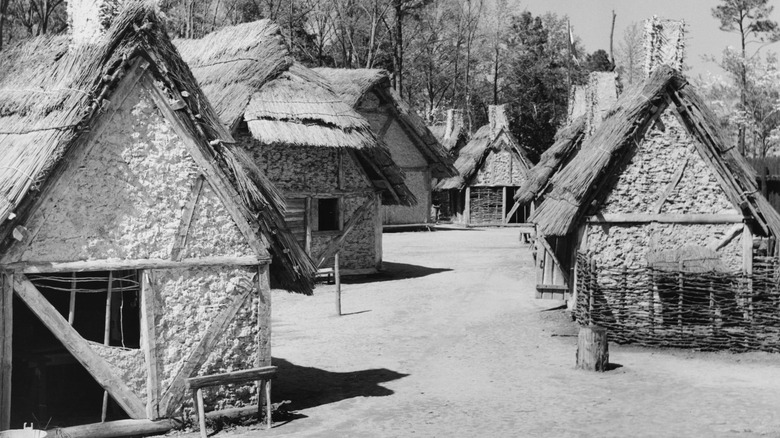

Jamestown

It's an oft-told tale that America was founded by people who were brave, adventure-seeking, and unbelievably tough, but were they cannibals? It turns out that some of them were. History notes that when the English first settled Jamestown in 1607, they were woefully ill-prepared for life in the New World. Starvation came quickly, and it wasn't long before neighbors started looking pretty tasty.

George Percy lived there during the eerily named Starving Time, and wrote in his journal, "Notheinge was Spared to mainteyne Lyfe and to doe those things which seame incredible, as to digge upp deade corpes outt of graves and to eate them." His wasn't the only account of cannibalism in Jamestown, but it wasn't until an archaeological dig started in 1994 that actual, physical evidence of cannibalism was discovered.

In 2013, National Geographic reported on the discovery of the remains of a 14-year-old girl, recovered from a trash pit dated to the Starving Time. Researchers named her Jane, and while it's not clear who she was, her skull and leg bones show distinct marks associated with the butchering of animals for food. They were able to determine that her face, tongue, and brain had been eaten, and it was also clear that the cut marks were hesitant — they were made by someone who didn't want to do what they were doing, but had no choice. Jane, they say, likely died of natural causes and was then butchered.

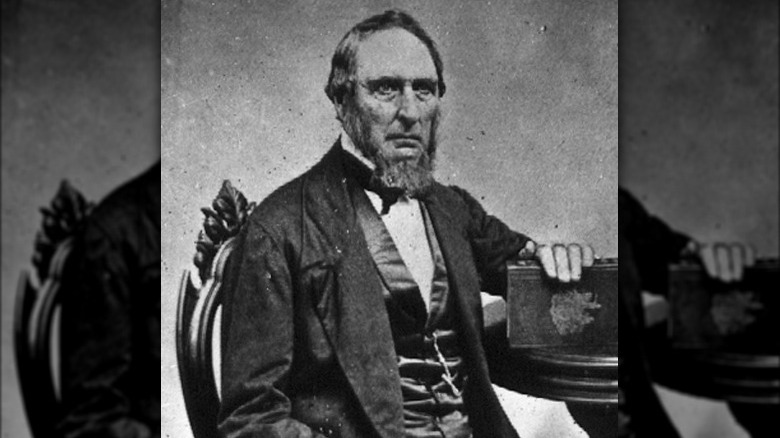

Francisco Leona

How far would a person go to save their own life? That was the question facing Francisco Ortega in 1910, and the answer was that he'd go pretty far — even at the cost of a child's life.

According to La Voz de Almeria, Ortega had contracted tuberculosis. So, he went to a local healer named Francisco Leona (pictured), and Leona had a cure ... albeit, a grisly one. With the help of an accomplice, he kidnapped and killed a 7-year-old boy named Bernardo Gonzalez, and harvested two ingredients that they believed would cure Ortega: the boy's blood and the fat from his abdomen, which was also called "the butters." The idea, says Periergeia, was that the afflicted person would drink the blood — which was drained while Gonzalez was still alive — and apply poultices made from the fat to his chest. It wasn't the first time such a crime had been committed in Spain, but it was one of the most famous cases. The Museum of the Civil Guard in Madrid even has a diorama of the arrest of Leona and his accomplices.

The crime left a long-lasting mark on the psyche of the area, and gave rise to the myth of a bogeyman that stalked the night looking for children to feast on.

Franklin's lost expedition

The idea of a Northwest Passage was a tantalizing one: In theory, traveling through the icy waters of the North Pole could cut a ton of time off trade routes, and in 1845, Sir John Franklin and his crew of 128 men on two ships — the HMS Terror and the HMS Erebus — set out to find it. No one saw any of them again.

According to LiveScience, the ships carried food that could be stretched for up to seven years, as they had fully expected to be stuck along the way. But they hadn't expected to be stuck for years: By the spring of 1848, 24 people had died, and survivors decided to start walking to safety. The problem? It was about 1,000 miles to get to the nearest trading post, with next to no food sources along the way. Over the years, remains from the crew have been found, and a close study of the bones (published in the Journal of Osteoarchaeology) confirmed that some bore signs of cannibalism. Specifically, they showed signs of something called "pot polishing," which happens when bones are broken and boiled to extract the last of the marrow.

Researchers from the University of California told Forbes that this was the first study that looked at the stages of cannibalism — and boiling bones for marrow is considered "end-stage cannibalism." The findings support eye-witness accounts from Inuit travelers who reported seeing piles of broken human bones, broken and boiled long after the meat was gone.