The Earliest LGBTQ+ Films In Hollywood Are Older Than You Realize

If you watch old movies, you might come away with the mistaken belief that folks in the early 20th century were naive and prudish. Old films went to sometimes-comical lengths to avoid depicting certain aspects of life, from sex to violent crime, leaving modern viewers with the impression that people didn't talk about — or perhaps know about — these things.

But they certainly did. As explained by PBS, the vanilla nature of some older films was the result of the Production Code, a self-imposed list of restrictions cooked up by film studios in response to growing criticism of the industry as a morally corrupt business. Not only were films released before enforcement of the Code beginning in the early 1930s absolutely filled with sex, violence, and other sordid stuff, but Hollywood itself had suffered several unsavory scandals involving accusations of rape, drug overdoses, and shocking divorces. The Production Code — often called the Hays Code after the man hired to be the face of the Code, Will Hays — was designed to rehabilitate Hollywood's image.

One result of the Production Code was the elimination of any hint of LGBTQ+ people in American films, making it seem like no one acknowledged the existence of LGBTQ+ folks until much later in the century. But before the Code, there were plenty of queer characters and themes in films, not to mention films from countries that were never under the thumb of the Code. In fact, the earliest LGBTQ+ films are older than you realize.

Algie, The Miner (1912)

As noted by The Baltimore Sun, in the early part of the 20th century, gay themes and characters weren't considered forbidden — they were actually pretty common. Often their queerness wasn't totally explicit, however. Instead, narratives often had superficial heterosexual and cisgender characters laid on top of queer stories that anyone in the know would recognize immediately.

One of the earliest films with obvious LGBTQ+ subtext is "Algie the Miner." Released in 1912 and directed by Alice Guy-Blaché, according to the "Encyclopedia of LGBTQIA+ Portrayals in American Film," the story follows Algie, an "unusually effeminate easterner," who is challenged by his fiance's father to prove that he's a real man. So Algie heads off to the frontier to do so, wearing a flouncy outfit and frequently kissing the men he encounters.

That Algie returns home after a year as a more traditionally hetero man doesn't change the fact that he's depicted as gay throughout the film. As noted by author Richard Barrios in the book "Screened Out," Algie's costuming and mannerisms were all designed explicitly to convey his orientation to the audience. At the same time, on the surface, Algie is heterosexual — he has a fiance, after all, and at the film's end, he has adopted a much more traditional masculinity. This allowed audiences to see what they wanted to see in the movie.

A Florida Enchantment (1914)

As noted by R. Bruce Russell in Cinema Journal, some modern descriptions of the 1914 film "A Florida Enchantment" makes efforts to position the film as a madcap comedy wherein totally straight people temporarily change genders and have comedic adventures. According to Film at Lincoln Center, the story focuses on heiress Lillian Travers, who comes into possession of magic seeds that transform people into the opposite gender. After a fight with her fiance, she takes a seed and becomes Lawrence; her fiance also eats a seed and becomes a woman.

What's key here, however, is that the change is internal. Lillian still looks like herself, she has only become a man on the inside. While the opposite genders, both Lawrence and her fiance eagerly romance members of the "new" opposite gender with a lot of enthusiasm, which to outside observers looks like lesbian and gay relations.

As author Janet Staiger writes in the book "Bad Women," the film does not simply portray cross-dressing as comedy (a fairly common trope in early films), but rather mines ambiguity around gender and orientation for its comedy — suggesting that both are more fluid than the audience might assume. As noted by author Siobhan B. Somerville in "Queering the Color Line," the film "provides an unusually sustained and unambiguous display of female homoeroticism." (Somerville also notes the film's unfortunate treatment of racial issues, which is very much not great.)

I Don't Want to Be a Man (1918)

As noted by the San Francisco Silent Film Festival, World War I prompted many women around the world to take on jobs and roles that were traditionally done by men. As a result, it became trendy to also dress in a more masculine way. This was reflected in films, where cross-dressing was a common comedic trope in the post-war era. The Guardian notes that cross-dressing in the age of silent films was also a tradition carried over from the theater, noting that the intended effect often depends on the gender of the actor: Women dress as men in order to gain freedom or privilege, while men dress as women to make people laugh.

So the story "I Don't Want to Be a Man" tells wasn't revolutionary at the time: A wealthy young girl (Ossi Oswalda) rejects the restrictions of her gender and dresses as a man in order to enjoy greater freedom. But as historian Robert Beachy notes in the book "Gay Berlin," what makes "I Don't Want to Be a Man" seminal in the history of LGBTQ+ films is that it features an explicit and intentionally gay kiss. The girl meets her own (male) tutor at a party, and he drunkenly kisses her while believing she is actually a young man. It's an overt queer moment — although one subverted by the film's ending, which sees the girl and her tutor becoming a more traditional heterosexual couple.

Different from the Others (1919)

One of the most important LGBTQ+ films ever produced, Advocate notes that "Different from the Others" not only tells a love story between two men, it explicitly argues for the acceptance of gay relationships. According to The New Yorker, the film is the first to depict a love story between two members of the same gender, a well-known musician and the younger man he takes on as a protege. The film was written by Magnus Hirschfeld, who the San Francisco Silent Film Festival notes was a doctor who founded the Institute for Sexual Research in 1919 and worked to fight back against censorship and to encourage understanding and acceptance of the LGBTQ+ community.

The Los Angeles Times reports that the film was written to protest a German law that made homosexuality a crime and basically legalized the blackmailing of LGBTQ+ people. The film reflects that stressful environment — the story is pretty dark. The main characters suffer from constantly hiding their relationship and pretending to be something other than what they are, and eventually fall victim to blackmail.

The Nazis destroyed prints of the film in 1933, but 40 minutes had been added to a documentary film and were discovered in Russian archives. The film has been restored as best it can be using still images and documentation to fill in the missing material.

Salomé (1923)

According to the San Francisco Silent Film Festival, the 1923 film "Salomé" is an adaptation of Oscar Wilde's 1891 one-act play and is regarded as almost entirely the work of actress Alla Nazimova and designer Natacha Rambova. Nazimova, who Tablet Magazine reports was openly bisexual in her private life, sank a significant portion of her own wealth into the production. The end result is what Datebook describes as "the world's first queer art film."

The film tells the biblical story of Salomé, King Herod's stepdaughter. When John the Baptist refuses her advances, she performs a seductive dance to convince Herod to have him beheaded. The design and performances combine to create a dream-like experience, with operatic physical acting and hallucinogenic sets.

Appropriately for a film based on a play written by a man who was imprisoned for being gay (per History), it has become an iconic film in LGBTQ+ Hollywood history. It's rumored that many of the minor female roles were played by men, and there are several performances in the film that are clearly intended to read as gay. (Film Forum notes that there is another rumor that the entire cast was "exclusively gay and lesbian.") But the film is mainly notable for its queer aesthetic, a style and worldview that remains instantly recognizable to LGBTQ+ audiences today.

Mikaël (1924)

Released in 1924, "Mikaël" is based on a novel by Danish writer Herman Bang, according to On Magazine. In his book "Queer Sexualities in Early Film," author Shane Brown notes that Bang was a gay man and that the film explores the relationship between an older artist and a young model that is easily interpreted as gay — author Paul Matthew St. Pierre describes it as a "film about artistic sensibility as well as homosexual love" in his book "Cinematography in the Weimar Republic."

The film's LGBTQ+ themes are subtext, however — nothing is explicit and, in fact, author Claude Summers notes in the book "The Queer Encyclopedia of Film and Television" that the relationship between the two men is implied and hinted at through the acting and not made obvious. It's also made clear that the young model is using the older man; he is depicted as taking advantage of the older man's wealth and position, and eventually blatantly pursues a relationship with an aristocratic woman, ultimately breaking the artist's heart. At the same time, Brown notes that the model's heterosexual relationship is presented as much less passionate and meaningful. When the artist dies, he forgives his lover for everything he's done and announces that at least he's known what real love is like.

Wings (1927)

On the surface, "Wings" is an unlikely film to be considered LGBTQ+ in any way. The film (which won the very first Oscar for Best Picture according to Oscars.org) is set during World War I and follows two pilots as they compete for the affections of a woman — a scenario that doesn't seem like it has much to do with LGBTQ+ issues at all.

But as Far Out Magazine points out, under the surface, it's a very different story. Because while ostensibly vying for a woman's love, the two male characters are depicted as forging a relationship that is clearly romantic in nature, and which culminates in one of the earliest same-sex kisses in Hollywood history. This relationship is presented as an intense wartime "friendship," and as Film School Rejects points out, it's possible that audiences at the time accepted this at face value, seeing no gay subtext at all. But to modern eyes, the fact that this is a gay love affair is pretty clear.

Many of the narrative decisions seemed designed to obey the content restrictions of the time while conveying the real story, to the point where the term "friendship" is used almost as a code word for gay love, making the scene where one man says "there is nothing in the world that means so much to me as your friendship" before kissing another man on the mouth land much differently than expected.

Sex in Chains (1928)

As the San Francisco Silent Film Festival explains, Wilhelm Dieterle's 1928 film "Sex in Chains" was primarily designed as a plea for prison reform. The author of the book the film was based on, Karl Plättner, was arguing that prisoners should be allowed conjugal visits. The movie depicts a male prison as a terrible place where the men go mad from being deprived of the regular stimulation of life — most notably sexual relations. The prisoners are shown sculpting female bodies from bread, hallucinating the women in their lives, and turning to homosexual relationships.

As author Alice A. Kuzniar notes in her book "The Queer German Cinema," the latter is what makes this film iconic in the history of LGBTQ+ cinema. The story involves a man named Franz, who has fallen on hard times with his wife. When she is assaulted, Franz defends her and winds up in prison, where he meets Alfred and slowly begins a gay relationship with him. However, their feelings persist when the men are released, and Franz realizes he can no longer return his wife's affections.

As with many silent-era films that portrayed LGBTQ+ characters, most of Franz's homosexuality is implied, and Franz is presented with traditionally "masculine" characteristics to further mask the truth of his relationship with Alfred. Still, to modern audiences, it is obvious that Franz and Alfred are gay — and could have been happy if they were allowed to be themselves.

Pandora's Box (1929)

As noted by Roger Ebert, "Pandora's Box" offers "one of the first obvious lesbians in the movies," a female character who finds the protagonist of the film, Lulu (Louise Brooks), irresistibly attractive. That's par for the course in the film — The Guardian notes that Lulu is presented as a naive young woman who doesn't seem to understand or be able to control the effect her beauty has on everyone around her, including women. Aside from depicting a female character as clearly gay, the film also includes a scene where she attempts to seduce Lulu — a scene that leaves nothing to the imagination about the character's sexual orientation and which was, in fact, frequently cut out of the film as a result.

Surprisingly, the inclusion of an explicitly gay character isn't the only reason "Pandora's Box" is regarded as an important example of early LGBTQ+ films. As noted by Paste Magazine, Lulu is presented as an androgynous character (Brooks' iconic bob haircut accentuates this) who refuses to be labeled or confined by the expectations of her gender — that she be chaste, that she be passive, that she play the role of dutiful wife. This resonates with anyone who has had reason to reject labels and expectations, especially around appearance, behavior, and the decisions surrounding who they love.

Mädchen in Uniform (1931)

According to The Criterion Collection, the first legit lesbian kiss depicted in a film is found in "Mädchen in Uniform" in 1931. While there had been same-sex kisses before, they were typically couched in a way that allowed for plausible deniability of the lesbian identity of the characters — whereas "Mädchen in Uniform" is all lesbian energy. In fact, as noted by Autostraddle, it's pretty much regarded as the first "lesbian film."

As authors Timothy Corrigan and Patricia White explain in the book "The Film Experience," the film's writer, Christa Winsloe, was a lesbian and based the film on her own play. The film is staged with an all-female cast and a female director (Leontine Sagan). And the story is itself avowedly queer — GO Magazine explains that the film is set at an all-girls boarding school, where the students all share an erotic fixation on a teacher. The protagonist, Manuela, finds her relationship with the teacher growing more and more intense — and physical. A pivotal moment in the film shows the teacher kissing each of her students good night on their foreheads until she comes to Manuela. Their kiss is on the lips and leaves no doubt as to their desire for each other.

The film isn't a total triumph in the history of LGBTQ+ film: Its setting at a school of young women and the power- and age-imbalanced relationship between student and teacher mars what could have been a triumphant cultural moment.

Queen Christina (1933)

As noted by NBC News, Queen Christina of Sweden, who ruled in the 17th century, has been the subject of much debate concerning her sexuality. While some see her androgynous appearance and strong affection for women as clear signs that she was a gay woman, others argue that this was more of a smear campaign targeting an unpopular monarch.

These rumors played into the 1933 film based on her life, starring Greta Garbo in the title role. As noted by Larry Gross in the book "Up from Invisibility," when the production was announced, journalists noted the historical references to homosexuality and wondered if the film would address it. But while the film did not portray Christina as an explicitly gay woman, it did portray her as wearing men's clothing and disdaining the company of men in favor of the women in her court, one of whom she kisses rather passionately. Furthering the film's LGBTQ+ themes, the queen eventually begins a relationship with a man, but he falls in love with her while she is pretending to be a boy.

"Queen Christina" may have hedged its bets concerning its LGBTQ+ subtext by having a more conventional relationship win out in the end (this worked — as noted by Patricia White in the book "Uninvited" it received little censorship attention), but the combination of Greta Garbo's androgynous image and Christina's masculine dress and interest in same-sex relationships makes that subtext quite clear.

Sign of the Cross (1934)

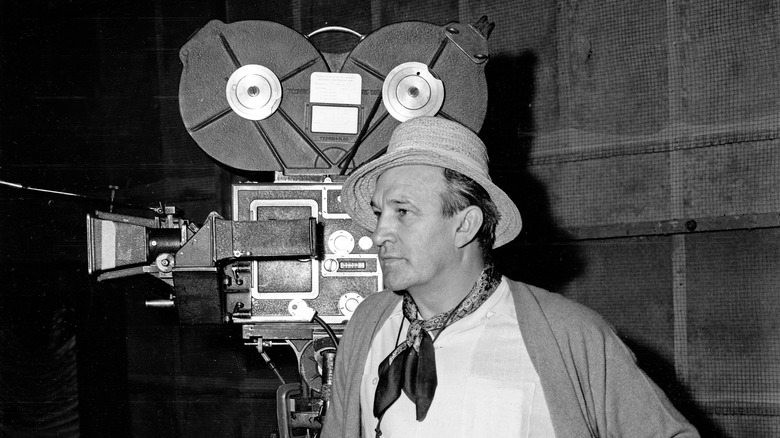

There are few early Hollywood names more famous than Cecil B. Demille. Britannica points out that he was a legendary innovator who pushed silent-era Hollywood to make feature-length films instead of focusing on shorts, then transitioned into the era of sound pictures and helmed some of the biggest spectaculars of the 1950s, like "The Ten Commandments."

Surprisingly, he was also responsible for some of the most important LGBTQ+ moments in early Hollywood — and even made a film featuring one of the most obviously queer characters of the time. In 1922 he released "Manslaughter," which author Richard Barrios points out in the book "Screened Out" is set in contemporary times but contained a strange scene flashing back to the fall of Rome, where a lesbian couple is pointedly shown to be making out passionately in what is one of the earliest depictions of an erotic same-sex kiss.

But 10 years later, Demille would top that with "Sign of the Cross," which Barrios notes was "the first major American film to create significant controversy over its homoerotic content." As reported by Screen Culture, the character of Roman Emperor Nero (played by Charles Laughton) engages in several instances of gay relations with a (mostly unclothed) enslaved boy — and there's even a dance sequence that contemporary reviewers knew full well was intended to be queer in nature.