Forgotten Union Generals From The American Civil War

For those who have studied United States history or are passionate Civil War buffs, the names of the best American Civil War generals are as familiar as the names of Hollywood stars or sports icons are to others. Of course, not everyone has studied history in-depth or is a Civil War buff. It's safe to assume that, for some, the only names that might ring a bell are those of Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee as well as perhaps some of the heavy hitters such as George McClellan, Stonewall Jackson, and William Tecumseh Sherman. After all, a 2015 survey by the American Council of Trustees and Alumni demonstrated that many, even in America, don't even know the basics about the Civil War: Only half of Americans could correctly identify when the Civil War took place, while only 18% knew the purpose of the Emancipation Proclamation.

With that said, it is never too late to learn. According to The New York Times, there were over 550 generals fighting for the Union against the rebelling Confederacy during the Civil War. Each man had his own path to promotion to general. For many, a path included West Point, but others included minimal military experience. Each had lives and loves, differing ideologies and strategic theories, and admirable qualities alongside glaring, sometimes shocking flaws. Below are just a few of the Union generals often overlooked and forgotten in textbooks.

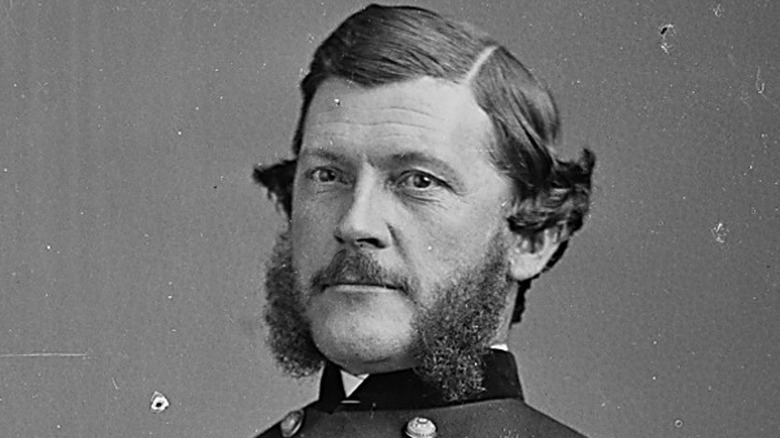

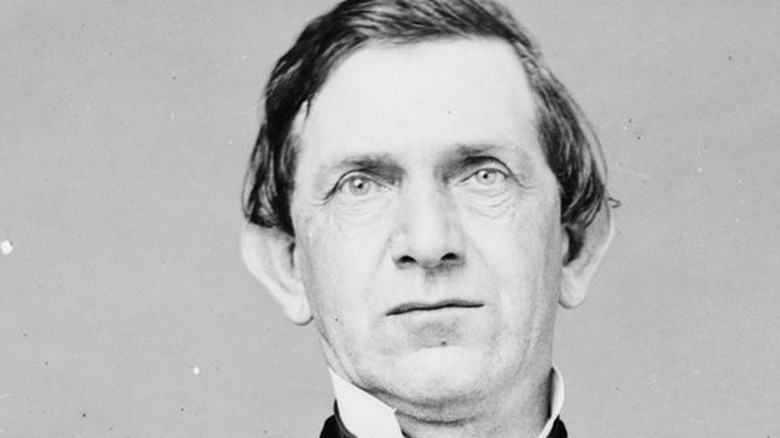

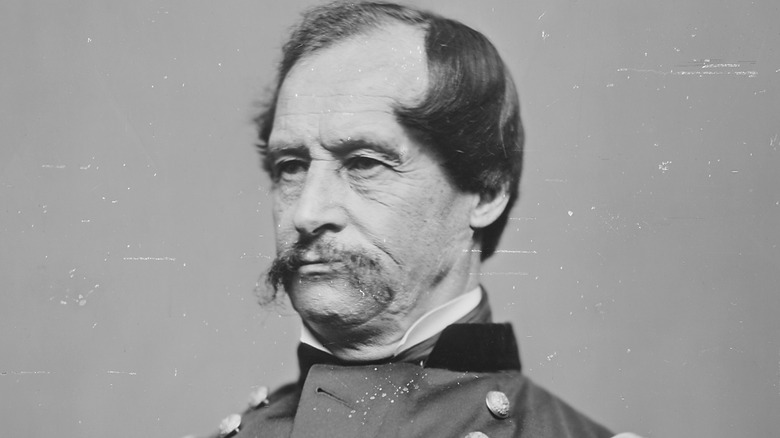

John G. Parke

John Grubb Parke, born in Chester County, Pennsylvania in 1827, was a West Point graduate and Army engineer who was surveying the precise boundary between Canada and the territory of Oregon in the years before the Civil War (per The Historical Marker Database). When war broke out, his surveying was put on hold. He was initially a captain in the U.S. Army Corps of topographical engineers but distinguished himself during the early campaigns of the war under the command of General Ambrose Burnside. In 1862, as described by the National Park Service, he was promoted to major general in charge of volunteers before then being transferred to oversee a division in the IX Corps, otherwise known as the Ninth Army Corps.

According to the American Battlefield Trust, a non-profit heritage organization sponsored by The History Channel, he commanded Civil War soldiers during the siege of Vicksburg as well as fighting in Jackson, Mississippi, and Knoxville, Tennessee. He would be in command of the IX Corp until the spring of 1865 when he was transferred to the XXII Corps in Alexandria, per the NPS. When the war ended, Parke then returned to his position with the U.S. Army Corps of topographical engineers, finished his surveying job between Canada and Oregon, and went on to lead West Point as its superintendent. He died in 1900 while residing in Washington, D.C.

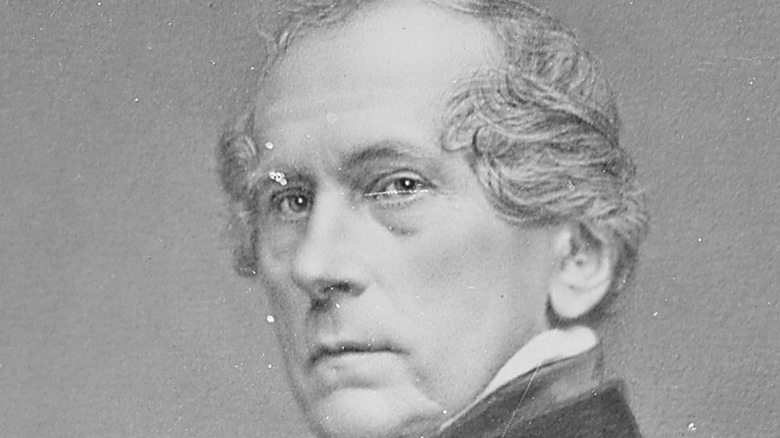

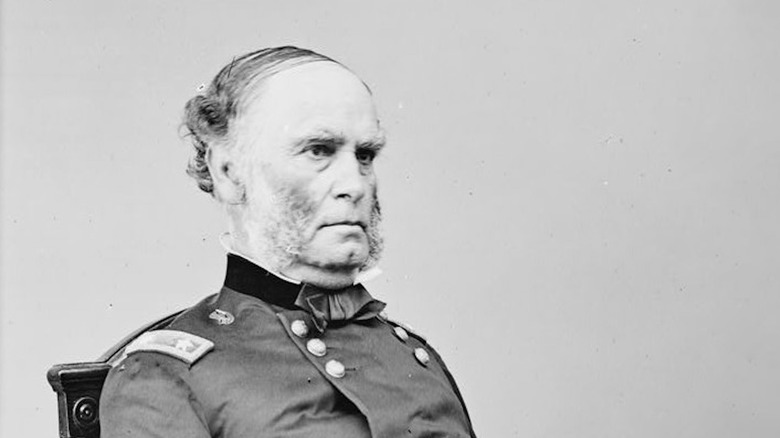

John E. Wool

The New York-born-and-raised General John E. Wool was 77 years old when the Civil War began, making him the oldest officer to serve in the military during the war. This also wasn't his first experience with war. As described by Laurence M. Hauptman in a 2003 issue of Kent State University's "Civil War History," Wool was a veteran of the War of 1812 and the Mexican-American War. By the time the Civil War began, he was second in terms of seniority in the entire Union army, behind only General Winfield Scott.

During the first year of the war, he was in New York City where he worked to organize soldiers and broker war contracts, according to the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum. He was promoted from Brigadier General to Major General after assisting with the reinforcement of Fort Monroe against Confederate forces in Virginia (per NPS). Despite his image within the military, his reputation among the public suffered after the New York City Draft Riots of 1863 because he was unable to successfully put an end to them. A deeper look at his earlier career shows he was also involved in the forced relocation of Native Americans both in the South and the Pacific Northwest (per Oregon Encyclopedia).

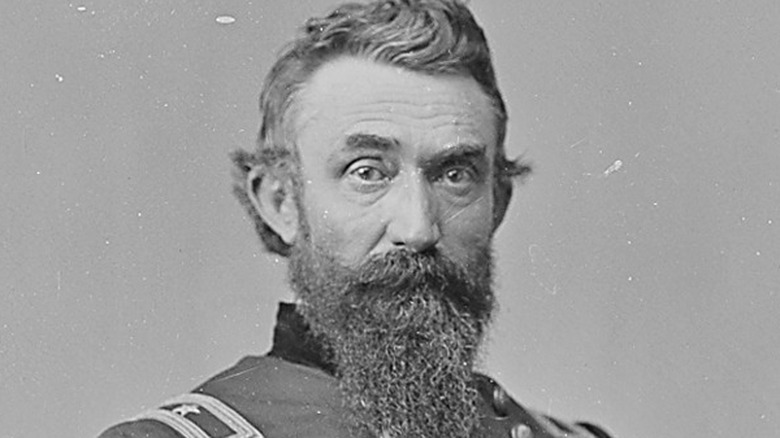

Nathan Kimball

Born on November 22, 1822, in Indiana, Nathan Kimball graduated from DePauw University in 1841 before he went on to study medicine at the University of Louisville and became a practicing physician (per American Battlefield Trust). He then gained military experience as a captain of the volunteer forces in Indiana during the Mexican-American War. According to the Indiana Historical Society, when war broke out in 1861, he was appointed to the rank of colonel overseeing the 14th Indiana Volunteer Regiment in Virginia, before being promoted to brigadier general the following year. As a brigadier general, he oversaw his brigade's involvement in the bloody Battle of Antietam and the Battle of Fredericksburg where he received a wound that took him out of commission for months (per NPS).

After Kimball's recovery, he was involved in the siege of Vicksburg where he led a division and reported directly to General Ulysses S. Grant. Afterward, he was part of the Atlanta campaign under General William Tecumseh Sherman but then had to return to Indiana where he dealt with a secret insurrectionist group called the Knights of the Golden Circle. Britannica describes the Knights of the Golden Circle as a group that was against war policies created by Abraham Lincoln and worked to sabotage the draft and encouraged desertion. After successfully dealing with that, Kimball returned to lead soldiers in the campaigns of Franklin and Nashville before being promoted to major general.

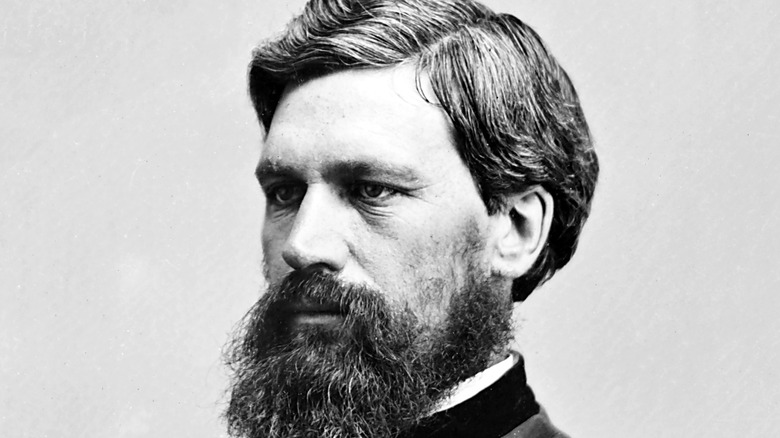

Oliver O. Howard

Oliver Otis Howard is a name that many may not know in full, but it is certainly a name they'll recognize for other reasons: He's the namesake for Howard University in Washington, D.C. His story began when he was born in Leeds, Maine in November 1830 (per Britannica). He received a college education from Bowdoin College before entering West Point. Upon graduation, he joined the war against the nation of Florida Seminoles in the Third Seminole War, which according to the Florida Department of State, reduced the Native population to only 200.

Like many Civil War generals, his attitude towards Native Americans was troubling. According to Smithsonian, he believed that forcibly relocating Native Americans to reservations was actually lending them a hand. That is, he still believed that they needed to be led to assimilation — becoming farmers on a "path toward citizenship" — rather than allowing them to retain their own land and culture.

He made a name for himself leading a brigade at the Battle of Bull Run (per American Battlefield Trust) and was promoted to brigadier general after being wounded at the Battle of Fair Oaks, which resulted in the loss of his right arm. This wouldn't slow him down too much. He still led the Battle of Chancellorsville, was involved in the campaigns in Tennessee and Atlanta, walked with General William T. Sherman during his infamous March to the Sea, and ended the war fighting in the campaign for the Carolinas (per Britannica).

Edward Canby

Edward Richard Sprigg Canby, born on November 9, 1817, in Kentucky, began his military career at the United States Military Academy in 1835 (per University of Chicago). After graduating in 1839, he served as a Second Lieutenant in the second of Florida's Seminole Wars which, as explained by Britannica, occurred when the Seminole, using guerilla warfare to fight off the American oppressors, held their grand on their native land when government forces tried to forcibly relocate them west of the Mississippi River.

Canby worked his way up the ranks over the following decades, gaining military experience out west. When the Civil War broke out, he was promoted to the rank of colonel and, according to the American Battlefield Trust, saw his first combat of the war in the Battle of Valverde in New Mexico. As described by History, this was the first important Civil War battle out west and was due to Confederates wanting the land and resources. This battle was followed by the Battle of Glorieta Pass which resulted in a retreat of Confederate forces and led to Canby's promotion to brigadier general and then major general. In April 1865, he commanded the forces that captured Mobile, Alabama (per NPS). After the war, Canby would be important during the Reconstruction era in the south (per Encyclopedia of the Reconstruction Era). He would later be involved in the Modoc Wars in Oregon, where he became one of the "only generals ever killed by Native Americans," according to History.

Abner Doubleday

Legend has it that General Abner Doubleday invented the game of baseball. While it's now known that this is not true, as noted by Britannica, the New York-born Doubleday still had quite a few accomplishments throughout his life. After graduating from the United States Military Academy in 1842, he eventually found himself at Fort Sumter, South Carolina on that fateful day that the first shots of the Civil War were fired. In fact, explained History, it was Doubleday who ordered the first shots fired by Northern soldiers after the Confederate attack began. According to NPS, when asked by Captain Truman Seymour what was happening, Doubleday replied, "[T]here is a trifling difference of opinion between us and our neighbors opposite, and we are trying to settle it."

Within a year, he was promoted to brigadier general and he would command soldiers in the Second Battle of Bull Run and the Battles of South Mountain, Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Gettysburg. Near the end of the war, he would also be instrumental in the protection of Washington, D.C. when it was at risk from Confederate invasion. Today, while it may be known he didn't invent the game of baseball, the National Baseball Hall of Fame & Museum was built in Cooperstown, New York in his honor and West Point's Doubleday Field also bears his name (per Minor League Baseball).

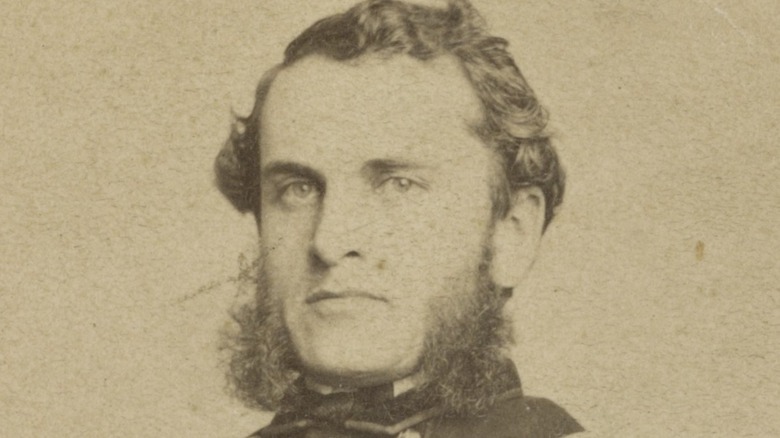

Strong Vincent

Strong Vincent was a 26-year-old lawyer with no formal military training living in Erie, Pennsylvania when the Civil War broke out (per Erie County Historical Society). He promptly married his college sweetheart and then volunteered with the 83rd Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry under Colonel John McLane. Despite his lack of experience, he quickly climbed the ranks to second in command. When McLane was killed during the Battle of Gaines' Mill in 1862, Vincent took over to lead in the midst of the battle.

Over the following year, he led his 1,300 men in the Battles of Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville before leading them to Gettysburg, reportedly telling his men (per Explore PA History), "What death more glorious can any man desire than to die on the soil of old Pennsylvania for that flag." As explained by the Erie-Times News, while he is not often remembered outside of Civil War history buffs, he was the "savior and hero of Little Round Top" on July 2, 1863, when he led his men there and demanded that they "don't give an inch." During the battle, he was hit by a thick bullet and would die a few days later. Before his death, Major General George G. Meade recommended that Vincent be promoted to the rank of brigadier general, but it is unlikely that Vincent knew this before his death.

David M. Gregg

Described by author David J. Eicher as the "unsung hero" of Gettysburg, David M. Gregg was a Pennsylvania-born West Point graduate who was stationed in California when the Civil War began. According to the American Battlefield Trust, he returned east to oversee cavalry units throughout 1862 before being promoted to brigadier general. Over the following months, Gregg's soldiers clashed repeatedly with Confederate General J.E.B. Stuart leading up to the Battle of Gettysburg.

It was on the final day of this fateful battle that Gregg's soldiers beat back Stuart's cavalry as they attempted to crush the Union forces from the rear (per Smithsonian). As explained by Berks History Center, Gregg was able to do so with fewer soldiers and much less preparation than others in the battle. Eicher argues in the biography, "Unsung Hero of Gettysburg: The Story of Union General David McMurtrie," that it was his dislike of publicity as well as his leanings towards Democratic Party politics that hurt his ability to move up the ranks and gain the recognition that some argue he deserved.

August Willich

August Willich was perhaps an unlikely general in the Union military. Historian David T. Dixon referred to him as the "radical warrior." He had been an officer in the Prussian military before immigrating to the United States after facing exile, according to Oxford Reference, as well as an early advocate for communism. As described by Kent State University though, he organized and led Indiana's German 32nd regiment brilliantly through battles in Kentucky, Tennessee, and Georgia. While as a regiment they often faced biases, which manifested through late payments, shoddy weapons, and lack of promotions, they were an effective group of soldiers (per Johns Hopkins University).

As described by Cincinnati Magazine, Willich's soldiers were known for being "hard-fighting" and "disciplined." During the Battle of Stones River in Tennessee, Union forces barely won, but Willich's horse was killed and he was captured and imprisoned by the Confederates. Once captured, he continued to plan and strategize over the following months before being released. Before and during the war, he was strongly opposed to both slavery and racism (per Oxford Academic). After the war, he went on to study philosophy. In his obituary in The New York Times following his 1878 death, editors described him as "the ablest and bravest officer of German descent."

Horatio Wright

Horatio Wright, born March 6, 1820, was a Connecticut native who graduated from West Point and entered the military as an engineer. As described by Connecticut History, he stayed at West Point where he taught engineering and French before being assigned a decade-long stint in Florida to work on fortifying the coastline. When the Civil War erupted, Wright put his engineering knowledge to use and helped fortify defenses around Washington, D.C. before soon joining the battlefield at the First Battle of Bull Run (per NPS). From there, he worked his way up the ranks, nearly attaining status as major general but having the appointment rejected by Congress the first go around. He remained a brigadier general until it was later approved in 1864.

Over the course of the war, he commanded his division through the Battles of the Wilderness, Gettysburg, Cold Harbor, Fort Stevens, Cedar Creek, and Sayler's Creek. After the war ended, he spent a year as the military governor of Texas (per Arlington National Cemetery). He then continued his career in the service and helped with the construction of both the Brooklyn Bridge and the Washington Monument (per American Battlefield Trust).

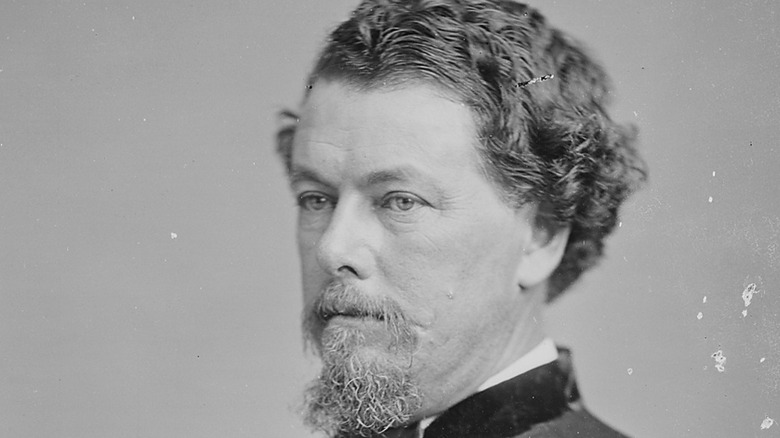

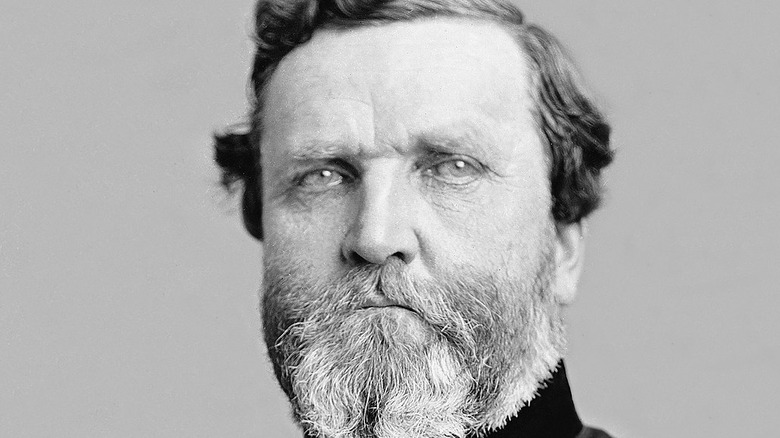

David Hunter

David Hunter, born in Troy, New York on July 21, 1802, had been friendly with Abraham Lincoln leading up to the Civil War, with the two men sending private letters back and forth expressing their abolitionist views towards slavery (per American Battlefield Trust). When the Civil War erupted, Hunter was initially made a colonel to oversee the 3rd United States Cavalry Regiment, but within a few days, his friendship with Lincoln led to his appointment as a brigadier general. According to the National Park Service, that July, during the First Battle of Bull Run, he received wounds to his face and neck but survived, and two months later he received a promotion to major general.

If Hunter is remembered for anything during the Civil War, it is likely an event that happened in 1862. While commanding troops in the south, Hunter controversially made the proclamation that the enslaved people of Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina were now free (per Britannica). President Lincoln, who was worried about what effects such an order could have on the border states, immediately rescinded the order. Despite this, his work continued and he put together the North's first Black regiment, leading to Confederate President Jefferson Davis stating that he was a "felon to be executed if captured."

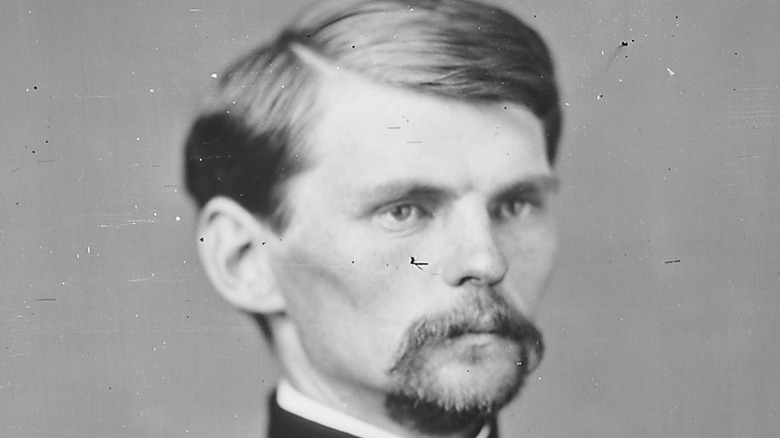

Emory Upton

While General Emory Upton may not be a household name like Grant or Sherman, his influence on military tactics and military history cannot possibly be understated, especially with the posthumous 1904 publication of "The Military Policy of the United States." Yet, long before this, Upton was a New Yorker who attended Oberlin College before attending West Point and a "radical thinker" who once ended up in a duel over someone criticizing his acceptance of interracial dating. As described in "The Life and Letters of Emory Upton," he was a staunch abolitionist, although he didn't talk openly about it. "He again and again felt sure that war would come," one friend recalled," [and] that he would be just ready for it."

When war came, Upton was fresh out of West Point and joined the First Battle of Bull Run as a lieutenant in the 5th Artillery Regiment (per American Battlefield Trust). He proved to be a "noted military strategist," according to Encyclopedia Virginia, and after demonstrating impressive and innovative tactics to storm the Confederate forces, General Ulysses S. Grant promoted him to brigadier general. Following the war, he was widely considered one of the more important strategists in the United States and was influential in terms of his ideas of military reform (per "Military Medicine"). Sadly, he died by suicide on March 15, 1881, at 41 years old.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

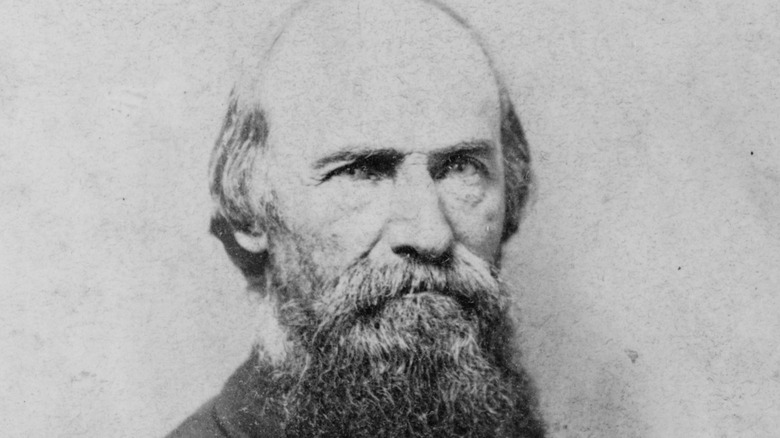

Samuel Curtis

Samuel Ryan Curtis was an 1831 graduate of the United States Military Academy, a civil engineer, and an elected official in Congress all before the Civil War began. When the war commenced, Curtis resigned from Congress and was promoted to brigadier general (per American Battlefield Trust). He is perhaps best known for his victory at the Battle of Pea Ridge. As described by Britannica, in 1862, Curtis led his 11,000 Union soldiers into battle in Arkansas against 16,000 Confederates. After almost getting taken out Curtis and his troops turned the tides of the battle and forced the Confederates into a retreat.

Throughout the rest of the war, Curtis has various commands before finally ending the war overseeing the Department of the Northwest, according to the Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Following the war, he was appointed as a peace commissioner to work on peace treaties with Native American nations as well as becoming a commissioner to report on the Union Pacific Railroad. He died on Christmas in 1866 at the age of 61 (per House of Representatives). As explained by the State Historical Society of Missouri, despite being relatively unknown, many historians consider him both "capable and underrated" as a military general.

George H. Thomas

Although he is described by Smithsonian as "stubborn" but "deliberate" and one of the "Union's most brilliant strategists," General George Thomas isn't a household name. His history was complicated: He grew up in Virginia in a family that enslaved people and even become close friends with future Confederate General Robert E. Lee (per NPS). Yet, when the Civil War began and lines were drawn, the West Point graduate stayed loyal to the Union (along with his West Point roommate William Tecumseh Sherman), resulting in disownment from his own family. As explained by Britannica, as a brigadier general, he led forces in Kentucky against Confederate soldiers at Mill Springs, resulting in one of the first Union victories in the west. He then led forces in the Battles of Nashville and Stone's River as well as the campaigns of Chattanooga and Atlanta (with his old roommate Sherman).

According to Encyclopedia Virginia, despite having enslaved people himself before the war, his experiences in the Civil War led to his views changing. He supported the expansion of civil rights during Reconstruction and worked to defend Black people from the Ku Klux Klan in the years following. After his death in 1870 at age 53, his old friend Sherman described him as one of the great heroes of the Civil War that deserved monuments to be erected in his honor (per American Battlefield Trust).