The Scariest Moments Ever During Spacewalks

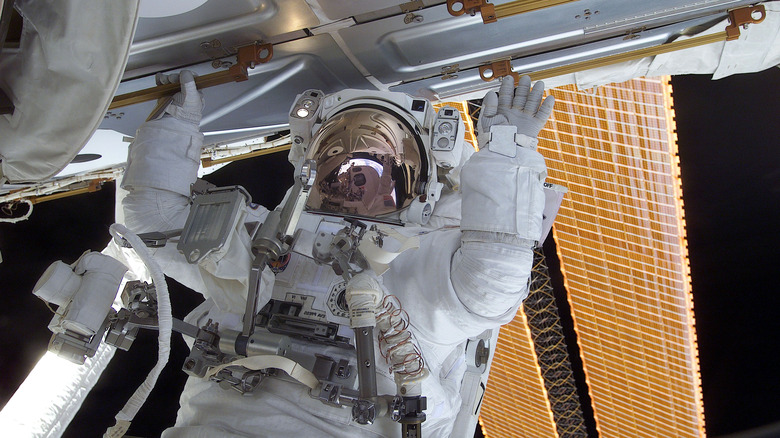

Earth-bound folk can only imagine what it feels like to go on a spacewalk — or extravehicular activity (EVA) if we're getting technical (via Smithsonian Magazine). Floating in the void, looking at the Earth below, it must feel like you're on top of the world ... literally. Still, while some astronauts feel like they are flying during this essential task — used for ship repairs, experiments, and the like — others have felt like they were dying, or at least they came pretty close. Thankfully, not a single death — out of the 30 astronauts and cosmonaut deaths that have occurred throughout the spacefaring age — happened on, or was caused by, an EVA (via Astronomy).

According to NASA records, over 250 spacewalks have taken place at the International Space Station – which floats just about 250 miles above Earth's atmosphere (via NASA). Spacewalks are now considered a routine procedure — over 1,100 hours have been committed so far. Thanks to how well-trained astronauts are — with a total of six years of higher education, followed by two years of professional experience (via Indeed), and two years in NASA basic training, which, according to NASA, the training includes subjects of survival, speech, language, science, medical procedures, and more – there have been no deadly incidents.

Still, accidents do happen. And when you are floating alone in space, those accidents are terrifying.

Leonov's emergency within minutes

The 30-year-old Cosmonaut Alexey (also spelled Alexei) Leonov completed the very first spacewalk on March 18, 1965 (via Phys.org). Russians had beaten America in the race to space(walking), and Leonov was tasked with recording the great achievement, according to Time. The plan was to attach one camera to the outside of the airlock, and one to his suit. But right as the show was about to begin, disaster struck — cutting Leonov's spacewalk down to 12 minutes.

Modern EVAs can last over six hours, but if Leonov had not retreated when he did, he might not have been able to return at all. Upon entering the vacuum of space, his suit began to inflate rapidly. At that point, it's probably safe to say getting the planned selfie footage was the last thing on his mind. While tethered at about 16 feet (modern tethers are 85 feet, according to the BBC), his suit quickly became so wide that he wasn't going to be able to get back in his spaceship. Staying calm through the panic, he did not alert ground control; he wanted to handle the emergency himself, despite his body temperature shooting up so fast that he was in danger of heatstroke. He slowly released oxygen from his suit, and although that solution put him in danger of suffocation and rapid depressurization, he managed to shrink it just enough to fit.

Sadly, Leonov's troubles didn't end there. Upon returning home to Earth, a mistake caused his ship to crashland in the thick Russian wilderness, blanketed with snow and infested with wolves and bears. Fortunately, he and the crew were eventually rescued.

Cernan's boiling point

Eugene Cernan became the world's third spacewalker on the "cursed" Gemini X expedition (via National Air and Space Museum). After members of the original crew were killed in a T-38 accident, Cernan and Thomas Stafford were promoted from backup. Takeoff was attempted several times, but technical errors kept causing delays, so they would not see space for five months.

Finally in space on June 3, 1966, they completed their various assigned tasks, but Stafford waited until the final day to attempt the spacewalk. Considering the experience he was about to have, this was a good call, since returning home as soon as possible must have seemed like a blessing. During the EVA, Cernan needed to wear a jetpack to fly about the ship. For protection from the jet pack's heat, the spacesuit he wore had pants that were essentially made of metal. But the protection that was supposed to protect him from heat ... made him overheat. He said the suit had "all the flexibility of a rusty suit of armor" and moving around in it was torturous. Cernan could have died from overexertion, dehydration, and extreme weight loss; he lost 13 pounds from the spacewalk, all of it water weight. He was in pain and blind due to sweat fogging up his helmet. The crew pulled him back in and hosed him down.

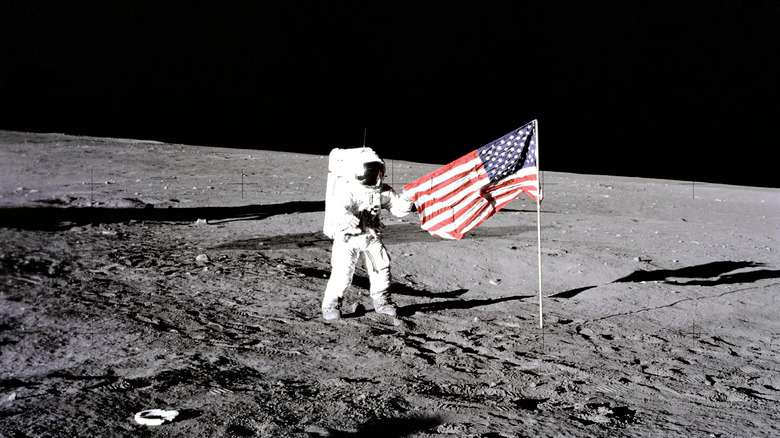

Underwater EVA tests quickly proved that given nothing to hold onto, astronauts would overexert themselves. Future designs — including those used on Apollo 11 — were required to implement cooling components. Cernan went on to become one of the few astronauts to walk on the moon.

Floating away? Not today.

The tethers attached to astronauts' spacesuits are often one of the only things preventing them from floating off into the depths of space (via BBC). Without them, incidents that happened in 1973 (via NASA) and 1977 (via AP News), respectively, could have been a lot more devastating.

The 1973 incident propelled two astronauts into space during a spacewalk. Peter Conrad and Joe Kerwin were repairing a solar wing that did not deploy when the ship took off. When they were finally able to dislodge the stuck solar wing, the force propelled them into open space. Fortunately, thanks to their tethers, they could be pulled to safety.

The second incident involved cosmonauts Yuri Romanenko and Georgi Grechko in the airlock chamber of the Salyut 6 space station. Romanenko, who was prepping for an EVA, nearly floated out of the airlock chamber, untethered. Thankfully, Grechko moved quickly and pulled him back in by his unfastened safety line. To circumvent potential disasters, astronauts work in buddy systems of at least two, so one astronaut can exit the airlock first — tethering them to the outside of the ship — while the last one out disconnects from the airlock. Regardless of how unlikely "having a bad day is" (astronaut code for the potential perils of the job, as per Smithsonian Magazine), it's still the biggest fear of most astronauts, including Chris Hadfield. He once wrote, "my number one concern ... is to avoid floating off into space."

Testing for safety, is not safe

Astronauts of the past were not as protected as those exploring space today. In fact, while tethers used to be the only tool astronauts had at their disposal to prevent perilous death, modern astronauts have jetpacks to help them fly through the sky, or at least back to the ship if they happen to float off (via BBC). "[We wear] a jetpack, and you can pull down this handle and a joystick comes out of a little hidden drawer and pops out in front of you," astronaut Chris Hadfield told BBC. "You activate the joystick, and you can fly your jetpack, and grab back onto the space station."

And while jetpacks were a huge step for astronaut safety, the first to test them wasn't in the safest situation, according to National Geographic. The first astronaut to float freely in space was Bruce McCandless on February 7, 1984, as seen in the famous photo of him hundreds of miles above Earth. If something had gone wrong, he would have floated off into space, with his helpless crew unable to pull him back. According to KUNC (NPR for Northern Colorado), McCandless once said, "[It] may well have been one small step for Neil, but it's a heck of a big leap for me!"

A hole-in-glove

Even in a 14-layer spacesuit that is supposed to be rip-resistant, things can go wrong and accidents can happen, especially when working with sharp objects and tools (via NASA). In 2007, a spacewalk Rick Mastracchio and Clay Anderson were on took an unexpected turn when Mastracchio discovered a hole in the top layer of his left glove, right on the inseam of his thumb, as per BBC. The discovery prompted an immediate shutdown of the EVA, according to Reuters; even though it was a little hole, it could have quickly become a big emergency.

The spacewalk was scheduled to last six and a half hours, but it was cut short at four (via Space.com). Albeit disappointing, if the duo had not stopped working, Mastracchio could have been exposed to the vacuum of space, where the body can nearly double in size. He could have also suffocated and been knocked unconscious, floating aimlessly in the depths of space. The scariest part of it all is he does not know how it happened. "I can see the surface under the Vectran material," Mastracchio told Houston, according to BBC. "The gloves were good. I don't know where this hole came from," he said (via Reuters).

Under pressure

The Skylab — America's first space station — was launched on May 14, 1973 (via NASA). From the very start, it was propelled into serious problems. Upon launch, the station's micrometeoroid shield deployed too soon, and under the force of flight, it ripped off the ship's thermal protection. In addition to this, the ship's two main solar arrays did not deploy. Because of these two events, the station was flying underpowered, which led to overheating at temperatures over 130 degrees Fahrenheit. The intense heat could have also potentially destroyed all the food onboard, as well as released toxic gasses into the ship.

NASA planned to send astronauts up in the Skylab 2 Command Module, armed with a massive reflective parasol — made of aluminum, nylon, and Mylar — to be used as an artificial skin for the station. Commander Charles "Pete" Conrad, Pilot Paul J. Weitz, and Science Pilot Joseph P. Kerwin were up for the task. Upon doing a fly-around of the ship, they realized the workshop's golden underbelly was exposed, one solar array was missing and another was blocked by debris. With Kerwin holding down his legs, Weitz conducted a stand-up EVA for 40 minutes but was unsuccessful. After a 22-hour day, the crew docked at the station. The next morning, under extreme pressure and heat, they were able to install the parasol. The temperature of the ship reached a comfortable level within three days.

Beamer gets sprayed

Flying through space with nothing but a spacesuit and your own thoughts is scary enough — but imagine doing it covered in toxic chemicals (via The New York Times). Well, during a 2001 spacewalk, while Robert "Beamer" Curbeam was 'beaming' through space about the International Space Station, that is exactly what happened. Ammonia is a smelly chemical used in the space station's cooling components, due to its extremely low freezing point. While Curbeam was working on the station, a cooling line leaked and sprayed his entire space suit with the substance. It's reported that there were inch-long ice crystals coating his spacesuit and helmet.

Curbeam questioned himself. He was told during training that leaks of this sort, from a male quick-disconnect connector, were so unlikely they were nearly impossible. Yet here it was happening. Curbeam once said that during the chaos, he thought to himself, "Oh, my gosh — what did I do wrong?" Truly though, Curbeam did nothing wrong. Regardless, he still had to deal with it, and reportedly struggled so hard, that he bent the metal foot holding he was on. In an interview, Curbeam noted that "people die in industrial accidents with anhydrous ammonia."

He ended up entering the ship back to safety, but only after mission control commanded he wait outside for an entire orbit around Earth — about 90 to 93 minutes, according to NASA — until the remaining ammonia flaked off. If he had come in too soon, the entire ship could have been exposed.

At war with the suit

While their 280-pound spacesuits are weightless in space, astronauts still struggle (via NASA). "Every move you make ... you have to push against that amount of inflated resistance. You come in from a spacewalk absolutely physically whipped, and often you've worn through the skin somewhere — you're bleeding — just because the suit is a misery to work in," astronaut Chris Hadfield once said, according to BBC. "You use twice as much effort basically doing anything on a spacewalk." And with overexertion comes sweat, spit, and sometimes tears — which don't fall in zero gravity, as per Smithsonian Magazine. Until the moisture evaporates, it can be very bothersome, and even blinding. If there is a lot of it, evaporation is unlikely so it kind of just floats around in there; possibly covering the eyes, nose, and mouth, and even fogging up the spacesuit's visor (via NBC).

But sometimes, suit malfunctions can cause fluids to leak into the helmet, which is what happened to Terry Virts in 2015. He and astronaut Barry Wilmore were working on the space station's robotic arm for almost seven hours, and upon finishing, Virts saw a blob of water in his helmet (via CNN). He knew it wasn't drinking water, according to Space.com. "It's not drink bag water," Virts told Mission Control. "If you taste the water, it has a chemical taste ... it's some type of technical water." Virts' suit had previously experienced subliminal water carryover, which happens when suits re-pressurize. Upon inspection, fellow astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti described the helmet as "wet and cold," and said its absorbent pad was damp. It has been reported that 15 milliliters of water leaked from the spacesuit's cooling system.

Drowning in space

Even small droplets of water inside a helmet can temporarily blind an astronaut — so you could imagine what 1.5 quarts could do (via Smithsonian Magazine). In 2013, Luca Parmitano conducted two EVAs with NASA legend Chris Cassidy, and the first one ran very smoothly (via BBC). During the second EVA on July 16, Parmitano realized he felt water on the back of his neck, right as he was gauging a crevice on the outside of the station for maintenance accessibility. At first, both he and Cassidy disregarded it as sweat, but the duo was still recalled back to the station. They had to go separate ways because they were working in different areas, and during that brief period when Parmitano was alone — disaster struck.

For a brief moment, Parmitano had to flip upside down, causing a ton of water to rush to his helmet. "It completely covered my eyes and my nose. It was really hard to see. I couldn't hear anything. It was really hard to communicate," said Parmitano. "I couldn't breathe through my nose — I felt isolated and when I tried to tell ground that I was having trouble finding my way, they couldn't hear me, and I couldn't hear them either." Parmitano eventually pulled himself back through the airlock headfirst; his crewmates saved him and found nearly a quart and a half of water inside his helmet. He said he "was just waiting for the [it] to end, taking it one second at a time." The Veteran EVA chief on the International Space Station, Joe Tanner, said: "[he] had every right to be fearful for his life."

Danger: High Voltage

In the summer of 2022, a "shocking" development caused a spacewalk — that was scheduled to be seven hours long — to be cut short to just a few hours (via CNN). Russian cosmonauts Oleg Artemyev and Denis Matveev were tasked with installing two cameras on a robotic arm outside the Russian-controlled portion of the International Space Station. Trouble came when mission control realized that Artemyev was experiencing issues with the battery pack powering his spacesuit, but he would not return right away to connect it to a power source. "Drop everything and start going back right away," Mission Control reportedly demanded of Artemyev, after several warnings to head back.

The issues with the battery pack were causing "voltage fluctuations," so while Artemyev was not in any serious immediate danger, he could have been. Without power, he could have lost communication with his partner Matveev and Mission Control, so if an emergency were to happen — he would be on his own. This EVA was Artemyev's seventh during his cosmonaut career.

A mandatory pause

While EVAs have certainly come far from the first in 1965, they are still not 100% safe — as made evident by incidents that occurred in the summer of 2022, per CNN. Nor was that even the only incident that year: On March 23, 2022, the sweat of one astronaut caused a temporary shutdown of all non-essential EVAs from the International Space Station (via Space.com).

European Space Agency astronauts Matthias Maurer and Raja Chari were tasked with prepping the space station for new iROSA solar arrays. After nearly seven hours of work, Maurer noticed moisture inside his helmet.

Triggered by fear of recent water-related disasters, NASA prompted an immediate hold on all non-essential EVAs, which lasted seven months. By October 2022, NASA discovered the cause of the moisture in Maurer's helmet wasn't a leak somewhere in the spacesuit, but a build-up of condensation from overexertion. NASA vowed to change its procedures to circumvent any watery accidents. "Based on the findings, the team has updated operational procedures and developed new mitigation hardware to minimize scenarios where integrated performance results in water accumulation while absorbing any water that does appear," NASA announced. "These measures will help contain any liquid in the helmet to continue to keep crew safe." Still, considering a few beads of sweat triggered the shutdown of one of the International Space Station's most important operations, it's safe to say they're still pretty risky.