Olympics: The Brief History Of Art Competitions At The Games

The Olympics are possibly the most iconic sporting event in the world. With recent Games featuring around 11,000 competitors from 205 countries (via Britannica), the Olympics draw millions of global viewers — not to mention the thousands of spectators who buy tickets to witness the Games in person.

In fact, the Olympics are such a big deal that countries vie for the chance to host them, covering the extensive costs of massive stadiums and athletic quarters in order to earn the notoriety — and economic boost — that hosting such a major event brings. With world records regularly broken at Olympic competitions (via The New York Times), truly, this sporting event determines which athletes are the best of the best.

At the very beginning, the Olympics used to find the best artists, too. In the early decades of the 20th century, there was an art component to the Olympics, with medals handed out for skills from sculpture to town planning. In other words, it wasn't just brawny shot-putters or lithe runners who could cinch an Olympic title. Anyone could do it, if they were talented enough.

The first Olympic Games

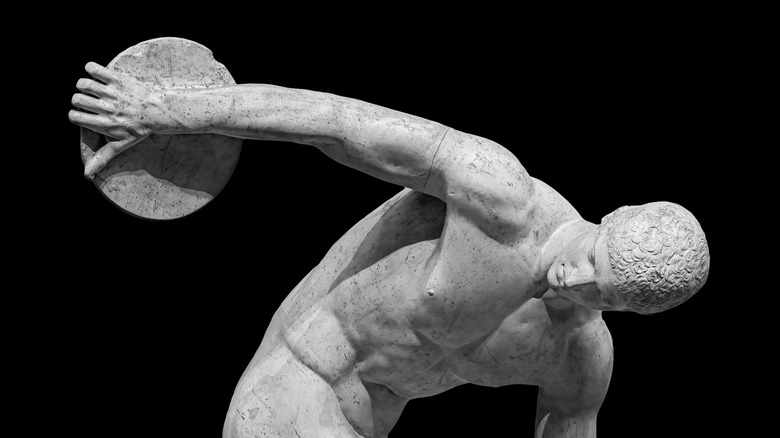

Though the modern Olympic Games have only been around for a little over a century, the earliest form of the competition dates back to the time of the ancient Greeks, some three millennia ago (via the official Olympics website). First held in or before 776 B.C., the Games were designed to celebrate Zeus, the leader of the Greek gods, according to History. The earliest competitions included the stade, a 192-meter sprint. In many ways similar to the modern 200-meter sprint, this race was first won by a lowly cook (via History).

Hosted in Olympia, the competitions were held once every four summers, with the period between games known as an Olympiad, reports the Olympics website. Over time, people in ancient Greek society decided to use Olympiads to count long stretches of time instead of single years — a testament to the event's popularity, according to History. However, the Games eventually fizzled out, with the last ones being hosted by the end of the fourth century A.D. before they were officially outlawed by a Christian emperor on the grounds that they constituted a "pagan" festival.

The founding of the modern Olympic Games

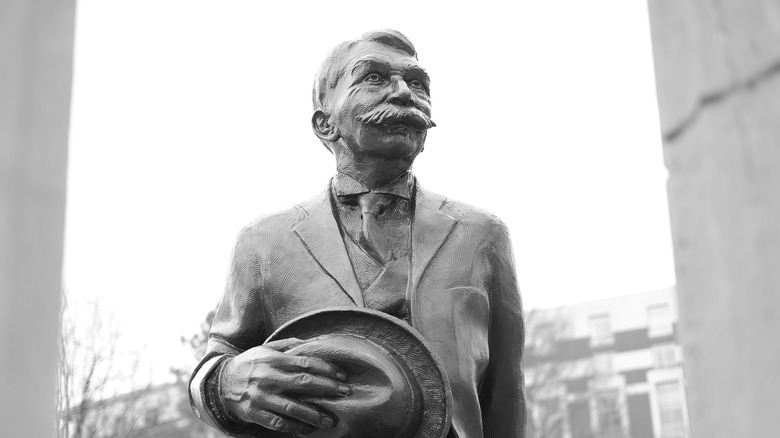

The Olympic Games came back on the international stage in 1896 after a French man named Baron Pierre de Coubertin (his statue pictured above) decided he wanted to bring them back. Coubertin got it in his mind to revive the Games after going to Olympia himself, according to History. Coubertin first brought up the idea of restarting the tradition in the 1890s during a world's fair (via Britannica).

Initially, Coubertin's colleagues were skeptical about the concept. He managed to persuade them to give it a shot, and the first modern event was scheduled for 1896. Coubertin was declared the International Olympic Committee (IOC) president, a position he would retain for the next 29 years before he finally retired in 1925, per Britannica.

The first modern Olympics were a big success. Held in Athens to honor the Greek origins of the competition, the races were viewed by a whopping 60,000 spectators, per History. Among the competitions held was the first Olympic marathon, a modern invention designed to emulate a run of similar length thought to have been made by a single Greek soldier more than 2,500 years ago. However, despite the apparent evidence in support of Coubertin's genius, it took organizers a while to get on board with his other vision for the Games: that they include an art component.

How art came into play

Despite the success of the 1896 Olympics, Pierre Coubertin wasn't satisfied with the event. In addition to athletic competitions, he wanted to add arts categories, so that people of different and varied skills could be recognized. After all, to the ancient Greeks, the ideal man wasn't just strong; he was smart (per the Olympics website). Accordingly, Coubertin thought the Olympics should reward creativity and intelligence in addition to athletic skill.

In a pitch for adding art to the Olympics in 1904, Coubertin is quoted as saying (via the Olympics website), "The time has come to take the next step, and to restore the Olympiad to its original beauty. In the high times of Olympia, the fine arts were combined harmoniously with the Olympic Games to create their glory. This is to become reality once again."

In fact, as Coubertin saw it, adding art to the Olympics was a key way to identify it as superior to existing athletic competitions (via The Washington Post). "There is only one difference between our Olympiads and plain sporting championships, and it is precisely the contests of art as they existed in the Olympiads of Ancient Greece, where sport exhibitions walked in equality with artistic exhibitions," he once said, per Smithsonian Magazine. In the end, Coubertin managed to persuade his peers, and in 1912, art categories became part of the competition roster for the Stockholm Games.

Types of Olympic art competitions

Not just any art could be submitted to the Olympic competitions. It had to meet a few key requirements, including that all art pieces be related to athletics (via the Olympics website). There was also a rule saying that art could not have been previously exhibited — so Claude Monet, for example, couldn't just pull a painting from his most recent sold-out exhibition to submit for the Games.

In the first Olympics art competition, 33 competitors entered in five different categories: architecture, sculpture, literature, music, and painting (via Smithsonian Magazine). In early Olympic Games, categories stayed relatively broad, with literature, for example, comprising a variety of forms from epics to plays (per The Daily Sabah). However, after several years, organizers decided to implement subcategories, which included orchestral and instrumental music and solo and chorus singing for music, for example, and statues, reliefs, medals, plaques, and medallions for sculpture (via the Olympics website).

Paris and LA made art competitions big

The Olympic Games were a success right off the bat, but it was the 1924 Paris Olympics that marked the moment when they became an international phenomenon, both for sports and for art, according to History. That year, 193 artists submitted their pieces to the competition, according to the Olympics website, or more than five times as many people who submitted their works to the first games.

Part of the way Paris attracted so many applicants was by sharing the names of all the famous people who would be judging the competition, according to The Washington Post. Among their ranks was Igor Stravinsky, a prominent composer, who judged in the music category. Artists may have initially been excited to have their work judged by Stravinsky, but that excitement probably faded after the public results of the panels were released: Stravinsky was ultimately disappointed by the submitted works and didn't award any prizes in his category, according to The New York Times.

Later, the Los Angeles Olympics in 1932 highlighted Olympic art profiles again with over 1,100 entrants whose work was viewed by around 400,000 spectators, according to The Washington Post.

The winningest countries

Some of the biggest winners in the art categories probably won't surprise you. France, for instance, which is known for its great artists, is tied for the second-most Olympic art medals won in the competition, with 14 total, including five golds (per Mutual Art). It's tied with Italy, also known for its art, which likewise won 14 total medals, five of which were gold.

At the bottom of the list, Greece, Norway, and Monaco only won a single art medal apiece. For its part, the United States managed to grab nine medals, including four gold and five silver.

But who's the winningest country for Olympic art? Surprisingly enough, it's Germany. The country took home a tidy 24 of 151 total Olympic art medals — nearly one-sixth of everything handed out, according to Mutual Art. What accounts for the huge number? There was surely skill involved, and it's worth noting that Germany has a pretty large population relative to many other European countries. But another big factor might have been at play: bias.

Judges may have been biased

Olympics sports competitions are usually hard to judge incorrectly, considering that many of them — including swimming and track and field — are solely based on speed. Others, like gymnastics, rely on eagle-eyed judges who are willing to make swift calls. But even in these situations, judges usually have detailed guidelines for awarding and deducting points.

On the other hand, though art judges can attempt to be impartial with their rulings, there is an element of subjectivity in play (via Mutual Art), which can raise the question of whether judges were biased by the nationalities of various competitors. In fact, this is part of what made Pierre Coubertin's peers reluctant to institute art competitions in the first place (per The New York Times).

To some extent, this bias does seem to have played out in practice. For instance, in 1932 in Los Angeles, a full 80% of the judges — 24 out of 30 — were American, and many of the award winners were, too (via The Atlantic). Likewise, in Berlin in 1936, 29 of 41 total judges were German, which may be part of the reason Germans won more than half of all gold art medals that year, according to The Atlantic. "The fact that German entrants won more art medals than any other country at the 1936 Berlin Games, and American medalists dominated the art competitions at the 1932 Los Angeles Games speaks of the credibility of the judging," wrote Christine Bednarz for Mutual Art.

The most famous winners

The Olympics were designed to be an amateur's game — and rich and famous artists didn't want to stoop so low as to submit themselves before a panel of judges — which means the biggest artists of the 20th century mostly didn't participate in the Olympics, according to Smithsonian Magazine.

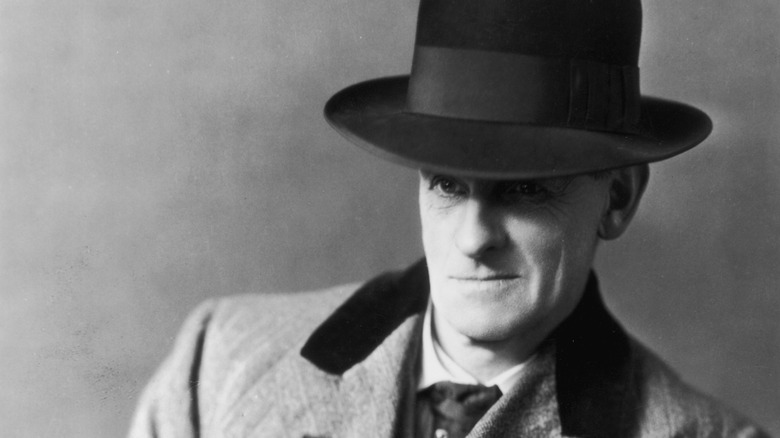

But some winners do stand out. First, IOC founder Pierre Coubertin won a medal in 1912, the inaugural year for Olympic art competitions. Coubertin submitted a poem called "Ode to Sport" in the literature category, ultimately snatching up the gold. He did so using a fake name, presumably to ensure his influence didn't bias results (via Mutual Art). Jack Butler Yeats (pictured) also won an artistic Olympic medal. Yeats, a renowned painter, won a silver medal for his oil painting of a swimming race, according to The Irish Times.

Other seemingly super-powered individuals won medals in both art and sport. Walter Winans, an American, was the first man to do so, winning gold for sculpture in 1912 (per Smithsonian Magazine). In the previous Olympics Games, Winans had been awarded a gold medal for shooting, per the The New York Times.

Nazi involvement in Olympics art competitions

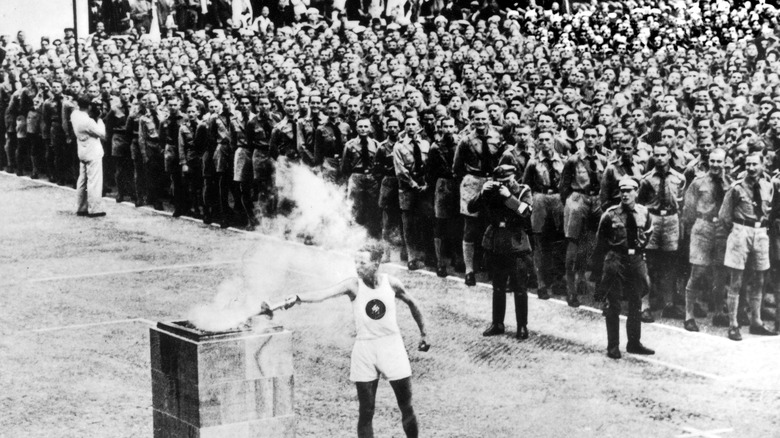

The 1936 Olympics in Berlin were perhaps the most controversial iteration of the Games in modern history, coming as they did in a militaristic nation that was amping up its aggression toward neighboring countries. In fact, many major nations — including the United States, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union — almost boycotted the event entirely, according to The Atlantic.

In the end, most countries ended up participating, including in the art competitions, which are "among the best-documented" in history, per The Atlantic. Joseph Goebbels, the Reich Minister of Propaganda, enforced a rule saying all submitted art should be made within the four years leading up the Games. As a result, many of the German submissions were direct reflections of Hitler's rise to power, The Atlantic reports. In the end, despite what at first seemed like a lack of enthusiasm from the German people, some 70,000 people came to see the displayed art.

The end of art in the Olympics

It was ongoing concerns about amateurism and professionalism in competition that ended art at the Olympics (via The Atlantic). For the most part, organizers of the Olympic Games were uninterested in having professionals compete, finding it fairer and more in the spirit of the games to restrict the art competitions to amateurs only, according to Smithsonian Magazine.

But ultimately, this adherence to amateurism would have created its own problems. The vast majority of artists who submitted their work to the Olympics were considered professionals (via the Olympics website). The few people who would have remained eligible were largely considered to be lacking in skill, meaning it was hard to get either judges or spectators excited about the winners, per The Atlantic.

Subsequently, when American Avery Brundage (pictured) became the head of the IOC in 1948, he decided to eliminate the art competitions, reports Smithsonian Magazine. Moving forward, the Olympics was marketed as a sports-only event.

New art competitions

Different forms of art competitions have been hosted alongside the Olympic Games since the official arts medal system was disbanded in 1948. One such competition is the Art and Sport Contest. This event gives out prizes as high as $30,000 for best sculpture and graphic art submissions from competing countries (via the Olympics website and the International Olympic Committee).

The IOC has also promoted art through non-competitive ventures, including through the Olympic Art Visions program, which commissions artists to create public artworks that are intended to "bring people together through the presentation of pioneering artworks in public spaces, and to encourage them to join in a fresh dialogue around the Olympic ideals and values," according to the Olympics website.

Another modern program, Olympism Made Visible, uses photography as a means to examine the societal effect of sports such as those featured in the Olympics. And Olympics Films is a program that hires directors to capture documentary films of the Games. But perhaps the best example of Pierre Coubertin's vision in practice is Olympian Artists, launched in PyeongChang, South Korea, in 2018. The program works with Olympians who are also artists to have them create art sharing their own vision of sport, according to the Olympics website. It might not quite be the same as winning a gold medal for sculpture, but it certainly spotlights multitalented individuals.

Where to find Olympic art now

Since the Olympics art medalling program was shut down in 1948, all 151 art medals have been removed from the official Olympic record, according to Smithsonian Magazine. That means winners — and the countries they represented — are no longer able to officially claim these past victories or add them to their total medal counts.

Unfortunately, the majority of winning pieces have mostly been lost or have fallen into obscurity, according to the Olympics website. One artwork you can still find: the Payne Whitney Gymnasium at Yale University, which was created by John Russell Pope (pictured), according to Mutual Art. Pope, who also designed the Jefferson Memorial in Washington, D.C., cinched an Olympic silver medal for his gymnasium design in 1932. Today, the gymnasium can still be found on Yale's campus. If you want to check it out yourself, simply take a trip over to New Haven, Connecticut, where you can enjoy some delicious pizza, a gorgeous view of the ocean, and the sight of an Olympic medal-winning piece of architecture.