Opera Nazionale Balilla: Fascist Italy's Version Of The Hitler Youth

Adolf Hitler. Nazis. Fascism. World War II. You'd be pretty hard-pressed to find someone who wasn't familiar with all of those terms. After all, it's tough to forget what was happening in Germany in the 1930s and '40s. However, when it comes to fascism in the early 20th century, Germany wasn't the only country embracing that ideology; for that matter, it wasn't even the first.

For that, you'd have to look to Italy and its fascist dictator, Benito Mussolini. Though Hitler might be more widely known and infamous in the modern day, Mussolini was the one who first founded a fascist party (and even coined the term) back in 1919, leading to his rise to power in 1922 (via the Constitutional Rights Foundation). Hitler took the idea and added his own spin on things, but this general political ideology wasn't the only similarity between the dictators.

If you know a thing or two about World War II, there's a decent chance you've heard of the Hitler Youth – the Nazi group created to indoctrinate young children with the principles of fascism. Well, as it turns out, fascist Italy had its very own version of a state-sponsored youth group, known as Opera Nazionale Balilla, more commonly referred to as just Balilla. And while the two groups are similar in some ways, Balilla has its own story.

Fascism focused on the youth

Looking at things generally, it's not a coincidence that both fascist Italy and Nazi Germany had prominent groups intended to indoctrinate young kids into wholly trusting their respective political parties. After all, fascism as a political ideology had a very vested interest in younger generations and the parts they could play in their nation's future.

According to Michael A. Ledeen's "Italian Fascism and Youth," fascism had a particular fascination with traits like vigor and creativity, linking them explicitly with this general idea of youthfulness. In turn, that youthfulness became connected to the idea of a revitalization – the restructuring and rebirth of Italy following World War I (via National Geographic), but also with a vision of Italy eventually leading the rest of Europe into a new future.

To make all of this work, though, Mussolini's government had to focus on the youth in a very literal sense, as well. He saw older generations as tainted with their experience of the Europe of the past, the Europe that didn't operate under fascism. In contrast, younger generations were pure, blank slates; they could grow up knowing nothing outside of fascism's influence, and that would make them, essentially, the perfect vehicles to spread fascism outside of Italy. And so Mussolini positioned himself as a champion of the youth, appealing to them, and creating groups like Balilla to teach them.

The name came from a historical figure

The logic behind the name "Opera Nazionale Balilla" might not be immediately obvious, and that's probably because there's a bit of historical context to go along with this particular aspect of the group. More specifically, as explained in an article published in the Journal of Modern Italian Studies, "Balilla" was chosen for a reason.

For that story, you have to go back a bit further in history, specifically to the War of Austrian Succession in the mid-1700s. While that war is a whole event on its own, the important part here is that December 5, 1746, was the date of a revolt in Genoa, per an article in Italian Studies. In short, locals weren't pleased with the occupation by the Habsburg army, and, as the story goes, the revolt was started off by a child who began throwing stones at the occupiers. While the true identity of that child is somewhat lost to time – although largely thought to be named Giovan Battista Perasso, historical sources never explicitly named any of the children involved in that skirmish – he became known in popular history as simply "Balilla."

And Balilla became something of a national hero. Sotheby's explains that Italians looked to him as a young revolutionary, someone who came to stand for independence and unity. Quite the fitting and effective namesake for a group of young people intended to bring Italy into its modern age, right?

The founding and growth of Opera Nazionale Balilla

Benito Mussolini's visions for his new Italy were ambitious, to say the least. So, fittingly, he couldn't just create the Balilla and call it a day. According to P. W. L. Cox's "Opera Nazionale Balilla: An Aspect of Italian Education," Mussolini appointed a new minister of education, Giovanni Gentile (via the Constitutional Rights Foundation), who began officially implementing fascist ideology into school curriculums. His program, called Reforma Gentile, meant to shift the goals of education from intellectual pursuits to decidedly more physical ones.

The real efficacy of this program can be debated, but it did form something of a basis for what the Balilla would become. According to an article from the Journal of Modern Italian Studies, the group was initially founded as the Avanguardie Giovanili Fasciste before being renamed the Opera Nazionale Balilla in 1926. A year later, in 1927, enrollment in Balilla numbered nearly half a million; seven years later, in 1934, and in part thanks to new subgroups of Balilla, enrollment had swelled to well over 4 million in total. By 1937, about half of Italians between the ages of 6 and 18 were reportedly a member of Balilla in one capacity or another.

That said, all of these numbers should be taken in context: 1937 also marked the year when enrollment became enforced by the state, and History Today adds even before that, enrollment was just a smart idea, being something of an unofficial prerequisite for things like jobs and scholarships.

They used propaganda to appeal to young people

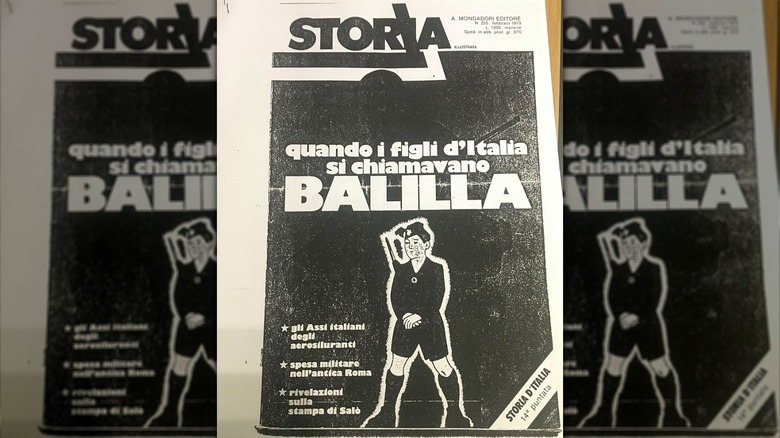

Propaganda from the early 20th century really isn't that surprising to see. So maybe it isn't too much of a shock to learn that it was quite the promotional tool for the Balilla, but they really did try very hard to sell this group to kids and teenagers (via the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum).

An exhibit of some of the advertisements displayed by the University of Wisconsin – Madison is extremely telling about what the fascist government was going for. Whether or not you can understand Italian, you understand the meaning of the art, depicting young men in stereotypically heroic poses, wielding their weapons with pride, and generally looking powerful. One photo even shows a young man vaulting himself over his colleagues, all of whom are carrying bayonets – quite an impressive show of athleticism. (Really, showing off physical prowess seems like something of a trend, with photos from All That's Interesting depicting a different fascist youth group putting on a large gymnastics show.) Or if feats of athletic ability weren't your thing, then there was the good old staple of appealing to kids by saying they can learn to fly planes. A cover of a propaganda magazine had a cartoon of two pilots flying over an Italian city, and the pages of that same magazine talked about how skilled Italian pilots were, hoping that young readers would take an interest.

Bright art, stories of heroism, feats of agility – none of those seem like bad ways to grab a child's attention.

Their outfits were a nod to the past

When you find photos of boys who were a part of Balilla, you get a good idea of what their uniforms included. Photos provided by All That's Interesting and WW2 Wings capture boys across a wide age range proudly wearing their sharp black shirts, matching boots, and caps, occasionally embellished with medals and draped cords. In a similar vein, older boys in the Avanguardisti had their own uniforms, with those choosing to join the military even getting specialized outfits for the type of unit they were planning to join. All in all, the clothing seems to closely resemble military dress uniforms, and with that in mind, History Today adds that those uniforms were actually a big part of the draw for these organizations. In short, the clothing was desirable; young boys responded well to that.

But it wasn't all about the aesthetic. In actuality, those black shirts had a much more symbolic meaning (via the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum). See, back in 1919, Benito Mussolini began his rise to power in earnest, using squads of fighters all dressed in black shirts to attack his political opponents (via the Constitutional Rights Foundation). Apparently, that image stuck, and Mussolini's allies in his revolution became known more colloquially as "Blackshirts." It followed that Balilla members would wear literal black shirts as their uniform, commemorating Mussolini's (and fascism's) rise to power.

Balilla was only one of multiple youth groups

If you were to look for photos of Balilla, it's pretty likely that you'd stumble upon images of young boys – probably between the ages of 6 and 18 – wearing their uniforms and taking part in group exercises. But really, Balilla actually had a more complicated structure than that; in fact, "Balilla" is something more of an umbrella term for a number of different fascist youth groups.

For one, the Balilla wasn't just a boys' club. An article from the Journal of Modern Italian Studies explains that the group expanded to include girls in 1929, dividing them into two different groups: the Piccole Italiane for girls between the ages of 8 and 14, and the Giovani Italiane for those between 14 and 18. Similarly, boys had different age groupings. The youngest – between 6 and 8 – joined the Figli Della Lupa, Italian for "sons of the she-wolf" (via History Today). From there, they could transfer to Balilla, and once they turned 15, they could join the Avanguardisti (via Oxford Reference).

It didn't end there, either. According to "Opera Nazionale Balilla: An Aspect of Italian Education," former Avanguardisti members could join the fascist militia and become part of the Young Fascists at age 18, eventually being allowed official entry to the fascist party when they turned 21. Or they could go the university route, joining the Centurie Universitarie to keep an eye and ear out for anti-fascist rhetoric on campus.

Balilla members learned military skills

In general, Italian fascism stressed vigor and physical fitness. It's what Giovanni Gentile prioritized in his new school curriculums, and considering many Balilla members joined the fascist militia, it only makes sense that they were trained to be soldiers from a young age (via "Opera Nazionale Balilla: An Aspect of Italian Education").

Young boys were taught general military tactics and techniques – how to fire guns and take part in drill exercises. When they got older, that training got more intense, including physical tasks like operating a machine gun as well as more mental tasks, such as leading drill exercises and learning the main statutes of fascist ideology. And, of course, underpinning this all was an emphasis on discipline and obedience, per All That's Interesting. Really, this is all rather well summarized by the oath taken by Balilla members: "In the name of God and of the Fatherland, I swear to follow the orders of the Duce and to serve with all my energy the cause of the Fascist revolution."

Oh, and if you were wondering about the young women who joined Balilla, well, perhaps unsurprisingly, they weren't taught things like military drills or marksmanship. Instead, they were taught housework and cooking, impressing upon them that fascist ideology required that they be submissive to their husbands and remain in domestic spaces.

Balilla toys promoted fascism

The way to any kid's heart: toys. Right? Well, that little bit of knowledge was apparently something that Italy's fascist government was also aware of, and it was something that they tried to exploit. Diana Garvin's article in the Journal of Modern Italian Studies explains that a couple of Italian toy makers began to achieve national fame around the rise of fascism, and so one of those companies began to make Balilla dolls. Oftentimes, these dolls were sold in pairs: the brother wore the dark, military-like uniform of Balilla (or Figlio di Lupa) members, and the sister's outfit (a black skirt, cap, and long-sleeved blouse) implied that she was a member of Piccola Italiana.

Much like Balilla itself, these toys were actually used as tools by the fascist government. Hailed by officials as the national toy, they modeled proper behavior and dress, normalizing fascist standards as the norm for any kid growing up at that time. Even playing with the dolls reinforced this idea; due to the construction of the dolls, the most natural position for their arms was the fascist salute. The Balilla dolls were essentially meant to help facilitate fascism's entrance into all parts of children's lives, narrowing their potential viewpoints. For that matter, the fascist government even prohibited that same company from selling dolls that broke with the gender norms they were pushing: A female doll wearing pants and smoking a cigarette was barred from being sold in Italy.

They had to contend with the Catholic church

Italy has a long history with Roman Catholicism, which is probably unsurprising, given, well, the location of Vatican City. Strangely enough, though, Vatican City was only created in 1929 (via Britannica) in a treaty that went into effect during Benito Mussolini's rule of Italy. While that treaty solved a longstanding problem between Italy and the Papal States, it ultimately caused more headaches for Mussolini when it came to fascist youth groups. After all, half of Italian youths joined fascist groups (via the Journal of Modern Italian Studies), but where was the other half?

According to an article published in The Catholic Historical Review, the Catholic church had long been sponsoring its own youth groups, and part of the aforementioned treaty allowed the church to continue recruiting children into its groups. Obviously, that created competition and that was a clear problem for Mussolini; kids in these Catholic youth groups would ultimately be more loyal to their faith, rather than to the state.

Mussolini tried to force these groups into irrelevant positions, and in the summer of 1931, he even moved to disband all Catholic youth groups. Pope Pius XI spoke out in protest, and tensions began to rise not only between church and state but also between members of these groups themselves as fights would break out on the streets. By September 1931, Mussolini was forced to reinstate his competition; ultimately, he was able to institute some restrictions, but Catholic groups still managed to affect enrollment in organizations like Balilla.

Mussolini actually wanted to target university students

Looking at the numbers alone, it's hard to say that Balilla wasn't successful in its aims. Half of all Italian youths were involved (via Journal of Modern Italian Studies) – that sure sounds like Balilla did its job. But funnily enough, that was never actually Benito Mussolini's aim.

While fascism got quite a bit of mileage out of targeting really young kids and raising them entirely in a fascist society, Mussolini really wanted to recruit university students quite a bit more, per "Italian Fascism and Youth." While kids could be indoctrinated, college students were much more effective messengers, able to actually perpetuate and spread fascist ideology. In fact, Mussolini actively put people on this project, monitoring the atmosphere on university campuses.

But that only ever informed him that his efforts were ultimately in vain. While some students seemed, at the very least, amenable to the ideas, many others had no interest in creating strong ties to his political party and were much more likely to scoff at the importance that fascism placed on discipline. What's more, many professors were staunch antifascists, and well-respected, at that. As such, it was difficult to convince college students to join up with Balilla when they more naturally agreed with their professors. Over the years, Mussolini and other members of his circle tried to appeal to older students, but always to no avail, and by 1935, the scattered nature of their attempts produced the opposite effect, pushing students away from the fascist party.