The Tragic Story Of The Reverse Underground Railroad

For several decades up until the start of the Civil War, a network known as the Underground Railroad operated in the U.S. to help slaves escape into the Northern States and sometimes to Canada. Despite the name, the network was not actually a railroad but a series of safe houses and special routes slaves could use during their escape toward freedom (via History). Abolitionist John Rankin best describes the Underground Railroad in his book, "The soldier, the battle, and the victory," when he explains that "it was so called because they who took passage on it disappeared from public view as really as if they had gone into the ground. After the fugitive slaves entered a depot on that road no trace of them could be found. They were secretly passed from one depot to another until they arrived in Canada."

Those who helped provide safe passage for those escaping were known as "operators" — farmers, ministers, newspaper editors, and even ship captains — who wanted to help. Harriet Tubman was one of the most accomplished operators of the Underground Railroad. Rankin, for his part, describes how he ended up involved in the Underground Railroad. His house sat within viewing distance of Kentucky, and as slaves discovered he was an abolitionist, they would run to his house. "I knew that there were anti-slavery men on Red Oak, at Decatur, and Sardinia, and hence I could send them to any one of those places." And so the escape routes were built.

The Reverse Underground Railroad was born in response to the original cause

While the Underground Railroad had many supporters in Northern states, not everybody was happy about the help escaped slaves were receiving. The Reverse Underground Railroad, which kidnapped Black people in northern states and forced them back into slavery in the South, was born out of this discontent and greed.

As part of an Osher Lifetime Learning Institute (OLLI) virtual lecture (via OLLI George Mason University, historian and author Dr. Richard Bell details that, as the name suggests, the Reverse Underground Railroad was the opposite of the Underground Railroad. In addition to capturing free Black people from the northern states, kidnappers and traffickers of the Reverse Underground Railroad also worked to recapture slaves that had managed to escape, as detailed by researcher Jon Musgrave (via The Chicago Tribune). And just as slaves escaped to the Underground Railroad using safe houses and special routes, historians have since discovered places that were once used by kidnappers from the Reverse Underground Railroad, such as an Old Slave House and two caves in Pennsylvania.

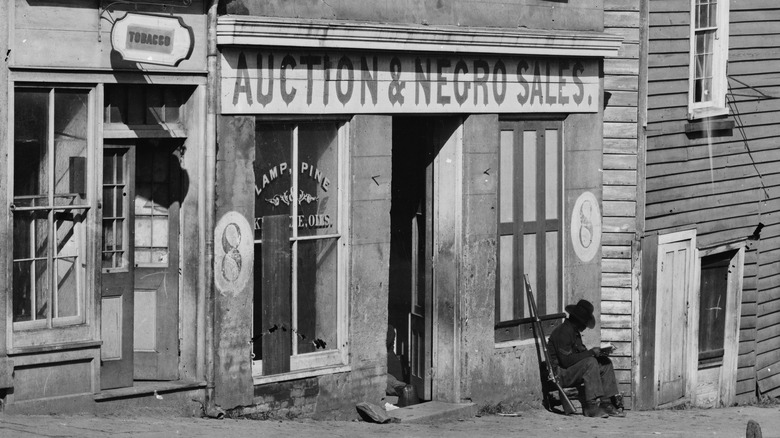

Money was the main reason behind the kidnapping of free Black people

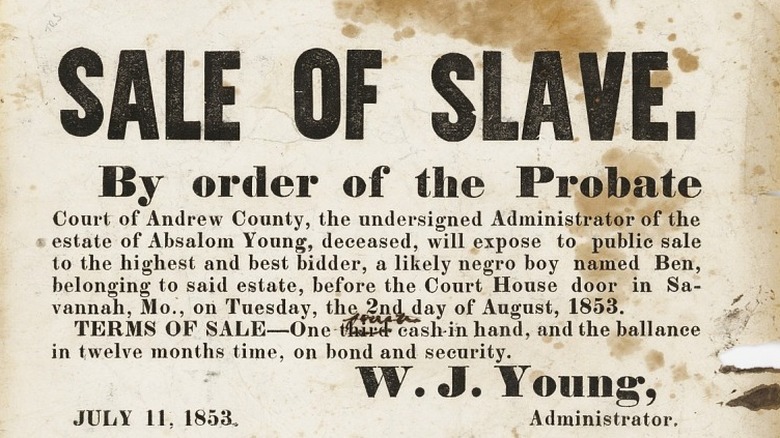

According to Richard Bell's "Stolen: Five Free Boys Kidnapped into Slavery and Their Astonishing Odyssey Home" (via American Heritage), there was one main catalyst behind the formation of the Reverse Underground Railroad: money. After legislation passed in 1808 to outlaw bringing slaves from Africa and the Caribbean, plantation owners in Southern states found themselves with a shrinking labor force — which actually increased the profits possible from the slave trade.

Enter the kidnappers of the Reverse Underground Railroad, who could sell a captured free Black person for as much as $700 ($15,000 in today's money). "The more settlers were willing to pay, the more tempting and profitable it became for unscrupulous entrepreneurs to kidnap free people," Bell says.

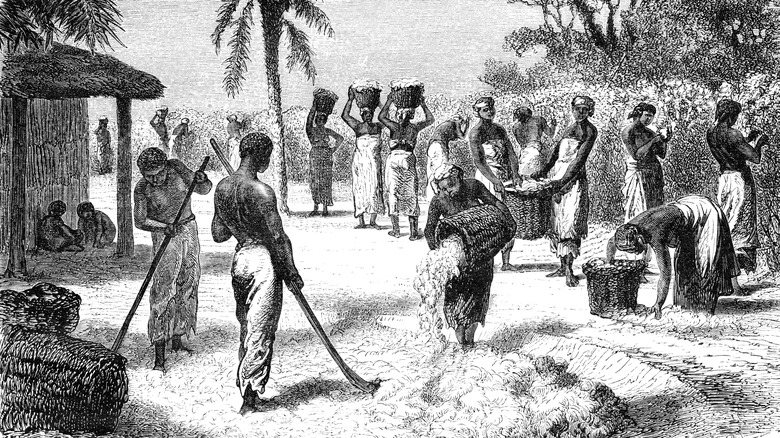

The slave market continued to grow in the country alongside the cotton market in the southwestern states. As noted by Carole Marks in her book, "Moses and the Monster and Miss Anne," farmers in the Southwest were willing to pay very high amounts for slaves: A slave that would sell for $300 in Virginia would get as much as $1,200 in states in the Southwest. As a result, a trade develop even among states in the South, where slaves born in a southern state would be sold to other states. It became such a profitable business, the price per slave continued to grow year after year, fueling the kidnapping surge.

For a long time, slave owners had a legal right to kidnap Black people

In 1793 and then in 1850, the federal government passed two Fugitive Slave Acts, which penalized people helping slaves to escape with up to six months in jail and permitted the kidnap and return of free Black people to their former owners. These acts were a direct response to the Northern States abolishing slavery (per History).

And while many Northern states simply ignored the law, the federal law remained in effect. In fact, the 1850 version not only allowed the government to capture runaway slaves but also told citizens it was their duty to help capture them. The new act also gave judges the right to decide if a captured person was in fact a fugitive slave without having to conduct a trial to confirm it (via Britannica).

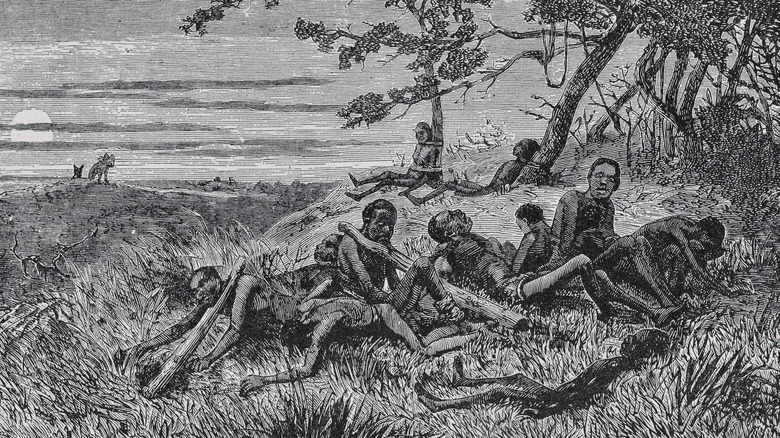

One important result of the passing of the act is that many runaway slaves in America made Canada (where runaway slaves were welcome) their new hopeful destination, according to a 1920 study published in The Journal of Negro History. For those who couldn't or wouldn't go to Canada right away, states like Ohio, Michigan, and Illinois became the first choice, as they were near the border with Canada and it would have been easy to run there for safety if needed.

Kidnappers used several tricks to trap free Black people

Many of the kidnappings that happened at the time of the Reverse Underground Railroad were violent. In his paper, "Black Kidnappings in the Wabash and Ohio Valleys of Illinois," researcher Jon Musgrave recounts the story of slave hunters breaking into homes as families were sleeping and kidnapping children, as well as landowners kidnapping their own freed slaves and then reselling them to other states.

Many kidnappers, however, used trickery to lure Black people into slavery. For example, in the book "A Portraiture of Domestic Slavery," author Jessie Torrey tells the story of a man from Philadelphia who forced mixed-race women into marrying him and then sold them as slaves. In the book, "Freedom at Risk: The Kidnapping of Free Blacks in America, 1780-1865" (via University Press of Kentucky), author Carol Wilson points out kidnappers sometimes approached a free Black person with a job offer or claimed a free Black person was actually a runaway slave — and with no proof to the contrary, the law often sided with them. In a paper published in "The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography," researcher Julie Winch gives another example of tricking parents with a promise that their child could learn a trade, only to then disappear with that child on the way to the South and never be seen again.

The kidnapping rings operated in several states

Although the Reverse Underground Railroad operated around the country, some states were more involved in kidnappings than others. According to Richard Bell in his Osher Lifetime Learning Institute (OLLI) virtual lecture, "early 19th-century Philadelphia was probably one of the most dangerous places to be free and Black anywhere in the United States, and this was a product of its location." At the time, Philadelphia sat very close to the border that separated the North from slave-owning states in the South, making it a very attractive place for people snatchers.

But Pennsylvania wasn't the only state where kidnappings were common. According to Carol Wilson in her book, "Freedom at Risk: The Kidnapping of Free Blacks in America, 1780-1865," this was true for all states bordering the Mason-Dixon line, including Delaware and Maryland, where a large number of free Black people could be found. That's not to say kidnappings didn't happen in other states. According to Wilson, people (and especially children) were kidnapped as far north as New Hampshire and as far south as Florida.

A gang in New York focused on kidnapping children

While kidnappers in the Reverse Underground Railroad took mostly men, this doesn't mean women and children were safe. In fact, a particular gang of kidnappers in New York focused on only taking and selling free Black children into slavery.

According to historian Jonathan Daniel Wells in his book, "The Kidnapping Club," the kidnapping of children in New York was unique because it involved a powerful network of bankers, judges, and lawyers who bent the law to make the kidnapping and selling of slaves a lot easier. The kidnappings included young girls walking to school, an adolescent boy who never returned from running to fetch something for his parents, and children simply being plucked from the streets. "It was almost too easy, especially when kidnapping rings knew that they had little to fear from white politicians, judges, and constables," Wells says. "The problem was not so much complacency as complicity: in fact some of the kidnappers were police officers themselves."

In a lecture via the Tewksbury Public Library, Wells explains that the so-called Kidnapping Club would also take anybody they could grab and claim they were runaway slaves — which was easy to get away with when judges and police officers were part of the "club."

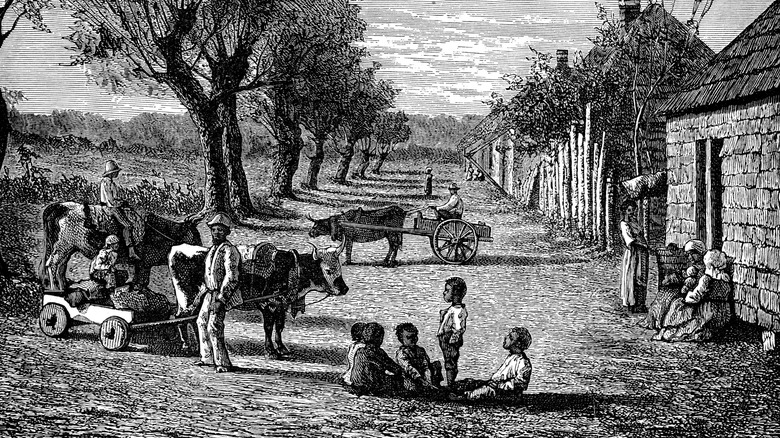

Kidnapped Black people were moved to the southern states through different routes

The Reverse Underground Railroad might not have been as organized in its route planning as the Underground Railroad, but kidnappers had plans and hiding spaces in place to help them move captured people to the southern states. Even if stopped or discovered along the way, many had false "bills of sale" to explain the Black men or children traveling with them, according to a paper published in The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography.

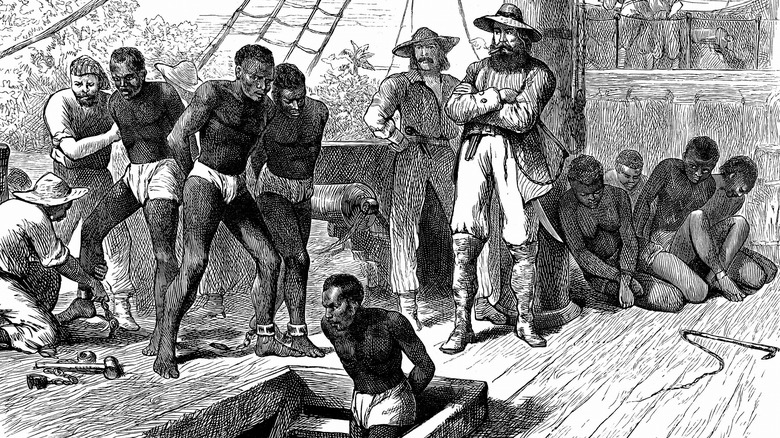

Once captured, the kidnapping routes often included a brief stop in a basement or out-of-the-way property before they could be ushered into boats heading to the south via the "waters of Maryland and Delaware." These water routes could take a week or longer, and once captors and captured would arrive in the South, they would be taken to houses of slave owners or other kidnappers before they would move on to their next stop deeper south. Routes usually included a mix of water and road transportation, as well as a long trek to their final destination (and often through the state of Alabama), which made it easier to conceal the kidnappers' tracks.

The travel conditions of the kidnapped were deadly

While being kidnapped was in itself a traumatic experience, for most captured free Black people, this was just the beginning of the nightmare. After the capture, their grueling route toward southern states would start. In his book "Stolen" (via Progressive Magazine), Richard Bell describes an example of how five kidnapped children between ages 8 and 15 were taken from a Philadelphia neighborhood all the way to Alabama.

Their journey there included a trip in a vessel resembling a "dungeon," being shackled in a windowless room, and a "1,000-mile-long trek" to the south that was accomplished mostly by walking. This was the standard, Bell explains in the book (via American Heritage), adding that "Very few of their captives traveled by ship to New Orleans. Instead, kidnappers forced most boys and girls to trek southward on foot in small, specialized overland convoys."

One of the children managed to escape along the way, but was promptly recaptured and whipped for his "offense." Another died a few months later shortly after a brutal beating. Captured free Black people marching to their final destination were often whipped along the way for things like complaining and walking too slowly. Other reports detail instances of frostbite along the route, and many died along the way, unable to complete the trek (via The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography).

Little was done to deal with the kidnappings

Kidnappers were rarely caught and even more rarely punished. Victim testimony wasn't available; it was easy for kidnappers to change their names or move somewhere else to continue with their "business"; and information circulated quite slowly among the population, so many weren't aware of the risks around them, according to a paper published in The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography.

Well-organized kidnapping rings were particularly tricky to identify and penalize, as captured free Black people could be moved toward southern states quickly before anybody could catch the kidnappers. Paper author Julie Winch points out that it also didn't help that the white population of Philadelphia (where many of the kidnappings took place) wasn't exactly happy about Black people living in the city and that "many whites watched the rapid growth of the black population with alarm and dismay." The result is that many ended up turning a blind eye to the kidnappings and violence.

Well-known slave trader kidnappers

Although the network of kidnappers in the Reverse Underground Railroad was extensive, some kidnappers became infamous for their tactics, brutality, or simply the number of people they kidnapped.

Patty Cannon and the Cannon-Johnson Gang are good examples. Led by a woman and operating in the Delaware and Maryland area, the gang was responsible for kidnapping and selling hundreds of free Black people into slavery, according to a historical marker located near the border of Delaware and Maryland. When Cannon's former slave, Cyrus James, was caught, he told the court he had seen Cannon murder several people, including a Black woman's child. While most of the gang managed to escape, Cannon was arrested but died in her cell while awaiting trial (per the Maryland State Archives).

Salt miner and businessman John Hart Crenshaw was also notorious for building much of his fortune on the trade of slaves he would capture and then sell for profit (per Illinois State Historic Preservation Office). He would eventually be arrested for kidnapping a Black woman and her children and holding them on his property but was released on a technicality.

Solomon Northup's experience

Perhaps the most famous victim of the Reverse Underground Railroad is Solomon Northup, whose story was popularized in the Oscar-winning movie, "12 Years a Slave." Northup was born a free man in New York in 1807 and throughout his younger life worked as a farmer and laborer on his family farm (His father was a freed slave who owned his own land.) and played the violin in his free time, according to Britannica. By 1841, Northup, his wife, and his children were living in another city, where he was earning a living through odd jobs. It was there that he was approached by two men and offered a job as a violin player in the circus.

Needless to say, there was no circus and no job, and when Northup arrived in Washington, D.C., he was drugged and kidnapped. He was eventually sold at a slave market in Louisiana and spent the following 12 years as a slave. A New York Times article from 1853 (via Documenting the American South) recounts the condition in which Northup lived for over a decade, including being lashed by his master, sleeping on a wooden board with no mattress, and living in a poorly constructed space that offered little protection from the elements. It wasn't until 1852 that Northup managed to send a letter to friends in New York City, who put things in motion and eventually helped release him.