Tragic Details About The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

Among all of the atrocities and tragedies of World War II, the Holocaust stands out as particularly heinous and horrifying. According to History, Adolf Hitler and the Nazis murdered approximately 11 million people during the Holocaust, roughly 6 million of them Jews. Many of them were killed in extermination camps located in occupied-Poland, including the infamous death factories of Auschwitz-Birkenau, Treblinka, and Sobibor.

Prisoners were gassed in these camps from 1942-1945, and millions more went to other concentration camps where they often perished performing hard labor. Jewish residents from throughout Nazi-occupied Europe were sent to the concentration camps, including many from the Warsaw Ghetto in Poland. In the Spring of 1943, the remaining residents of the Warsaw Ghetto rose up against the Nazis and staged a rebellion known as the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.

Though it ultimately failed, it was an incredible show of resilience and courage on the part of the Jewish resistance fighters. Thousands ended up dying in the end, and those who survived were dealt with harshly by the Nazis. Its been several decades since the insurrection took place, but it is no less important in the eyes of history. These are tragic details about the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.

Conditions in the ghetto were already atrocious

World War II began in late 1939, and the city of Warsaw, Poland, was one of the first to feel the Nazi's terrifying wrath, according to the National WWII Museum. There were just shy of 400,000 Jewish residents in the city, and they were immediately singled out by the occupying Germans for harsh treatment. Soon, the Nazis made Jewish residents wear identifying armbands, and after months of greater and greater repression, in October of 1940 they ordered the formation of the Warsaw Ghetto.

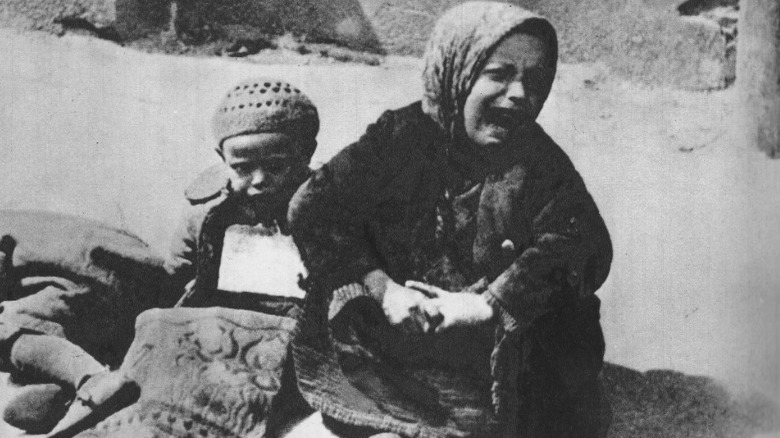

All Jewish residents were forced to live inside, trapped behind a massive 10-foot-tall wall with barbed wire on top of it. Roughly 450,000 Jews were forced to live in an area of barely 1.3 miles, and conditions quickly deteriorated. According to the Holocaust Encyclopedia, there was a severe lack of food, and diseases spread rampantly. Roughly 83,000 people, including many children, died due to a lack of food and medicine.

Typhus was responsible for a great many of the deaths, and thousands each month were dying by the summer of 1941. The ghetto was partly administered by a Jewish Council and Jewish police force, who had to carry out the bidding of the Nazis, which largely alienated them from their non-collaborator neighbors.

The deportations under the SS

After the Warsaw Ghetto had been in existence for just under two years, the Nazis began to exterminate the population in July 1942. According to Abraham Lewin in "A Cup of Tears: A Diary of the Warsaw Ghetto," at first, when rumors reached the Jewish population the Germans tried to deny that anything was happening. They told Adam Czerniakow, the head of the Jewish Council that partly administered the ghetto, that nothing was going to happen. However, starting on July 22, the Nazis began deporting between 2,000-10,000 residents a day to the Treblinka death camp.

The Nazis ended up deporting just over 235,000 Jews from Warsaw to Treblinka between July and early September, intending for the remaining residents to be used as slave laborers. As Warsaw Ghetto survivor Vladka Meed recalled in her autobiography, "On Both Sides of the Wall: Memoirs From the Warsaw Ghetto," residents were shocked when the deportations started happening. People were in a panic to obtain employment cards, which the Germans told them would allow them to escape deportation.

According to History, of the nearly 400,000 Jews in the ghetto, barely 55,000-60,000 were left following the deportations. Those who were left began to form militant self-defense groups, including the famous Jewish Combat Organization (ZOB), and prepared to fight back against the Nazis.

The failed January uprising

While still under the Nazi-German occupation, Jewish residents and the Jewish Combat Organization (ZOB) began to engage in acts of sabotage against the Nazis. This included various assassinations of Jewish collaborators, many of whom worked for the very hated Jewish police (via Abraham Lewin in "A Cup of Tears: A Diary of the Warsaw Ghetto"). In November 1942, rumors began to circulate about another deportation of Jewish residents, this one likely to include everyone who remained.

However, in the months prior, the militant Jewish groups began to plan for an uprising against the Nazis (per Warsaw Ghetto Uprising participant Yitzhak Zuckerman in "Warsaw Ghetto Uprising"). Fighting broke out on January 18, 1943, when the Germans tried to deport more Jews, writes Simhah Rotem in "Memoirs of a Warsaw Ghetto Fighters: The Past Within Me." Though the ZOB only had limited weapons, including just a few pistols, sticks, and knives, they managed to surprise the Germans and actually push them back, stealing German weapons in the process.

According to Marek Edelman in "The Ghetto Fights," the ZOB had only 10 pistols, which they had gotten just in time in late December, and the group was very disorganized. Many ZOB members were killed and several taken prisoner. In addition, it only brought them a brief respite, as within three months the Nazis had decided to eliminate the rest of the ghetto, resistance or not.

The Jewish collaborators with the Germans

In order to carry out many of their plans, the Nazis created a police force of Jewish residents who were forced to implement their orders. According to Vladka Meed in "On Both Sides of the Wall," the Jewish police were widely reviled among the residents for many reasons. Not only did they help the Germans carry out their dastardly orders, but they and their families seemed to be exempt from deportation.

The Nazis used the Jewish collaborators to help them round up and send Jewish residents to the railway station, which would ultimately take them to Treblinka and their deaths. Many of them were bitter and acted belligerently towards their fellow Jewish neighbors, which only increased the distaste for them.

As Marek Edelman explains in "The Ghetto Fights," some of the Jewish collaborators even worked with the Gestapo, who were the Nazi secret police. One of them may have even been working with them as far back as 1933, which would have far predated the war by over half a decade. In retaliation, the ZOB began to execute suspected Jewish Gestapo agents, including Alfred Nossig, one of the most infamous Jewish collaborators in history.

Image by Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-270-0298-11/Amthor via Wikimedia Commons|cropped and scaled | CC-BY-SA 3.0

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising began on Passover eve

Following the failed January uprising and numerous assassinations by the Jewish Combat Organization (ZOB), the Nazis entered the Warsaw Ghetto on April 19, 1943, to begin their final deportation and extermination of the Jewish population. As the Holocaust Encyclopedia points out, April 19 was the day before the Jewish holiday of Passover, which celebrates the Ancient Israelites' escape from bondage.

According to Jewish ZOB fighter Marek Edelman in "The Ghetto Fights," though they knew they were heavily outnumbered, the Jewish resistance fighters prepared to fight the Nazis in a last ditch attempt to stop the deportations from occurring. As soon as the Germans entered the intersection at Mila Street and Zamenhofa Street, members of the ZOB started to open fire. The first battle raged for just over seven hours, and in the end there were casualties on both sides.

Several Germans who were killed in the fighting had their weapons taken by Jewish partisans for use against their fellow soldiers, and the ZOB managed to destroy two tanks. Unfortunately, the Germans were soon able to reverse their defeats, and by May 8, an estimated 80% of the Jewish resistance had died.

The ghetto became engulfed in an inferno

Through the first few days of the fighting, the Jewish resistance fighters held their own against the Nazi invaders. However, as R. Conrad Stein explains in "World at War: Warsaw Ghetto," the partisans were in an obviously losing situation. Limited by a lack of arms, ammunition, and personnel, there was only so long they could reasonably expect to hold out. Still, their initial resilience surprised and angered the Nazis.

Unable to dislodge the most vigorous of fighters, the Nazis decided to burn the ghetto to the ground. Many of the fighters preferred to burn to death instead of surrender to the Nazis, and countless resistance members perished in burning buildings set alight by flamethrowers. According to Marek Edelman in "The Ghetto Fights," the raging inferno killed thousands of residents and forced many to flee their safehouses and shelters. With nowhere to turn, many were either shot or rounded up by the occupying Germans.

Soon, bodies littered the streets of the ghetto, some of them half burned. Chillingly, as the Warsaw ghetto burned, the non-Jewish residents of Warsaw were able to party and celebrate the Easter holiday (per Elaine Landau in "The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.")

The Jewish resistance was forced to hide in the sewers

As the fighting intensified over the weeks of April and May, the situation became more and more desperate for the Jewish resistance fighters. Cut off from outside support and slowly being engulfed by flames and invading Nazis, the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising was quickly enveloped in chaos and confusion. Soon, it became clear that the only way to get out of the ghetto was through the underground sewer system (via Elaine Landau in "The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising").

If Jews could escape through the sewers they could reach the "Aryan" side of Warsaw, which was not under attack. Though it was a harrowing prospect that would yield uncertain results, Jewish residents were so demoralized and scared that they had little choice but to consider it. According to Simhah Rotem in "Memoirs of a Warsaw Ghetto Fighter," the initial plan to breakout of the sewers was slated for May 7, 1943, but was abandoned when the Nazis had stationed troops at the sewers to be on guard for any Jewish resistors.

Another breakout was planned for the following night, but by then many residents were too weak to make it to the sewers. Countless others lay dead or wounded in the streets, with the Warsaw Ghetto becoming their grave. Luckily, partisans were able to save many from the sewer system, though it was nothing in comparison with those they lost.

Many Warsaw residents took their own lives

As tragic as it sounds, many Jewish residents and fighters opted to take their own lives rather than face the Nazi invaders and almost surefire execution or deportation to an extermination camp. As Marek Edelman wrote in "The Ghetto Fights," many residents found themselves in burning buildings or shelters once the Nazis decided to set fire to the ghetto, and countless of them ended up jumping from the buildings to their deaths. In extraordinarily harrowing acts, some parents made the decision to die by suicide with their kids via jumping to avoid the agonizing pain of their children burning to death.

In another morbidly depressing story, Elaine Landau relates in "The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising" how a Polish firefighter callously refused to extinguish the fire engulfing a Jewish man and his baby, instead asking them to give him their valuables before they decided to jump. One of the leaders of the resistance, Mordecai Anielewicz, found himself trapped in the sewers and opted to end his own life instead of facing death at the hands of the Germans (via R. Conrad Stein in "Warsaw Ghetto").

The destruction of the Tłomacki Synagogue

Even though the Jewish resistance fighters fought courageously and valiantly, there was never any realistic chance they would have been able to overcome the odds. As the Holocaust Encyclopedia notes, there were roughly 700 Jewish fighters taking on approximately 2,000 German fighters, and the German fighters were trained whereas the Jewish resistance were guerillas.

Not only that, but armament wise there was nothing even close to parity. While the Jews had limited firearms and ammunition, the Nazis had heavy weapons, artillery, and even tanks at their disposal. The Jewish fighters relied on guerilla warfare tactics, but in less than a month the last of the resistance had been quieted.

On May 16, 1943, the Nazis declared victory, after having completely burned and destroyed the ghetto. By then, thousands of Jews had been killed either in the fighting or in the flames, and resistance was only sporadic. After the final operations, the German commander Jurgen Stroop had the Great Tłomacki Synagogue blown up (via PBS). Such a callous and unsympathetic measure put a horrifying exclamation mark on an already dastardly affair.

The survivors struggled to find shelter

Following the Nazi onslaught in the ghetto, the survivors from Warsaw struggled to find shelter. Some of them were able to escape and survive on the "Aryan" side of the town, but that did not mean that they had it easy (per Vladka Meed in "On Both Sides of the Wall"). Not only were they hopelessly demoralized after seeing so many friends and family members killed and their entire home burned to the ground, but they still had to evade the Nazis and unsympathetic Poles.

There were constant patrols being conducted by the S.S. and Gestapo agents, and posters were put up that warned about potential Jews in the area. The Nazis burst into Polish homes in search of suspected hidden Jews, and upon finding some in one house they murdered the family and burned down the home.

Residents were afraid to offer their homes to fleeing Jews, and only some were willing to take on the risks of housing them. Those who had more discernible Jewish features were in even greater peril, as just walking around could get them arrested and deported. They were forced to stay inside the same room for days on end at times and only learned about the outside world through their few friendly contacts.

The horrific death toll

The entirety of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising lasted just short of a month, and the death toll was devastating. According to the Holocaust Encyclopedia, roughly 7,000 Jewish residents died defending the ghetto against the Nazis. Another 7,000 were captured and sent immediately to Treblinka to be killed. On top of this, another 42,000 were captured and sent to concentration camps to do hard labor. A few months later, in November, many of them would perish during Operation Harvest Festival, a Nazi killing frenzy that resulted in another 42,000 murders in Lublin, Poland.

Many of the 7,000 killed were not fighters and were just civilians caught up in the ordeal. According to Elaine Landau in "The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising," the S.S. guards in Warsaw would round up huge scores of Jewish residents and execute them by firing squad in the courtyard of the nearby prison. They did so because there were already so many Jews in line at the railway stations to be deported to death camps and labor camps, and they carried out much of the killing on Easter Sunday.

Even the Jewish collaborators with the Nazis were summarily murdered and their bodies burned. In one tragic instance, a family, desperately hiding in a bunker from the Nazis, accidently killed their child in a misguided effort to stop him from making too much noise.

The Warsaw prison camp

In November 1940, shortly after the formation of the Warsaw ghetto, the Nazis also created the Warsaw prison camp. Known as Gęsiówka, the camp was located on Gęsia Street and could hold between 300 to 1,300 prisoners (via the POLIN Museum of History of Polish Jews). The conditions were abhorrent, the space was incredibly cramped, and many were murdered in the courtyard.

Following the failed uprising, the Nazis closed Gęsiówka, but only briefly. It became part of the wider Majdanek concentration camp, and many Jews were sent there from far away countries to provide free labor. They had to dig through the completely destroyed ghetto to find valuables from murdered Jews that they could turn into the Nazis. By August 1944, there were barely 350 Jews left when the second Warsaw Uprising occurred. Those who still remained were liberated, and some ended up fighting against the Nazis in the failed uprising.

There is a plaque at the spot of the former Gęsiówka prison camp, which memorializes those who were liberated in 1944 and participated in the second uprising.

The failed second uprising

After the ghetto was demolished during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, there were barely 20,000 Jews remaining out of an original population of more than 400,000 (per the Holocaust Encyclopedia). Many of them were still in the city a year and a half later when the Warsaw Uprising of 1944 began. They had been forced to live on the "Aryan" side of the city, which had escaped the destruction of the ghetto.

Beginning in August 1944, the remaining residents of Warsaw, who had also been living under less brutal Nazi occupation, staged their own revolt known as the Warsaw Uprising. Incredibly, some of the Jewish fighters who had participated in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of 1943 found themselves fighting during the uprising of 1944 (via the National WWII Museum).

They were discriminated against by the non-Jewish Poles and restricted from joining some of the battalions, but others accepted them and allowed them to fight the Nazis once again. Ultimately, the 1944 uprising failed too, and many Jews who had survived the 1943 uprising perished in 1944.