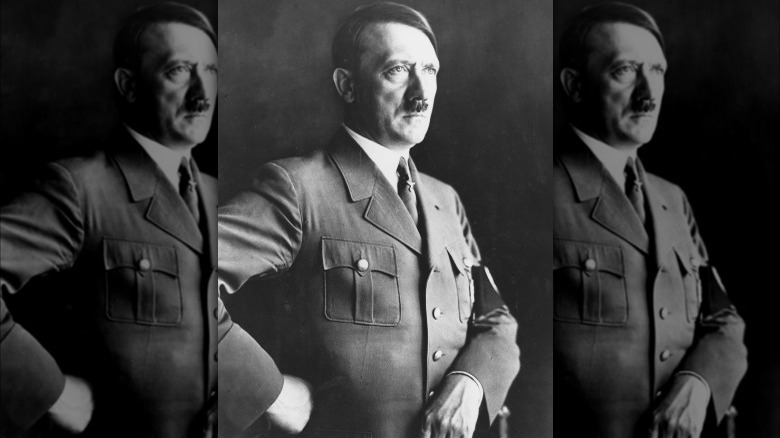

Why Adolf Hitler's Mentor Eventually Broke Away From Him

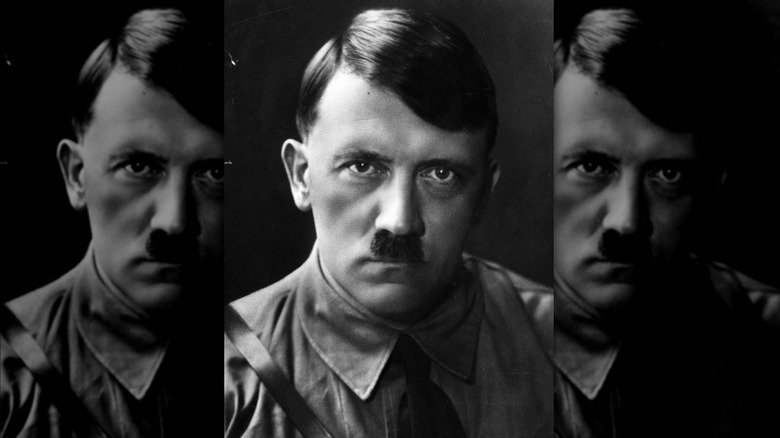

Adolf Hitler's reign of terror came to an end upon his death by suicide in 1945 (per History). In its wake, between 70 and 85 million people had perished in World War II, sparked by Hitler's invasion of Poland amid years of rising tensions that came to a head (per the Council on Foreign Relations).

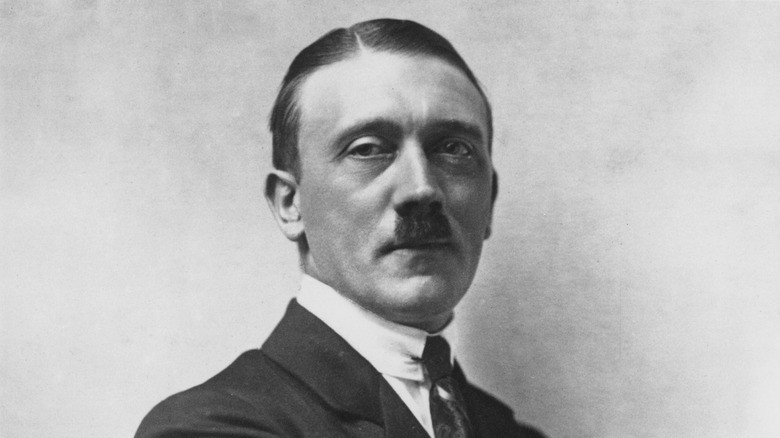

The violence of Hitler's reign was vast. From the systematic execution of millions of Jewish people to horrific medical experiments that put prisoners through excruciating torture, his legacy of atrocities has not waned throughout the years. But Hitler did not grow into the person he was on his own — like many others, he was influenced by the people around him. One such influence was Dietrich Eckart, a poet who guided many of the future dictator's beliefs and actions and helped mold the Hitler that would eventually lead the Nazi Party. Yet as the years passed, the former playwright grew to disagree with the Nazi leader's methods.

Eckart's turn to fascism

Dietrich Eckart was born in Neumarkt, Germany in 1868 (via Jewish Virtual Library). He went on to study medicine in Munich but turned to the world of art in 1891. He set his sights on poetry, playwriting, and journalism, though he had varying degrees of success. His father died in 1895, leaving him parentless following the early death of his mother.

Eckart blamed society for his failures as a playwright. Eventually, he landed at the anti-semitic periodical Auf gut Deutsch, where he worked between 1918 and 1920. Here, he was able to express his beliefs that Jewish people and social democrats were the reason for Germany's failure in World War I. He also wrote "Deutschland erwache" ("Germany awake"), which the Nazi Party eventually adopted as its anthem.

The song was adopted, of course, under the leadership of Adolf Hitler, who Eckart met in 1919 while working at Auf gut Deutsch.

A meeting of hate

On May 30, 1919, Hitler attended a German Workers Party (GWP) meeting at the behest of Captain Karl Mayr (via Spartacus Educational). Dietrich Eckart had joined the party just months earlier in January 1919, and it was at this event that he and Hitler first met. Interestingly, Hitler was not impressed with this meeting — despite agreeing with the antisemitism and German nationalism espoused by founder Anton Drexler and others.

Hitler expressed his discontent, and his passion impressed Drexler, who attempted to recruit the future dictator. "I didn't know whether to be angry or to laugh," Hitler wrote in "Mein Kampf." "I had no intention of joining a ready-made party, but wanted to found one of my own. What they asked of me was presumptuous and out of the question."

Hitler eventually joined the party and — along with Eckart, Drexler, and Gottfried Feder — went on to pen "Twenty-Five Points" in February 1920. According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the programme of the party was a mix of antisemitism, nationalism, and socialist proposals, the latter "greatly influenced" by Feder (per Spartacus Educational). Such concepts were driven by anger at the German loss in World War I and the subsequent Versailles peace settlement, which required the country to give up its overseas possessions and forfeit 10% of its prewar territory in Europe.

Eckart coached Hitler

The charisma of Adolf Hitler has long been discussed as a facet of his rise to power. BBC News defined it as "dark charisma" and called him the "archetypal charismatic leader." His aide, Fritz Wiedemann, said that he was fixated on the idea of celebrity (via Newsweek). (As far as his work ethic, The Hollywood Reporter says he reportedly slept until at least 11 a.m. — even in Berlin — and watched a movie every night.)

It appears that Dietrich Eckart helped him develop his "dark charisma." According to Biographics, Eckart coached Hitler to help him develop his ability to appeal to the masses by honing the way he dressed, acted, and spoke. Using these skills, Hitler was able to passionately connect his hateful ideology with the crowds he rallied. Of course, he was also trained on how to mask the angrier, more spiteful aspects of his persona when he needed to appeal to the upper echelons of society — something Eckart realized was necessary for the Nazy Party's success.

The strategy worked — Hitler was able to recruit aristocrats and industrialists to support or finance the GWP.

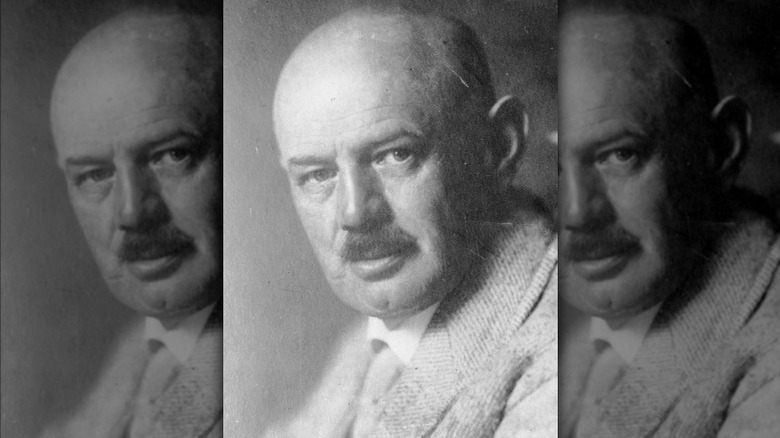

Eckart eventually broke away from Hitler

The cracks in Dietrich Eckart and Adolf Hitler's relationship began to show when Hitler quit the GWP on July 11, 1921, following a clash Drexler, who pushed for the party to align itself more closely with socialists (via Biographics). Eckart intervened and convinced Hitler to return — and become the leader of the Nazi Party. Though Eckart supported Hitler in recruiting the paramilitary Brownshirts, the leader began to carve his own course as the former playwright started to experience health issues.

In August, Eckart moved to the Bavarian Alps, and it was here that he began to see things differently than his former protege and almost completely withdrew from his former activism. Per Biographics, amid Hitler's four-day rally in Munich in January 1923, Eckart "lamented that his mentee relied too much on violence" and suggested that he was developing a "messiah complex." Despite this, Hitler defended Eckart and helped him escape Munich in disguise after the magistrate issued an arrest warrant against him.

Final days

Though Dietrich Eckart participated in Hitler's failed Beer Hall Putsch, he ultimately spent his final days in poor health and financial straits (via Biographics). He died in Berchtesgaden on December 26, 1923, from a heart attack brought on by morphine addiction. Hitler, of course, would go on to plunge the world into the Second World War and die by suicide on April 30, 1945 (per History).

Despite the fact that the pair drifted apart, Hitler still had affection for his mentor and even dedicated the first volume of "Mein Kampf" to his friend (per Jewish Virtual Library). Eckart's biographer, Louis L. Snyder, said of their relationship (per Spartacus Educational): "The two were inseparable. Hitler never forgot his early sponsor ... Hitler, he said, was his North Star ... He spoke emotionally of his fatherly friend, and there were often tears in his eyes when he mentioned Eckart's name."

In the end, it seems that Hitler would not have been the same person without the influence of Eckart — two men who related in their failures and a hatred for what they perceived to be the cause of their despair. As journalist Konrad Heiden said: "Eckart was the same sort of uprooted, agitated, and far from immaculate soul ... He could tell Hitler that he (like Hitler himself) had lodged in flop-houses and slept on park benches because of Jewish machinations which (in his case) had prevented him from becoming a successful playwright."