The Side Effects Of Cannibalism

Cannibalism isn't a rare form of sustenance in the animal kingdom. Various species of spiders are known to routinely practice it, as well as several members of the insect kingdom, including the praying mantis and some ladybugs (via Wildlife Informer). Incidents of cannibalism are also recurring among some mammals, though the practice of one mammal dining on another of its kind is usually the result of food scarcity or environmental stress.

You wouldn't have to do much research to discover incidents of cannibalism among fellow human beings, either, though it has long been taboo in almost all parts of the globe, with most documented cases centering around desperately staving off starvation. In fact, history has many grim examples of people eating the flesh of other people to survive. The ill-fated Donner Party, the famines in China following Mao's Great Leap Forward (via Canada Free Press), and the survivors of a plane crash in the Andes mountains in 1972 (inspiring the movie "Alive)" are all tragic examples of how people were put into a position where their choices were to eat the remains of loved ones or starve (per History). Sprinkle a serial killer like Jeffrey Dahmer into the mix, and you almost get a full picture of why cannibalism has been committed.

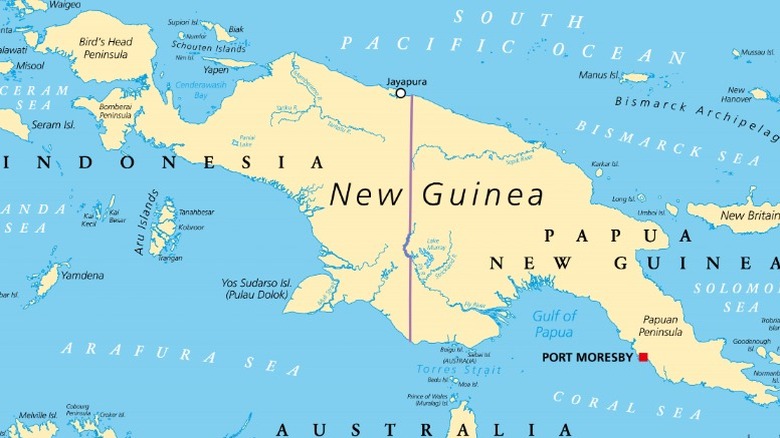

But some cultures, even ones in recent times, have eaten human remains for a different reason. The ritual of eating the dead had long been a custom of the Fore people of Papua New Guinea, but as time went on, eating human flesh was shown to be a deadly choice of cuisine (per NPR).

The Fore people in New Guinea believed that they were under a spell

NPR reports of the remote area of Papua New Guinea that the rest of the world believed to be uninhabited until about a century ago when gold prospectors from Australia explored the highlands. They estimated that there were around a million people who called the highlands home, living in small villages. Two decades later, researchers began to arrive in this remote region and logged terrifying findings.

The tribe they were gathering information on was called Fore. There were about 11,000 members, making up a tiny percentage of the highland population. Locals believed that this tribe was the target of some sort of spell or curse, as more than 200 of them died every year from what the Fore called "kuru." Kuru is a Fore word that means "shaking" or "trembling," some of the first signs that the disease has infested one of their members. The infected person would begin to slowly lose control of their muscles and eventually would become immobile. They would be in such dire straights that they would be unable to walk or even feed themselves. As the condition worsened, they would lose control of bodily functions, becoming almost infantile.

Perhaps the eeriest part of what the researchers observed was the loss of emotional control these poor souls fell subject to. The Fore would refer to it as "laughing death," with the infected sometimes laughing maniacally as they slowly withered away.

It was discovered that the Fore tribe had an unusual ritual

With an estimated 200 members of the Fore tribe dying from this condition each year, it was feared that they were heading down the road of extinction (per NPR). Researchers noticed that whatever the ailment was, it had taken a toll on the female population in particular. Several villages seemed to have no women left at all. Young children were also suspiciously targeted by whatever it was that was causing kuru.

For years, kuru was studied as researchers tried to isolate a cause, and for a time it was believed to be a rare genetic condition. This prompted medical anthropologist Dr. Shirley Lindenbaum to visit the Fore villages and put together family trees in hopes of settling whether kuru was an inherited disease or not. What she discovered was something that might shock people in the Western world.

The Fore practiced a custom known as funerary cannibalism. They held the belief that the bodies were sacred and better to be consumed by the people who loved them than by scavengers, bugs, or larvae. The women were believed to be the ones who could take the body into their own and keep it safe from any evil spirits that might have contaminated it. They would cook the brain and the flesh and dine on them as a religious rite. Their young children would often tend to these ceremonies with them and were given the cooked remains to consume with their mothers.

Kuru is a neurodegenerative disorder that is passed on through cannibalism

Dr. Lindenbaum was able to persuade other researchers that kuru was rooted in the Fore practice of funerary cannibalism. Several years later, NPR reports that the National Institutes of Health injected chimpanzees with matter from an infected human brain. It worked its way slowly through the apes, but the ones injected with it developed kuru. The experiments and research were conducted by a team that was headed by Dr. D. Carleton Gajdusek, who won a Nobel Prize in the 1970s for his work with kuru (per Nobel Prize).

Scientists knew the cause of kuru, but they still weren't sure of what it was. A disease? A virus? The jury was still out on that until two decades later when Stanley B. Prusiner made a groundbreaking discovery (per Nobel Prize). A biologist, Prusiner had discovered proteins that had unusual characteristics — the protein strands he observed were folded over and performed both normal and disease-carrying functions. Prusiner named these proteins prions. They would transmit the disease-carrying function to nearby proteins in the brain, generating an infectious chain reaction that led to brain damage over time (per The American Association of Immunologists).

His discovery of prions and the subsequent work he performed earned him the 1997 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (via Nobel Prize). Prions have been identified as the culprit for the rare Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and fatal insomnia (via Johns Hopkins). Prions may also be a cause of Alzheimer's disease.

The Fore people's women and children were the most affected by Kuru

It's not possible to say exactly how kuru began infecting the Fore people of New Guinea, but researchers do have one pretty solid theory. They noted the spread of kuru cases from one part of the highlands to another to another, showing a slow chain reaction of the fatal disease traveling from Fore village to Fore village. They surmise that at one point, a member of the Fore tribe contracted Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Loved ones ate the body of the stricken person after they died and became infected with kuru (per NPR). Kuru symptoms do not occur overnight — the condition is very slow-moving, sometimes taking more than a decade to kill the person who contracts it.

Women were the ones tasked with the preparation and cleaning of the bodies of loved ones (per Medical News Today). After the body was laid out, NPR reports that the brain was removed and cooked inside bamboo with some ferns. The rest of the body was fire-roasted and eaten as well. The men believed that eating the flesh of other humans would make them less able to perform in battle, so they largely abstained from the practice. Meanwhile, the women would eat the brain and the body, passing along little bits of what they had cooked to their young children. And if the loved one they were eating was infected with prions, it spelled a long, slow death for mother and child.

Funerary cannibalism is no longer practiced in Papua New Guinea

For more than 50 years, the ritual of funerary cannibalism has been halted among the Fore people of Papua New Guinea (per NPR). But though the practice of dining on the brain and flesh of dead relatives hasn't been a thing for a long time, it took decades before the ravages of kuru came to a full stop. Kuru is a condition that can progress so slowly that a person can be infected with it and not show a single symptom for years. Daily Medicos reports how there are three distinct stages of kuru, beginning with the shakes and tremors that gave it its name. From there, the stricken person experiences greatly diminished mobility and begins to lose control of their emotions. The final stage sends the body into ataxia, the inability to control even the smallest muscles. This can last for up to two years, with many dying from underlying causes during the third stage.

The last known death from kuru occurred in 2009 (per All That's Interesting). But the years of exposure to prions might have had at least one silver lining — the Fore people are now believed to be less susceptible to prion-related diseases based on genetic resistance (per The Washington Post). Today, the Fore tribe has doubled in size from the days when its villages were being ravaged by kuru. Now numbering more than 20,000 and growing, they still reside in the highlands of Papua New Guinea (per All That's Interesting).