Whatever Happened To Jack Greenberg From The Brown V. Board Of Education Court Case?

The 1952 Brown v. Board of Education lawsuit was a turning point for civil rights in the United States, and Jack Greenberg was one of the attorneys who argued the case before the Supreme Court. At 24 years old, he was the youngest lawyer Thurgood Marshall selected as part of his legal team, according to the Legal Defense Fund (LDF). One of the many important aspects of this case is that it recognized that school segregation was a nationwide issue, not simply a problem in southern states (via National Archives).

Segregation proved to be difficult even after the high court ordered all schools to desegregate immediately after Brown v. Board of Education. The Legal Defense Fund reports that the ruling was met with "massive resistance," creating a need for even more litigation across the country. And Greenberg was there to continue the fight for fairness, holding fast to his belief that civil rights were a "human cause," according to The New York Times.

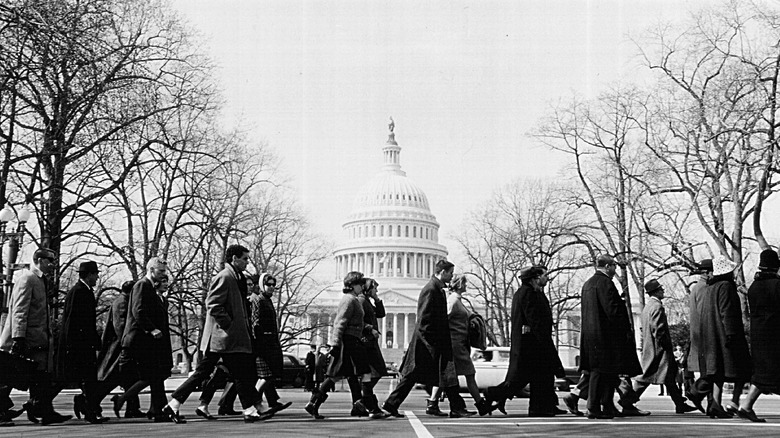

Free expression was at the heart of the Civil Rights Movement

After Brown v. Board of Education, school segregation had supposedly come to an end, but in many ways the problems were just beginning. Jack Greenberg became director-council of the National Association of the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF) in 1961 and began helping parents of Black children enroll their kids in schools. The LDF established the School Desegregation Task Force, which successfully managed to enroll some 4,000 black students in Southern schools by September 1965, reports the Thurgood Marshal Institute.

In a 1999 interview, Greenberg said (via Freedom Forum institute), "The civil rights movement featured various forms of free expression." And he was committed to fighting inside and outside the courtroom for everyone to experience the same freedoms. He explained in Richard Kluger's "Simple Justice: The History of Brown v. Board of Education and Black America's Struggle for Equality" that the fight was a "matter of human liberty," per Education Week.

Jack Greenberg argued other key cases

Jack Greenberg went on to argue in several other civil rights cases. In 1961, he successfully argued on behalf of James Meredith, who claimed he was denied admission to the University of Mississippi because of his race (via Civil Rights Litigation Clearinghouse). In 1971, Greenberg argued against racial discrimination in the workplace in the Griggs v. Duke Power Company. The case helped "eradicate arbitrary and artificial barriers to equal employment opportunity for all individuals, regardless of their race," per LDF.

Another segregation case he helped argue was Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education in 1969, in which the Supreme Court held that all schools must end segregation immediately (via Oyez). In a 2011 interview with Joseph Mosnier, Greenberg explains how he enjoyed working on the case, adding that it was an "example" of how the laws and all the legal documents in many cases are "interconnected." He also states that by the end of the civil rights movement, he and his fellow lawyers had represented 3,500 people and got them all acquitted.

He also fought for other human rights

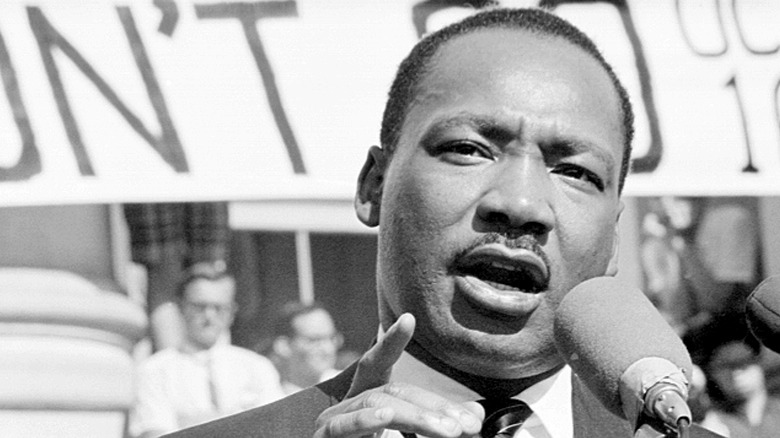

In 1963, Jack Greenberg was part of the team that defended Martin Luther King Jr. after he was jailed in Birmingham, Alabama. The lawsuit set the groundwork for another case that allowed people to march from Selma to Montgomery in 1965 (via The Atlantic). And that event led to the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which outlawed discriminatory voting methods, reports the LDF.

In 1972, Greenberg argued on behalf of William Furman, claiming the death penalty was cruel and unusual punishment that violated the Eighth and 14th Amendments. In this case, Furman's gun accidentally fired and killed a resident in the home he was burgling. The high court agreed, urging states and the federal legislatures to "rethink their statutes for capital offenses to assure that the death penalty would not be administered in a capricious or discriminatory manner," per Oyez.

He helped establish several human rights organizations

Knowing Jack Greenberg's passion for fairness, it shouldn't be too surprising that he also founded several organizations that fought for human rights. Aside from serving as director-counsel of the NAACP's LDF from 1961 to 1984, he also served on the board of directors for the New York City Legal Aid Society and the International League for Human Rights, according to the Digital Library of Georgia.

In 1967, he helped found the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund, an organization committed to protecting the civil rights of Latinos living in the United States. In the interview with Mosnier, Greenberg says he suggested to some Mexican-American lawyers that they take some cases, but there was no organization to help them, so he called a friend, got some money together, and set up the organization (via the Library of Congress). Greenberg also founded the Human Rights Internship Program at the Columbia Law School in 1984.

Jack Greenberg taught law and wrote several books

Jack Greenberg was also a teacher. The New York Times reports that he became a professor of law at Columbia University in 1984 after serving as an adjunct professor since 1970. He became dean of Columbia Law School from 1989 to 1993 and taught until 2015. He also worked for a time at Yale Law School in 1971 and the College of the City of New York in 1977.

Aside from teaching and practicing law, Greenberg found time to write. In 1994, he wrote a memoir called "Crusaders in the Courts: How a Dedicated Band of Lawyers Fought for the Civil Rights Revolution," where he describes his "moderate iconoclasm" from the standpoint of a Jew from the Bronx fighting for civil rights, reports the LDF. He also co-wrote a cookbook with Harvard Law School Dean James Vorenberg entitled "Dean Cuisine or The Liberated Man's Guide to Fine Cooking" (via Columbia University).