The Storied History Of Negro League Baseball

Though sadly largely fallen into obscurity, Negro League Baseball was once one of the biggest professional draws in the U.S. Forced to play in separate leagues from white players due to a lack of civil rights, Black players formed the earliest proto-versions of the Negro Leagues in the early 20th century (via History). Once established, they lasted for almost half a century, before finally succumbing to financial scarcity following Jackie Robinson's breaking of the color barrier in 1947.

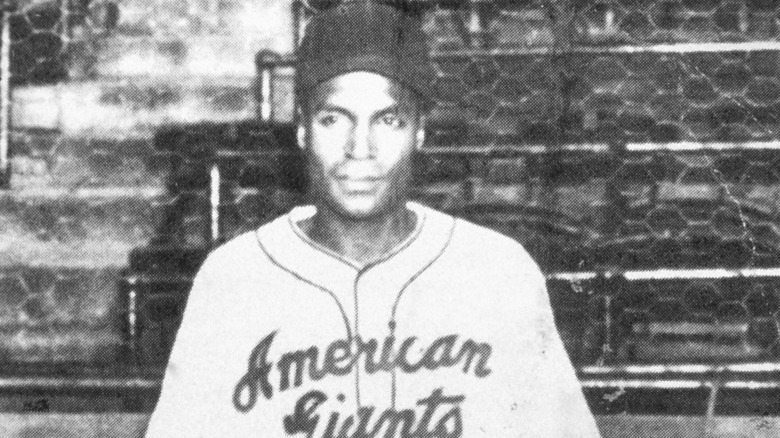

Still, decades later, the Negro Leagues are one of the most important and storied parts of professional baseball history. Teams like the Kansas City Monarchs, Homestead Greys, Chicago American Giants, and Birmingham Black Barons, entertained Black audiences for years (per MLB). They played top-notch baseball and produced some of the best players in history, proving generations of ignorant racists wrong and showing they truly belonged in Major League Baseball the whole time. This is the storied history of Negro League Baseball.

The Negro Leagues started due to racism

Though its origins are disputed, baseball is widely considered to have begun in the mid-19th century, less than a couple of decades before the Civil War (according to History). At first, baseball was slow to develop within the Black community — many of whom were still enslaved throughout the country prior to the Emancipation Proclamation (via History) — at least until the late 1850s, according to History. Following the war, Black baseball clubs were still largely segregated from playing against white teams, and the National Association of Amateur Base Ball Players refused to accept any Black teams into their ranks.

In 1884, Black catcher Moses Fleetwood Walker played a game in a proto-Major League Baseball league, and in the 1901 season, Charlie Grant almost broke the color line in Major League Baseball, per the Society for American Baseball Research. But racism prevented either from going any further, and further bolstering this racial prohibition was an informal "gentleman's agreement" among owners to not sign any Black players. Still, the game began to grow within the Black community, and they managed to find other circuits, like the International League, that would allow them to play.

However, by the 1890s, nearly all white professional leagues had completely closed their doors to Black players. While some tried to play in traveling leagues where they pretended to be Latin American, others began playing in several independent integrated and Black leagues. By the 1900s, efforts to start the first unofficial Black leagues were underway, and in 1903 the first "Colored Championship of the World" was played.

Rube Foster and the Negro National League

Though there were a few different independent baseball leagues that survived into the early 20th century, integrated and Black leagues formed during this period struggled to stay afloat and profitable. According to History, while some individual teams had the ability to regularly attract fans, actual leagues struggled to do the same. That started to change in 1920 with Black pitcher Rube Foster, who had originally been one of the best pitchers in Black baseball at the turn of the century, winning the 1903 "Colored Championship of the World" and pitching in four out of five games (per the Baseball Hall of Fame).

In 1920, Foster — then owner and manager of the Black baseball team the Chicago American Giants — created the Negro National League for Black teams. It was immediately a success and had eight teams participating, including the now legendary Kansas City Monarchs, Detroit Stars, and Indianapolis ABCs. The original Negro National League folded in 1931, but rebranded again to survive for another 15 years from 1933 to 1948.

In addition to Foster's league (both instances), there were several other professional Negro Leagues that were competing at the same time. These included the Eastern Colored League — which played Foster's league in the early Black World Series — as well as the American Negro League, Negro Southern League, and the Negro American League. In all, there are seven Negro Leagues that are considered to have been professional leagues, including those mentioned above, as well as the East-West League which was founded in 1932 (per the Associated Press).

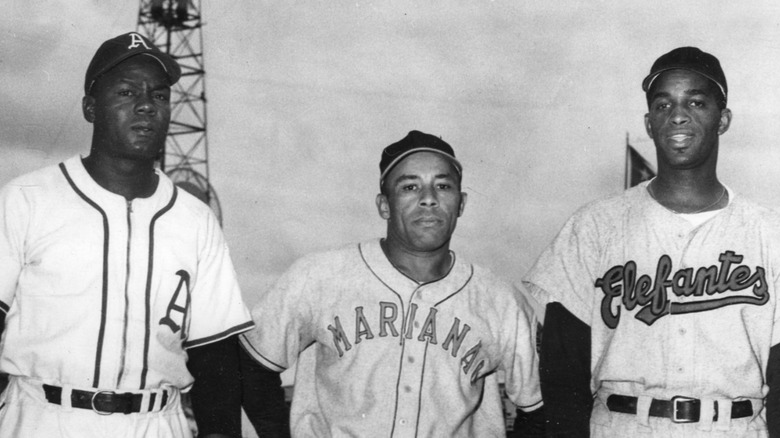

The Negro Leagues had some of the best players in history

While playing in Major League Baseball alongside their white counterparts was prohibited, per History, the Black players of the Negro League still proved that they could play the game of bat and ball just as well as anyone. Of all the Negro League players now immortalized long after their careers have ended, Leroy "Satchel" Paige might be the most well known. Paige became one of the best pitchers in Negro League history, dominating batters with his overpowering fastball when he was just barely out of school (per the Baseball Hall of Fame).

Adding to Paige's resume is the aura of myth that surrounds him. While he is only credited officially with pitching in 391 games and just shy of 1,700 innings, he used to boast that he had actually thrown closer to 2,500 games spanning his nearly four-decade career (per the Baseball Hall of Fame). Yet, Paige was far from the only Negro League star to be considered great.

Power-hitting catcher Josh Gibson is also thought to have been one of the best long-ball hitters in the game's history. Gibson is said to have once hit a home run 580 feet long, an absolutely jaw-dropping accomplishment, per the Baseball Hall of Fame, and has been favorably compared with legends like Babe Ruth and Ted Williams. Other highly accomplished Negro League players include pitcher "Smokey" Joe Williams, who used to throw so hard his team had to switch catchers halfway through games, per the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Integration and the decline of the Negro Leagues

In an unfortunate paradox, baseball's finest moment in the 1940s turned into the death knell for the Negro Leagues. In one of the game's most powerful and important moments in history, on April 15, 1947, Jackie Robinson officially broke the "gentleman's agreement" prohibiting Black players from playing in Major League Baseball (MLB), when he started for the Brooklyn Dodgers, as described in "Black Diamond: The Story of the Negro Baseball Leagues." This opened the path to MLB for many other Black players at the time, but it also spelled the end of the Negro Leagues.

After Robinson had success in his first games as a Dodger, other teams in MLB started to sign Black players. Yet, as more and more talented Negro Leaguers went to the newly integrated MLB, their former clubs struggled to retain audiences in their absence. Even worse, the Negro League teams were poorly compensated — if at all — for the departure of their star players.

By the end of the decade, the Negro National League folded for the second time, this one for good, and by the 1960s, the Negro Leagues were practically all finished (via History). Progress with civil rights allowed more Black players to play in MLB, but the transformation was not immediate. Within six years, less than half the teams had integrated, with the last holdout being the Boston Red Sox, who didn't do so until 1959.

The Negro League World Series

Denied a chance to play against white players in Major League Baseball, those in the Negro League still fielded a high level of competition between teams. And though it did not happen every year, there was also a World Series for Negro League baseball. According to the Center for Negro League Baseball Research, there were 11 Negro League World Series, held from 1924 to 1927, and again from 1942 to 1948. For the first four World Series, the best team in the first Negro National League played the best team in the Eastern Colored League. For the second stint of the World Series, the second Negro National League played the Negro American League.

The first Negro League World Series was held in October 1924 (pictured above), and saw the Kansas City Monarchs from Rube Foster's National League defeat Hilldale. The series lasted for nine games and was played in four different cities owing to scheduling difficulties (per the Negro League Baseball Museum). The only thing integrated about the series was the umpiring, which had both white and Black officials behind the dish.

Of the 11 Negro League World Series played, the Homestead Grays won the most with three victories. The Kansas City Monarchs were the only team to play in both versions of the World Series, both times as a National League team. They won one championship during each era, in 1924 and 1942.

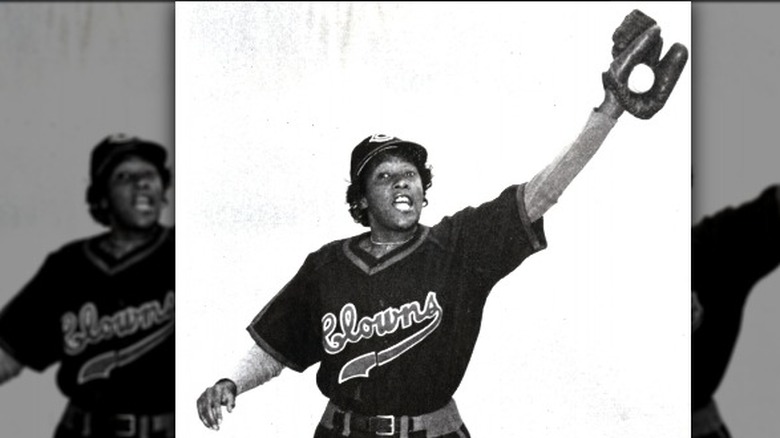

The women of the Negro Leagues

While it may seem like the men of the Negro Leagues get most of the attention, the women of the Negro Leagues played very important roles. One of the most famous was Effa Manley, a white businesswoman and longtime Negro League club owner. According to the Baseball Hall of Fame, Manley was a lifelong civil rights activist who purchased the Newark Eagles in 1935 with her husband, Abe Manley. In 1946, they won the Negro League World Series over the Kansas City Monarchs.

Once Major League Baseball (MLB) integrated in 1947, Manley's own fortunes as team owner declined, but she tried hard to bring equality to the Black players being signed to MLB. At the time, her efforts were wrongly portrayed as trying to stop Black players from joining MLB (via "Black Diamond: The Story of the Negro Baseball Leagues"). In reality, she wanted to guarantee fair pay and stop players and Negro League team owners from being taken advantage of.

In addition to club owners like Manley, there were also a few Black women who played ball in the Negro Leagues. From 1953-1954, the Indianapolis Clowns signed fielders Toni Stone, Connie Morgan, and pitcher Mamie "Peanut" Johnson to play in the Negro American League. Though they faced gender discrimination, they successfully attracted new audiences to the Indianapolis Clowns. They were also all good ball players, and Stone may have even gotten a hit off the legendary Leroy "Satchel" Paige (via the Baseball Hall of Fame).

The Negro Minor Leagues

Just like Major League Baseball has had its own minor leagues for many years, the Negro League also had an informal minor league system, too. According to MiLB, there were several leagues that served as unofficial minors for the Negro Leagues. These included the Negro Southern League, Texas Negro League, and Negro Midwest League. Though the Negro Southern League was also considered a major league at some points, and it was the first stop for eventual legends like Norman "Turkey" Stearnes and Leroy "Satchel" Paige.

There were also many barnstorming — traveling — teams that were essentially informal minor league teams without an official circuit. Many later Negro League players started out on barnstorming teams proving their skills, and some went back and forth depending on who offered the highest contract. Differentiating the barnstorming teams from the true minor league teams was their skill level, as the barnstormers were often considered on par with the major Negro Leagues.

As the Center for Negro League Baseball Research explains, the Negro "Minor" Leagues also helped Black audiences who did not have major Negro League teams they could watch. It also allowed Black players to showcase their skills while staying close to home, where they could still support their families at a time when baseball was not highly lucrative for most players — especially those in the Negro Leagues.

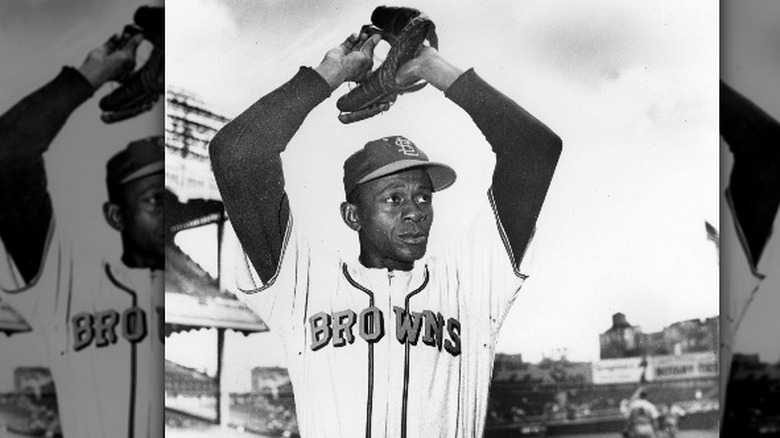

Many Negro League veterans made it to MLB

Among the most unfortunate legacies of the Negro Leagues are unanswered questions, namely what would have happened if the stars of the Negro Leagues had played in Major League Baseball (MLB). Would "Smokey" Joe Williams have blown his heater by Ty Cobb in the World Series? Could Josh Gibson have taken Hal Newhouser deep at the old Tiger Stadium in Detroit? Sadly, we'll never know the answer since these legends were prevented from competing against each other.

However, there were some Negro League legends that at least got a chance to shine while playing on the grand stage, like Leroy "Satchel" Paige, who played in MLB in the late-1940s. Though past his prime years, Satchel still helped the Cleveland Browns to win the 1948 World Series, and he also won two All-Star selections while on the team, too (per the Baseball Hall of Fame). He finally pitched his last game in MLB at the age of 59 after being retired for several years, throwing three scoreless innings against the Carl Yastrzemski-led Boston Red Sox.

Other famous Negro League players to make it to MLB included Larry Dobby, Ernie Banks, and Ray Dandridge, all Baseball Hall of Famers. Dandridge was well past his prime as an infielder in his late-'30s and never played above the minor leagues, but he still signed with the New York Giants and helped mentor future legend, Willie Mays.

The Negro Leagues in MLB's Hall of Fame

Though many Black players never got a chance to play on the field in Major League Baseball (MLB), that did not stop baseball from recognizing their immense contributions to the game — eventually. Starting back in 1971 with Leroy "Satchel" Paige, MLB has slowly begun to induct Negro League players into their Hall of Fame (via MLB). Unfortunately, progress has been somewhat slow, as there have only been 37 inductees from the Negro Leagues over the last 50 years, and some of them have been white owners and not players. Yet, at least some of the biggest stars have been given their proper dues.

Following Satchel's induction in 1971, Negro League legends Buck Leonard and Josh Gibson came the following year, and soon Monte Irvin, James "Cool Papa" Bell, and Rube Foster were on their way a few years later.

In 2006, MLB made a splash by inducting 17 new Negro League players into the Hall of Fame, including players Jud Wilson and Biz Mackey, as well as former Kansas City Monarchs owner J.L. Wilkinson, and former Newark Eagles owner Effa Manley (via The New York Times). Since 2006, only former players Buck O'Neil and Bud Fowler have been elected, but hopefully, there will be more on the way.

The 2008 MLB Draft of the Negro Leaguers

One of the most exciting moments for many ballplayers is the day they are drafted into the major leagues. And while the vast majority of Negro Leaguers never got the opportunity to be drafted by or play for a Major League Baseball (MLB) team, in 2008, the league symbolically acknowledged this injustice. That year, in addition to the First-Year Player Draft, every MLB team "drafted" a living former Negro League player (via ESPN).

None of the drafted players ever made it to MLB during their careers, and the idea was borne out of wanting to give surviving players their dues while they were still living. The draftees included brothers Charley and Mack Pride, who were selected by the Texas Rangers and Colorado Rockies. Also drafted was former Indianapolis Clowns female pitcher Mamie "Peanut" Johnson, who was picked by the Washington Nationals.

The oldest selection went to Puerto Rican baseball Hall of Famer Emilio "Millito" Navarro, who was 102 years old at the time of the draft (via MLB). He was selected by the New York Yankees, having played most of his actual career for the Cuban Stars.

MLB finally recognizes Negro League statistics

In addition to electing several players to the Hall of Fame and holding the symbolic 2008 First-Year Player draft to include them (via ESPN), Major League Baseball (MLB) made a huge step in embracing the Negro Leagues in 2020. That year, MLB started to add Negro League statistics to the official record books (per The New York Times). Previously, the only Negro League players who were allowed in MLB record books were those who played in MLB, and it was only their MLB statistics that were counted.

The change affected roughly 3,400 Negro League players, none of whom were eligible for entry before. Since there were several different Negro Leagues that operated from 1920 until integration in the late 1940s, MLB officially included only seven of them as eligible. However, even though MLB is making an effort to include as much as possible, the fragmented and erratic records from the Negro Leagues — some of which are a century old — make it tough to count everything accurately.

As such, many Negro Leaguers still have undercounted totals. This includes players like Josh Gibson, who is said to have hit nearly 800 home runs, yet is only credited with 165 officially (via Baseball Reference).

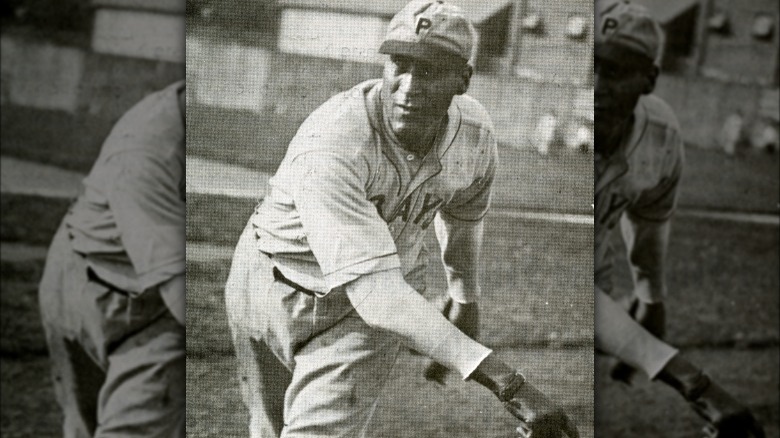

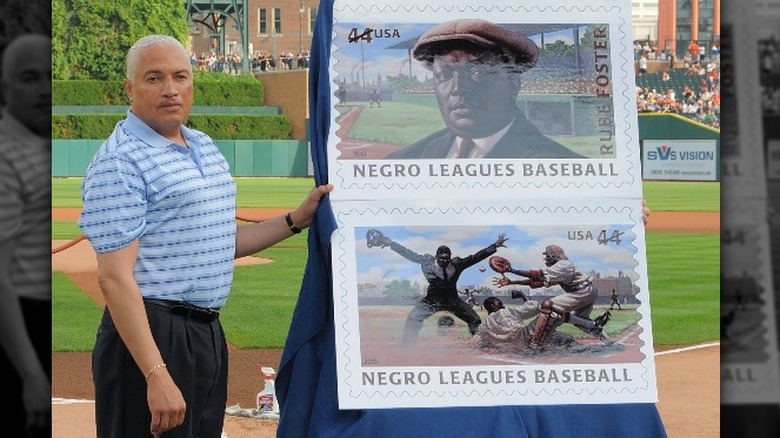

The Negro League commemorative stamps

Though it has gone largely unnoticed, on two separate occasions the U.S. Postal Service has commemorated Negro League players on stamps. The first time was in 2000, when they made stamps with the likenesses of Josh Gibson and Leroy "Satchel" Paige. The Gibson stamp had a portrait of him from his time playing for the Pittsburgh Crawfords, holding his longtime catcher's mitt while crouching in his catching position (via the Smithsonian National Postal Museum). Satchel's stamp features him in the uniform of the Kansas City Monarchs, while seemingly pitching from the stretch (via the Smithsonian). Both were 33-cent stamps.

In 2010, the U.S. Postal Service once again issued a commemorative Negro League stamp, this time with Rube Foster, the founder of the Negro National League, as the image (per the U.S. Postal Service). The stamp was released as part of the celebration for the 20th anniversary of the Negro League baseball museum. Altogether, the Postal Service has released at least 20 Negro League stamps, recognizing some of the best players in history.

The Negro League Museum

In 1990, the ultimate tribute to the Negro Leagues was created, when the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum first opened. Originally located inside a one-room office when it opened, the museum has since shifted to a huge complex in Kansas City, Missouri, home of the legendary former Kansas City Monarchs. It is recognized by the U.S. Congress as the official Negro League baseball museum. The current president of the museum is Bob Kendrick, and previously from the 1990s until his passing in 2006, it was former Negro League player Buck O'Neil (via The New York Times).

The museum boasts upwards of 60,000 visitors a year, and has had more than 2 million total since the museum opened. The museum is privately funded and non-profit, and is widely supported by Major League Baseball (MLB). Many MLB teams visit the museum when they travel to Kansas City to play the Royals, including the Los Angeles Dodgers, who visited in 2022 (via MLB). According to Forbes, the museum is only growing in popularity, and has flourished under the leadership of Kendrick.