Here's What Going To School Was Like In The U.S. In The 1800s

Education has changed immensely over the past few centuries. Back in Colonial times in the 1700s, education was a very informal affair, with parents doing a fair amount of teaching themselves. Proper schools weren't easy to set up because of geographical constraints, and even when they were up and running, many focused their teaching on religion and basic subjects like reading (per Encyclopedia).

According to Encyclopedia, girls' education lagged behind too, with many being taught how to read but little else beyond things like needlework, music, or drawing. Things started to slowly change as the 18th century came to a close, though formal schooling would not be properly set up in many states until the second half of the 19th century.

After the American Revolution, there was a major push by Congress to establish a public education system. According to a 1787 Ordinance for the government of the Territory of the United States northwest of the River Ohio (via Yale Law School), the education system was to "forever be encouraged," as it was deemed an essential part of "good government and the happiness of mankind." While Thomas Jefferson also pushed for public education, it wasn't until the early 19th century that an official public education system was finally put in place and education became a much more organized affair, according to the Public School Review. Here's what school was like in the 1800s.

Schools in the 1800s required lots of upkeep

According to The Heritage Alliance of Northeast Tennessee & Southwest Virginia, a typical school could be built of wood, stone, or brick. Some were covered in siding, while others were simpler structures. Some buildings even had a tower with a bell used to call children to class. Floors were usually wood, and students would often be in charge of oiling the floors to keep them in good condition. As students entered the building, a small area was dedicated to being used as a cloakroom, where coats and bags or their metal lunch boxes were kept. The room itself contained little except seats for the pupils, a raised structure where the teacher's desk was located, and a blackboard that covered the entire front wall (and sometimes part of the side walls). There was an outhouse behind the school and drinking water was taken from a well outdoors.

While urban schools were better supported, rural schools often depended on the community they served. Residents would provide firewood for the school's stove, help with supplies, and even build some of the furniture. Children only had basic supplies, including slate boards and chalk, for learning. Teachers themselves were even taken in by different families of their students sometimes, according to the Public School Review.

Subjects in school focused on the basics

As there was no structured teaching system or curriculum in place and not enough textbooks available, teaching in the 1800s focused on the basics. Most schools made reading, writing (including good penmanship), and math the focus of the school year, according to The Heritage Alliance of Northeast Tennessee & Southwest Virginia. This is still known today as the three "Rs" of basic skills-oriented education: "reading, 'riting, and 'rithmetic."

Recitation (sometimes called "the fourth R") was a big part of teaching reading, with students having to memorize long passages that they would then repeat in front of the class. School would often start with children taking turns to recite (or sometimes read) from a book. Writing was practiced on slate tablets.

A popular arithmetic textbook was published in 1821, but before then, teachers would often repeat basic math rules that needed to be memorized even if they were meaningless to new students. With the publication of Warren Colburn's First Lessons in Arithmetic in 1821, a new system to teach math was put in place to help younger children understand the concept of numbers. This was done via basic techniques like counting beans or buttons long before students were introduced to abstract things like plus and minus signs (per the University of Georgia).

Days at school were long

School-age children spent a large part of their day at school, often starting at 8 or 9 a.m. and not going home until 3 or 4 p.m. However, their days usually started much earlier than that. Without public transportation in place (or for those too young to ride a pony), some children had to walk up to three miles to cover the distance between home and school (via The Heritage Alliance of Northeast Tennessee & Southwest Virginia). Older students sometimes arrived even earlier to help teachers set up the classroom and get the wood stove going. Students would wait to enter the classroom until everybody had arrived or it was time to start. At that point, they would separate into two groups, with girls entering first.

The official beginning of the school day included formally saying good morning to the teacher and then reciting both the Pledge of Allegiance and the Lord's Prayer. In some schools, this was even followed by reading from the Bible. Students had lunch and recreational breaks throughout the day, and some would stay after school — either as punishment for misbehaving during the day or to help clean up the room and wash the floors.

The school year was either a lot shorter or longer than today

While today's school year may seem long, students only attend school for around 180 days because of breaks and official bank holidays throughout the year. This means students spend much of winter in school but have a big part of summer free, as reported via the Journal of Inquiry & Action in Education.

Back in the early and mid-1800s, the school year was significantly shorter in rural areas: an average of about 132 days or around 4 1/2 months. Even then, rural students often missed school, and the attendance rate was barely 59%, which meant students in the 1870s might only be in school about 78 days a year, according to the U.S. Department of Education. Many of the missing school days were connected to farm work, as children needed to take time off to help during the harvest season. Plus, poor healthcare and hygiene at the time meant children got sick often and had to stay home. Things started to change when states like Massachusetts passed compulsory school attendance laws in 1852. But farm kids were still often absent in spring and fall.

Punishment was hands-on

With an overcrowded classroom filled with children of all ages, teachers often resorted to physical punishment to stay in control in the 1800s. This often included spankings with sticks and whipping students with long rulers. Students were also forced to write sentences hundreds of times, memorize stories and recite them error-free, clean floors, and stand for long periods of time with their noses touching the blackboard, according to The Heritage Alliance of Northeast Tennessee & Southwest Virginia.

The dunce cap was also used in U.S. schools in the 1800s as a punishment tool. Although Merriam-Webster describes dunce caps as "a conical cap formerly used as a punishment for slow learners at school," it seems teachers were more likely to use it as a punishment for poor behavior. Disruptive and unruly children would be told to wear the cone-shaped hat and sometimes would need to stand in a corner for a period of time (per Hats and Headwear around the World: A Cultural Encyclopedia).

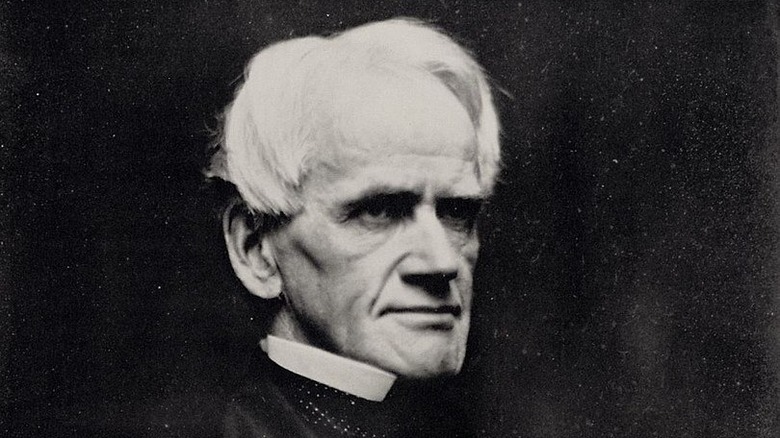

While rural schools continued using corporal punishment for many years, cities were starting to move away from it as early as the 1820s, according to the Journal of the Early Republic. At the time, schools were still regularly using rods, birch branches, and even whipping as a way to exert control over their classes. American educational reformer Horace Mann was instrumental in fighting against corporal punishment in schools in the 19th century, arguing that this repressed rather than reformed students.

Education for boys and girls wasn't the same

Up until the late 18th century, girls were often educated at home. While boys were learning additional academic subjects like math and logic in private schools, girls' education focused on things like sewing, fine penmanship, needlework, and art — all things that would make them better wives, mothers, and women in society (via Florence Griswold Museum). According to "Women's Education in the United States, 1780-1840," (via History of Education Quarterly), women tended to receive an education based on "ornamental courses" while men received "useful courses.

Things improved significantly for girls in the 19th century, with many towns opening girls-only schools led by better-educated female teachers eager to pass on their knowledge. As public schools became more commonplace, so did the enrollment of girls in those schools. By the second half of the 19th century, the Center for Education Statistics points out that enrollment rates in school were roughly even between boys and girls.

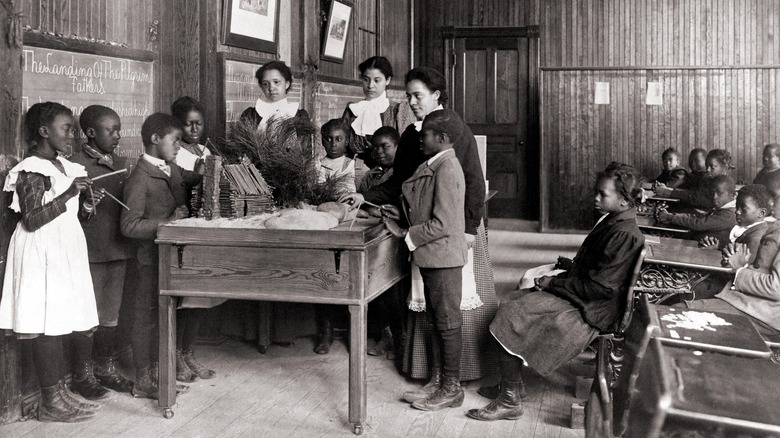

Schools for Black students were scarce

Education for African Americans in the 1800s was, at best, really complicated. Before the Civil War, Black people in southern states weren't allowed to attend school and most were not even able to read or write unless they were self-taught (via Center for Education Statistics). Even in northern states, though, where they were technically allowed to receive an education, access to it was very limited before the 1860s. After the Civil War ended in 1865, things improved quickly. By 1870, 10% of Blacks were enrolled in school, and by 1880, 34% were.

Much of the change was due to the work of the U.S. Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (or Freedman's Bureau), which helped former slaves transition into society after 1865. This included everything from relief work to medical aid and helping settle disputes. But their most important work was done in the field of education. In fact, the Bureau oversaw the opening of over 1,000 schools for Black students.

In the south, where resistance to accepting former slaves integrating into society was stronger, the Bureau was even more active. Their Freedman's Union Industrial School operated in Virginia was key to helping Black students learn the basics of reading and mathematics, but also a trade that would help them find a job. By the end of 1865, about eight months after the war ended, more than 90,000 former slaves were attending schools set up by the Bureau (per Digital History).

Native Americans were abused in boarding schools

As it had since its founding, the U.S. government spent much of the 1800s waging war against Native Americans. By the 1860s, when the Union Army was fighting for the end of slavery, Natives were being imprisoned, killed, and persecuted around the country (via Library of Congress).

But there was also another war taking place on the education front, supported by something called The 1819 Civilization Fund Act, the main focus of which was to educate the Indigenous population to help "kill the Indian in him, and save the man," according to The Indigenous Foundation. Children were separated from their families and taken to 357 Native American boarding schools that opened up across the country in 1860.

One goal of these schools was to eliminate Indigenous history and identity by giving children Anglo-American names and forcing them to convert to Christianity. The other was educating them not only in basic subjects like reading, writing, history, and math but also teaching them a trade, like blacksmithing for boys and cooking for girls. While these seem useful enough, children were then often placed in "programs" where they would be exploited as free or cheap labor using those skills.

According to The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, boarding schools (many of which were run by the church) were involved in sexual and extreme physical abuse towards these children. Many disappeared after being in boarding school and were never returned to their homeland.

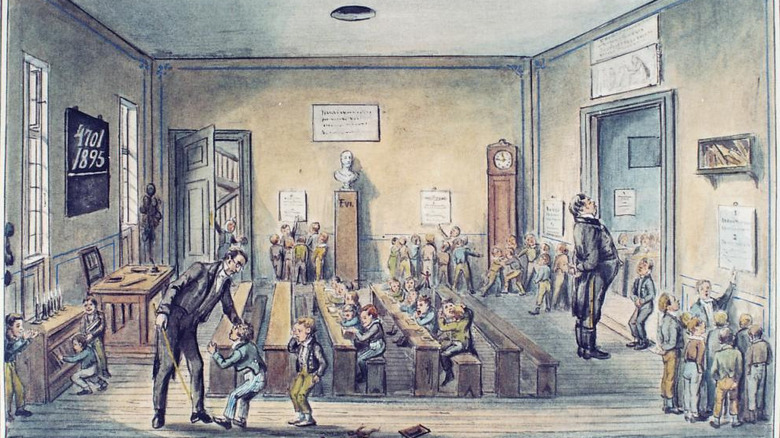

Early schools used a monitorial system

Also known as the Lancasterian system, the monitorial system was meant to take some of the pressure off teachers. With teachers often taking on quite large classes to make up for the lack of available educators, older children were assigned some of the classroom duties (per History). Under this system, teachers would only teach new concepts to older students or those who were performing better academically (regardless of their age).

These students would then in turn teach the younger ones, but also sometimes take attendance, test students to see if they could be promoted to a different class, or even take care of preparing materials for the classroom. This freed up time and resources and allowed teachers to focus on organizing and overseeing the classroom instead of teaching the same things over and over.

Although unusual, the system did have some benefits. For example, it allowed schools to operate even if there was an issue finding enough teachers, and it also eliminated waiting time. If a single teacher had to teach different subjects at different levels to a big class, many students would have to wait their turn, wasting precious time. With older children involved in the teaching process, everybody was always actively involved in the learning process (via Britannica).

Horace Mann changed the school system

Enter Horace Mann, who took over as secretary of education of Massachusetts in 1837. Mann used what he had learned observing the European school system to transform the one in the U.S., including requiring examinations for teachers to ensure their competency. By the midpoint of the century, Mann's methods had begun to spread across the country.

Mann, often called "the founder of the U.S. public school system," advocated for state-supported schools, a unified curriculum, properly set up school buildings, and free public education for all. Another major change from the previous century was the introduction of "normal schools" — basically, a two-year college-level education to prepare teachers to lead a classroom. Before these schools were put in place, teachers were adults (mostly women) willing to teach but without any formal education or the tools needed to properly instruct children. The first private normal school opened in 1823, but by 1839, public normal schools were starting to open as well (per Buffalo State University).

The second half of the 19th century brought along many changes

There were significant educational changes in the second half of the 19th century, which not only improved education in general but also opened the door to many new things.

A big one was the introduction of kindergartens in 1856, following the example of Germany. Until then, children started school straight into first grade and immediately focused on learning the same subjects as older students. Kindergarten was a great addition that allowed more creative activities to stimulate the mind (per Library of Congress). Although the first kindergartens were private, free public ones were available in 1873. They were a major success in helping children improve manners and speech and learn self-control and social skills (per VCU Libraries' Social Welfare History Project).

In the 1890s, another major change took place in schools with the introduction of physical education. As noted by the Library of Congress, this was a major step forward not only because it helped recognize the importance of team sports and exercise, but also because it was available for both boys and girls (and the latter had been ignored for certain school activities throughout the century).