How Madame Tussaud Built An Empire Out Of Wax

Known best for real-as-life wax sculptures of Hollywood actors, pop stars, and American presidents, Madame Tussauds actually has a dark and macabre history that goes all the way back to 18th century France, when ridiculously giant wigs were fashion-forward and watching executions was a national pastime.

Madame Tussaud was one of the worlds' first female entrepreneurs. She was an artist, a businesswoman, a PR genius, and most probably a liar (but PR geniuses sort of have to be). Her fame probably had more to do with death masks, torture devices, and crime scene dioramas than with the fine craftsmanship of her wax likenesses, but Tussaud never seemed to mind. From its unpretentious beginnings as a traveling exhibition, Madame Tussauds waxworks grew into an empire — today you can visit Madame Tussauds in dozens of cities all over the world. And while Tussauds is unlikely to ever abandon its bloody roots, it does have something for everyone. If the Chamber of Horrors just isn't your thing, you can always take a selfie with Benedict Cumberbatch instead. We won't judge.

A noble tradition of horrible, horrible, death

Madame Tussaud was born Anna-Maria Grosholtz in December of 1761. Her father was a public executioner, who came from a long line of public executioners, because apparently that was a profession passed down from father to son like being a carpenter or a doctor. Imagine having to sell your wants-to-go-to-art-school teenager on that one. "No son, we come from a time-honored family tradition of chopping people's heads off. I'm not paying for art school."

Anyway, Joseph Grosholtz did not live to see the birth of his daughter, so was unable to pass his noble tradition off to anyone. According to one story, he fought in the Seven Years War and died two months before Tussaud was born. And because nothing about Madame Tussaud's life can be free from gruesome horror, History Today has made sure to provide us with the especially gory details of her father's death: Just before he died he lost his entire lower jaw in battle, and had to have it replaced with a silver plate. Evidently the surgery was not only horribly disfiguring but also not very successful. Anna-Marie's widowed mother, Anne Marie Grosholtz, was left alone with a newborn and a desperate need to find employment.

Sure, they're for medical research. Uh-huh.

According to Henry Poole, Anne Marie obtained a housekeeping position with a Swiss physician named Philippe Curtius, because in those days housekeeping was like the number one legitimate career path for widowed women, and she really didn't have a ton of alternatives.

Anne Marie's choice of employer turned out to be prophetic for her daughter. Besides making house calls, Curtius also spent his time building anatomically-correct wax models, which were supposedly meant as medical research tools, but also attracted a lot of non-professional attention. The king's cousin, for example, commissioned him to create erotic wax figures for a salon on the Rue Saint-Honore, so the young Tussaud was probably exposed to some stuff that would make most moms of the day shriek in scandalized horror and clap their hands over their kids' eyes.

By 1774, Curtius had moved up from "medical research" tools to wax figures of famous people, including King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. Tussaud became his apprentice, and eventually came to think of Curtius not just as a mentor but as an "uncle."

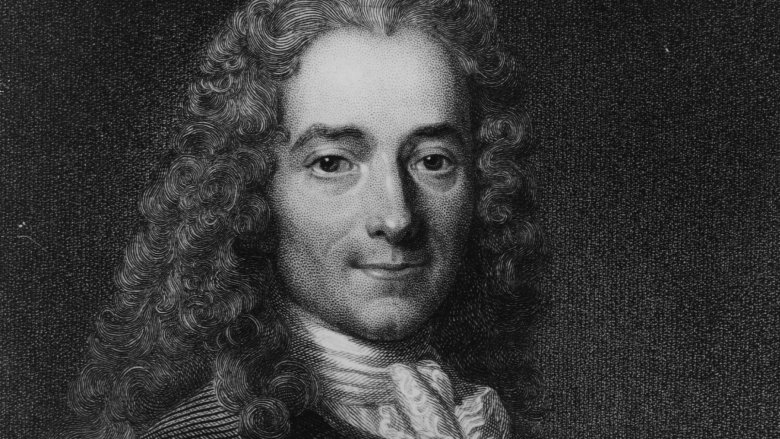

She hung out with Voltaire. Probably.

Cutius's fame as a wax sculptor attracted the attention of the upper class, which meant that Tussaud got to mingle with a lot of famous — and infamous — figures. At a very young age, she was introduced to French philosopher and writer Francois Voltaire, who was usually just called "Voltaire" because exceedingly cool people are only ever allowed to have one name.

In 1777 Tussaud chose Voltaire as the subject of her first wax portrait, just one year before his death. There have been some rumors that she also made Voltaire's death mask, but John Theodore Tussaud, Madame Tussaud's great-grandson, wrote that the death mask part of his grandmother's career didn't begin until the French Revolution, which was more than a decade after Voltaire died.

A wax sculpture of Voltaire is on display at the Madame Tussauds museum in London, but it's not the one made by 16-year-old Marie. In fact there's some evidence that the original was just done for practice, and might have eventually ended up out back in a trash bin. Imagine dumpster diving in that neighborhood.

Yeah, I worked at the palace. It was okay.

Madame Tussaud was skilled in the art of wax sculpture and probably also pretty skilled in the art of BS. Her memoirs are full of questionable stories — the kind of stuff Bob at the office is always bragging about while everyone at the water cooler clandestinely rolls their eyes. "Yeah," says Bob, "I knew Voltaire. I also taught art to royalty. You should come over and look at my paintings sometime." Sure, Bob.

In her memoirs, Tussaud claimed to have lived at the Palace of Versailles, where she worked as an art tutor for King Louis XVI's sister Madame Elizabeth. But there's really not any proof that this ever happened — Journal18, a peer-reviewed eighteenth-century art history journal, calls the claim "questionable." And Henry Poole notes that Tussaud was "a great self-publicist," so it's possible — and maybe even likely — that she made up the story so her memoirs would be a little bit more colorful. Nevertheless, her years at Versailles (whether they actually happened or not) have been pretty widely included in nearly every biography written about her, so they're an important part of her story even if they aren't 100 percent true. Or even 1 percent true.

She may or may not have been almost executed

The French Revolution began in the summer of 1789. According to The Vintage News, just days before the revolution began in earnest, an angry mob descended on Paris. Someone said, roughly, "What we really need is royal heads to parade around town on pikes." And someone else said, more or less, "Hey, I heard that wax model-making lady has some fake ones!" And everyone went, basically, "Huzzah!" and they decapitated a couple of wax royals and paraded them around town on pikes. It probably lost a little something without the blood and gore of a real severed head, but they were a very practical angry mob, so they just made do.

That must have been a little unnerving for Tussaud, who may or may not have once lived with the royal family. And eventually the revolutionaries did decide she sympathized with the royals and threw her in a dungeon, shaved her head, and told her to make ready for the executioner.

Fortunately, word of Tussaud's skills as a wax modeler reached the right person, and she was released on condition that she take a job as a death mask maker, which falls just above crime-scene-cleaner-upper as most sucky occupation of all time. She did a pretty brisk business, though, making death masks from the decapitated heads of such notables as Marie Antoinette, Louis XVI, and her allegedly former art student Madame Elizabeth. Of course this information came directly out of Tussaud's memoirs, so feel free not to believe any of it.

On the road with Madame du Barry, Napoleon, and Marie Antoinette's head

According to Mental Floss, Marie Grosholtz married Francois Tussaud in 1795. Five years later she was all, "This dude is a deadbeat, why did I marry him again?" So she abandoned her husband and one of her two sons so she could take her gross little art project on the road. Now depending on your interpretation, those are either the actions of an ambitious woman (a persona that was vanishingly rare in the 18th century) who paved the way for entrepreneurial women of the future, or the actions of a seriously crappy mother. Really, it was probably a little of both.

Tussaud never saw her husband again — but thanks to her, his name became pretty famous anyway. That probably was not a huge comfort to him as he died penniless and alone, but at least it was something. Madame Tussaud also wasn't reunited with her younger son until 20 years after she left him. In the meantime, her macabre collection of wax murderers, severed heads, and other charming artifacts like iron maidens and guillotines became notoriously famous — so famous she was eventually able to build a permanent museum on Baker Street in London, which is not very far from where fictional Sherlock Holmes lives. Today, Madame Tussauds is still in the same neighborhood, but if you can't make it to London there are 23 other locations worldwide, from America to Australia.

Let's just skip the lame celebrities and go straight for the chamber of horrors

Hollywood figured out a long time ago that humans love blood and violence, as long as it's happening to someone else. Eighteenth century people knew that too, but it wasn't proper to say so out loud unless you were standing around the guillotine with whatever the 18th century version of popcorn was. If Tussaud's experience during the French Revolution taught her anything, it was this: the dark side of human nature is a powerful force, and also it can be exploited for cash.

Tussaud's most popular attractions weren't the lifelike wax models of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. They were the deathlike wax models of their severed heads. Tussaud was a practical woman, so she happily catered to the lowest common denominator by setting aside a separate room where visitors could pay an extra sixpence to see severed heads alongside wax models of infamous criminals. According to National Geographic, as the Chamber of Horrors' popularity grew, the museum added crime scene dioramas and other terrifying artifacts, like the actual pram police used to collect and transport the dismembered victims of a notorious 1890 murder.

Today, the Chamber of Horrors is still a thing, which should come as no surprise since The Walking Dead is also still a thing, but it has expanded to include live actors who jump out of dark hallways and scare the crap out of everyone. Oh, what fun.

The time Madame Tussaud's bombed

War separates husbands from wives, parents from children, heads from torsos, and lower jaws from upper jaws. It can also take its toll on buildings and wax sculptures.

According to West End at War, on September 9, 1940, a German bomb struck near Madame Tussauds, one of many that fell during the event that would come to be known as "The London Blitz." The bombing destroyed 352 head molds, along with many of the waxwork figures and the entire Tussauds Cinema, which had been built in 1925, shortly after a fire took out an earlier version of the museum. A local reporter described "a macabre joke, stepping over wax arms and torn wax torsos," and then went on to express remorse that the wax model of Adolf Hitler appeared almost entirely intact. Which you'll find a lot more amusing by the time you get to the end of this article.

The museum was restored and remodeled, and a planetarium was added, though it's unclear how many severed heads were up there with all the stars and planets in those early days. The new addition did prove to be a boon, though, so maybe bombs are occasionally useful, especially when you've built your whole reputation around mayhem and destruction.

Horrible, horrible death finally comes for Marie. In her sleep.

Marie Tussaud was shadowed by death and horror her whole life, though it might be more accurate to say she was the one doing the shadowing. According to the Vintage News, citing Tussaud's memoirs, she would often dig through the piles of severed heads that were deliberately left to rot in public squares during the French Revolution – you know, so she could make death masks out of the best ones.

Most people don't deserve to die unpleasantly, but for Tussaud a weird, gloomy death would have been pretty poetic. Instead, though, she died in the most totally boring way possible — in her sleep.

It was only relatively recently that anyone thought to question her sons' account of her death — they said she was still greeting visitors just days before her sleepy demise. Over the years, though, we've learned to be skeptical of the things said by Tussauds.

One of her sons noted symptoms in a letter, and researchers believe they point to cardiorespiratory disease as a cause of death, or a progressive lung disease such as emphysema or chronic bronchitis.Other sources seem to suggest that her final illness lasted a few days, so although she may have actually died in her sleep, it might not have been the peaceful farewell we all hope for. Still, there was no beheading involved, and no pram was required for removing dismembered body parts, so on a scale of one to horrific, Tussaud went pretty easily.

Self portrait with severed head

In 1842, eight years before her death, Madame Tussaud made a wax self-portrait, which is still on display in the London museum. It's not the only portrait of Tussaud that exists — the best one is in Berlin, where Tussaud is portrayed holding the severed head of Benjamin Franklin. What, you didn't know Benjamin Franklin died by guillotine? That's because he didn't. The "severed head" portrait is actually meant to depict Madame Tussaud at work on a wax model, but it's just cooler to call it a severed head. Sadly, that model is not a Tussaud original.

Several of Tussaud's actual creations have survived, including the death masks from the French Revolution, and the French Royal family. Some models have been recast from the same molds used to make the originals, though they are not themselves original. According to the Jane Austen center, the oldest surviving sculpture is one of Philippe Curtius's — Kng Louis XV's mistress Madame Du Barry, also known as "Sleeping Beauty." Much of what you'll find at a modern Tussauds are models that appeal to a 21st century audience, such as Johnny Depp and Benedict Cumberbatch. Though you can still go into the Chamber of Horrors and get chased around by actors, if that's your thing.

Let's kill [wax] Hitler

Once he was a master orator, purveyor of the stupid mustache, and all around embodiment of evil. Today he's been reduced to a conversation piece for drunken philosophers. "If you could go back in time and decapitate Adolf Hitler, would you?" "Sure, but first give me another beer."

According to Time, a retired policeman identified only as Frank L. didn't bother to actually answer that question, he just went and did it. Of course without an actual TARDIS the only Hitler he had access to was the one at Madame Tussaud's. You might be able to see where this is headed. Or, uh, be-headed. Sorry.

On a summer day in 2008, Frank L. pushed his way past security at Madame Tussaud's in Berlin, tackled wax Hitler, and pulled his head off. Unsurprisingly, most people were cool with that. Commentators, eye-witnesses, and even the police exuberantly praised the attack as the first successful assassination attempt against Hitler. Undeterred, Tussaud's returned wax Hitler just a few weeks later, because some centuries-old waxwork museums never learn. Or they do, but they just love a good beheading.