Misconceptions About The Matrix You Probably Believed

"You've been living in a dream world, Neo." When Morpheus spoke those words to Neo in 1999, no-one could've predicted how insanely influential they would become. Neo's awakening from the Matrix, and the public awakening from the prison of cruddy late '90s sci-fi blockbusters (cough, The Phantom Menace, cough), is now recognized as one of the defining moments in modern cinema. The Matrix is so well known that even if you're the sort of viewer who usually prefers six-hour black and white silent Hungarian art house epics about the difficulties of preparing goulash in midwinter, you probably know all about it.

At least, you probably think you do. But what if everything you think you know is a lie? What if it turned out you were living in a dream world — a matrix, if you will — in which everything you thought you knew about your favorite philosophical action film was merely a clever construct maintained by human ignorance? Time to swallow that red pill marked "keep reading" and reveal things as they really are.

The machines are the bad guys

They enslaved humanity, turned them into batteries, and stuck them in a miserable cyberpunk dystopia where it's always 1999 and everyone works in offices that would give Dilbert nightmares. Seen in black and white like that it seems clear the machines in The Matrix are the bad guys. But that's a simplistic reading. In Matrix lore, the machines have every right to abuse humans.

The Animatrix was a collection of nine animated shorts released in 2003 to flesh out the world of The Matrix. Produced by the Wachowskis, it's part of the Matrix canon. Two of those shorts, parts I and II of The Second Renaissance, show how humanity invented artificial intelligence in the early 21st century. They also show how humanity enslaved these sentient machines, murdered them with impunity, and then tried to wipe them out in a nuclear holocaust when they demanded equal rights. Yep, the backstory to The Matrix is essentially a slave rebellion.

But that all takes place in other media! In the main trilogy itself, the machines are the obvious antagonists, right? Only if you ignore that whole speech the Architect gives at the end of Reloaded (and who could blame you). The Architect explains how the Matrix was originally created to be a perfect world that only got sucky because humans were too pessimistic to accept happiness. (See this Matrix blog.) What kind of bad guys try to create a paradise for their victims? Misunderstood ones, that's who.

Everyone hated the sequels

Matrix Reloaded and Revolutions occupy a special place in geekdom, one equivalent to the irradiated remains of Chernobyl if Chernobyl had been powered by disappointment and broken dreams. Geek site io9 has declared them a bigger letdown than The Phantom Menace. Their suckiness is now so accepted that it's assumed that audiences always hated them. Sad as it is to admit, that's not quite true. Look back at reviews from 2003 and it's clear a lot of influential people thought Reloaded was better than the original.

Roger Ebert was one of those people. His Reloaded review gave it 3.5 stars out of 4, which is half a star more than he gave the original. (Revolutions dropped to 3 stars, and Ebert admitted on reflection that the original was the best.) According to Rotten Tomatoes, Richard Roeper didn't just like Reloaded, he claimed it "soars to places only hinted at in the original." Critics at Salon, New York Observer, and New York Magazine all gave Reloaded superlative praise.

And it wasn't just critics. Cinemascore has been polling audiences outside movie theaters since 1978. Theater audiences gave Matrix Reloaded a B+, compared to the original's A-. So what gives? Well, you can probably blame hype for the inflated scores. Cinemascore also records an A- for The Phantom Menace, and you'd be hard pressed to find anyone today who considers it equal to The Matrix.

It's an allegory for Christianity or Buddhism

The Matrix mixed in so many different strands of religion that you've probably heard it called an allegory for Christianity, Buddhism, and even Hinduism. The one thing you probably haven't heard it called is a transgender coming-out fable. Well buckle up, 'cause that's about to change.

If you're thinking this sounds like zeitgeisty bunkum, have faith. This theory goes deeper than your average bong-inspired gender studies paper. The Wachowskis are both transgender. Lana came out in 2008, and Lily came out in 2016 (via Variety). The first film is stuffed full of little clues to their transgenderism, the biggest of which are all covered at geek site The Mary Sue.

The Matrix is about Neo, who is forced to publicly live as a guy called Thomas Anderson. Agent Smith keeps referring to him as "Mr. Anderson," even after he's transitioned into being Neo, a phenomenon the trans community refers to as deadnaming. While that's hardly conclusive, there are also crucial ties to Lana's life. As a teenager, she tried to commit suicide over her gender identity by jumping under a subway train. If you're not now thinking of Keanu Reeves growling "My name is ... NEO!" and spectacularly escaping death on a subway line, you're not making the obvious connection.

Then there's the fact that Switch's character was originally meant to be female in the Matrix, but male in the real world (via Tor). That would've made the subtext just text.

Bullet time came out of nowhere

Remember when you first saw The Matrix? The moment you got hooked was probably when you first saw bullet time, as Trinity leaped up in the air, froze as the camera swung around, then kicked the innards outta some poor cop. It was something that just hadn't been seen in cinema before. While it's pretty standard for action films to slow down, speed up, and sweep around fast-moving objects at impossible speeds now, in 1999 it was like watching someone reinvent the wheel. With bullets. Or it would've been, had others not already done something similar beforehand.

To be clear, bullet time itself was a completely new technique, created for The Matrix and never used anywhere else beforehand. But it's a myth that it came completely out of nowhere. Matrix VFX supervisor John Gaeta has said that bullet time was built on techniques pioneered by other directors (via Indiewire). Specifically, he credited Akira director Otomo Katsuhiro and Michel Gondry for inspiring him. Gondry in particular should probably get most of the credit here. Just check out his 1996 Smirnoff commercial (above) that opens with a Matrix parody done three years before The Matrix came out. Either the Eternal Sunshine director can add "psychic" to his long list of abilities, or bullet time wasn't quite as original as we thought it was.

The main inspiration was Ghost in the Shell

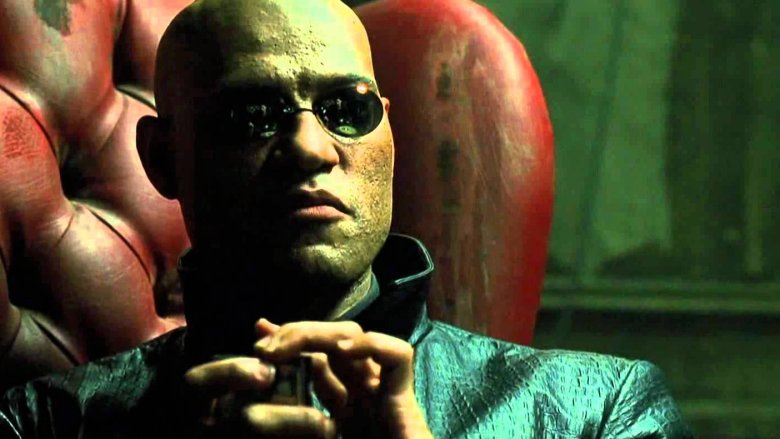

Ghost in the Shell was a groundbreaking 1995 anime movie by Mamoru Oshii that mixed philosophy with action in a cyberpunk dystopia where characters are constantly questioning the nature of their reality. If that sounds familiar, that's not surprising. Ghost in the Shell's influence on The Matrix is so well documented that Oshii declared in 2009 that he was fed up with answering questions about it (via The Guardian). At least everyone is aware of his influence on the Wachowskis. Graphic novelist Grant Morrison has never been acknowledged, despite his work probably inspiring The Matrix more than Ghost in the Shell.

Morrison's claim comes in the form of The Invisibles, a DC series that ran from 1994 to 2000. In it a group of rebels discover reality is an illusion and the human race has been enslaved by aliens. They recruit a regular guy who turns out to be a messiah figure who can alter reality and lead a kung-fu-and-guns rebellion, all while dressing in leather and wearing suspiciously familiar sunglasses. Oh, and the leader of their group, a guy called King Mob, just happens to look a whole lot like a paler version of Morpheus.

The Wachowskis have never acknowledged the influence of The Invisibles. However, they are both comics fans who once asked Morrison to write for them, so it seems likely they were aware of the series. Morrison has even claimed copies of The Invisibles were handed around on set.

Everyone agreed it was revolutionary

We like film histories to be simple and straightforward. It's much easier to read "audiences at the time were amazed by The Matrix's revolutionary techniques" than to delve through a complicated paragraph explaining how it initially didn't make much of a splash, but over time had enough of an effect on trendsetters and other artists to significantly change the way things are done. All of which might be why we tend to hear retrospectives talking about how The Matrix blew 1999 audiences away and immediately revolutionized the action movie. There's just one problem. In the spring of '99, it wasn't at all clear that was what had happened.

Go back and read the reviews again. A whole lotta critics seemed to think the film had an interesting premise but totally wasted it. Time Out dubbed it "another slice of overlong, high concept hokum." Roger Ebert said it was "fun, but it could have been more" and unfavorably compared it to 1998's Dark City. (In 2005 he would even write Dark City "did what "The Matrix" wanted to do, earlier and with more feeling.") The New Yorker's critic basically dismissed it.

Maybe it's because The Matrix was just meant to be the warm up to the summer's main event. In mid-May, the first Star Wars movie in 16 years was due to hit screens and blow everyone away. When that, uh, failed to happen, The Matrix probably began to look a whole lot more interesting.

It was the Wachowskis' first success

Before The Matrix, the Wachowskis were about as obscure as anyone working within the Hollywood studio system can be. After 1999, they briefly became the most famous directors on Earth. But the duo didn't come out of nowhere. They'd previously made one other film, 1996's Bound, a lesbian crime caper often overlooked today. Not that Bound was a dud, or even forgettable. While it failed to set the box office alight, earning back only half of its $6 million budget, it did better with the critics. In fact, it did so well that the Wachowskis were touted as the next Coen Brothers.

To give some idea of how popular Bound was in reviewing circles, check out this write-up by Roger Ebert. He sounds like he's just seen Citizen Kane for the first time, and he wasn't the only one. Bound picked up a slew of indie awards, made lists of "the 10 best movies of 1996," became a critical darling, and turned the Wachowskis into a hot property. Ever wondered why a major studio was willing to trust a $60 million blockbuster to a pair of nearly untested directors? It's because of those critics gushing over Bound.

Interestingly, the Wachowskis' forgotten first movie is now considered as groundbreaking as The Matrix. Its LGBT themes, lesbian heroes, frank depiction of gay sex, and ascribing of agency to its queer characters has led AV Club to call it a benchmark of gay cinema.

It was the first onscreen depiction of 'the Matrix'

It probably wouldn't surprise you to learn that The Matrix wasn't the first onscreen depiction of a virtual world. By 1999, the idea was pretty firmly established in sci-fi. You might be surprised to hear that it wasn't the first onscreen depiction of a virtual reality world called "the Matrix" that is powered by human batteries, where you can make impossible things happen, and in which getting killed causes your body to die in real life. That familiar sounding concept first appeared onscreen in 1976, and it came courtesy of long running sci-fi series Doctor Who (via AV Club).

The 1976 serial The Deadly Assassin starts out as far from Keanu Reeves swanning around in a trench coat as you can imagine. The Doctor, played by Tom Baker, is on his home planet of Gallifrey to investigate an assassination attempt by his nemesis The Master. So far, so not Matrix. Then, in Episode 3, the story suddenly gets a lot more Wachowski. The Doctor encounters a virtual world called the Matrix, which is built upon pretty much the exact same rules as the Wachowskis' Matrix. The only difference is that the "one" in this Matrix is evil and uses his reality-bending powers to summon evil clowns instead of getting his kung-fu on.

Although it's unlikely the Wachowskis ripped off Doctor Who, it's not the only time the BBC series has presaged major blockbusters. Alien and The Terminator are both foreshadowed in early episodes of Who.

The whole 'humans as batteries' thing represents a major plot hole

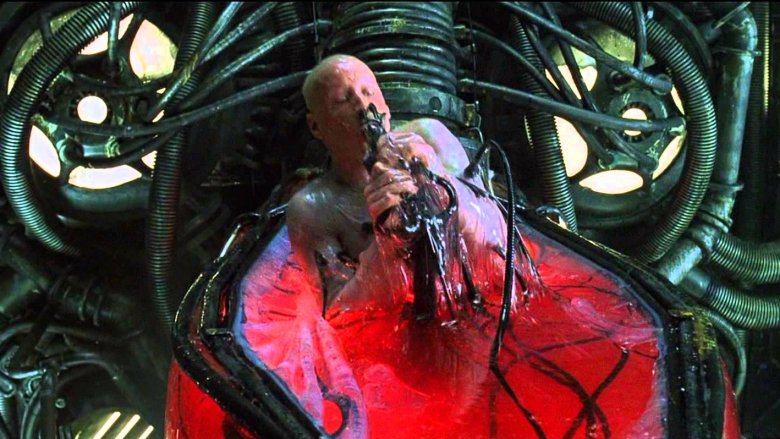

The Matrix ain't hard sci-fi. It's action blockbuster with sci-fi trappings, which may be why it's stuffed so full of contradictions and inconsistencies. (Why doesn't Cypher need to jack in to the Matrix? Why the heck is Agent Smith programmed to have a receding hairline?) But where plot holes are concerned, it probably does better than you think. The famous "humans as batteries" problem has been solved. Many times.

The issue goes something like this. Humans would be insanely inefficient as batteries. Generating a virtual world for them to live in would be even less efficient. Why don't the machines just use braindead humans or, better yet, braindead cows to generate their power. (Although even that would run foul of the first and second laws of thermodynamics, given what we learn about how humans are fed in the film.)

Remember Morpheus' comment about the machines having a "form of fusion"? As bloggers have pointed out, fusion would render the human battery system pointless, meaning the machines must keep humans alive for another reason. Some theorize it's because the machines have to obey Asimov's laws of robotics, even after the war (the not-killing-all-humans law). Others think the machines require humanity's imagination, as it's the one thing robots lack. Yet others think the machines were the good guys and put humanity in what's basically a virtual daycare center just to stop the neverending series of nuclear holocausts. Take your pick.

It only became a hit on home media

Everyone loves an underdog story. It's so much more satisfying to read about how someone overcame unlikely odds than to read about how the favorite won again. That's probably where the myth about The Matrix being a dark horse comes from. Again and again, people like to trot out the idea that the film wasn't a hit at the box office and only picked up a major following on DVD thanks to savvy fans. It's a nice story, but a story is all it is. Look at the box office numbers, and it's clear The Matrix hit the ground running and didn't stop until it had kung-fu-kicked the opposition into a screaming pulp.

Box Office Mojo has the exact numbers. The Matrix opened at #1 on its opening weekend. It made $171.4 million domestically, and $292 million worldwide. While those numbers don't sound all that impressive today (Batman v Superman made nearly $900 million globally and was still considered a disappointment), in 1999 it was enough for The Matrix to become the fourth-most profitable film worldwide. It outperformed the newest James Bond, The Mummy, the second Austin Powers, The Blair Witch Project, and the Pokemon movie. Those are the stats of a bona fide success — especially on a mid-range budget — not the stats of some underdog struggling to make a splash. It was backed up by an advertising campaign that saw the film profiled in major magazines like any other upcoming blockbuster.