The Navajo's Most Horrific Legend, Skinwalkers

Ask people to name a wilderness-dwelling monster from folklore and you're likely to hear some similar candidates. In the Americas, we've got Bigfoot, sometimes called by the indigenous Salish name Sasquatch, per Britannica. There's also the snowy version from the Nepalese Himalayas, the Yeti, aka The Abominable Snowman. We've also got the tried-and-true werewolf, and the bloodsucking Mesoamerican cryptid, El Chupacabra. Dig deeper and there's the tall, emaciated incarnation of famine and winter described by various Native American tribes, the Wendigo, per Legends of America. As Mental Floss outlines, there are countless such stories from around the globe, persisting from generation to generation and continuing to terrify and fascinate.

Skeptics can easily roll their eyes at even the mere mention of these names. Disbelievers can point to the lack of physical evidence or ample, non-blurry video footage, especially in an age of nigh-compulsive video recording. They can also point to the likely origins of all such legends as cautionary, "Be careful out there in the woods" tales to ensure that people stay clustered together within the safety of civilization.

Sometimes, though, enough stories pile up to make even the most hardened skeptic wonder what's going on. Such is the case with Navajo skinwalkers, creatures so terrifying, so malevolent, that tribespeople won't even speak their name for fear of drawing their attention. Skinwalkers are basically magicians twisted by darkness who take the form of loved ones to lure people to their death, as sites like History Daily describe.

Witches of pain and misfortune

Skinwalkers have gotten a fair amount of attention in recent years — at least in certain on- and offline circles — in large part thanks to the abundance of disturbing testimonies from eyewitnesses, both Navajo, and non-Navajo. Written accounts on sites like Live About and Reddit, as well as loads of narrations of encounters by YouTubers such as Lazy Masquerade (here, here, and here, to name a few), all tell versions of the same traditional tale. Taken all in all, a clear and consistent portrait emerges of what we might call a "typical" skinwalker experience. And to be sure, there's a specific modus operandi at work beyond, "scary thing lurks in woods at night."

That being said, encounters invariably happen at the same as many creepy things: at night. Encounters never happen in urban areas, but always in remote, forested regions. There's typically a family involved or a group of close people — there's the first key to what distinguishes skinwalker experiences. Often, one person in the group thinks they hear the voice of a loved one, even someone in the group, but the voice sounds hollow or staticky. They'll go to check, and see a bizarrely stiff version of the person they heard, almost like that person is wearing a skin or mask. Or there'll be an as-yet-transformed creature that looks like a werewolf. The creature wants its victim to follow, and in so doing, to die.

A tale of good vs. evil

So yes, skinwalkers are disturbing. It's the inclusion of loved ones into the tales that make them stand out. Who could resist following the voice of a friend, spouse, or parent? It makes skinwalkers come across as intelligent and observant hunters, not mindless beasts roving dark woods. But is the intended lesson as simple as, "Don't follow those on a dark path into darkness?" Where do skinwalker tales come from, exactly?

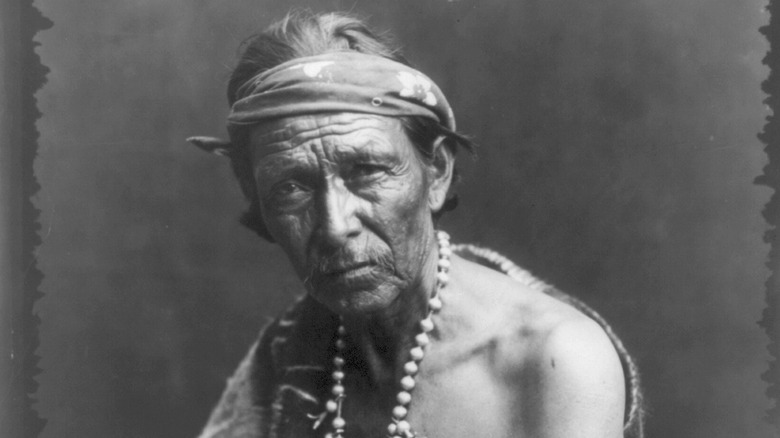

Ultimately, skinwalkers very clearly reflect the cultures that believe in them. We've discussed skinwalkers as originating with the Navajo. As New Mexico Explorer explains, they also appear in related tribes like the Hopi, Ute, and Apache in the overall Mesa Verde region of the Southwest U.S. at the intersection of New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and Utah. All such tribes are connected to each other, and part of the same, larger Pueblo Indian group of indigenous peoples that settled in the area at least 7,000 years ago, as Legends of America says.

Navajo culture, in particular, places a very heavy emphasis on good vs. evil in a cosmic sense. As New Mexico Explorer says, all actions must abide by universal harmony, or hozho. Navajo practices incorporate ritual magic meant to maintain universal balance and cleanse places and people, as Legends of America describes. Skinwalkers are those Faust-like magical practitioners who took things too far. In the struggle of good vs. evil they got twisted from healers into deceivers.

He goes on all fours

At the very least, skinwalkers are a warning against involvement in what we might call "black magic." Their stories steer people away from the "dark wind" that blows through life, as author Tony Hillerman puts it on New Mexico Explorer. They're "naaldlooshii" in Navajo, or "he goes on all fours" — less than human and more like a beast. They quite literally stalk the vulnerable and try to beckon people into the same darkness as them. They can even wield the love and care between people to do so, by taking on the form of family, friends, and so forth. As Sky History points out, skinwalkers sound very much like modern, pop culture Sith from "Star Wars" lured to the dark side of the force. And just like the Sith from "Star Wars," skinwalkers necessitate a master and a pupil.

Legends of America says that someone must be formally initiated into a "secret society" to become a skinwalker. Such a person does this out of his (skinwalkers are almost always depicted as male) own will. As Atlas Obscura says, "Skinwalkers want to be monsters." They're irredeemable creatures of absolute evil who must commit "specific atrocities such as murdering a family member" to complete their induction and gain their powers. Sky History also says that someone might incidentally become a skinwalker through "social transgressions" and "the breaking of tribal taboos," which is a very clear way to say that tribal practices are considered holy and inviolate.

The powers of beasts

Like we mentioned, traditional Navajo culture is deeply ritualistic. "Adishgash," one of many Navajo terms for witchcraft, is a part of everyday life, as New Mexico Explorer says. The 1995 book "Hand Trembling, Frenzy Witchcraft, and Moth Madness: A Study of Navajo Seizure Disorders" describes how, in traditional Navajo belief, medical conditions like seizures were attributed to "sibling incest, sexual witchcraft, or possession by a supernatural spirit," as publisher The University of Arizona Press describes. This is how embedded the Navajo believed magic was in their world.

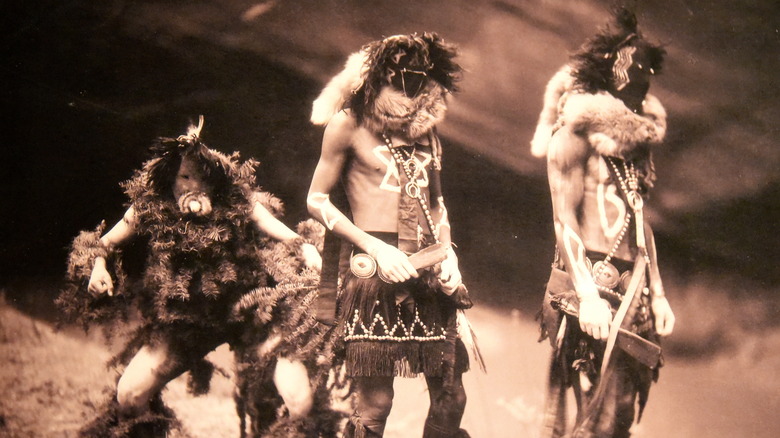

When a magical practitioner — or someone just seeking power — turns from helpful to harmful forces, the Navajo say that person has stepped on the "Witchery Way," per Legends of America. It's believed they use human corpses for their ingredients, down to the bones, and craft "concoctions that are used to curse, harm, or kill intended victims." They're telepathic and can cause disease, famine, drought, disaster, and more. They can shape-shift into whatever animal grants them whatever skill they need to roam, kill, and hurt: the strength of a bear, the speed of a coyote, the claws of a cougar, and so on. Their rituals are vile versions of otherwise typical feasting, dancing, sand art, and more, and involve acts like incest and necrophilia. Sometimes they wear animal skins, skulls, or antlers. That's why to this day, the Navajo "consider it taboo" to wear anything made from a predatory animal.

Enduring life lessons

Belief in skinwalkers is very much alive within present-day Navajo communities. On New Mexico Explorers, author Tony Hillerman writes, "A lot of Navajos will tell me emphatically, especially when they don't know me very well, that they don't believe in all that stuff. And then when you get to be a friend, they'll start telling you about the first time they ever saw one."

Commenters under YouTube videos about skinwalkers often state that they're Navajo, that they've seen skinwalkers, or that skinwalkers are taken very seriously. Such people who step forward are rarities though because it's considered bad luck to talk about skinwalkers, as Legends of America describes. At worst, it's considered an invitation.

No matter if skinwalkers are real or not, or if people believe in them as physical, actual beings, they teach the same lessons. They advise not straying from Navajo values or following in the footsteps of those who have. They warn against disrupting the balance of life or seeking power that isn't one's own. They remind people to not descend into uncaring, atavistic behavior better suited to wild beasts. And like many tales for the young, they advocate taking care regarding who one trusts, and remaining cautious of dangerous places and situations. That's all excellent advice. And even if skinwalker legends began as nothing more than shabbily-dressed loners wandering around villages, it's best to do as the Navajo do: steer clear of strange voices, dangerous places, and dark paths.