The Disturbing History Of The British Tabloids

For many Americans, the word "tabloid" is likely to conjure images of gossipy rags lining the check-out aisles of grocery stores. British columnist Peter Preston made a similar assessment in the pages of the Guardian. The collection of simply written, poorly sourced gossip and outright flights of fancy he found didn't impress him — nor did they bear much resemblance to the tabloids he was used to back home.

Technically, the term "tabloid" refers to the half-sized paper used by some newspaper editions (per Britannica). But where tabloids in the United States have become associated with scandalous titter largely divorced from hard news, Britain's have a very different character. Oh, they still go in for gossip and sensational claims, and they have a reputation for eschewing depth and nuance. But the British tabloids are daily newspapers that cover major events. And, far from being something to thumb through to kill time at the store, they are a powerful and influential component of the mainstream British media.

The significance of the tabloid press to Britain has been a cause for lamentation by many. The 2015 book "Tabloid Century: The Popular Press in Britain, 1896 to the Present," noted the widespread stereotype of the tabloids as repugnant gutter press (via a Reviews in History review). The same book argues against painting with such a broad brush. Nevertheless, British tabloids have been associated with some unsavory media episodes in recent decades.

The Harmsworths birthed the British tabloid

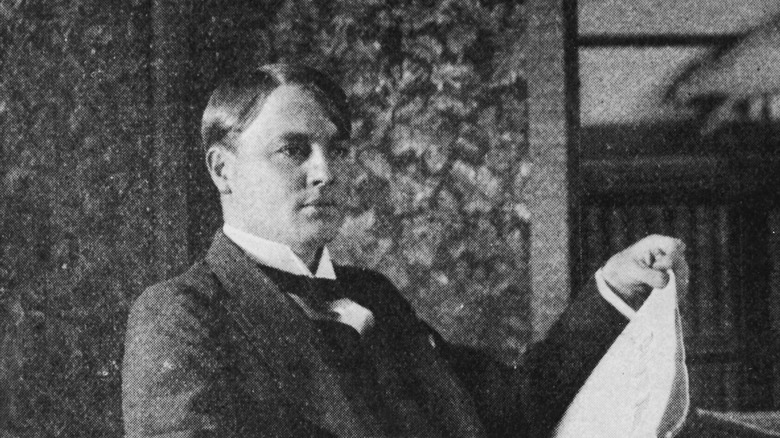

Per Britannica, the British tabloid as we know it grew out of an international partnership. When America's Joseph Pulitzer asked Britain's Alfred Harmsworth, a freelance reporter-turned-newspaper publisher, to be a guest editor for the New York World, Harmsworth turned out a tabloid-sized edition that crammed as much as possible into its pages. The brevity of the copy was something Harmsworth employed in Britain for his own publications, which emphasized photos, comics, and heavily sensational stories on eyeball-catching topics: crime, scandal, and sports. Thus was born the modern tabloid journalism.

Harmsworth, later styled the 1st Viscount Northcliffe, founded two of Britain's most enduring (and notorious) tabloids, the Daily Mail and the Daily Mirror. Per the Financial Times, he also took over two prominent broadsheets, The Times and The Observer, at least for a time. With his brother Harold minding the business side of things, Harmsworth exercised a strong editorial hand on the publications he owned, pushing for a style and content that would broadly appeal to readers of decent education, middle-class status, and imperialist values.

Harmsworth made the news himself at times; his attacks on the way the government conducted policy during World War I were so fervent that he got the job of supervising propaganda, to devastating effect for German forces (per the Daily Mail). And he supported and compensated his journalists well. But Harmsworth was also an anti-Semite whose political power was strong enough to help force a prime minister from office.

The Daily Mail once went to bat for the Nazis

Alfred Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Northcliffe, was Britain's most powerful press baron in the early 20th century, according to Andrew Roberts' biography "The Chief" (via a review by the Financial Times). He helped to oust Herbert Asquith from the premiership and shifted policy during World War I. While Roberts frames these political interventions positively, they weren't the only moves Harmsworth and his brother Harold made in British or international affairs.

According to The Times of Israel, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party came to power in 1933, the Harmsworths' Daily Mail was quick to profess support. This was at Harold's personal directive. He took up the pen and personally wrote a sympathetic article about Benito Mussolini's fascist takeover of Italy in the 1920s. He did the same for Hitler in 1930 and even briefly championed Britain's own fascist party four years later.

It's worth noting that many British newspapers were sympathetic or at least not hostile to fascism in the '20s and '30s. Given the choice between fascism and communism, many considered the former the lesser evil. The Harmsworths, both anti-Semites, went further than others in the press with his praise. But, as Roy Greenslade pointed out in The Guardian, the influence of such articles was limited, and coverage of the Nazis in the Mail shifted rapidly when Harold's son took over the publication.

British tabloids shaped opinion throughout the 20th century

In 2015, Adrian Bingham and Martin Conboy published "Tabloid Century: The Popular Press in Britain, 1896 to the Present." Despite the reputation of the tabloids as a cesspool of unethical reporting, "Tabloid Century" (via a Reviews in History review) took pains to challenge that stereotype. Without glossing over the flaws of British journalism, the book gave ample space to discussing more nuanced aspects of the tabloid press and their influence.

"Tabloid Century" divided the history of the British tabloids into three eras. The first, dating from the beginning of the 20th century to the 1930s, saw the development of tabloid journalism as a style, built on short, easily digestible copy. The dominant papers were largely supportive of the Conservative party in politics, and coverage of wars was often uncritical. Yet even in this era, the tabloids could take up causes that affected the middle class, and the changing role of women in the 1920s was given fair hearing.

Such trends became more pronounced in the second era of the tabloids, dated from the 1930s to the '70s, when openly left-wing papers emerged. Postwar reconstruction and shifting views on race and war were influenced by tabloid coverage. At the same time, sensationalism, sex, and scandal were pursued with greater fervor, leading into the modern era of tabloid journalism marked by Rupert Murdoch's acquisition of The Sun in 1969 and the spread of the tabloid style to other media.

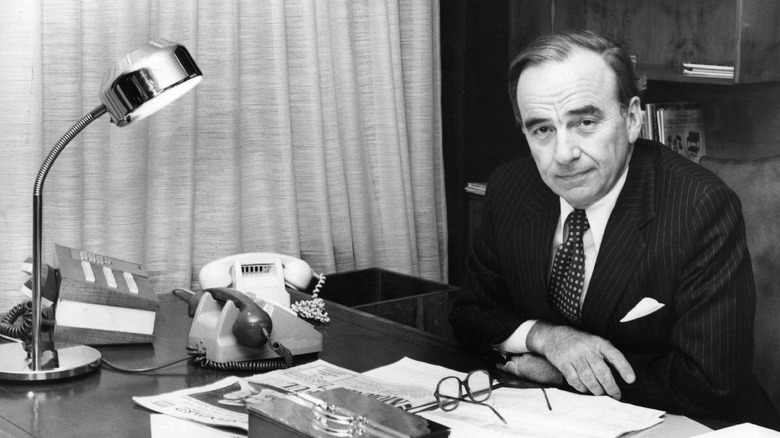

Rupert Murdoch changed everything

Britain's most powerful press baron of the early 20th century, Alfred Harmsworth, had an enthusiastic young protege named Keith Murdoch, who got a £5,000 investment from his old boss when he started to build an Australian newspaper conglomerate. That friendship, and that investment, link the most influential publisher of the prewar era with his modern equivalent: Rupert Murdoch, Keith's son (per the Financial Times).

Murdoch's acquisition of The Sun in 1969 was a pivotal moment in the modern history of British tabloids. He was highly engaged in the papers he owned; Reuters reported that, in the early days of his ownership, he personally decided which stories to run, and the pressure he puts on editors and reporters to catch eyes and make waves is said to be relentless to this day. The tabloid style was well established by the 1970s, but Murdoch's escalation of sex, celebrity, and conservative politics ran up the circulation numbers and saw a lurch by the industry as a whole in his direction (per the Daily Beast).

Murdoch's control over the U.K. press extended as he bought other tabloids and broadsheets, and despite his conservative leanings, his media empire has been flexible — and powerful — enough that politicians of all stripes seek to curry his favor (per NPR). The anything-for-a-story mentality he bred has contributed to the dark reputation of modern tabloids, and was the subject of a 2019 Broadway play, "Ink."

A competitive market helps drive their ruthlessness

On occasion, British journalists and press watchdogs have been asked to explain the unique culture of the country's tabloids. Writing for Polis, the media think tank of the London School of Economics, Charlie Beckett offered a mild pushback on the idea that Britain's tabloid culture was so singular; their style of coverage exists elsewhere in the world, often in different media. But he did concede that the packaging of titillation and hard news in powerful newspapers was a British phenomenon, one he and commenters solicited on social media linked to a combination of historical, cultural, and industrial factors. Plus, Beckett noted, the tabloids are a highly competitive field.

The intense competition for readers has been taken up by others as a reason for the venom in modern tabloids. Rupert Murdoch was reportedly obsessed with making The Sun more popular than the Mirror when he bought the former, an obsession strong enough to warrant Broadway dramatization (per the Daily Beast). Between the tabloids and the broadsheets, Britain has nine major national newspapers still in print editions — the most in the First World, according to Foreign Policy. TV and internet outlets offer still more competition, and this has helped motivate some tabloids to leave ethics behind as they chase after content.

They are much more partisan than American tabloids

It's no secret that America's Fox News has a hard right slant to its reporting and opinion programming. But Americans who visited Britain — even Americans as media-savvy as political consultant David Axelrod — have been shocked by the partisanship of the British tabloids and wider media (per The Guardian). Avowed sympathy for a particular stripe of political thought is common in the British press, and Axelrod's assessment in 2015 was that British political parties had deeper connections with their ideological comrades in newsrooms than exist even between Fox and the Republican party in America.

It isn't only foreign observers who've taken note of how nakedly the British press take sides. Analytic firm YouGov found in 2017 that Britons broadly agreed that they had a partisan press, and that the majority of major newspapers skewed to the right. The Oxford Royale Academy assessed the political leanings of 11 publications and considered four to lean right, four to lean left, and the other three to be centrist or malleable. Of the tabloids, the Daily Mail — one of the most widely read and influential papers in Britain — was considered right-wing, while The Sun was labeled "populist." The Daily Mirror was counted as the one major tabloid on the left.

They clash regularly with celebrities

One thing American and British tabloids have in common is an obsession with celebrities. Actors, rock stars, and fashion models all move papers, and with the advent of television and online journalism, a splashy piece on a famous name can bring in desperately needed sales and ad revenue for a paper.

Roy Greenslade of The Guardian wrote that the relationship between British tabloid reporters and celebrities was positive once upon a time. Editors and reporters on entertainment beats happily socialized with the subjects of their stories. Greenslade saw nothing wrong with such friendliness, while others in the press found it a step too far away from journalistic impartiality. But after a change in reporting styles led by The Sun in the 1970s, pieces on celebrities in the tabloids took on a much more scandalous — and often heavily distorted — character.

Relationships between entertainment journalists and celebrities have become more tense since then, with the rich and famous growing more guarded and the tabloids turning more intrusive in response. There's also been an uptick in litigation against the tabloids in Britain. Some celebrities, according to ABC News, even seek out lawsuits that can play out in British courts. The burden of proof for libel is much lower in the U.K. than it is in America, and court costs are much less.

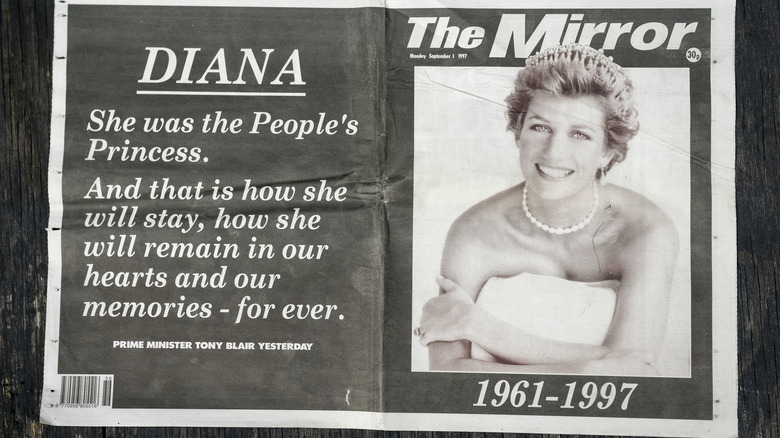

A tabloid was at the heart of the phone hacking scandal

The modern reputation of the British tabloids owes its unfavorable character in no small part to the phone hacking scandal. According to the BBC, journalists and editors at the News of the World, a 168-year-old News International publication, spent years colluding with private investigators to access and record voicemails on private cell phones to get scoops and angles. An intrusion into Prince William's privacy in the mid-2000s set off an investigation, and additional allegations of hacking — with extensive involvement by staff — mounted. When it was found that Milly Dowler, a kidnapping and murder victim, had been hacked by the News of the World, owner Rupert Murdoch chose to shutter the paper in 2011.

Closing shop didn't halt legal proceedings. In 2014, multiple figures connected with the News of the World were brought to trial on charges related to the hacking itself and efforts to suppress evidence. While some, including chief executive Rebekah Brooks, were acquitted, editor Andy Coulson was convicted, and five figures involved in the hacking, including private investigator Glenn Mulcaire, pleaded guilty before going to trial. Mulcaire was earning £100,000 per year for his work, and the meticulous notes he kept on the messages he hacked were a key piece of evidence.

Phone hacking: the sequel?

The closure of the News of the World in the wake of accusations of phone hacking still haunts the British tabloids, and it may not be over yet. Bloomberg (via The Washington Post) drew a direct comparison to the outcry against the News of the World a decade ago and the lawsuits that were launched against Associated Newspapers Ltd. in 2022. Associated Newspapers owns and publishes the Daily Mail, currently the most widely read of Britain's tabloids.

Those pursuing legal action against the Mail include Elton John, Sadie Frost, and Prince Harry (per The Guardian). Besides fresh allegations of phone hacking, there are also claims that the Mail had bugs planted in homes and cars, bribed police officers, and illegally obtained medical and financial records. For its part, Associated Newspapers has maintained its innocence and questioned the substance and the age of the allegations.

Just as the News of the World's downfall was associated with its hacking of murder victim Milly Dowler's phone, the Mail's current accusers include Lady Doreen Lawrence. Lawrence is the mother of Stephen Lawrence, victim of a notorious, racially motivated murder in 1993. The Mail championed Lawrence's case and pointed to its efforts for years as an example of the quality of its journalism, but Lady Lawrence suspects her family was improperly pursued by the paper before it decided to take up their cause. Guardian editor Jim Waterson suggested that her charges were the most sensitive to date for Associated Newspapers Ltd.

How powerful are British tabloids in political and royal affairs?

Among the claims made by Prince Harry and Meghan Markle in their 2021 interview with Oprah Winfrey was what Harry dubbed the "invisible contract" between the House of Windsor and the British tabloids. "It's a case of, if you as a family member are willing to wine, dine, and give full access to these reporters, then you will get better press," he told Winfrey (via CBS News). The inverse has been alleged to be true as well; former editor of The Sun Kelvin MacKenzie suggested that, if the public appetite called for negative stories about a member of the royal family, the tabloids would feed that perception.

But in a constitutional monarchy, royalty is responsible for ceremony, symbolism, and soft power. Politicians who don't court the tabloids — or, worse, dare to criticize their influence — have been subjected to brutal coverage and humiliating publicity stunts, according to The New York Times. The vehemence of tabloid coverage has helped shift elections and policy. After the phone hacking scandal of the News of the World came to light in 2011, some figures in government became more outspoken against the industry, but Guardian columnist Andy Beckett suggested in 2016 that Brexit demonstrated their political power remained unchecked: Many of the tabloids were in favor of leaving the European Union and drove coverage accordingly.

British tabloids have their defenders

It's not easy to defend the tabloids. The word itself has so many negative connotations, and episodes like the phone hacking scandal of 2011 do no favors. And yet some in the more respected corners of the British press are prepared to champion their more controversial cousins — or at least their potential to be more than they are.

Writing in The Guardian not long after the hacking scandal, Jonathan Freedland found the tabloids unreflective even after so damaging an incident. But Freedland cautioned against doing away with the tabloids altogether. He noted the Daily Mail's role in pursuing justice for Stephen Lawrence in the 1990s, the Daily Mirror's stance against the Iraq War, and even the disgraced News of the World's investigative reporting on sports scandals as examples of the tabloids' ability to function as a healthy organ of the press at times.

Other defenses of the tabloids are more concerned with freedom of the press than any one piece of it. Beth Daley of The Conversation, answering a high-profile campaign against the tabloids in 2014, acknowledged the harm done to public figures by the tabloids but rejected some of the criticisms levied. Daley found some of the critiques, founded in academic theory, clashed with the working realities of journalists, and she felt that suggested remedies to the tabloids' flaws that involved new laws or judicial action could restrict free inquiry.

Will the industry reform?

If Britain's tabloids exercise unhealthy influence on the media and political climates of the country, intimidate ministers and monarchs alike, and take part in illegal or unethical practices to get stories, the question becomes — can they reform as an industry, and if so, will they ever? Lord Justice Brian Leveson attempted to provide an answer with a report in the wake of the phone hacking scandal in 2012. Per The Guardian, he urged the establishment of a new press watchdog organization, independent of the government or paper owners, with accompanying legislation to ensure freedom of the press was maintained.

According to Foreign Policy, Parliament was prepared to support such a watchdog, but no legislation to create or empower it ever made it out of Westminster. Instead, major media companies formed the Independent Press Standards Organization (IPSO) to act as a self-regulatory body. Its efforts in that capacity have not been viewed favorably, and it's unlikely to be a coincidence that the companies that created IPSO lobbied heavily against the government taking up Leveson's recommendations.