Mount Everest's Strangest Artifacts And Objects

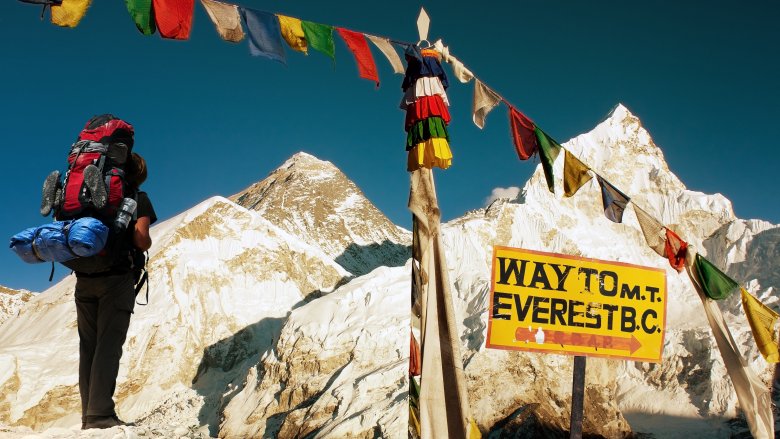

Mount Everest is the world's highest mountain at just over 29,000 feet above sea level — if not quite the tallest, if you want to be a pedantic jerk about it— with a history that's inspiring, sobering and baffling in equal measure. Hundreds of thrill-seekers, tourists, and seasoned pros try to summit this sucker every year, and they don't usually come back with everything they left with — if they come back at all.

As the air gets thinner and the heavens loom ever closer, things can start to get strange, and the various things you might spot and stumble upon along the way can be even stranger. Amidst the vast expanses of snow and rock and ice, and across countless expeditions led by the kinds of colorful kooks crazy enough to, well, lead an Everest expedition, this great peak's treacherous slopes have definitely hosted their fair share of oddities over the years. Here are just a few of them.

Rainbow Valley, a multicolored open graveyard in the clouds

Everest has racked up a hefty body count over the last century — well over 200, according to the BBC, and most of those bodies are actually still there. After about 26,000 feet, you enter what's known as the "Death Zone," the final stretch below the summit where the oxygen levels become too low to support human life, where body and mind start to fail, and where the mountain claims most of its victims, making the "Death Zone" name entirely appropriate. The name "Rainbow Valley", on the other hand, tends to conjure up happy images of childhood theme parks and Super Mario levels, when really it's just a vast trail of frozen death.

So why "Rainbow Valley"? Well, it's because of the brightly colored down jackets and climbing equipment still attached to the cadavers that litter its surface. Rainbow Valley is a haunting stretch on the northern side of the mountain, residing comfortably in the Death Zone. When climbers perish here, they're frozen in place, and after a certain point removing their colorful corpses becomes too difficult, too expensive, and too dangerous — so they remain as macabre landmarks.

In 2014, though, adventurer Noel Hanna (via BBC) claimed that only a couple of bodies were still visible in the area where typically there'd be as many as ten, having obviously been moved somehow or covered over. But the Death Zone isn't getting any less deadly, and, with so many people still attempting the climb every year, it seems like Rainbow Valley will continue to be this ever-present reminder of their fragile mortality, a grim sign that the end approaches, one way or another.

A mountain's worth of human feces

You're climbing Everest, and you're about half a day's journey from the next camp. You're surrounded by nothing but snow, rocks, ice pits, and maybe a couple of other climbers in the same situation. You already know you shouldn't hold in number one, so you find a nearby tree and take care of business. But if and when you need to vacate your bowels, it's not like you can just slip into the nearest McDonald's bathroom and be on your way, so you dig a hole in the snow and you do what you gotta do. But all of this errant pooing has added up, and the mountaineering community now has a real mess on their hands in more ways than one.

Up to 26,500 pounds of human excrement is left behind on the mountain each season, according to the Washington Post. When anyone uses base camp's toilet facilities, their, uh, deposits can be properly disposed of. But above base camp is a different story. The waste has been piling up, and what comes up must come down. The water sources below have been badly polluted as a result, and the spread of disease has become a significant risk.

Call it an epoodemic, call it a pootastrophe. Or take the above-linked Washington Post journalist's lead and call it a "fecal time bomb," if you're feeling fancy. But it's actually a pretty serious issue. Even the president of the Nepal Mountaineering Association stepped in to warn that the level of human waste on the mountain had actually become critical in 2015. Let's just hope that bomb isn't in any rush to go off.

Tons and tons of garbage

No one knows exactly how much garbage is on Mount Everest. But with around 16 tons having been removed so far, according to the BBC, and much more remaining, scientifically speaking it's safe to say that it's a few metric buttloads. This includes discarded tents, broken equipment, eating utensils, cans, wrappers, empty oxygen bottles — you name it. Nothing you wouldn't find strewn about the place after a couple of days at Burning Man, but at the top of the world it's a lot harder to make sure everything gets cleaned up eventually.

It's not all that surprising when you think about it. With around 300 hopeful mountaineers and as many accompanying Sherpa guides attempting the climb every year, and over 4,000 climbers in total having scaled it so far, Everest's slopes were never going to remain pristine. But the sheer volume of garbage to be found there is still shocking. At this rate, Everest is well on its way to becoming the world's biggest trash heap.

All is not lost though, and efforts are being made to give the old girl a proper tidying. In 2012, artists from Nepal tried to raise awareness for the clean-up effort by sculpting 1.5 metric tons of garbage found on the mountain into works of art. And as of 2014, climbers have been required to return to base camp with 18 pounds of rubbish or risk losing a $4,000 deposit.

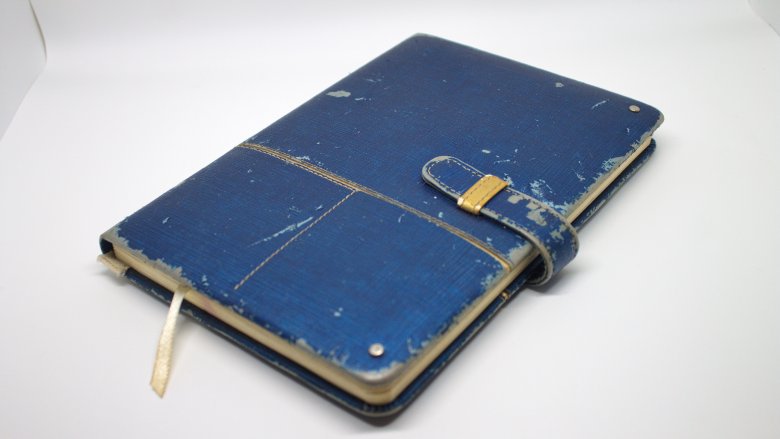

One colorful climber's fascinating diary

Over in England circa 1934, a very peculiar man had a very peculiar plan. The man was Maurice Wilson, a God-fearing Yorkshire lad chock full of self-belief and unrealistic expectations, and the plan was to ascend Mount Everest with little climbing experience, rubbish equipment, and a whole lot of faith. He was quite a character, and we know everything we know about his attempt and his various eccentricities because his diary was found along with his body a year later.

Wilson had wanted to ascend most of the way in a second-hand bi-plane, despite not knowing how to fly. This didn't work out, even if he did manage to fly all the way to India, and he set off up the mountain on foot instead. Incredibly, on his second attempt, he passed 21,000 feet before his Sherpa companions refused to continue and begged him to turn back. He pushed on alone, and his body was found wrapped in a tent a little higher up. An optimist right up to the bitter end, his final diary entry was "Off again. Gorgeous day".

In 1960, the plot thickened when a Chinese expedition came across both a tent and a woman's shoe at 21,000 feet. Together with the women's garments supposedly found in Wilson's rucksack and the fact that, according to the diary, he worked in a women's clothing store, these items were posited to have belonged to the ill-fated climber. So he might not have reached the summit, but he gave it a hell of a go — and probably looked fabulous the whole time.

Your friendly neighborhood Himalayan jumping spider

Cute, right? No? Well hang on, don't throw your computer/phone/device of choice into the nearest incinerator just yet, arachnophobic friends — this extreme close-up is likely as close as you'll ever have to come to one of these guys in real life. That is, unless you plan to pass 20,000 feet on Everest.

According to ThoughtCo., these fuzzy little freaks measure less than half an inch end to end, they scurry and hop around the place, as the name suggests, and they've been found at 22,000 feet. You're not exactly spoiled for choice when it comes to food at this height, so the spiders make do with stray insects that are carried up the mountain by the wind. Other than maybe the bar-headed geese that have supposedly been spotted flying overhead during migration, there aren't really any other creatures found at this height, let alone calling it their home, making these spiders the highest known permanent residents on Earth.

The body of an Everest legend

Everest and mysteries go together like coffee and donuts. Questions of who did this, who saw that, and when, and how, and with whom, and why should they be believed, all abound when discussing Everest's tallest tales. The mountain is a breeding ground for this kind of speculation, and the question of whether or not Andrew Irvine and George Mallory were the first to reach the summit has endured as one of its greatest mysteries.

Some believe that Mallory and Irvine were the first to conquer Everest in 1924, 29 years before Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay's famous 1953 expedition. And there's little doubt that Irvine and Mallory at least came very close. In a letter to his wife written six weeks prior to the climb (via the New York Times), Mallory was convinced that it was going to happen, writing "It is almost unthinkable...that I shan't get to the top; I can't see myself coming down defeated." It's entirely possible that they did indeed reach the summit before dying during their descent.

Irvine's body remains missing, but Mallory's was discovered at almost 28,000 feet in 1999, 75 years after their attempt. The discovery of his body, eerily well-preserved and naturally mummified, reignited people's interest in the mystery — but fell just short of solving it. The final piece of the puzzle is thought to be Mallory's camera, which he almost certainly had with him. It still hasn't been found, though it's highly sought after for the secrets it might hold.

Marine fossils a long way from home

Geologically speaking, Mount Everest and the rest of its Himalayan neighbors are still relatively young whippersnappers at a sprightly 65 million years of age. As outlined by ThoughtCo., they began forming when Eurasian plate and the Indo-Australian plate collided, and the boundary between the plates has been steadily folding and pushing to reach its current height of 29,000 feet. A key piece of evidence advancing the notion of plate tectonics in the early 20th century, the above-linked ThoughtCo. article explains that 400-million-year-old ocean marine fossils can actually be found in the layers of limestone at the top of the mountain.

These fossils were deposited at the bottom of shallow tropical seas back in the day before eventually finding themselves on top of the world, weirdly but epically demonstrating how the sea bed has been forced up to the highest peaks of the Earth over millions of years through the collision of crustal plates. Aside from the usual awe and wonder that Everest inspires with its sheer scale and the tales of triumph and tragedy on its slopes, it's humbling to know that when we look at it, we're really looking at a monument to the dynamic nature of the Earth itself.

Green Boots, Everest's most morbid landmark

Of the numerous corpses lying in plain sight on Everest's slopes, some achieve a greater level of morbid infamy than others. The most well-known among these is probably the poor soul known as "Green Boots." So named for the bright neon green climbing boots still attached to its feet, Green Boots has become kind of a grim landmark for those attempting the climb from the north face. Almost every climber passes the Green Boots on the way to the summit, and most stop to take a rest at the adjacent cave.

The man is believed to have been Tsewang Paljor, an Indian climber who perished in an infamous blizzard in 1996, and his family are understandably none too pleased with the Green Boots moniker nor the macabre spectacle that has been made of his remains. Some solace came in May 2014 though, when Paljor's corpse was actually reported to be missing, despite the presumed difficulty of moving it at that height.

G-g-g-ghosts?

As if the deadly conditions and the open graveyard of frozen corpses weren't frightening enough, a trek up Everest could also land you an encounter with a ghost or two.

Just ask Italian mountaineer Reinhold Messner, possibly the single most accomplished climber to ever grace Everest's hallowed slopes. Among a host of other mountaineering achievements, he was the first to ever complete a solo summit of Everest, and he was the first to complete the climb without bottled oxygen — to say nothing of that magnificent head of hair. And during a 1980 climb, according to The Guardian, Messner said he felt the presence of a phantom ally accompanying him and helping him on his way.

Messner might be the coolest people to have had an experience like this on Everest, but he's far from the only one. British climbers Dougal Haston and Doug Scott, for example, claimed to have been offered ghostly help and comfort during a 1975 expedition, and Pemba Dorji Sherpa claimed to have encountered "spirits in the form of black shadows" in 2004. Pemba and others believe that these may be the restless spirits of those who have died on the mountain, doomed to wander aimlessly in lieu of a proper burial.

Considering the harsh conditions and the high altitude, skeptics have been able to write off most of these encounters fairly easily as hallucinations. But not everyone's convinced, and Everest will probably always be a veritable embarrassment of spectral riches for those looking to satisfy paranormal curiosities.

An abominable footprint

The yeti has been firmly rooted in Himalayan legend for a long time. Mostly confined to superstitious whisperings and folkloric tall tales at first, the notion of the yeti (lesser known as "snow-bigfoot") started earning more serious treatment after 1951, as CNN tells it. That's when mountaineer Eric Shipton came across a large, oddly-shaped footprint he believed belonged to that most abominable of snowmen. The photographs he took were printed in newspapers around the world, and yeti-fever started to spread like a snowstorm. The U.S. State Department even laid down some rules to be followed in the event of a yeti encounter in 1959.

Since then, other tantalizing discoveries have included thick tufts of black hair supposedly found at 19,000 feet on Mount Everest by Edmund Hillary, and there was even a scalp found in a Nepalese woman's home in 1960, thought to have once belonged to a yeti (mistakenly, as it turns out), and now housed in a nearby monastery.

Pesky science hasn't gone and disproved the yeti's existence outright just yet, though it has come close. In 2017, a study of nine DNA samples thought to be from yetis or yeti-like animals found that they mostly belonged to bears from the region. The legend lives on, though. And let's be real: if you were just a simple yeti trying to make your way in the world, and that world obsessed over every morsel you left behind and still insisted on calling you abominable, you'd probably want to stay hidden too.