The Messed Up Truth About Being A Performer At Woodstock

The Woodstock Music Festival, held in August 1969, was one of the most iconic events of the '60s. Originally advertised as "3 Days of Peace and Music," the Woodstock festival has far outlived anything its founders could have imagined five decades later. Its story has been told so many times that it's now practically public domain.

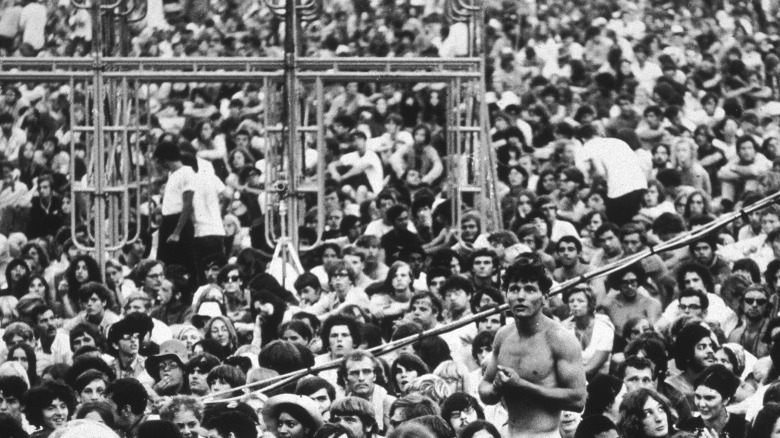

As History explains, coming off the heels of the successful Miami Music Festival the year prior, Michael Lang, John Roberts, Joel Rosenman, and Artie Kornfeld together came up with the Woodstock Music Festival to be held in Woodstock in upstate New York. Though only 50,000 fans were supposed to show up, soon nearly half-a-million hippies were clogging the arteries of the New York highway system, causing one of the most memorable traffic jams of all time. What followed was three-and-a-half days of music, unity, and quite a bit of chaos.

Even the performers at Woodstock were not insulated from the debauchery. From scheduling problems to cash flow issues and a lack of transportation, it was a miracle the festival even went on at all. But luckily, it did, and the stage was graced by some of the biggest legends in rock 'n' roll history, like Jimi Hendrix, The Who, and Carlos Santana. This is the messed up truth about being a performer at Woodstock.

Performers didn't know where Woodstock would be held until the last minute

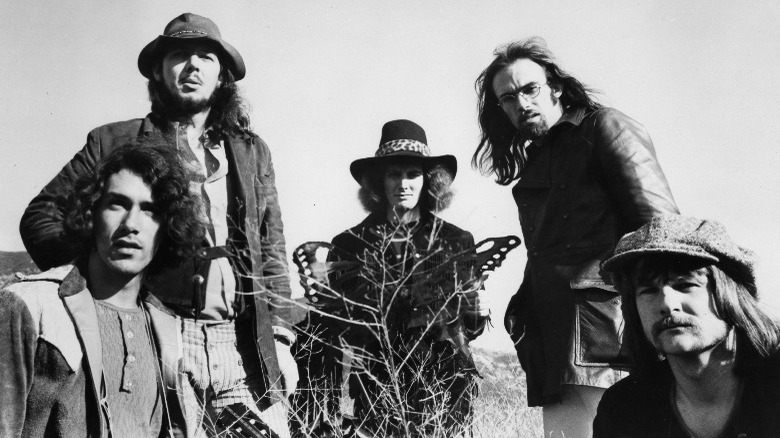

Even before Woodstock started, chaos abounded the organizers and potential performers. According to festival organizer Michael Lang in "Woodstock: The Oral History," he and his associates (pictured above) were set on holding a festival in upstate New York in the town of Woodstock. Yet, they still needed to find someone with a place there to actually host the festival, which proved to be easier said than done.

Immediately, there was opposition among the large landowners in Woodstock about letting their land be used for a festival. Lang's associates once found a site they deemed suitable, but he shut them down after surveying the area and not liking the vibes. Bands like Creedence Clearwater Revival, Canned Heat, and Jefferson Airplane had signed contracts with the festival organizers by the end of April (via Kevin Hillstrom's "Defining Moments: Woodstock"). Yet, they had no idea where the actual music festival was going to be held.

Lang and the rest of the organizers finally secured the now-famous site on Max Yasgur's dairy farm less than a month before the festival was set to start. This gave the performers and their management very little time to set up arrangements for things like accommodations and flights. Some performers like Tommy James even backed out when they heard the festival was going to be hosted at Yasgur's "pig" farm, a choice they soon regretted (via Kyle Meredith).

It was an adventure just to make it there

For many of the performers at Woodstock, the chaos of the event started right from the beginning. As Kevin Hillstrom explains in "Defining Moments: Woodstock," the massive traffic jams that snarled the highways getting to the Woodstock site were also a huge hindrance for the performers. The festival was scheduled to kick off on Friday, but starting on Thursday, hundreds of thousands of concertgoers started arriving in and around Woodstock. Barely any of the musicians were actually able to get to the site grounds before the festival started.

Locked in at hotels and motels with the highways basically shut down, the majority of the scheduled performers had virtually no way to get to Woodstock. With time running out as the festival crowds started to pile up, one can only imagine the perfuse sweat that organizer Michael Lang must have worked up worrying that the bands would not be able to arrive and perform.

However, in the end, the Woodstock organizers were able to save the day. Realizing that trying to drive on the highways was impossible, the organizers arranged for helicopters to fly the musicians from their lodgings directly to the festival. Though there were still massive scheduling issues, at least the bands had a way to arrive — even if some were very late.

Scheduling Woodstock performers was rough

The massive traffic jams that prevented performers from making it to Woodstock on time made a complete mockery of the originally planned scheduling. The scheduled opening act and their equipment were delayed and didn't arrive on time, so a new act had to be put in their place, which led to a late start (per Kevin Hillstrom's "Defining Moments: Woodstock").

To make matters worse, the weather added to the difficulties the traffic presented. Rainstorms saturated the area over the weekend, causing abbreviated and delayed performances. Some bands backed out of playing altogether due to the bad weather, causing last-second replacements to be slotted in where needed. On the second day of the festival, the lack of bands onsite forced the organizers to add even more people to the lineup, and they also had some of the Sunday performers play on Saturday, too.

The biggest tragedy of the bad scheduling, however, happened to Jimi Hendrix's "Gypsy Sun and Rainbows." Even though the festival was supposed to conclude on Sunday night, scheduling delays pushed things so far back that Hendrix did not come on stage until 9:00 a.m. the following morning. As a result, many of the attendees were too tired to stay for his set or thought the festival had ended the night prior (per John McDermott's "Hendrix: Setting the Record Straight"). Of the nearly 450,000 Woodstock attendees, just over 20,000 saw Hendrix perform due to poor scheduling.

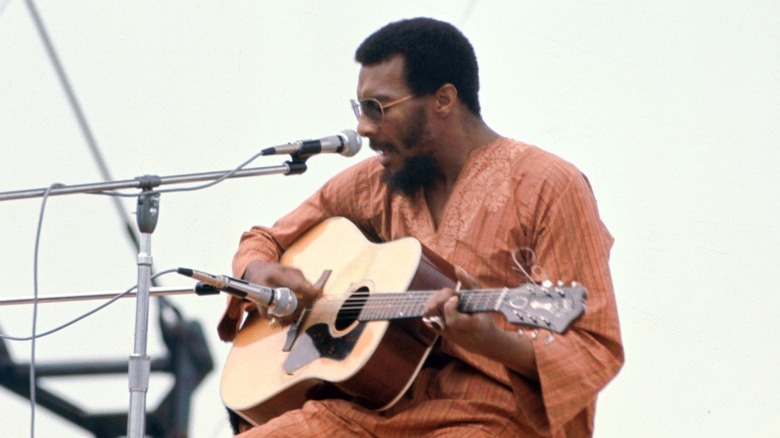

Richie Havens saved the day

One of the most memorable acts to perform at Woodstock was Richie Havens. Havens, a black folksinger, opened the Woodstock festivities with one of the best sets of the entire weekend, punctuated by his incredible performance of the song "Freedom." However, Havens actually wasn't supposed to open Woodstock at all. Originally, Michael Lang had scheduled the band Sweetwater as the festival's opening act (via Kevin Hillstrom's "Defining Moments: Woodstock"). But when they were not able to arrive on time, Lang instead turned to Havens to get things started.

As Havens recalls himself in "Woodstock: The Oral History," he was initially terrified of the idea of being the opening act. He was reluctant to face such a large crowd, and his bass player was still stuck in traffic on his way there. Luckily, his bassist arrived just in time and Havens ended up playing the most famous set of his career.

In order to fill up time, Havens played his entire catalog (and then some) and came out for numerous encores. One of the organizers kept pushing Havens out for more encores because they had no one else to follow up. Out of ideas, he came up with the largely improvised song "Freedom" while on stage, which was a total stroke of musical genius. Havens saved the day with his early and extended performance, getting Woodstock off on a solid musical footing.

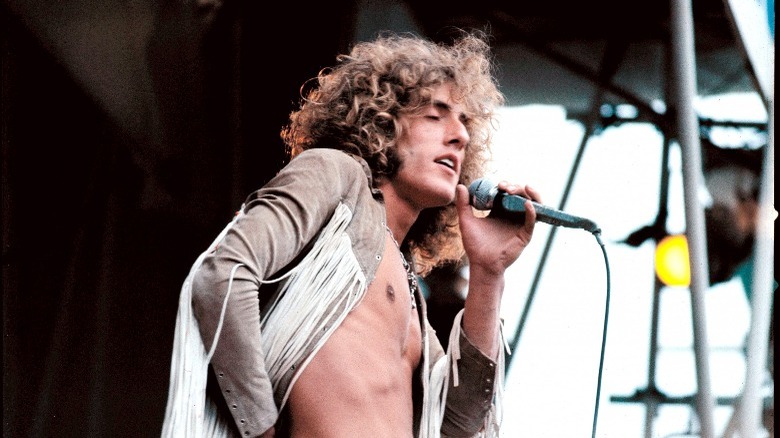

Several Woodstock performers were under the influence

It's no secret there was ample use of substances at Woodstock, considering it was at the height of the hippie era in the 1960s. Yet, most people don't realize just how much excess was involved on the performers' side. As The Who frontman Roger Daltrey wrote in his autobiography "Thanks a Lot Mr. Kibblewhite," pretty much every drink in the backstage area was laced with LSD — even the ice cubes. Daltrey accidentally ingested some when he drank a cup of tea, and he was still flying when he went onstage at 5:30 a.m. that morning.

Grateful Dead bass player Phil Lesh also recalled (via his autobiography "Searching for the Sound: My Life with the Grateful Dead") taking LSD at Woodstock, which he claimed was actually made in Czechoslovakia or the modern-day Czech Republic. He was also still under the influence when the Dead went to play, and their performance was marred by miscues and technical difficulties.

Carlos Santana was given mescaline by Dead guitarist Jerry Garcia on Saturday afternoon, thinking he had several hours before he was going to be onstage (via his autobiography "Universal Tone: Bringing My Story to Light"). However, immediately after taking it, he was forced to perform due to the various scheduling changes. On stage, Santana's guitar turned into an "electric snake," which Santana had to coax to stay straight. Still, his performance was incredibly memorable and helped put Santana on the map.

The weather made things dangerous

While Woodstock was certainly memorable for the incredible music and vibes over that August weekend in 1969, it was also notorious for something else: the weather. Even beginning on Friday night there were issues with rain storms that caused set delays and cancellations (via Kevin Hillstrom in "Defining Moments: Woodstock"). According to organizer John Morris (via Joel Makower's "Woodstock: The Oral History"), things didn't get any better on Saturday, and there were even gale force winds that afternoon.

The stage itself started to move with the wind, and the massive speaker towers started swaying, too. Soon lightning kicked in, and the stage had to be briefly cleared of all electronic equipment. During the Grateful Dead's infamous Woodstock performance that night, the performers kept getting electric shocks from their microphones and instruments (per Dead bassist Phil Lesh's "Searching for the Sound"). The wind also picked up again and people backstage began shouting about the stage collapsing in on itself.

Much of the Dead's electrical problems stemmed from the lack of adequate ground and the fact that the band was playing

"high-impedance instruments," as Lesh noted. Coming very close to a horrifying mass electrocution, the band was close to getting lethally shocked just by plugging in. Luckily, nothing happened and the Dead got through their set, though it was relatively poor by their own estimation.

Women performers were underrepresented at Woodstock

Looking back at Woodstock 50 years later, it's safe to say that it was a very male-dominated event. Of more than 30 acts to perform, fewer than a third included women members (via the Bethel Woods Center). However, even though they were underrepresented, the women of Woodstock put on some of the most memorable performances of the entire weekend.

Joan Baez performed one of the most legendary sets at the festival to close out Friday night, full of civil rights-themed protest music like "We Shall Overcome," which enthralled the audience (via Kevin Hillstrom in "Defining Moments: Woodstock"). Another highlight of Friday was singer-songwriter Melanie Safka. Safka was filling in for The Incredible String Band, who wouldn't go on during the thunderstorm, and immediately became a sensation. The performance jump-started her career, even though she performed for just under 20 minutes.

Legendary vocalist Janis Joplin also performed with her band Big Brother and the Holding Company. Though she was intimidated and heavily intoxicated, Joplin still performed a very well-received set. Her soulful and passionate vocals alternatively rocked and soothed the massive audience, forever linking her with Woodstock. Not to be outdone, Cynthia Robinson and Rosie Stone followed Joplin as part of Sly Stone's Family Stone Band, wowing the audience with their funky renditions. Though they weren't in the majority, the women of Woodstock certainly rocked just as hard, if not harder, than the men.

The crowd size was intimidating

For most of the performers at Woodstock, the nearly half-a-million large crowd was the biggest of their professional careers. Though many of them had become savvy veterans of the rock 'n' roll touring industry by that point, even Woodstock presented new challenges due to the incredible crowd size.

The opener of the show, Richie Havens, was nervous about being the first person on stage (via Joel Makower's "Woodstock: The Oral History"). He practically begged the organizers to put someone else up, as he had seen the crowd below when he flew in on a helicopter, and he sensed they were becoming unruly.

The Grateful Dead's performance was marred by technical issues and miscues, and according to Dennis McNally's "A Long Strange Trip," the band felt like they were under an enormous amount of pressure due to the crowd size. They also knew that Woodstock had spread beyond the confines of the close-knit hippie community, and was being written about and talked about by practically everyone in the country. Many formerly small-time bands felt very out of their element at Woodstock, but most of them managed to put their nerves aside and perform well.

Cash was king for Woodstock performers

While today we look back on Woodstock as one of the most monumental music events of the '60s, at the time its impact was much less certain. According to Kevin Hillstrom's "Defining Moments: Woodstock," the Woodstock organizers offered bands twice the normal rate to get them to agree to come. Two of the biggest paydays belonged to The Who and Jimi Hendrix, who were able to cash in big on their performances.

At some point, word got around that the organizers were low on cash flow, and two of the biggest bands, the Grateful Dead and The Who, both refused to go on stage without cash in hand, according to organizer Joel Rosenman's "Young Men With Unlimited Capital." Both of them demanded their remaining fee of $7,500 before stepping on stage, and Rosenman was worried that if word spread, soon everyone would be demanding cash right away — something they didn't have.

In the end, as Rosenman notes, he had to fly in the branch manager of the local bank by helicopter to get funds at the last minute. Or did he? According to The Who band member Roger Daltrey's autobiography "Thanks a Lot Mr. Kibblewhite," Rosenman made up the entire story about the helicopter adventure and simply wrote them a check. Either way, it's lucky they came to an agreement, or else Woodstock might have ended then and there.

Not everyone scheduled to perform at Woodstock came through

For all of the chaos and confusion of the day, it's a miracle that Woodstock was able to function as well as it did. The organizers had their hands full from the very beginning, as they quickly became responsible for the health and well-being of close to half a million hungry, thirsty, and mostly intoxicated hippies. While the festival went on for the most part without major issues, not every performer had the same experience, and some of them didn't even make it to Woodstock at all.

The massive traffic jams prevented several acts from arriving at the farm, including Iron Butterfly. According to Pete Fornatale's "Back to the Garden: The Story of Woodstock," Iron Butterfly was scheduled to perform at the festival and actually made it to LaGuardia Airport in New York City. The band sent festival organizer John Morris a telegram demanding to be picked up, to which Morris responded with a carefully crafted acronym of an expletive. Needless to say, Butterfly never arrived in Bethel.

Other groups were supposed to play at Woodstock but disintegrated before the festival could be held. The most famous was the Jeff Beck Group, which Beck purposefully broke up before Woodstock started, leaving them unable to play (per Annette Carson's "Jeff Beck: Crazy Fingers").

Performers were reluctant to be filmed

Sensing that the Woodstock festival would be important enough to document, the organizers of the festival hired filmmakers Mike Wadleigh and Bob Meurice to videotape the event (per "Young Men With Unlimited Capital"). According to Wadleigh, filming the performers was easier said than done. For one, they had signed the contract with the Woodstock organizers close to the start of the festival, leaving them shorthanded in terms of both crew and film (via Rolling Stone).

Because of their lack of film, Wadleigh and Meurice wanted to prioritize filming certain songs from each performer. Yet, even when they tried to work out a potential set list with some of the bands, it all fell to the wayside as soon as they got on stage. Another issue was the filming of the musicians, as some of them were very reluctant. Pete Townsend of The Who physically cleared the stage of Wadleigh early in their set, and it was only through luck that their iconic performance of "See Me, Feel Me" was captured.

Both The Band and Janis Joplin reportedly demanded exorbitant amounts of cash to appear in the film, sensing they had the upper hand. But in the end, it caused them to be cut from the movie altogether. Most performers ended up signing a release to appear, and the Woodstock movie ended up taking home an Academy Award upon its release.

Woodstock performers didn't always play nice

Woodstock was billed by the promoters as "3 Days of Peace and Music," and while that worked out for the most part, there were still some tensions. The audience at Woodstock was a confluence of anti-war protestors, civil rights activists, and young men and women looking to experience the music and unity of the era. They did not all see eye to eye (per History).

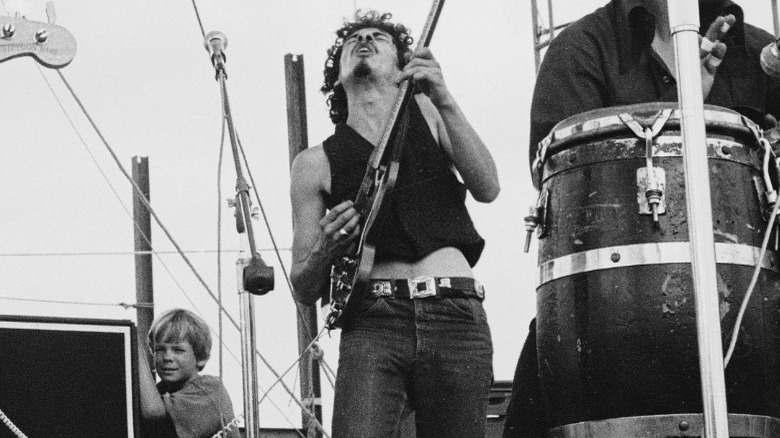

Though their set was known for their incredible performance of their rock opera "Tommy," The Who's set is also infamous for a few other reasons. According to organizer Michael Lang in "The Road to Woodstock: From the Man Behind the Legendary Festival," at the beginning of the set, guitarist Pete Townsend kicked filmmaker Mike Wadleigh to get him off the stage. But things didn't end there.

Halfway through their performance, prominent anti-war activist Abbie Hoffman got on stage and started talking about the Vietnam War and the recent arrest of John Sinclair for marijuana possession. While Townsend did not necessarily disagree with Hoffman's rhetoric, he had already warned everyone to clear the stage following the Wadleigh kick. When Hoffman came up and started his diatribe, Townsend smacked him with his Gibson guitar, sending him flying off the stage. It wasn't exactly the peaceful message the organizers had in mind, but it did clear the stage and allow The Who to continue to lay waste to the 400,000-odd fans in attendance.