Who Was Ora Washington, The First Black Woman Tennis Superstar?

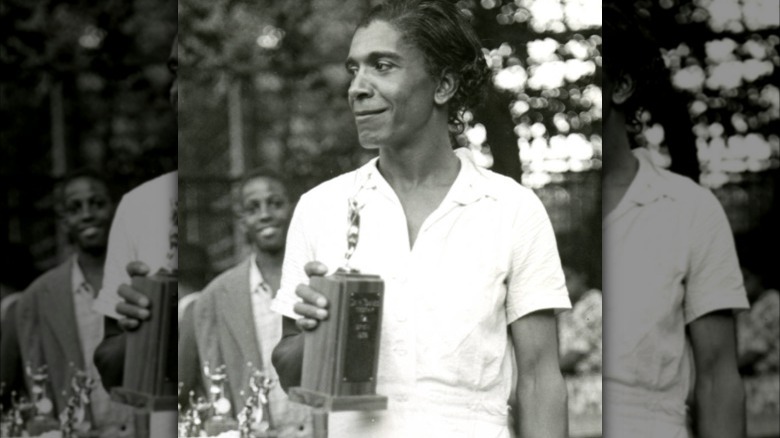

Ora Washington became an African-American tennis titan in the '20s and '30s when the U.S. was still segregated, long before the civil rights movement began (via The Washington Post). Despite winning stacks of trophies in both doubles and singles tournaments run by the all-Black American Tennis Association, she was not really celebrated for her talents until after her death. The entire time she was knocking out tennis records, she lived a fairly humble life working as a maid, a job she kept even after she left the sport (via WBUR).

In her time, Washington could only face other Black players, which meant playing in competitions that rarely got prestigious press attention. Only when the Black Athletes Hall of Fame was first created was Washington finally honored at a special event in 1976; the oblivious committee was unaware that she had already died (via the BBC). Her chair remained empty, and her name passed once more into obscurity. Today, she is increasingly recognized as one of the greatest athletes of all time.

Personal life and early years

The details of Ora Washington's early life are hard to trace, but we do know some things about her. She was born in 1898 or 1899 (per BBC) in Virginia to farm-owning parents but later moved to Philadelphia to find work along with many other African-Americans who joined the Great Migration to escape the repressive South amid Jim Crow laws (via WBUR).

Although she maintained a close relationship with her relatives, Washington's private life is believed to have been fairly challenging. She was notoriously reclusive, never married, and lived with several women. Today, many believe she was probably a homosexual — at a time when it was still illegal (via the BBC). Despite these personal difficulties, Washington soon became a hero to at least a few avid sports fans in the African-American community. While working as a maid in Germantown, Philadelphia, she joined the YWCA and discovered tennis. Within a few short months, it became obvious that Washington had the kind of natural talent that many tennis pros today can only dream of.

Becoming a tennis titan

Tennis lovers will know that most pros start training very young, developing their talents with monk-like devotion into adulthood. However, in her mid-20s, just one to two years after first playing the sport, Ora Washington had already won 12 doubles tournaments in 1925 (via WBUR). This early blaze of glory reached its pinnacle when she defeated the reigning Black ladies tennis champion, Isadora Channels (via the BBC). After beating Channels, Washington went on to have the most spectacular run of her career, winning back-to-back doubles championships between 1926 and 1936 and back-to-back singles championships between 1929 and 1935.

Commentators from the time noted that she played in an unusual fashion, holding the grip of the racket partway up, and players were said to be terrified of her from the get-go (via USTA). Although some people claimed she had no style at all when she played, it hardly mattered — she almost never lost a match.

Queen of two courts

Despite being a relatively short 5-foot-7-inches, by 1930, Ora Washington had migrated to the basketball court (via WBUR). When she wasn't playing tennis, the athletic all-rounder began dunking baskets for the Germantown Hornets, who — with Washington on their side — became national champions by 1931. Captaining the newly formed Philadelphia Tribunes from 1932 onwards, Washington became a titan in the basketball world, too, and was particularly famous for scoring baskets from the midcourt (via The New York Times).

Playing for the Tribunes earned Washington a real salary, albeit a small one, because the team was sponsored by an African-American newspaper of the same name (via the BBC). Unlike tennis, Black basketball was gaining a serious following at this time, and Ora finally began to appear in white newspapers. As in tennis, Washington was head and shoulders above all the other players on the court, and her team won 11 years in a row at national tournaments.

Missed opportunities

Among a small devoted following in the African-American community, Ora Washington became a legend, dubbed the "Queen of Two Courts" in the Black press (via The New York Times). Her basketball games sold out among a small and loyal following, and those who knew who she was heaped praise upon her. The Chicago Defender once said, "Her superiority is so evident that her competitors are frequently beaten before the first ball crosses the net."

But for all her success, Washington was still keen to prove her mettle against white players. Washington offered to play against the white female tennis superstar of the day, Helen Wills, but sadly, Wills refused. According to The Telegraph, in an interview from 1969, she remarked, "I just hope the day comes when all athletes, regardless of race, can compete against each other and get the recognition they deserve based solely on their ability." The desegregation of sports ultimately proved to be a long slow process, with some sports far ahead of others (via History).

Washington's retirement

Bowing out in the best possible way, Ora Washington retired from singles tournaments in 1938 but returned the following year when people started claiming a new star, Flora Lomax, could have easily beat her (via The New York Times). She went on to disprove the naysayers, defeating Lomax before retiring once again. Washington would continue to play basketball until 1943 and tennis doubles until 1947.

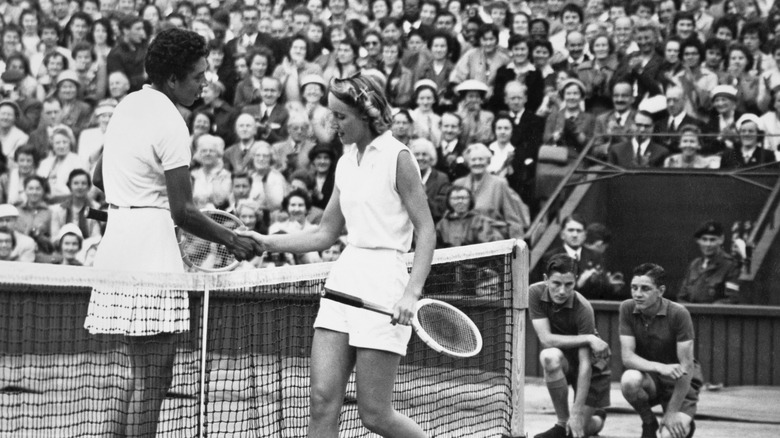

After she left the sport, Washington slowly faded into the background. A rare article published in the Pittsburgh Courier in 1957 celebrated her life and lamented that she was born too late, but it bore the sad title "Fame to Obscurity Marks Life of Net Queen." Just 10 years after Washington retired from tennis, Althea Gibson became the first Black winner of Wimbledon, and she is much better known because she was allowed to compete against white players in the late 1950s (via History). Few people today know that Washington actually beat Gibson in a doubles match before she became famous (via The Washington Post).