Interesting Details About Women's Basketball In The 1800s

The year was 1892. At Smith College in Massachusetts, teacher Senda Berenson was looking for a game for her female students to play when she ran across an article by Dr. James Naismith about his recently-invented game of basketball (via WNBA).

The year before, Naismith was teaching at a school (also in Massachusetts) that trained future YMCA instructors. According to ESPN, he was tasked with creating an indoor sport for his restless male students to play in the winter. Naismith adapted some of his rules from a children's game, Duck on a Rock; this game involved standing on a line and throwing rocks at a cobblestone or boulder that represented the "duck." While ESPN reports that Naismith's students weren't all enthusiastic about the game right away, they soon spread it around the country as YMCA instructors.

When Berenson read Naismith's article, she thought she could adapt this game for women. Because she believed women could easily become tired and anxious, she changed the rules so that female players moved around the court less than their male counterparts, limited to the area designated for their position (i.e., a center stayed in the center). She also limited how long a player could keep the ball and how many times they could dribble it. Despite her belief in women's fragility, she wanted her students to build up their strength through sports so they could compete with men for jobs (via WNBA).

Women's sports in the 19th century

The Sport Journal explains that in the late 19th century, women's sports were generally recreational — not competitive — and typically had no rules. However, some women who wanted competition began to form their own clubs for tennis, archery, croquet, and other sports. Some were affiliated with men's clubs to which women couldn't gain full access. Colleges had sports for women by this time, but most were intramural (so the teams didn't play other schools) or functioned as coed mixers.

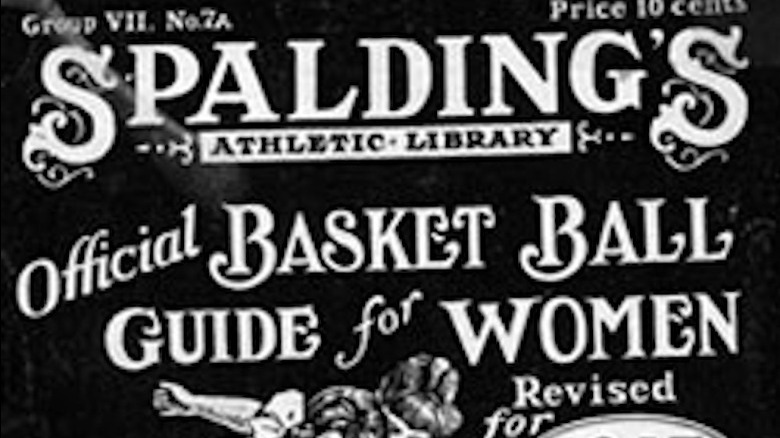

As women's basketball spread around the country, the rules varied. Some places used men's rules; others used Senda Berenson's (via WNBA). The coach at Sophie Newcomb College in New Orleans wrote her own, per ThoughtCo. Berenson's weren't officially published until 1905, forming A.G. Spaulding's "Women's Basketball Guide," but this still didn't standardize things completely (via WNBA). The number of people per team varied. In Berenson's rules, there were six, but when the Executive Committee on Basket Ball Rules wrote its guide for women's basketball in 1905, there could be 6-9 players per team (via Basketball Man).

This lack of cohesion may have happened partially because the game spread so quickly. By 1893, there were women's teams at the University of California Berkeley, Iowa State College, Carleton College, Mount Holyoke College, and Sophie Newcomb College (Tulane) (via ThoughtCo.). Per the WNBA, by 1895, other Seven Sisters schools had established teams: Wellesley, Vassar, and Bryn Mawr colleges.

Earliest known games

Early women's basketball at Smith College remained intramural. ThoughtCo. says the first game there was held on March 21, 1893, and no men were allowed to attend. Sources conflict about the first intercollegiate women's game ever, but it definitely included UC Berkeley, per the WNBA. They played either Stanford University or Miss Head's School, and this most likely occurred in 1896 (via The Sport Journal). No men could attend this one, either, and in fact, ThoughtCo. says women guarded the windows and doors just to be sure. According to Basketball Man, Stanford won 2-1, and each team had nine players.

Per The Sport Journal, many coaches weren't too happy about the introduction of intercollegiate games, and opposition to them continued for a while. Coaches worried they would have less control over their teams if playing other schools. Ironically, Berkeley and Stanford later banned intercollegiate women's basketball games in 1899 (per ThoughtCo.)

The first recorded women's basketball game between two high schools also happened in 1896: it was Chicago Austin vs. Oak Park (via ThoughtCo.).

Early women's basketball uniforms

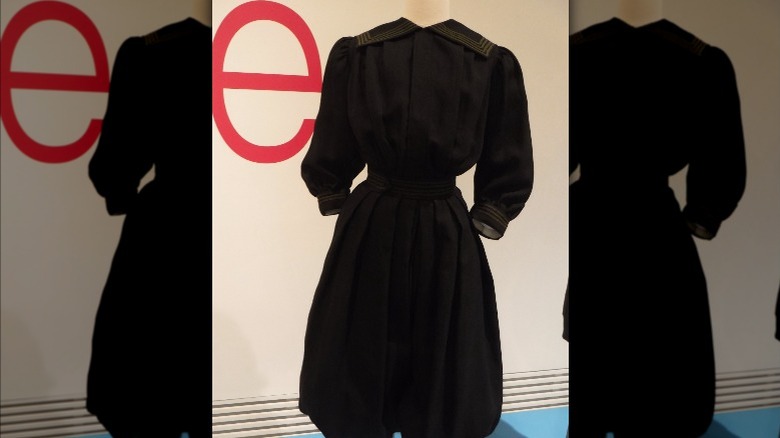

In 1896, Sophie Newcomb College's coach, Clara Gregory Baer, introduced bloomers as part of her team's uniform. Per the WNBA, women had previously been playing in long skirts, which sometimes caused them to trip, fall, and hurt themselves. The WNBA says the shift away from playing in skirts happened partially because of a paper by Dr. Edward Morton Schaeffer condemning corsets. He said they were too confining and bad for women's health. He advocated for wearing "divided skirts" for exercise and pointed out that ancient, Eastern women had worn pants even before men did. According to Schaeffer, men had "stolen" pants from women.

The femininity — or lack thereof — of basketball was debated for generations, and uniforms were always a part of the equation. Amira Rose Davis, an assistant professor at Penn State University specializing in race, sports, and gender, described how this affected the formation of the WNBA. She said (via The New York Times), "There was a lot of this conversation that we've come to really understand in women's sports: 'How can we make it palatable? How can we make it something that we can sell? Shorten the shorts, right?'"

The femininity issue

Early women's basketball raised plenty of controversies, and the question of femininity was always one of the most hotly debated. Senda Berenson wasn't the only one worried that women might over-exert themselves while playing sports. The Sport Journal says that in the 19th century, it was an accepted idea that humans only had so much energy, and using too much of it was bad for one's health. This was believed to be especially true for women, and even more so if they were on their period. Therefore, some doctors and teachers called for the abolishment of women's basketball based on its supposed bad side effects on women's health (via WNBA).

But most of the femininity-in-basketball debate centered around behavior, not health. Early backlash against women's basketball pointed to running, noise, excitement, and nicknames as unfeminine aspects of the game. The Los Angeles Times decried the chasing and hair-pulling in a high school game as inappropriate behavior for young girls. Parents who wanted their daughters to be ladylike stopped allowing them to play.

When the 1905 rule guide was written, it suggested ways of making basketball games more feminine. Berenson proposed the idea of refreshments or after-game dinners. Per WNBA, physical education instructor Agnes Wayman advocated for "neatly combed hair, no gum chewing or slang, never calling each other by last names, and never lying or sitting down on the floor."

The further development of the game

The femininity question continued into the 20th century. In the 1920s, the Women's Division-National Amateur Athletic Federation (NAAF) began regulating women's sports in colleges. They created rules to reduce the competitiveness of women's basketball: limiting awards and travel, discouraging publicity, and encouraging the idea of "play for play's sake" (via The Sport Journal). They did, at least, encourage putting women in charge of their own sports. The Sport Journal reports that women's sports were liberalized somewhat during the 1920s, only to become more conservative again mid-century.

However, women's basketball rules slowly shifted towards being closer to men's rules, per the WNBA. In 1978, women's basketball made it into the Olympics (only 40 years after men's basketball). In 1985, Senda Berenson was the first woman elected to the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame, and in 1999, women's basketball got its own hall of fame (pictured). Finally, in 1997, women got their own professional basketball league (via Women's Basketball Hall of Fame). Slowly but surely, the sport is catching up.