Times Athletes Protested In Very Public Ways

Would you have heard of Colin Kaepernick protesting police brutality if he'd just held a cardboard sign on the side of the road next to a gas station? Probably not. If you want to change the conversation, or perhaps the world, with your protest, you need a massive stage. And like it or hate it, the sheer number of eyeballs drawn to sporting events around the world makes them perhaps the most ideal places for public displays of activism. (People are still talking about Kaep all these years later, right? Case closed).

So as much as certain types of folks want athletes to just shut up and play ball, the fact of the matter is that politics and sports have been intertwined since the beginning. And as long as taking a knee during the anthem or boycotting an event to push for greater equality in a sport gets attention and, you know, works, that relationship isn't likely to change any time soon. In some cases, after all, protests by athletes have had profound impacts on their sports and the world they play in. Some displays of activism in sports have even become enduring symbols that inspire millions, decades after the fact.

From Bill Russell and the Celtics pulling out of a 1961 game in Kentucky over racism to Billie Jean King scaring the powers-that-be into paying female tennis players as much as men, these are some of the most famous, and important, protests ever undertaken by professional athletes.

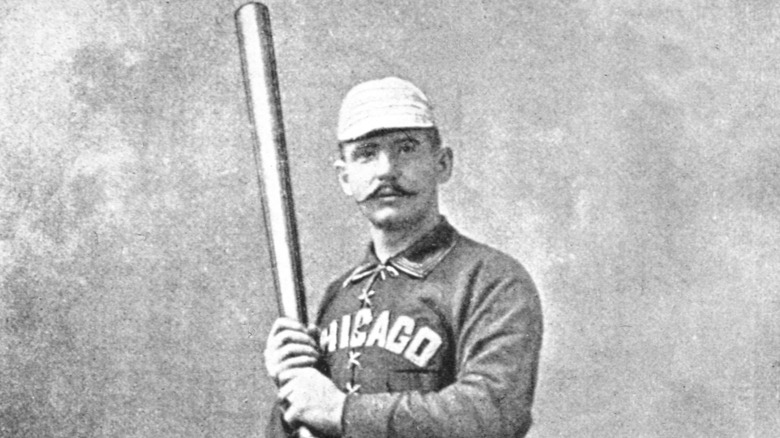

Cap Anson

Lots of folks think of protests in a positive light. Even if you disagree with the method, everyone can agree that racial equality, or equal pay for female athletes, for example, are good causes.

But not all protests are quite so noble. Enter Adrian Constantine "Cap" Anson. According to the Baseball Hall of Fame, the late 19th-century ballplayer was a pioneer who revolutionized how the sport was organized and played. For over two decades, he held numerous league records, retired from professional baseball in 1897 at age 45.

But as the article also points out, he championed segregation in baseball. Writing for the Society for American Baseball Research, David Fleitz says that Cap threatened to sit out an 1883 exhibition game in Ohio, because the opposing local team had a Black player: catcher Moses Fleetwood Walker. He relented on this one occasion when faced with the financial loss a last-second cancellation would bring, but he wasn't done crusading against racial equality in the sport. Four years later, in 1887, Anson again protested the other team's inclusion of a Black player (pitcher George Stovey). Within a few years, the MLB would rally behind Anson's objections, and no African-Americans were playing professional baseball.

Jackie Robinson is often credited with being the first Black man to play professional baseball. This is untrue — Walker and Stovey were — but the color barrier Robinson became famous for tearing down was disgracefully built by Cap Anson.

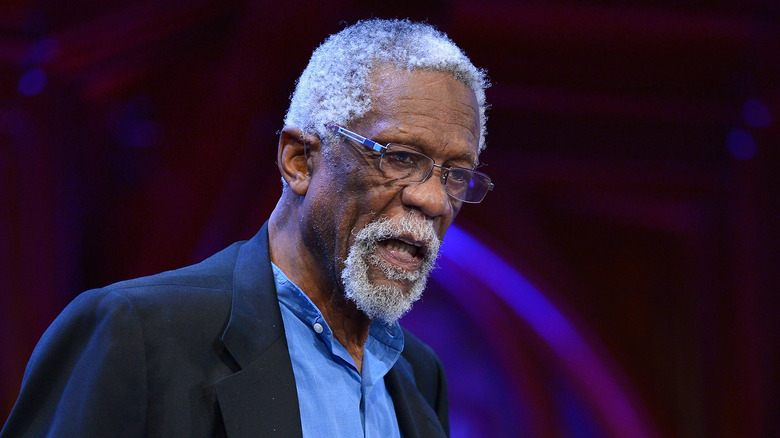

Bill Russel and the Celtics

Bill Russell is one of the biggest legends in basketball history. But that's his reputation now. When his career was just taking off, a Black man playing in the 1960s wouldn't have an easy time of it no matter how good they were. This was a time when African Americans could expect drastically different receptions depending on what part of the country they were in. In the northern or coastal states, they might not get more than a few nasty stares. But head too far south, and things could get much uglier.

In 1961, The Washington Post says the Celtics arrived in Lexington, Kentucky, for an upcoming game against the St. Louis Hawks. Unfortunately, they were coldly received with numerous displays of exactly the kind of overt racism that were driving the then growing civil rights movement. Sam Jones and Thomas "Satch" Sanders, for example, were told by staff in their hotel coffee shop that, "Well, we really can't serve you people" (via WBUR).

Led by Russell, the Black players on the Celtics — and even two from the Hawks — sat out the game in protest. The next day, Russell informed the press, according to Mark Bodanza's "Ten Times a Champion: The Story of Basketball Legend Sam Jones," "We've got to show our disapproval of this kind of treatment or else the status quo will prevail. We have the same rights and privileges as anyone else and deserve to be treated accordingly."

The 1965 All-Star boycott

In 1965, Sports Illustrated says the Oakland Raiders had barely touched down in New Orleans when they were met with harsh racism by locals. While white players were able to find cabs with ease, Black players were stranded at the airport for hours because taxis were unwilling to give them a ride. They faced further overt discrimination from hotels and businesses around town, including one incident when a bouncer pointed a gun at a Black player who tried to enter his club.

Even though the Civil Rights Act had been passed, prohibiting businesses from racial discrimination, some local businesses had only integrated — and not peacefully — a few weeks prior to the Raiders' arrival. And their owners were under no obligation to like it. In addition to racism from locals, the players were informed that although Tulane Stadium had just hosted a racially integrated Sugar Bowl game for the first time a mere 10 days earlier, the AFL All-Star game would have segregated seating.

This was the final straw. Numerous Black players, and some white ones, voted to boycott. The game was ultimately moved to Houston at the last minute.

According to Pro Football Hall of Fame, the unprecedented episode ended up being a good thing for New Orleans in the long run. It so embarrassed the city and spooked businesses who feared further income loss from future incidents, that they cleaned up their act in record time. A year later, enough had changed that they got a franchise of their own: the New Orleans Saints were born.

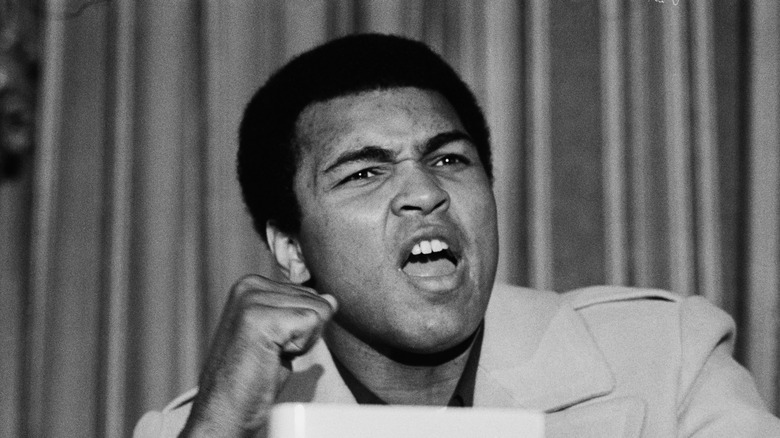

Muhammad Ali

The 1960s weren't just tumultuous for America because the old racist social order was being challenged in unprecedented ways, leading to demonstrations, rapidly changing laws, riots, and deeper cultural divides than at any point since the Civil War. It also happened to be when the controversial Vietnam War broke out, which also led to demonstrations, cultural divides, and riots. Yikes. Imagine being a Black person in the middle of all that. Worse still, imagine being a famous Black person with microphones and cameras in your face at all times.

This is the situation boxing superstar Muhammad Ali found himself in when he learned he'd been picked for the 1967 draft. According to History, Ali defied the law and refused to enlist, citing his Muslim faith and famously saying, "I ain't got no quarrel with those Vietcong."

Legally speaking, the case was open and shut. On June 20 of that year, History says he was slapped with a $10,000 fine (a lot more back then than it is today, and that's saying something) and sentenced to five years in prison. Ali could fortunately afford to hire good lawyers, who appealed the case and at least got him out of jail time. But he wasn't able to avoid being banned from boxing for three years when he was nearing his prime.

Still, it didn't stop him from dominating the sport when he returned to the ring in 1970. The following year, the Supreme Court overturned Ali's conviction.

Kathrine Switzer

It was widely known that the Boston Marathon was for men only. Thing is, the sexists who organized the race in the 19th century forgot to explicitly state as much in the rulebook. You can see where this is going.

In 1966, Syracuse student Katherine Switzer was jogging in the New York snow when a university mailman and 15-time Boston Marathon vet Arnie Briggs took her under his wing. Briggs frequently discussed the Boston Marathon during their practice jogs, finally prompting Switzer to say, according to her book, "Marathon Woman: Running the Race to Revolutionize Women's Sports," "Oh, let's quit talking about the Boston Marathon and run the damn thing!"

It took some convincing, but Briggs ultimately agreed to back her up after she proved during a 31-mile run that despite being a woman, she was perfectly capable of tackling a measly 26. The next year, Switzer and Briggs joined the Boston Marathon. Cleverly, Switzer signed up as "K. Switzer" to avoid outing herself as a woman, correctly confident that nobody would notice the irregularity in a contest with well over 700 entrants until the race was already underway.

Although some tried to protest, Switzer writes, most of the reception was positive. Soon, the press realized a woman was running, and news reports were dominated by the story. Although their inclusion was never explicitly prohibited, Switzer's participation moved the Boston Marathon to officially allow women into the race starting in 1971, as per the Boston Athletic Association.

Tommie Smith and John Carlos

Several photos are in the running for most iconic images of the 20th century. Raising the flag on Iwo Jima. The VJ Day Times Square kiss. Migrant Mother. Tank Man. But one that deserves a mention is of two Black American Olympians — sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos — raising gloved fists into the air on the awards podium in 1968, according to History.

You might think that because it was during the height of the civil rights movement, months after Martin Luther, King Jr. had been assassinated, that this was directed at white supremacy in America. And you'd be right, but that's not the whole picture. The sprinters, who had placed first and third in the 200 meter race, were members of the Olympic Project for Human Rights — an organization that nearly boycotted the '68 Olympics in protest of threatened Black rights around the world. A non-American issue they, and therefore Smith and Carlos, campaigned against, for example, was that of racial apartheid in South Africa.

In fact, according to Civil Rights Teaching, the disinvitation of South Africa to the Olympics was one of the OPHR's primary goals, alongside other demands such as the hiring of more Black coaches and the restoration of Muhammad Ali's heavyweight title, which was stripped from the boxer after he protested the Vietnam draft the year before. Therefore, Smith and Carlos were also protesting the war, although through the lens of advancing human rights for oppressed Black people.

Billie Jean King

It's depressing but not surprising to know that the fight to close the gender pay gap in sports has been going on for decades. At least things used to be a little more overt and obvious. Luckily, women in the tennis world had one Billie Jean King fighting the good fight. In 1970, History says she pocketed a measly $600 after a victory, while male winner Ilie Nastase got $3,500. When she won her first Wimbledon tournament in 1966, she received just over $1,000, while Rod Laver pulled in just under $3,000. These were just two of the many injustices that inspired her to act.

"Everyone thinks women should be thrilled when we get crumbs," she famously remarked, "and I want women to have the cake, the icing, and the cherry on top too."

But it wasn't just the pay — History says that King and other women tennis players were faced with fewer and fewer places in which to compete, whereas men had no such shortage of career opportunities. She and the other eight female members of the "Original 9," as it came to be known, decided to do something about it — by forming their own tournament. When that didn't put an end to the pay gap, King formed the Women's Tennis Association in 1973 and threatened to boycott the 1973 U.S. Open. Finally, the powers that be caved, agreeing to pay men and women the same prizes moving forward.

The Gay Games

"There were Rat Olympics, there were Xerox Olympics, there were Police Olympics," said Shamey Cramer, a swimmer and leader in San Francisco's inaugural 1982 Gay Games, according to History. "You could have an Olympics for anything, but heaven forbid you should be gay or lesbian."

That year, many gay athletes wanted to protest against stereotypes and showcase the fact that they could be athletic and deserved recognition. Olympic veteran Tom Waddell — who'd been present at the 1968 Olympics where Tommie Smith and John Carlos had stunned the world by throwing gloved fists into the air on the awards platform (which inspired Waddell) — threw the Gay Olympics together on a budget of $220,000. It was a miniscule amount even at the time — especially for a star-studded event with 1,300 athletes. Gay and lesbian athletes weren't confined to the dingy bars that allowed them to compete in bowling and billiards. For the first time, they could compete in the open.

However, the United States Olympic Committee successfully sued the organization, barring it from using the word "Olympics" in the title. But although it wouldn't be called the "Gay Olympics," as was the original plan, the "Gay Games" went off without a hitch that year. Plus, that lawsuit only strengthened support for the event, according to History.

It was a watershed moment for LGBTQ+ representation in sports. "When I walk into the [Gay Games] opening ceremonies," competitor James Hahn later remarked, "I always get that sense of history coming back."

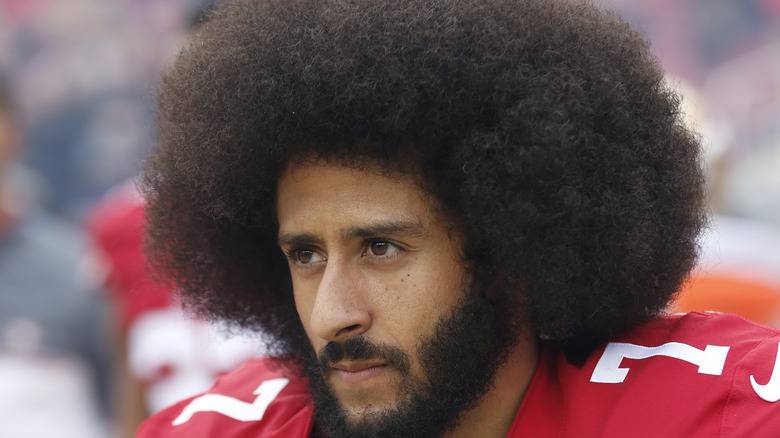

Colin Kaepernick

In 2016, San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick took a knee during the national anthem, to protest police brutality against African Americans. Unless you've been living under a rock, you know what happened after one of the most famous acts of protest in history. Kaepernick was muscled out of the NFL and was simultaneously vilified by conservatives for desecrating the anthem and lionized by the left for taking a moral stand at great cost to his own career.

"I'm not anti-American," Kaepernick said, according to The Washington Post. "I love America. I love people. That's why I'm doing this. I want to help make America better." But many weren't buying it. Despite then-President Barack Obama expressing support for Kaepernick's first amendment rights, the quarterback was embattled. He finished the season with a record of 2-14 and didn't renew his contract, making himself a free agent. However, the Post article claims that when Kaepernick was suspiciously absent from the list of subpar quarterbacks who found work with other teams the next season, rumors he was being blackballed by the league began to swirl.

After becoming the face of a Nike ad campaign, Kaepernick became a hated figure for some and an enduring symbol of the fight against racism and police brutality in America for many others. At the height of the Black Lives Matter protests following George Floyd's murder, NFL commissioner George Goodell claimed the league was wrong for not being more supportive of its players, according to another Washington Post article.

Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf

Once a rising star for the Denver Nuggets, Abdul-Rauf is mainly known today for kneeling during the national anthem in 1996.

"I became a Muslim... we're taught in so many ways that you can't be for God and oppression at the same time," he said in an interview with NPR. "And I began to view the American flag, with what I was reading, you know, with just — not just domestic but foreign policy that it was against my belief system, and it was against my principles. And so I didn't want to acknowledge that symbol that represented that."

Sadly, but predictably, Abdul-Rauf was vilified by the press and drummed out of the NBA, as per The Guardian, which says he was suspended in March of that year and fined nearly $32,000. He would never return.

In the NPR interview, Abdul-Rauf says he knew what he was getting into. "Reading history and knowing what had happened to the likes of Muhammad Ali and John Carlos and Tommie Smith and all of these others, I knew that this was not going to end well as long as I continued to articulate the things that I'm articulating. But I was good with that." When Colin Kaepernick took an identical stance and met the same fate, Abdul-Rauf sent his support. "He said 'this is the most free I've ever felt in my life.' I said, 'I understand exactly what you're saying," said Abdul-Rauf.

The Iranian Men's football team

On September 16, 2022, Newsweek says that Mahsa Amini, a 22-year old Kurdish woman who was arrested by Iran's morality police for failing to wear a required head covering, died in custody. Shortly after, protests against Iran's regime consumed the country while the world watched. Other demonstrations took place around the globe in solidarity with those risking their lives in Iran. Predictably, NPR says the government's response has been brutal, leading to the deaths of hundreds of demonstrators. As of now, neither side shows any sign of backing down.

2022 also happens to be a World Cup year. Another NPR article says Iran's men's team protested the brutality back home by staying silent while their national anthem was played, before their first game against England. The article also quotes several players as expressing support for the protestors and disappointment with the regime.

Sadly, but again quite predictably, CNN says Iran's theocratic government threatened the families of the players if they made any further demonstrations before the next kickoff. At the next game, the players had no choice but to sing along. Iran has also expressed outrage at the U.S. Men's team for changing the Iranian flag on their social media posts in solidarity with the protesters, as per CNN. However, despite calling for the U.S. to be disqualified, it was America that sent Iran home with a 1-0 knockout win on November 29, according to The New York Times.