Chilling Details About These Famous Corpses

If you want your 15 minutes of fame, you generally have to get it while you are still alive. It's a rare thing for a random nobody to die and only then become famous, purely because of something that happens to their body after they are gone.

But occasionally, this does happen. Even weirder, sometimes you have famous people who got their fame the old-fashioned way – while they still had a pulse – who then died and became even more famous for something their corpse did. It's a real kick in the teeth for anyone trying to become a YouTube star that some dead bodies are doubly successful in the celebrity department.

So how, exactly, can a dead body do something so notable that it becomes a household name? We don't like to think about it, but weird stuff happens to corpses pretty often, whether it's falling out of the casket at the funeral or being part of wacky adventures at a beach house. So to find true fame as a dead body, something really unique has to happen. Here are chilling details about these famous corpses.

Eva Peron

If all you know about Eva Peron, the former first lady of Argentina, you learned from the stage musical and/or film "Evita," you are aware she died tragically young of cancer, but what happened to her after that might surprise you. For some reason, no one thought to make a sequel to the musical where Eva's widower Juan Peron and his third wife, Isabel, dance around her body, singing about how they will make her pretty again.

But that is, in fact, what happened (minus the singing and dancing, one assumes). After Eva died, Juan was removed from the presidency by a coup, according to BBC News. These same coup plotters stole Eva's body and it began a strange journey that included time in government buildings, a van, and a purposely mislabeled grave in Italy. Finally, the body was disinterred from there and returned to Juan, who was living in Spain at the time. Reunited with his wife's body after 16 years, as The New York Times reported at the time, he kept it in his home.

Carlos Spadone was there when the body was delivered. "General Peron, the gardener, and I took the body out of the coffin," he later recalled. "We lay it on a marble-topped table. Our hands got dirty from all the earth, so the body had to be cleaned. Isabel took care of that very carefully with a cotton cloth and water. She combed the hair, and cleaned it bit by bit, and then blow-dried it. It took several days."

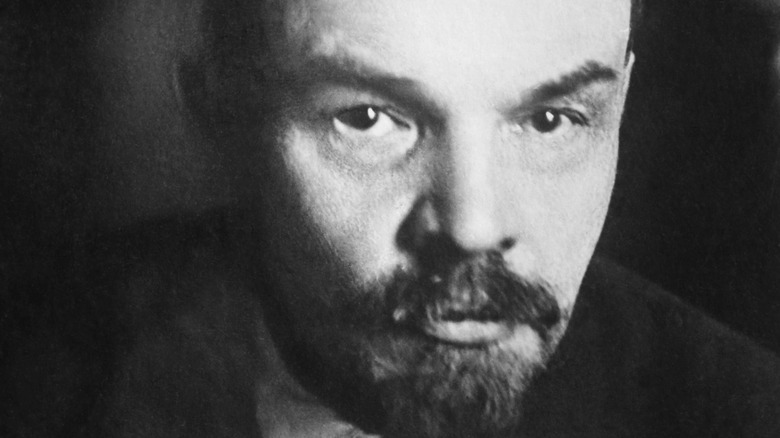

Vladimir Lenin

Dictators have many things in common, but one of the strangest traits seems to be their desire (or that of their subjects) for their bodies to be displayed long after the strongmen are dead. Mao Zedong, for example, is on display in Tiananmen Square to this day, per the BBC. Perhaps his people got the idea from the Soviets, who had embalmed their leader Vladimir Lenin and put him on display decades before.

Lenin's biographer Robert Service explained this seemingly bizarre decision (via Macalester College): "Lenin was not merely to be depicted as a heroic figure in the history of Bolshevism ... he had to enjoy the mythic status of an omniscient revolutionary saint."

But the thing that makes many saints' bodies special is their incorruptibility. This meant that to make Lenin's body give off the impression it didn't rot, a lot of work was going to have to go into preserving it, per PBS NewsHour. And not just at first, like you might expect, with similar embalming techniques as you get with your standard funeral. The body really wants to decay, so even decades later, experts are brought in to freshen him up occasionally. "They have to substitute occasional parts of skin and flesh with plastics and other materials, so in terms of the original biological matter, the body is less and less of what it used to be," says Alexei Yurchak (via Scientific American), a professor of social anthropology at UC Berkeley. Who knew a body could present the same problem as the Ship of Theseus?

Saint Bernadette of Lourdes

St. Bernadette of Lourdes started out as a young peasant girl in France, but her life changed forever in 1858, when she told people about her visions of the Virgin Mary, according to Artnet News. If you've ever heard of people taking pilgrimages to Lourdes, these visions, and an associated spring said to heal illnesses, are the reason why.

Little Bernadette was suddenly world-famous, but she hated the attention. After hiding out in a nunnery, she decided to become one herself, per Britannica. Sadly, Sister Bernadette hadn't been well for some time and would die of tuberculosis in 1879, aged just 35.

However, miracles associated with Bernadette continued after her death, which meant she was eligible to be canonized. Atlas Obscura records that the long process of becoming a saint involved some slightly odd requirements, including exhuming her body three different times between 1909 and 1925. Fortunately for those who had to do this deed, the woman who had been very pretty in life was, somehow, still unexpectedly pretty decades after her death. A doctor who was present the second time her body was dug up in 1919 wrote, "The body is practically mummified, covered with patches of mildew and quite a notable layer of salts, which appear to be calcium salts ... The skin has disappeared in some places, but it is still present on most parts of the body." This was good enough for the church, who decided Bernadette's body was "incorrupt," made her a saint, and put her on display for pilgrims to visit.

The Soap Lady

The Mütter Museum of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia (pictured) is famous for its strange collection of objects, many of which are not for those with a weak stomach. But perhaps none is as deeply affecting as the corpse of a woman known as "The Soap Lady." A former curator of the museum described the corpse as "one of the most revolting objects that can be imagined" (via Penn Museum). Despite this, he and other curators know that the public like looking at weird things, which is why they have kept her on display almost continually for a century and a half.

You can still see her today, in a glass case, with her face twisted into what appears to be a terrified scream. Her eyes are sunken in, and her toes are pointed. Her most noticeable feature, however, and what earned her the "Soap Lady" nickname, is the coating all over her body. Called saponification, it occurs when the fat in a body goes through a very rare process and becomes a dark wax on the outside of the skin. Gerald Conlogue, a professor at Quinnipiac University told WIRED, "What we may be looking at is a shell or casing made out of this soapy substance sealing out the outside environment."

While the corpse was originally labeled "The woman named Ellenbogen," other details – like her age and when she died – have been proven wrong over the years, according to the Mütter Museum, so sadly, she is still unidentified after all this time.

Xin Zhui

According to History Daily, the tomb of Li Chang, the Marquis of Dai, was discovered completely by accident during the construction of an air raid shelter in China in 1971. It was an astonishingly important and extensive archeological wonder – and then the team found the body of Xin Zhui. Also known as Lady Dai, she was the marquis' wife. Although she'd died well over 2,000 years before, her body was in remarkable shape.

One scientist told China Daily (via Indiana Public Media), "The body is so well preserved that it can be autopsied by pathologists as if it were only recently dead. When Lady Dai was found, her skin was supple and her limbs could be manipulated; her hair was intact; her type A blood still ran red in her veins, and her internal organs were all intact." While that all sounds amazing, the thing most viewers would care about – her face – did not look so great, as it was swollen to an unnatural size and shape.

It's not clear exactly how her body was in such a good state of preservation after more than two millennia, but scientists have theories. The corpse might have been covered in acid or mercury, which would have killed the bacteria that would normally deal with a dead body. And she was further protected thanks to layers of silk and a matryoshka-doll-like system of nesting coffins.

Jeremy Bentham

Many times, people whose bodies are displayed after they died didn't actually request the strange honor. For example, Mao Zedong specifically asked to be cremated, before his wishes were ignored, and his body was put out for viewing. However, Jeremy Bentham knew what his wishes were after death and he was going to get them, even if he wasn't an all-powerful dictator. Bentham had always been a weird guy, especially for his time. The Times Literary Supplement describes the philosopher, who died in 1832 at age 84 (per Britannica), as a "republican, radical, feminist and gay rights advocate."

However, his wishes for his corpse, outlined in his will shortly before he died, took his quirkiness to a new level. Bentham instructed (via UCL), "[My] skeleton ... [will] be put together in such a manner as that the whole figure may be seated in a chair usually occupied by me when living, in the attitude in which I am sitting when engaged in thought in the course of time employed in writing. ... the skeleton [is] to be clad in one of the suits of black occasionally worn by me." He then gave specific instructions for this "auto-icon" being put on display.

And so it was, eventually ending up at University College London, where, Londonist reported, it was moved to an even more conspicuous location in 2020: A glass case in the Student Center. The university explained in a statement, "Bentham's new home provides greatly enhanced preservation conditions, better visitor access, and a place at the center of the student community."

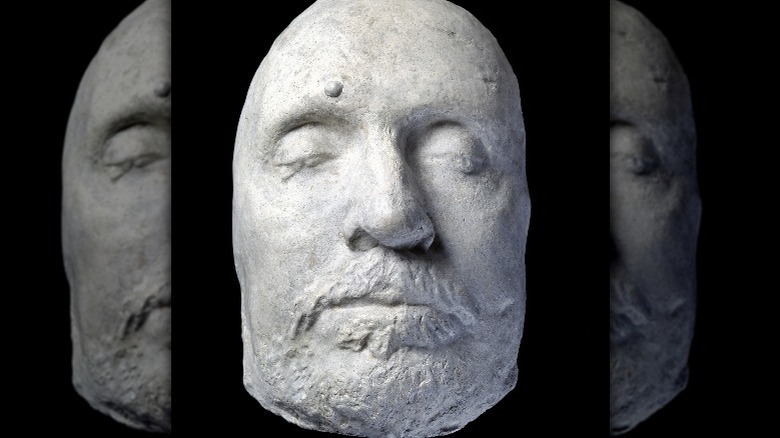

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell was the member of parliament in the middle of the 1600s who was most instrumental in ending the monarchy – at least temporarily – with the execution of Charles I. Cromwell would go on to become Lord Protector and managed not to be executed himself, instead dying of a variety of illnesses aged 59 in 1658, according to Royal Museums Greenwich. He was given a prime burial spot in Westminster Abbey alongside a king, and while his actual burial was incredibly simple in keeping with his Puritan belief, a large public funeral service without his body was also held.

When Charles II, son of Charles I, was returned to the throne in 1660, he was not thrilled with the guy who had effectively killed his dad, as you might expect. So the king threw Cromwell out of the Abbey, and had his corpse hanged and beheaded, just for good measure. Then his head went on a pike for all to see.

Eventually, heads displayed that way will fall off, and this is where the story of Cromwell's corpse gets really weird. According to Sky History, the story goes that a guard took the head when the wind finally knocked it down. Then the trail goes cold for a while, until the head turned up again in the early 1700s and was passed around between collectors. One of them even liked to take out Cromwell's head and show it to guests. Eventually, the head believed to be Cromwell's was buried in a semi-secret spot at Cambridge University, per Westminster Abbey.

Percy Shelley

The romance of Percy and Mary Shelley was one for the ages, according to The Rosenbach Museum & Library. They endured a huge amount of personal problems, including debt and deaths, hung out with cool celebs like Lord Byron, and wrote some great poems and novels while they were at it. And they did it all before they turned 30 – in fact, Percy Shelley did literally everything before he turned 30, since he died in a boating accident at 29. His widow Mary was only 25.

In keeping with the gothic tone of the woman who came up with "Frankenstein," after Mary died, it was discovered she'd kept her husband's heart in her desk for decades. Very unusually for the time, Percy was cremated — except after the funeral pyre on the beach was extinguished, his mostly-undamaged heart was discovered in the ashes. Edward John Trelawny was there and said he pulled it out himself. His theory for why the heart didn't burn (via Snopes), was that "in all cases of death from suffocation the heart is gorged with blood; consequently it is the more difficult to consume, especially in the open air."

But there's a possibility Mary might unknowingly have held on to something far less romantic: Percy's liver. According to 19th-century reporting (via Digital Dying), "The heart, being hollow, is easily destroyed, while the liver, which is the most solid mass of the internal organs, resists most intense heat. ... Shelley's liver was saturated with seawater, and was on that account more than normally incombustible."

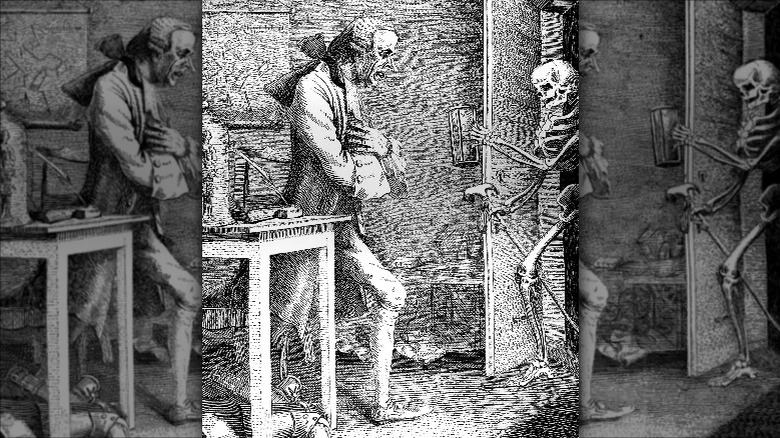

Laurence Sterne

Laurence Stern's name might not be as familiar as that of his most famous creation, Tristram Shandy, the eponymous narrator and hero of Stern's most famous (and notably strange) novel. Stern wrote many other works as well, and was a member of the clergy in the Church of England, according to Britannica. He died in 1768, aged 54.

Unfortunately for Stern, the 18th century was the high point of body snatching, and being a famous author was no protection from the "resurrectionists" who dug up freshly buried bodies and delivered them to medical men for dissection. Stern's corpse was exhumed from a graveyard in London and delivered to Charles Collignon, an esteemed professor of anatomy at the University of Cambridge, according to an article in the Journal of Medical Biography. While for a long time this strange event was thought to be just a legend, Britannica says it was finally proven in 1969.

While bodies were stolen and used in anatomy classes all the time, the students were probably surprised to see a famous face. Even before the internet, enough people knew what Stern looked like that he was recognized, with reporting at the time (via "A Culture of Mimicry: Laurence Sterne, His Readers and the Art of Bodysnatching") that "the marked features of the great humorist" led to his identification during a lecture, while the contemporary scholar Edmond Malone claimed, "A gentleman who was present at the dissection told me he recognized Stern's face the moment he saw the body." Thanks to his famous face, Stern would be returned to his grave.

Ted Williams

The baseball player Ted Williams was interested in the idea of being frozen and reanimated after death through cryonics ... or rather, he might have been. The drama surrounding his death and whether he actually wanted to be cryonically preserved led to a court case that tore his family apart, according to the Las Vegas Sun. Eventually, Williams' corpse was preserved at the Alcor facility in Arizona. But years later, Williams was back in the news with even more drama. Former employees of Alcor came forward to talk about some less-than-acceptable things they alleged went on at the company, including how Williams' corpse was treated.

For example, his head was separated from his body, as was standard, but then things got weird. "They want the heads resting on something, not just setting at the bottom of the stockpot," said Cindy Felix, a former Facilities Operations Manager at Alcor, via Deadspin. The chosen headrest? A tuna can. And when it was discovered Williams' head was stuck to the can? Well, according to Larry Johnson in his book "Frozen: My Journey Into the World of Cryonics, Deception, and Death" (via ESPN), he watched as another employee "grabbed a monkey wrench, heaved a mighty swing, missing the tuna can completely but hitting the head dead center. Tiny pieces of frozen head sprayed around the room."

The company, perhaps not surprisingly, released a statement saying, "Alcor denies allegations reported in the press that there was mistreatment of the remains of Ted Williams at Alcor."

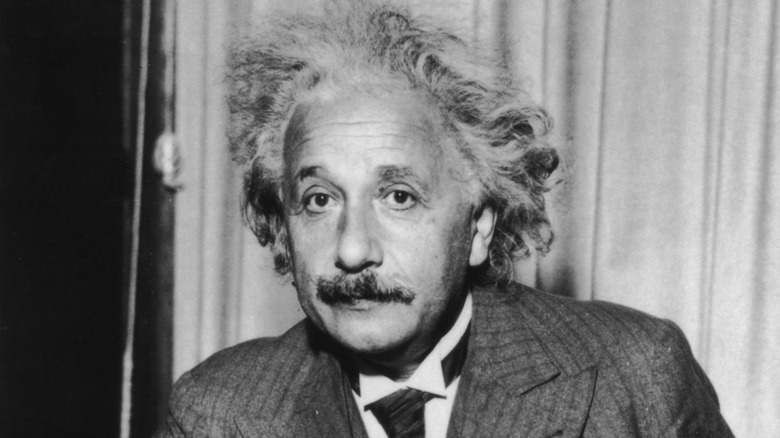

Albert Einstein

You can see why people, even scientists who should know better, might think Albert Einstein's brain was special – and not in a metaphorical way, but in a "we should study this" way. For one scientist, the pathologist who did the genius' autopsy when he died in 1955, according to the ANU Museum of the Jewish People, this presented a moral quandary. You see, Einstein had stated in his will, "I want to be cremated so people won't come to worship at my bones." This is a perfectly fair wish for anyone, let alone one of the greatest scientists ever. But ... surely a brain doesn't count as a bone? And wouldn't studying this great mind be worth it, for science?

So pathologist Thomas Harvey left work that day after autopsying Einstein's body with the scientist's brain in a cookie jar. If you think this would be impossible to keep a secret for long, you would be right. In "Postcards from the Brain Museum" (via National Geographic), Brian Burrell explains, "When the fact came to light a few days later, Harvey managed to solicit a reluctant and retroactive blessing from Einstein's son, Hans Albert, with the now-familiar stipulation that any investigation would be conducted solely in the interest of science."

It wasn't until 1995 that the brain was taken on a cross-country road trip to be returned to its next of kin. The man who drove Harvey remembers it well, saying, "He brought out his bags, and in one bag, he had a Tupperware container in which he had stashed the brain."