George Thomson Won A Nobel Prize By Disproving His Own Father's Theory On Electrons

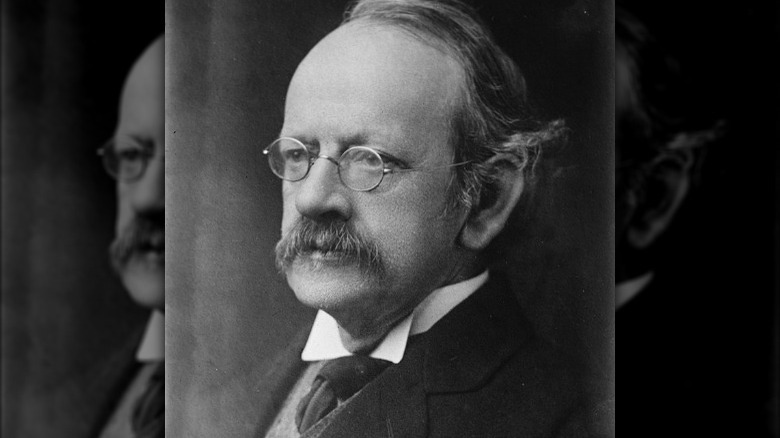

Not many people come up with revolutionary new scientific concepts that fundamentally change the way we understand our world, and even fewer people get the chance to do it by disproving their own father's theory, but Sir George Paget Thomson (above) was one of those rare individuals. His theories about electrons, the tiny particles that orbit around an atom's nucleus, did just that (via Chemistry World).

Sir George's father, Sir Joseph John Thomson, was a well-esteemed chemist and physicist. During his time as a scientist, Sir Joseph was looking to settle a debate that had been going on in the scientific community for many years, and it had to do with electrical currents, specifically cathode rays. These rays are produced when a tube has all the air or other gaseous material removed from the space, and an electrical current is sent through. Some physicists proclaimed that this electrical current was created by a substance called the ether, which was believed to be existent through all forms of space. However, other scientists believed them to be particles, and that's where Sir J.J. Thomson came in to solve the issue (via Britannica).

Particles or waves?

Originally, cathode ray tubes were sealed glass tubes with no air, and two electrodes on one end of the tube. These electrodes were oppositely charged from one another, and were known as the cathode and the anode. The cathode was negatively charged, whereas the anode was positively charged. A high voltage sequence is then sent to both electrodes, and a ray beam starts from the cathode, flows through the anode, and eventually hits the other end of the tube, where it would interact with something called phosphors, which glowed when the ray hit them, according to Khan Academy.

Sir Joseph John Thomson (above) improved a way of measuring the ray, which would settle the debate on what they actually were. Sir Joseph added two oppositely charged plates inside the tube. The plates would hover above and below the ray. Since the ray originated from the cathode, it had a negative charge, and therefore it would gravitate toward the positively-charged plate — so the theory went. If this happened, it would help support the theory that cathode rays were made of particles, settling the debate once and for all (via Khan Academy).

Turns out they're ... both?

Sir Joseph John Thomson's theory worked, and electrons were almost indisputably particles. He was awarded a Nobel Prize in physics in 1906. Case closed, and everyone was happy. Kind of ... well, sort of ... actually, not really. Years later, Thomson's own son, Sir George Paget Thomson, came in to radicalize the theory even further. These particles, named electrons, weren't just particles, and they also weren't just waves. Turns out they were ... both? In 1927, George Thomson observed an electron beam pass through a nickel crystal, and watched diffraction patterns occur, which utterly changed what scientists thought of electrons (via Nobel Prize).

Diffraction is when wavelengths bend around an object when they interact with it, and given how George Thomson proved electrons to do this, scientists were fascinated about how these unique particles behaved in this manner (via Evident). What this showed, however, was that electrons travel through the universe like a wave, but still somehow interacted with different objects as a particle (via The Conversation). George Thomson was awarded his own Nobel Prize in physics in 1937. This exciting discovery has allowed scientists to develop many of the technologies we enjoy today on a daily basis. Our world would be fundamentally different if the Thomson family had not contributed what they did to science.