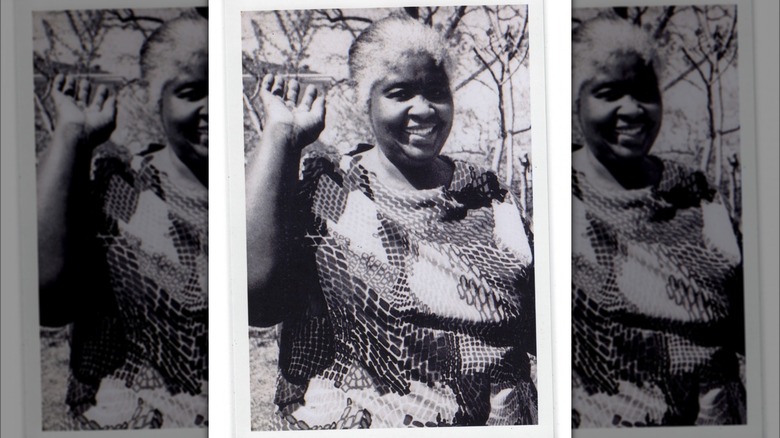

Meet Georgia Gilmore: The Cook Who Fed The Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s is filled with memorable names: Martin Luther King Jr., Medgar Evers, Rosa Parks, and countless others (via WNYC Studios). But one name you might not have heard of from this period in American history is that of Georgia Gilmore, a Montgomery, Alabama cook who worked tirelessly behind the scenes. You see, any political or social movement is going to require more than just the public face (viz, marches and boycotts) that brings attention to the cause. It's going to take money, logistical planning, and on a more practical level, the protestors are going to need food. That's where Georgia stepped in: she cooked for the protestors and raised money for the movement with her craft.

Gilmore didn't go it alone, however. As NPR reports, her activities inspired other women to do the same thing, and the women coalesced into a club of sorts: the Club from Nowhere, a name chosen deliberately for its ambiguity. Gilmore kept it up until the very end: She literally died in the kitchen while cooking — for protestors at a march, no less.

'Georgia Gilmore Didn't Take No Junk'

The perilous and volatile situation in which Blacks lived during the Jim Crow era, particularly in the Deep South and places such as Montgomery, Alabama, hardly needs explaining here. However, in a larger sense, many Black people in those days, especially the poorer ones, were effectively at the mercy of whites. White-owned businesses could fire Black workers and then blacklist them, effectively preventing them from being hired more or less anywhere else in town, as John T. Edge explained to NPR. White people also owned the land and homes the Black residents would rent, and if the landlord took exception to what their renter was doing, a Black person involved in a protest movement could find themselves homeless.

Georgia Gilmore, however, was not prepared to tolerate any guff from anyone. "Everybody could tell you Georgia Gilmore didn't take no junk. You pushed her too far, she would say a few bad words. You pushed her any further, she would hit you," Al Dixon said, via NPR. However, she was also smart, and she and others in the movement knew that secrecy and outfoxing the establishment would be the order of the day. And when the Montgomery bus boycott got going, she used cooking as a cover for her activities.

A Pre-Boycott Boycott

The Montgomery, Alabama bus boycott of 1955-1956 officially began in December 1955, after Rosa Parks famously refused to move to the back of the bus for a white man (via NPR). However, Black activists had been angling for a boycott of the Montgomery system before Rosa Parks due to the abuses within the system that went far beyond just forcing Black people to move to the back of the bus for whites (per Montgomery Advertiser). Blacks would be forced to vacate the bus, for example, to make room for white passengers, and would not get their money back. Oftentimes, drivers just sped off once a Black passenger had paid their fare, and in one incident that led to the death of the would-be passenger.

Georgia Gilmore, a midwife and cook, was one of the people who had paid her fare only to have a driver drive off without allowing her onto the bus, which caused her to invoke her own, one-woman boycott of the system. In a trial during which Martin Luther King Jr and other activists were facing charges of unlawful conspiracy, Gilmore testified about this mistreatment. "When I paid my fare and they got the money, they don't know Negro money from white money," she said (per NPR).

Georgia's Activism Cost Her Dearly

As mentioned previously, Black people in the Jim Crow era could find themselves unemployed and homeless if they ran afoul of whites, and that's exactly what happened to Georgia Gilmore, according to Mental Floss. After she testified on behalf of the organizers of the Montgomery bus boycott, her employers at the whites-only cafeteria where she worked fired her and blacklisted her.

Georgia effectively turned into a freelance cook, and indeed, her house kitchen became a sort of ersatz headquarters for the civil rights movement. Martin Luther King Jr. would hold meetings at her home, and rumor has it that Lyndon B. Johnson and John F. Kennedy ate there, according to Equality Archive. "Her home kitchen became a locus for change," noted John T. Edge (via NPR).

In addition to feeding the leaders of the Montgomery bus boycott, she also fed the participants. She would sell their wares — other women later did the same — and that network of freelance cooks coalesced into a committee that helped fund the boycott.

The Club From Nowhere

The boycott of the Montgomery, Alabama bus system brought with it its own set of challenges, not the least of which was the fact that the city's Black people, most of whom couldn't afford their own transportation, relied on it, as NPR reports. That meant that a network of drivers driving Black residents to their jobs and such would need to be formed, and that would take money: money for gas, money for insurance, money for repairs, and so on.

Georgia would take the proceeds from her food sales and put them towards funding the boycott. Other Black women soon joined, according to Southern Living, all of whom sold their pies, their boxed lunches, and their full Sunday meals to whoever was willing to pay. They would then pour that money back into the movement. As mentioned previously, due to the high stakes, secrecy was the order of the day. So when anyone asked about the provenance of the money, the respondent would just say, "it came from nowhere," giving rise to the club's name, the Club from Nowhere.

Georgia Died Doing What She Loved

Georgia Gilmore died on March 9, 1990, a date that coincided with the 25th anniversary of the march from Selma to Montgomery, per the Encyclopedia of Alabama. She died doing what she loved: cooking for the marchers, who were recreating the event. Specifically, she was cooking macaroni and cheese and chicken when she died, and in her honor, her family served the very same dish at her visitation. According to Mental Floss, a historical marker has stood outside of her home since 1995, placed there by the Alabama Historical Commission.

Having been a cook, it should come as no surprise that Gilmore's legacy also lives on via food. Specifically, her recipes live on in cookbooks. As the Montgomery Advertiser reports, Monica Tapper's book, "A Culinary Tour Through Alabama History," includes some of Gilmore's recipes, including a delicious pound cake, although Tapper is clear that her tome is not strictly a cookbook. "I love the fact that you and I can eat what they ate," Tapper said, referring to the figures from Alabama history whose recipes and creations are referenced in the book.