The American Physician Who Died Trying To Prove That Mosquitos Transmitted Yellow Fever

During the Spanish-American war, countless American soldiers lay shaking and sweating in their sick beds, taken down not by enemy bullets but by a deadly virus that still plagues the tropics today: yellow fever (via Johns Hopkins).

In the 21st century, this horrific illness is still a major problem across Africa and Latin America. Those who contract the virus exhibit flu-like symptoms along with the tell-tale yellowing of the skin and eyes. Unless the afflicted patient is very lucky, they will go on to experience internal bleeding and eventually organ failure. Yellow fever still kills between 20 to 50% of those who catch it, and for those who haven't been vaccinated, there is no known treatment available beyond waiting it out and praying for deliverance (via the CDC).

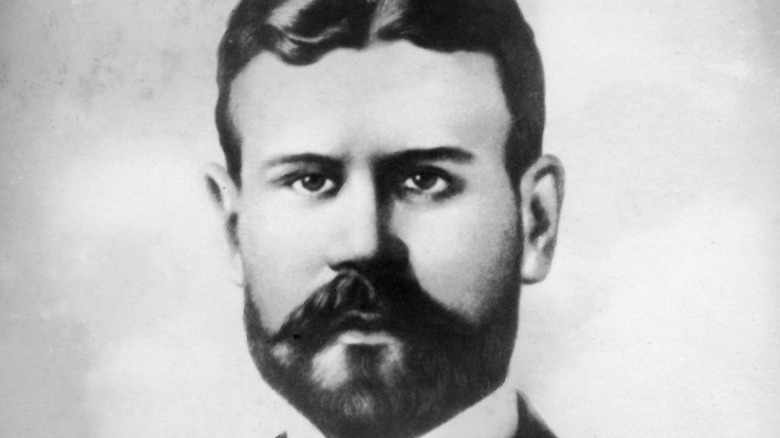

Once upon a time, the virus also plagued the U.S., with regular outbreaks shattering lives across the East Coast throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. An outbreak in Philadelphia alone killed 5,000 people in 1793 (via PBS). Unfortunately, at the turn of the 19th century, nobody understood how the virus was transmitted — which meant no safety precautions were taken to guard against the swarms of seemingly harmless mosquitos that brought legions of men to death's door. By the time the Spanish-American War hit, one whip-smart physician, Jesse Lazear, had become very interested in the illness. Lazear and his team began a series of mind-bogglingly brave experiments to solve the mystery — experiments that would save many lives but end Lazear's own.

Lazear's gambit

Jesse Lazear first became interested in the virus while working at the John Hopkins hospital in Baltimore, but he only began experimenting with mosquitos while working as an army surgeon in Cuba (via Johns Hopkins). Lazear was not some lone genius who studied the virus by himself — he was one of a group of scientists who all contributed to the discovery.

The medical consensus at the time pointed the finger of blame for yellow fever at unsanitary living conditions — dirty bed linen and clothing (via the University of Virginia). However, nobody had ever proven that bacteria was the cause of yellow fever, and a Cuban doctor — Carlos Finlay — had come up with an alternative hypothesis. Finlay argued that the humble mosquito was the true culprit, an idea that was regarded as a joke when his ground-breaking paper was first published in 1881 (via PBS).

By the time the Spanish-American War rolled around, yellow fever had once again become a terrifying menace — killing far more Americans than the war itself. The U.S. military soon intervened, creating the Yellow Fever Commission, a body that was tasked with solving the mystery of the virus' origins. Lazear was one of the doctors appointed by the commission (via NPR), and after a set of experiments ruled out the bacteria theory, it was Lazear who finally championed Finlay's work. It probably helped that Finlay's theory had been given renewed credibility by a British doctor, Sir Ronald Ross, who had recently proven that mosquitos could indeed spread disease in the form of malaria.

In the line of fire

The Yellow Fever Commission decided to conduct an experiment that today would have medical ethics boards tearing their hair out — they decided to use human test subjects to prove their hypothesis. The commission contacted Carlos Finlay and borrowed his mosquito eggs, taking them to a hospital in Havana for the experiment (via PBS). After exposing the mosquitos to a group of yellow fever patients, they in turn exposed a group of volunteers to the mosquitos (via the University of Virginia). The first of these experiments proved to be a failure because the virus had not been allowed to incubate for long enough in the infected bugs, throwing doubt onto the theory once again.

Perhaps because of these initial failures, Jesse Lazear's co-worker, doctor James Carroll, recklessly offered himself up as one of the volunteers, allowing himself to be bitten. This time it worked — Caroll got sick. The next volunteer, a soldier named William Dean, was also successfully infected shortly afterward, confirming that the experiment was on the right track. The news was such a big deal at the time that the head of the project, Major Walter Reed, wrote to his assistant, "Hip! Hip! Hurrah! God be praised for the news from Cuba today ... I shall simply go out and get boiling drunk!"

Lazear's death

Today, some people question how ethical these yellow fever experiments really were (via the AMA Journal of Ethics). However, the volunteers were most certainly not coerced — they were offered quite a lot of cash for their trouble, and some of them were so eager to help they refused the money (via the University of Virginia). Once the team started getting positive results, the Yellow Fever Commission stopped any self-experimentation, but tragically, despite the obvious dangers, Jesse Lazear decided to follow his colleagues' example and infected himself.

Although it was once believed to be an accident, an entry found in Lazear's journal confirms that he administered a bite to a mystery patient named "Guinea Pig No. 1" around the time he got sick. Unlike Carroll, Lazear did not pull through, dying on September 25, 1900. The gutsy doctor was not the only fatality from the experiments — in the third phase of the operation, three people died out of a group of 10 volunteers (per the AMA Journal of Ethics).

His legacy

The Yellow Fever Commission's findings were immediately put to good use. In Cuba, houses were fumigated and sealed off from bugs, measures that caused a rapid drop-off in yellow fever cases (via the University of Virginia). According to the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, the cleanup operation eradicated the virus from Havana in just eight months.

A few years later, in 1905, the commission's sanitation officer Major William Gorgas pushed Teddy Roosevelt to implement similar measures in Panama (via NPR). Yellow fever was a major problem for those working to build the Panama Canal — the virus killed thousands and regularly brought the project to a grinding halt. The commission's findings led to an anti-mosquito drive that put the breaks on the terrifying death toll.

After Panama, Major Walter Reed was praised to the skies for his role in the discovery, but Jesse Lazear's sacrifice was largely forgotten. His findings would go on to save many lives in the years to come, especially before a vaccine was developed in the 1940s. Today, yellow fever still kills thousands of people in areas where the vaccine is unavailable.