The Big Die-Up: How The Winter Of 1887 Changed The U.S. Forever

When you think of big, historic shifts in our culture and society, you tend to think of big-ticket events like wars, revolutions, and even elections. And while it's true that many of the changes that have shaped our country and our way of life have involved bullets and ballot boxes, Mother Nature often enters the chat to forever alter how we live.

While most storms — even enormously damaging and deadly storms — tend to be isolated moments in history that have subtle and slow-moving effects on society, there are exceptions. One of those exceptions is the blizzards that raked the Midwestern United States in the winter of 1887. An unusually powerful and persistent string of winter storms, these blizzards changed much about American life, shaping the country in ways we're still dealing with today.

And while most histories are concerned with battles and elections, some of the most consequential decisions made involve less exciting subjects. The winter of 1887 didn't change this country because of an invasion or assassination — it changed everything because of greedy, short-term thinking in the cattle industry. As the world enters a new era of dealing with the effects of extreme weather events that are increasingly impacting the way people live, it's worth studying the lessons from the Big Die-up and the winter of 1887 and how they changed the U.S. forever.

The 19th-century cattle bubble

If you've ever wondered where the term "cowboy" came from or wondered what a cattle drive was, both stem from the way the beef industry handled cattle back in the 1800s. As explained by Smithsonian Magazine, many people who migrated to the American West in the 19th century did so dreaming of making it big with beef. This was possible because most of the land in the area that is modern-day Wyoming, Montana, and the Dakotas was open, public land that was ideal for cattle grazing. This allowed people to have a monumental number of cattle without needing to pay much for their upkeep.

That's where the cowboys came in. According to History, cowboys in 19th-century America guided, protected, and managed these immense herds of cattle, driving them to market and branding them for their owners. While we tend to think of cowboys as a lifestyle marked by guns, horses, and campfires, it was a difficult job requiring specific skills.

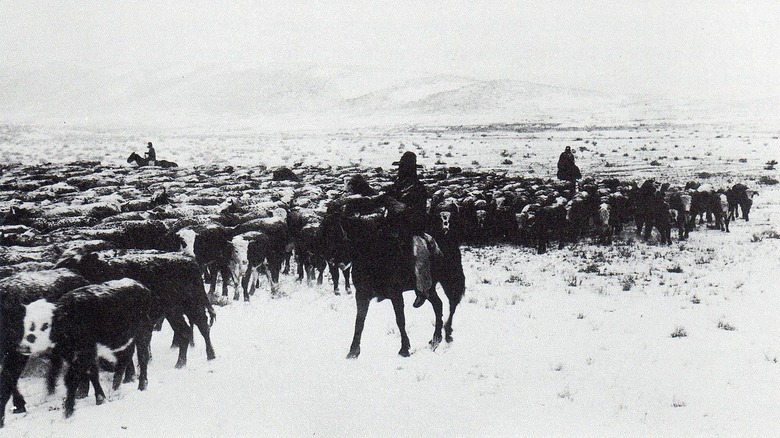

Cowboys were needed because of the "open range" policies of most cattle owners. As noted by the American Quarter Horse Association, the cows were simply allowed to roam the plains, grazing where they could. When it came time to sell them, the cowboys had to herd them up and drive them to their destination. The cattle were left out on the open plain even during winter.

Migrating cattle caused problems in the winter

Open-range grazing was cheap and made raising enormous herds of cattle cost-effective, but as noted by the Colorado Encyclopedia, it came at a high cost in terms of the environment. Huge herds of hungry cattle destroyed the plains, eating most of the plant life, compacting the soil into hard-packed dirt, and trampling and eroding everything in sight. Overgrazing made the plains less and less nourishing over time.

Despite the damage being done, there was a lot of money to be made. According to Britannica, foreign investors flooded the American beef market with capital, encouraging cattle ranchers to maintain the low costs of the open-range system. The U.S. government helped by passing laws making fencing largely illegal in the plains.

Additionally, according to the American Quarter Horse Association, the cattle tended to migrate south when the cold winters arrived, seeking warmer weather and better grazing. This meant that millions of cows wandered into the grazing areas of cattle ranchers in Texas and other southern states, destroying the grazing areas their own herds relied on. Since there was already an enormous number of cattle in those areas, the migrating cows from the north almost completely ruined the land for grazing.

Barbed wire and drift fences were introduced

With millions of cattle migrating south every winter, invading grazing land used by other ranchers, the affected cattle ranchers banded together to seek a solution. According to the American Quarter Horse Association, in the mid-1880s, ranchers seized upon the relatively new invention of barbed wire as a way forward. Barbed wire had been introduced in the 1870s, and the Panhandle Stock Association (PSA) decided in 1881 to construct an ambitious system of "drift fences" using the material.

The Texas State Historical Association explains that a drift fence is exactly what it sounds like: A fence designed to stop cattle from "drifting" past a certain point. Begun in 1882, the system of drift fences constructed by the PSA eventually stretched across the entire northern Texas Panhandle, covering close to 200 miles of the plains. Some individual pieces of the drift fences were more than 40 miles long. Once the fences were built, the rancher employed men to patrol them, keep them repaired, and stop anyone from damaging them.

Although the drift fences were not one continuous line — they were constructed piecemeal, with gaps running throughout — they proved to be very effective. And in many areas where no fencing was built, natural obstacles stopped the cattle from drifting south — rivers and other features of the land.

There was a warning in 1885

After cattle ranchers built hundreds of miles of "drift fences" to stop cattle from migrating south in the winter, Mother Nature issued a series of warnings of imminent disaster that went unheeded.

First, the Colorado Encyclopedia points out that cattle prices fell in 1885 because of the damage that overgrazing had done to the land. According to the American Quarter Horse Association, the winter that followed was a pretty bad one — colder than usual, and with more snow than the cattle ranchers had come to expect. When the weather finally warmed, ranchers discovered thousands of cattle had died "stacked up" against the drift fences — the cattle, starving and freezing, attempted to move south in search of food and warmer temperatures, only to be stopped by the drift fences, where they huddled together in desperation — and died.

Then, Smithsonian Magazine reports that the summer of 1886 was hot and dry, with a drought reducing the available water and further reducing the amount of forage that cattle could graze on. That meant that the cattle herds were already starving and in poor health by the time winter arrived. Despite all of these warning signs of a fragile herd headed for disaster, American Cowboy reports that very few of the ranchers had put in stores of hay to feed their cattle during the colder months, still trusting the open range system that had been seriously compromised by the drift fences.

The blizzards of 1886 were merciless

By the winter of 1886, the conditions for a disaster in the cattle industry were all in place. The grazing land had been ruined by overuse and a drought-plagued summer. Fencing had been built to prevent cattle from seeking warmer climates and food. And ranchers had made almost no preparations for the winter in terms of hay to feed their herds.

As noted by History, the winter of 1886 was historic. The American Quarter Horse Association notes that several enormous blizzards swept the Midwest — and according to American Cowboy, temperatures dropped to nearly 50 degrees below zero at times, while feet of snow driven by gale-force winds lashed the land. When the snow stopped, freezing rains followed, forming a layer of ice that prevented the starving cattle from accessing even the small amount of grass that was still there.

The cattle tried to move south in order to escape these lethal conditions but ran directly into the drift fences that had been constructed to stop them. These drift fences worked extremely well — they weren't very sturdy or well-built, but they stymied the cattle and trapped them, totally exposed, in the middle of some of the harshest winter weather the region had ever experienced.

The cattle died horribly

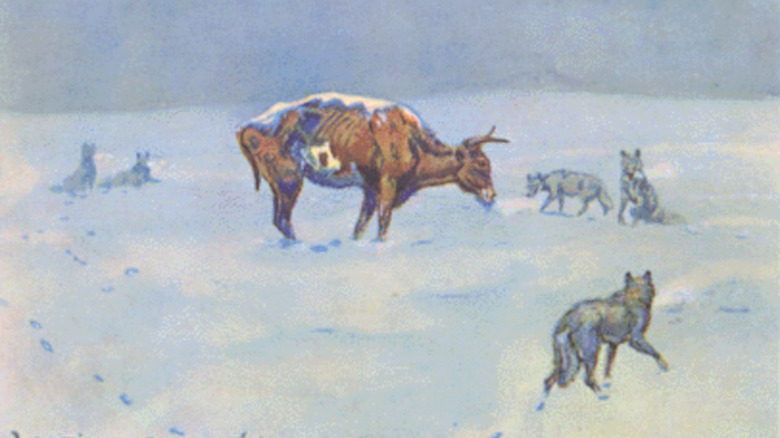

During the epic winter of 1886, cattle in the Panhandle region attempted to migrate south to escape but ran into drift fences that had been set up to prevent them. As noted by the American Quarter Horse Association, this had horrific consequences for the cattle. As temperatures dropped, the cattle began to "stack up" against the fences because they were unable to get past them. And they began to die.

By any definition, it was a massacre. Some of the cattle froze to death in the plummeting temperatures. Some were crushed and trampled by desperate cattle pushing in behind them. Some simply starved after a harsh summer and winter had already left them weak and fragile, while others drowned or were attacked by equally desperate wolves and coyotes.

According to the Texas State Historical Association, when the blizzards finally ended, cattle were found stacked up as far back as 400 yards from the fences, and piles of dead cows could be found along the fences for dozens of miles. Losses were almost unimaginable — some herds lost as much as 75% of their cattle, and by some estimates, as many as 400,000 cattle died during what became known as The Big Die-up.

Many ranchers went out of business as a result

The Big Die-up killed an incredible number of cattle, and some ranchers lost as much as 75% of their livestock in one horrific winter. But the industry was already suffering: As noted by author Randall K. Wilson in their book "America's Public Lands," the huge herds had flooded the market and driven prices down below a point that would have been sustainable. The cattle industry was already in severe financial distress.

At the same time, over-grazing and the combination of a dry, hot summer and a historically harsh winter had left the range denuded of grass and unable to support the animals that survived the Die-up. The result was an economic disaster for the beef industry. Smithsonian Magazine notes that many ranchers who had counted on the open range system to keep their herds alive went bankrupt and moved their operations back east. According to the Colorado Encyclopedia, there had been 58 large cattle companies operating in the American West in 1885. By 1888 there were just nine.

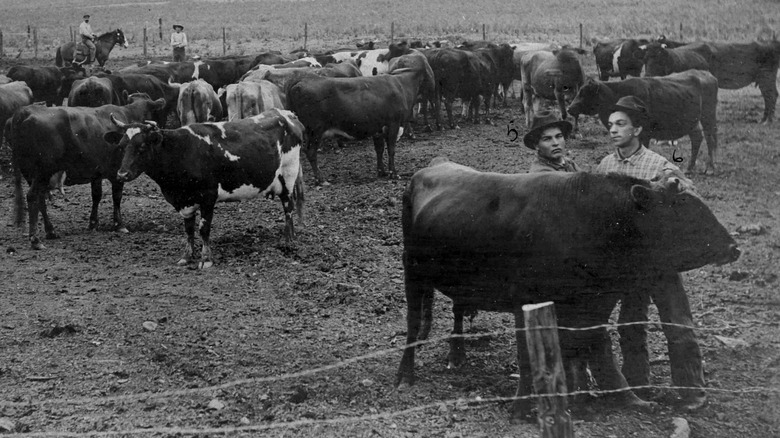

Not only were there fewer cattle ranchers, but the ones that did manage to keep operating did so on a much smaller scale, according to American Cowboy. The herds they managed became a fraction of the size of the gigantic crowds of animals that had once roamed the open plains, and their operations became very similar to farming, with stationary pastures instead of huge, mobile herds.

The Big Die-up made a president

One of the many ranchers who was devastated financially by the Big Die-up was a man with a very famous name: Theodore Roosevelt. In fact, if the Big Die-up hadn't occurred, he might never have gone on to become the 26th president of the United States.

According to the National Parks Service, Roosevelt invested $14,000 into a cattle herd with the brother of his hunting guide, Joe Ferris. This was a huge amount of money for Roosevelt at the time — more than he earned in a year — but Roosevelt not only saw a business opportunity, he imagined himself living out on the plains, roughing it in the West. As author Sarah Watts notes, Roosevelt's time as a cattle rancher became a big part of his "rough rider" persona. After his wife passed away in 1884, Roosevelt founded a second ranch and spent a great deal of time out West.

Roosevelt wasn't in the country when the winter of 1886 smashed into his cattle herds. As author Michael M. Miller notes in his book "XIT," however, Roosevelt lost nearly half his net worth in the Big Die-up — he described his losses as "crippling" — and the disaster prompted him to return to politics, running for Mayor of New York City that year. He was unsuccessful — but back on a path that eventually led him to the White House.

Legislation prohibited the fencing of public property in 1889

One of the big changes to the American West caused by the Big Die-up had to do with fencing on public lands. As noted by the American Quarter Horse Journal, one of the contributing factors to the Big Die-up was the drift fences that had been constructed on the open range that had trapped the herds of cattle during lethal blizzards. Prior to the disaster, most cattle ranchers simply marked their herds and let them forage for themselves, relying on these fences to keep them from migrating too far south and encroaching onto other herds' grazing land. This was despite the fact that these fences were already explicitly illegal due to legislation passed in 1885 prohibiting the fencing of public lands, according to historian Henry H. Perritt Jr.

Everything changed after the Big Die-up. After this ecological and environmental disaster that left hundreds of thousands of cattle dead and most cattle ranchers bankrupt, the legislation forbidding fencing of public lands was more regularly enforced, and individual states stepped in with their own laws. For example, authors Betty Dooley Awbrey and Claude Dooley note in the book "Why Stop?" that Texas passed a law in 1889 prohibiting fencing on public property, resulting in the removal of drift fences.

Cattle ranchers began using private fences

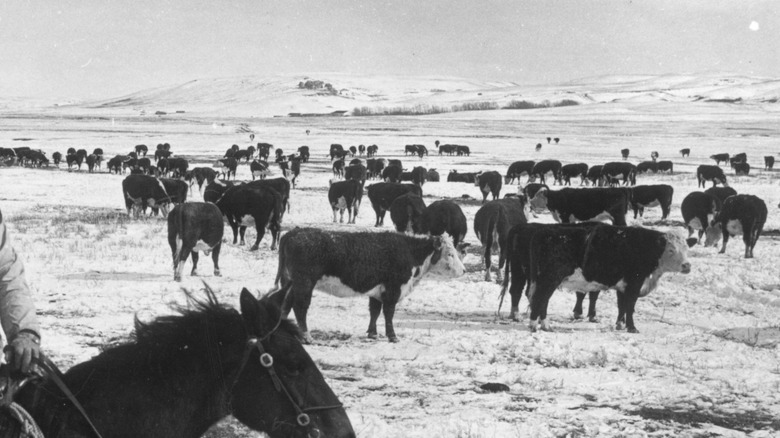

While illegal drift fences erected on public land were torn down and prohibited after the Big Die-up, which saw many cattle ranchers lose up to 75% of their herds and go out of business, the disaster actually increased fencing in the plains. If you've ever seen an old Western film depicting cowboys herding cattle across an open, natural landscape, you've seen something that basically stopped existing after 1886.

The American Quarter Horse Journal reports that the ranchers that were able to stay in business after the Big Die-up soon realized that they would never be able to operate using the open range system again. Not only were drift fences no longer permitted, but the enormous loss of cattle proved that the system left the herds too vulnerable.

The Colorado Encyclopedia notes that smaller cattle ranchers fared better during the Die-up because their herds were easier to control, track, and care for. In order to avoid going through something like the Big Die-up again, many of the practices of the smaller ranchers became the new standard as a result. Cattle ranchers began to purchase land and create fenced-in pastures — and since this was private property, the fencing was totally legal. This was the beginning of the ranch system we know today; as American Cowboy points out, this transformed ranching into a vocation similar to farming as these small-scale cattle ranchers had to grow food for their herds.

The U.S. Forest Service stepped in

The Big Die-up divides the cattle herds of the American West into two eras. The first, marked by open-range grazing and enormous herds of cattle left largely unsupervised, ended when the Big Die-up destroyed up to three-fourths of those herds. The second was marked by increasing regulation by the government.

As reported by the Colorado Encyclopedia, over the two decades following the Big Die-up, the federal government took an interest in preventing similar disasters. By the early 20th century, the U.S. Forest Service began a program of monitoring the ranges and enforced a permit system that worked to prevent overgrazing by tracking which herds were allowed to graze where. Not coincidentally, the U.S. Forest Service was created in 1901 by President Theodore Roosevelt, who had suffered enormous losses with his own cattle herds 15 years before.

As explained by The Rangelands Partnership, rangeland monitoring goes beyond tracking cattle and monitors the overall health of the ecosystem for signs of overgrazing, disease, and soil problems. This process helps to prevent the conditions — starving, fragile herds of cattle and denuded, overgrazed grasslands — that made the Great Die-up possible.

The era of the cowboy ended

Perhaps the most important consequence of the Great Die-up was the end of the romantic vision of the Wild West cowboy. As explained by American Cowboy, these jobs existed because of the open-range system cattle ranchers employed prior to the Great Die-up. With millions of cattle roaming freely on public land, cowboys were needed to keep track of them, herd them, and protect them. It was dangerous, hard work, but there was also a culture of open-door hospitality, wherein ranches often took in out-of-work cowboys for a time.

After the Great Die-up, everything changed. Ranchers no longer relied on the open range, penning smaller herds on dedicated, private pastures. And ranchers no longer relied on huge cattle drives administered by cowboys to get their herds to market — as noted by author Michael Wallis in his book "The Real Wild West," they began to rely on the newly-established railroads instead, putting cowboys out of work.

This did lead to a whole new trope of the Wild West, however, as many cowboys used the only skills they had to enter lives of crime, becoming cattle rustlers in an attempt to steal the herds they once safeguarded.