The Thanksgiving Disaster That Most People Haven't Heard About

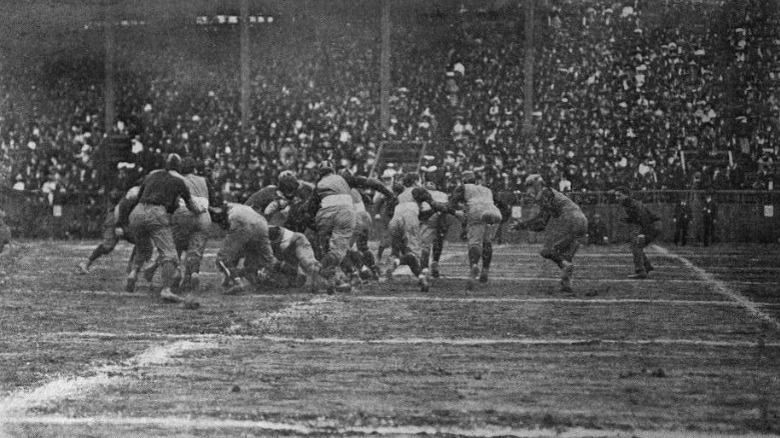

Thirteen years after President Abraham Lincoln proclaimed the last Thursday of November to be Thanksgiving (via History), the first college football game was played on Thanksgiving as part of the Intercollegiate Football Association championship in 1876, as per Bleacher Report. And within 20 years, football had become so intertwined with the holiday that Thanksgiving was called "the official holiday for watching football" by the New York Herald. As a result, it's no wonder that when Stanford University and the University of California, Berkeley, decided to start their football rivalry, they settled on a Thanksgiving Day game.

The Big Game that's played every year by Stanford and UC Berkeley has become known as one of the oldest sports rivalries in United States history, as per The Stanford Daily, and many fans can remember the detail of a game down to the minute.

But one game seems to have fallen out of the public consciousness; barely a trace of it can be found in the city of San Francisco. And few realize that one of the oldest rivalries in U.S. history is associated with one of the worst accidents in U.S. sporting history. This is the Thanksgiving disaster that most people haven't heard about.

The annual Big Game

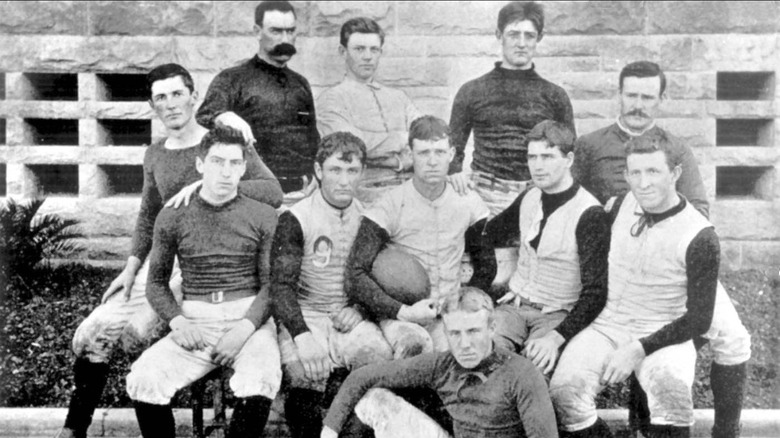

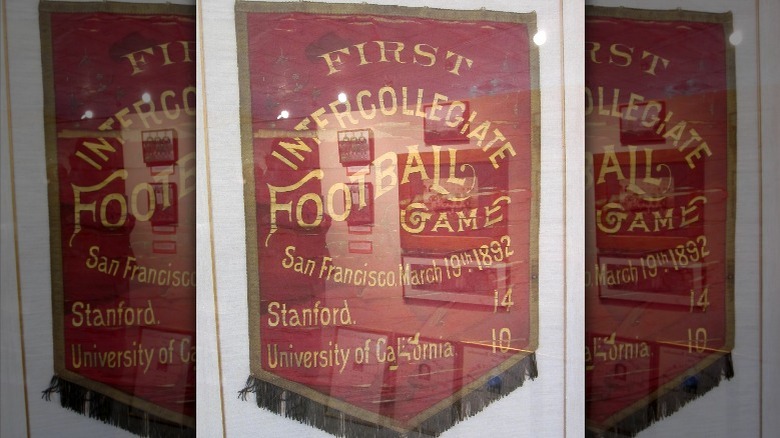

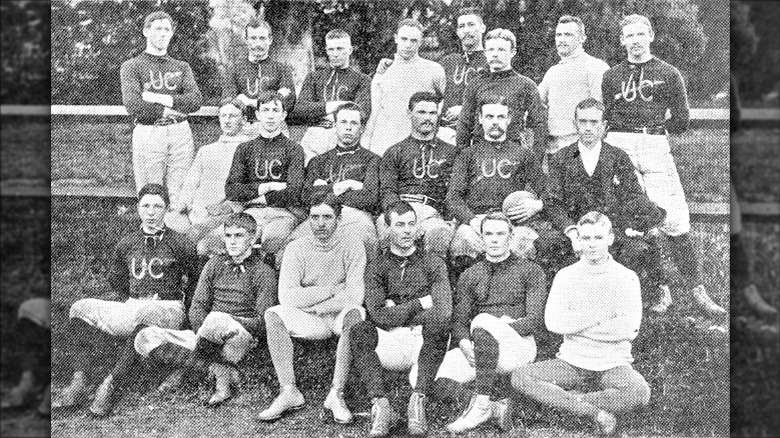

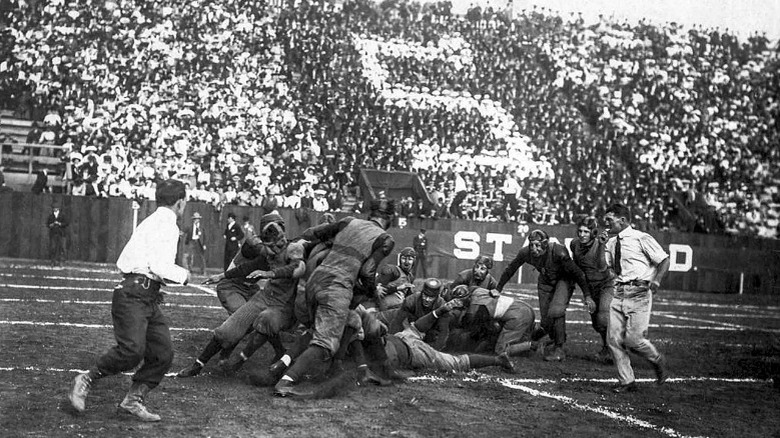

In 1892, the University of California, Berkeley, and the Stanford University football teams began a tradition that soon became known as The Big Game. While the University of California had been playing football since 1886, notes UC Davis Magazine, at the time, Stanford University's team was as new as the university. The tradition didn't start on Thanksgiving, however. UC Berkeley initially proposed a Thanksgiving match, but Stanford captain John Whittemore delayed the game till spring in order to give his team some time to practice. Stanford Magazine reports that he was the only football player on Stanford's team who had even played football before. He was quickly made captain, but the team didn't still didn't have a coach or a football to practice with when they first got together.

Nevertheless, Stanford won their first game against UC Berkeley 14-10 on March 19, 1892, effectively beginning one of the oldest sports rivalries in the United States, writes Stanford. The games were held annually, and traditions started developing around the sporting event, which was often played around Thanksgiving. And before long, it became the top sporting event in San Francisco of its time.

In "Herbert Hoover and Stanford University," George H. Nash writes that even future president Herbert Hoover was involved in the planning of the very first Big Game of 1892 as part of the team that rented the football fields, printed tickets, and collected cash admissions.

The collapse of 1897

Within five years, The Big Game had become so popular that grandstands were constructed to hold up to 10,000 spectators. But during the Thanksgiving Day game in 1897, even these stands weren't enough to hold the thousands of fans clamoring over one another to get a view of the already legendary rivalry. And as the crowds swelled, it became clear that disaster was right around the corner.

Stanford Magazine writes that during the 1897 Big Game, J.C. Weir, one of the contractors who'd worked on the stands for the game, watched in horror as over 15,000 people squeezed into the stands while dozens more had climbed onto the overhanging roof. Weir knew that the roofs were built only to keep off rain, and that the stands weren't strong enough to hold that many people, but no one listened to his warnings and, according to the San Francisco Chronicle, hundreds of boys continued to climb up and watch from the grandstand roofs. And during the final seconds of the game, the roofs finally broke under the weight, sending people crashing down.

Although many people ended up unconscious and bleeding with various injuries under the broken beams, remarkably, only one 10-year-old boy was hurt badly enough to warrant going to the hospital. One witness claimed that the fact that "many people were not killed or maimed for life is simply miraculous." But the warning of the disaster unfortunately went unheeded.

The SF and Pacific Glass Works factory

According to Bottles and Extras, during the turn of the 20th century, many American sporting games took place in industrial areas because large land plots were available and affordable. The constructed stands were also never made to last, and sporting events hopped around the town like a traveling circus. Many of the sporting arenas were often constructed very quickly in between the active factories and warehouses.

The 1900 Big Game was going to take place just across from the San Francisco and Pacific Glass Works. The Glass Works was just about to open for business on Monday, December 3, and in preparation, the east furnace had been burning for over a week to reach 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit.

The San Francisco Chronicle reports that as a result of the 1897 accident, those in charge of constructing the grandstand became wary of similar incidents. Knowing that the four-story factory rooftop would be prime seating — especially for those unable to get a ticket — the factory was ordered to make every accommodation to ensure the prevention of a potential accident before the game. To get Glass Works superintendent James Davis on board with taking measures to keep the roof clear of spectators, he was given six tickets to the game.

No ticket? No problem

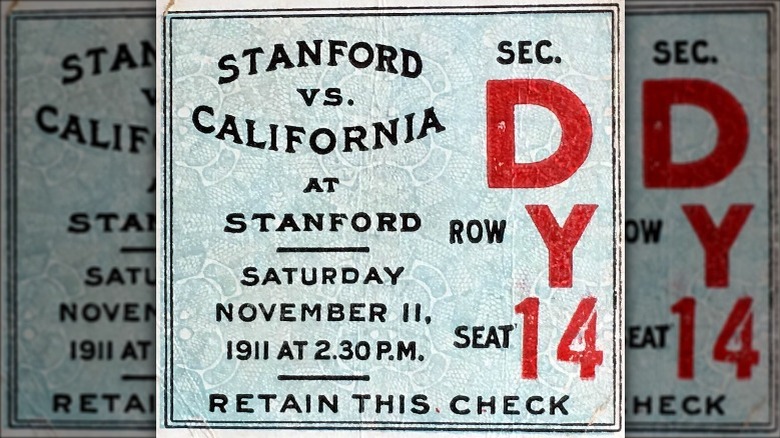

On Thanksgiving Day, November 29, 1900, the Stanford and UC Berkeley football teams got ready to meet on the field as fans started filling the stands around 10:30 in the morning. Thousands of people filed into the stands, but there were also numerous people who didn't or couldn't pay $1 for a ticket, equivalent to about $35 in 2022, who were scrambling to find a place from which to watch the Big Game.

Stanford Magazine reports that one student, 11-year-old Herman Guehring, tried to sneak in under a fence before being chased away and even tried climbing a water tower to be able to see the game. But, unable to get a good view, he climbed down from the water tower and joined the many people climbing their way onto the Glass Works building.

SFWeekly reports that people were able to get into the factory grounds by digging under the wooden fences and then opening the gates to all the arriving spectators. Factory management also claimed that some fences were broken down.

Densely packed with people

As SFWeekly details, by 2:30 p.m., the time of the scheduled kickoff, the Glass Works factory roof was densely covered with between 500 to 1,000 people. Although superintendent James Davis had been informed of the risk with the roof, the group of people soon got too large to control for even Davis and his workers to try to control. And there are conflicting reports as to whether or not the watchmen he hired took payment for allowing people onto the roof. Although factory workers were soon running through the streets looking for a police officer to assist them, they were unable to find anyone to help dispel the crowd on the roof, which was built to withstand only 40 pounds per square inch.

Spectator Herman Guehring later recounted that "it was like trying to turn back the waves at the beach. The kids kept pouring through the fence anxious to see the kickoff," per Stanford Magazine. But while trying to get a view, some of the crowd ended up standing on top of the ventilator directly above the 30-by-60 foot 3,000-degree-Fahrenheit furnace in the factory underneath.

Although some realized that it was a precarious situation, the throngs of people caged the unwilling victims in, preventing any sort of escape. One man recalled how "all of us were laughing and jesting and some of the fellows said if this thing breaks, we'll all go down together."

The roof collapses

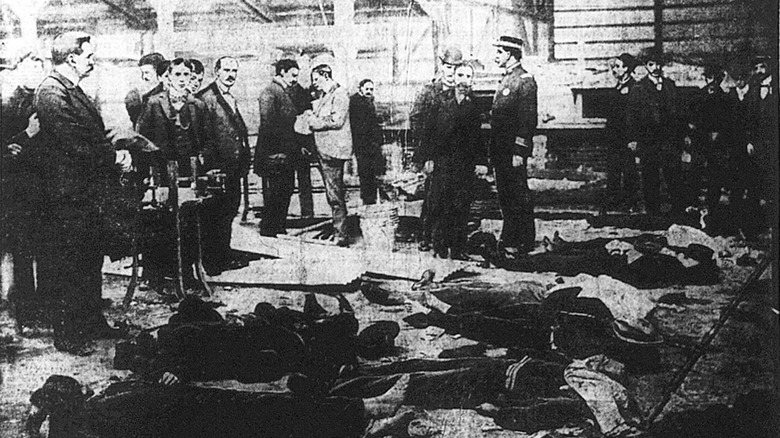

Within 20 minutes of gameplay, tragedy struck. The roof bearing up to 1,000 people collapsed and broke open into the factory, bringing scores of people down with it. SFWeekly reports that it happened very quickly, like the sudden opening of the gallows doors, one factory worker claimed. Although some people like Percy Fuller were able to grab onto something at the last second and hold on, many fell to their deaths. Fuller later recalled how he "turned to the building's interior and saw a writhing, yelling mass of humanity struggling to get out of a veritable hell."

Stanford Magazine writes that oven worker Charles Yotz, also written Jocz, was one of the first to realize what was happening as people started raining down on him while he raked the furnace fire. Some people landed on top of the furnace, which was about 500 degrees Fahrenheit. And while Yotz tried to push them off with a giant poker, another oven worker, Clarence Jeter, frantically turned off the oil feeding the furnace's fire. Jeter later stated, "It was a horrible experience standing there beside a hellpot and seeing human beings roast to death. We did the best we could."

It's estimated that over 100 people fell through the roof of the Glass Works Factory, and between 60 to 100 of them fell directly onto the furnace, as per SF Weekly. Many who fell were young men and boys, some of whom were as young as 9 years old.

Unimaginable agony

While some managed to hang on, those who fell onto the furnace ended up suffering some of the worst agony imaginable. SFWeekly reports that if the people falling from the roof had fallen directly into an open furnace, they would have died instantly. But instead, the falling spectators found themselves cooking alive on the 500°F furnace top as broken fuel pipes sprayed boiling oil onto them. Some were also unable to move independently due to their broken bones. While many who landed on the furnace were ultimately rescued, tragically, a 10-year-old boy who landed on the furnace was unable to be saved.

Yotz and Jeter managed to save dozens of people, although due to the frantic nature of the situation, they ended up tossing people off the furnace as quickly as they could, which meant paying little attention to the myriad of broken bones and wounds that people already bore. And for those out of arm's reach, metal poles were used to drag people off, sometimes even by hooking into people's flesh.

Stanford Magazine writes that when rescuers arrived, they were taken aback by the mass calamity. "The sight was awful. We knew not which way to turn or what to do."

The game must go on

When the roof of the Glass Works caved in, there was a tremendous crash that came from the football field's north side. Stanford Magazine writes that for a moment, gameplay stopped, and everyone briefly tried to discern what had caused the crash. One account claims that a UC Berkeley fan yelled, "It's a job," believing that the sound was a diversion from Stanford. But with little information as to what happened, they decided to continue to game.

Unfortunately, as the game resumed, "the bands and cheers overwhelm[ed] the screams next door." According to San Francisco Chronicle, some of the spectators had a sense that some bad accident had occurred, due to the fact that those sitting in the highest bleachers could see ambulances rushing to the scene. Meanwhile, police and attendants went through the stands while the game was ongoing, asking repeatedly if anyone in the crowd was a doctor. But despite this, the game carried on, and few were aware of the waking nightmare that was taking place next door.

When the game ended, with a Stanford victory, Stanford fans swept onto the field and paraded the star players down Market Street to the Palace Hotel.

A medical emergency

While part of the city of San Francisco was celebrating a Thanksgiving Day football victory, another part of the city was in the midst of a medical emergency. San Francisco Chronicle reports that dozens of people were taken to hospitals and thousands more followed them there, hoping for news of their loved ones. Because of the mass of people that started gathering at the Southern Pacific Hospital, police ended up barricading the doors to keep the crowd outside. The San Francisco Call reported that "Little boys in knee breeches were laid on the floor all along the length of the hall, some writhing with pains and calling for father and mother," per Stanford Magazine.

Meanwhile, bodies were delivered to the morgue on fragments of the destroyed roof as the supply of stretchers ran thin. And some of the bodies were so disfigured that their families were only able to identify them through their socks. Victims of the catastrophe were between the ages of nine and 46, but many of them were boys and young men. 13 people died the same day, but within four days, the death toll had risen to 22, with over 100 others being injured.

Many ended up with injuries that affected them for the rest of their lives. One of the final victims, Thomas Pedler, lived for three more years and endured spinal surgery, paralysis, and amputation before bringing the death toll to 23 in 1903.

A city in mourning

After the tragedy, the city of San Francisco was in a state of shock and mourning. One newspaper reportedly wrote that "Anyone returning from a trip instantly knew something bad had happened from the expression on people's faces," per Stanford Magazine. Over the following weekend, there were numerous funerals, with some even running back-to-back.

Newspapers like The New York Times quickly reported the tragedy, and the San Francisco Call called it "perhaps the most horrifying accident that ever happened in San Francisco." But at the same time, many who reported on the disaster wasted no time in switching to game coverage. The San Francisco Chronicle even described the game as the "closest and most exciting game of football ever played by the elevens of the two California universities."

And Mercury News reports that while other newspapers gave at least some coverage of the catastrophe, neither the student newspaper at Stanford nor the one at UC Berkeley gave any mention of the tragedy. A week later, the Stanford Daily did report that there was a rumor going around about a Christmas Day rematch that would raise money for families affected by the disaster, but even this was only a vague mention and such a fundraised was never held. Months later, the Stanford yearbook ever referred to their victory that day as "the most ecstatic moment of the year to the lover of athletics."

The worst forgotten disaster at a sporting event

Despite the fact that the Glass Works roof collapse during the 1900 Big Game became "the worst accident ever at a U.S. sporting event," and to date, this title has yet to be usurped, the accident seemed to immediately fade from the city's memory. A grand jury was convened, but according to Stanford Magazine, it bore the qualities of a show trial. And ultimately, the grand jury placed all of the blame on the people who had climbed onto the Glass Works roof to watch The Big Game. "[T]he deceased had no business being there. No one can be held responsible for their deaths other than themselves."

Mercury News writes that only a single physical memorial of the tragedy exists in the form of a small stone cross in Holy Cross Cemetery that marks the grave of a 12-year-old boy who died during the catastrophe. Neither the stadium nor the Glass Work factory remains, but "ironically, a UCSF facility now stands on the glassworks site."

And it's not only just the tragedy that was forgotten. Even the associated game is barely remarked upon in public memory. And while other 19th-century Big Games have commemorative statues, there's nothing dedicated to the 1900 Big Game. When researching the disaster for Stanford Magazine, Sam Scott found that even in local history books, there's barely a footnote to the 1900 tragedy.