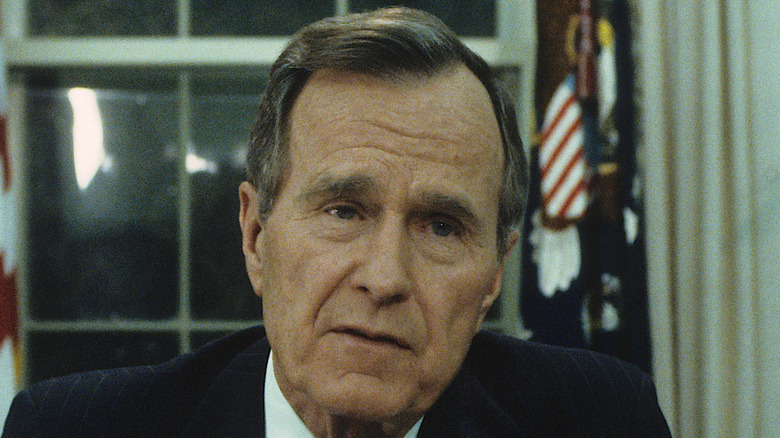

Questionable Things About George H.W. Bush's Presidency

George Herbert Walker Bush was the 41st president of the United States of America, serving from 1989 until 1993, per his official White House biography. He already led a life of distinction prior to becoming president, including as a World War II naval aviator, a member of the House of Representatives, director of the CIA for several years in the late 1970s, and vice president under Ronald Reagan.

At the time of his death at age 94 on November 30, 2018, Bush Sr. was eulogized by many as a sort of last of his kind. Per Town and Country, Alan Simpson, a former senator and close friend of the late president, said, "The most decent and honorable person I ever met was my friend, George Bush. One of nature's noblemen. His epitaph, perhaps just a single letter, the letter 'L' for loyalty. It coursed through his blood. Loyalty to his country, loyalty to his family, loyalty to his friends, loyalty to the institutions of government and always, always, always a friend to his friends.

But was he truly as steadfast and laudable as his friend's eulogy suggested, or was there much more to examine? Here are some questionable things about George H.W. Bush's presidency.

He tried to ban flag burning

The right to freedom of speech is enshrined in the U.S. Constitution thanks to the First Amendment. The clause about "abridging the freedom of speech," or rather not abridging it, has been widely interpreted to protect the many ways in which people wish to express themselves, be it in words spoken or written, in art, in song, or in acts that include the burning of the American flag.

But in late June 1989, not yet a half year into his presidency, George H. W. Bush proposed a constitutional amendment that would have, in a sense, trampled upon that very first amendment — he proposed an amendment to ban flag burning. Per the Los Angles Times, Bush said: "Support for the First Amendment need not extend to desecration of the American flag. Flag burning is wrong ... As President, I will uphold our precious right to dissent, but burning the flag goes too far and I want to see that matter remedied."

No such amendment was ever passed; had it been, it would have been a bitter irony, as Supreme Court Justice William J. Brennan Jr. argued at the time that the very symbol of American freedom would become less free itself.

He escalated the War on Drugs

The term "War on Drugs" was first used in 1971 by President Richard Nixon, per the Drug Policy Alliance. Nixon enlarged and empowered myriad federal agencies that engaged in the effort to curtail the spread, sale, and consumption of illicit narcotics in the U.S., but drugs nonetheless found their way into and around the country in ever larger numbers. Then came the surge of use of crack cocaine in the 1980s that led many people to call out a "Crack Epidemic," per Britannica. President Ronald Reagan would, like Nixon in the decade before him, devote significant resources to the fight against illegal drugs, but for George Bush Sr., the war on drugs became something of a messianic affair.

In a televised address — his first in office — given in early September 1989, Bush said that drugs were "the greatest domestic threat facing our nation today" (via C-SPAN). In ramping up the battle against drugs even more dramatically than had his predecessors in the Oval Office, one step Bush took was to have many state and local police forces armed with military grade weapons and equipment, as per Vox, including assault rifles and armored vehicles, and to call for ever stricter sentences for those convicted on drug charges, notes The Washington Post. These approaches demonstrated a harsh, hard line stance that now, a generation and some later, is essentially the exact wrong way to deal with the problem; treatment programs work far better, per Turning Point of Tampa.

George H.W. Bush ordered the illegal invasion of Panama

America's history with Panama is long and twisted, going right back to the formation of the nation and the immediately subsequent construction of the Panama Canal, both of which happened under the thumb of President Teddy Roosevelt, as per the State Department's Office of the Historian. The often dark shared history of the nations only worsened in the 1970s when, per History, the CIA recruited a man who was rising through the ranks of the Panamanian military named Manuel Noriega. For nearly the next two decades, Noriega would be in and out of favor — and on and off the shadowy payroll of the American government — as the U.S. sought to use him as part of its check on communist expansion in the western hemisphere. Noriega remained a partner of the U.S. despite the fact that by the late 1970s he was a known drug trafficker and, by the mid-1980s, he was a corrupt strongman dictator of Panama.

It was not until 1988 that America finally disavowed Noriega fully, it having come to light that he had acted as a double-agent for communist elements in Panama and Cuba. The next year, in December 1989, amidst growing U.S.-Panama tensions and following the death of an off-duty American Marine in Panama, George H. W. Bush ordered thousands of U.S. troops into Panama in what was titled "Operation Just Cause." While there was congressional bipartisan support for the invasion, notes Politico, others decried the illegality of the operation, claiming that it violated international law, as per the Columbia Journal of Transnational Law.

He went back on his biggest campaign pledge

The signature line from the presidential campaign of George Herbert Walker Bush was this: "Read my lips: no new taxes" (via NBC). It was music to the ears of fiscal conservatives all across America, and Bush's stated plan to oppose all tax increases or new taxes helped him win the presidency in November of 1988. But it was a pledge the president would not be able to keep. On November 5, 1990, per record from Congress, Bush signed into law H.R.5835, aka the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990, which had been introduced into the House of Representatives by the democrat Leon Panetta (later the Secretary of Defense) less than a month earlier.

While many on the right felt that Bush had betrayed them and broken an ironclad promise — and indeed he did go back on a pledge — his willingness to sign that bill into law was seen by many as an act of courage, per the Cato Institute, as it was a necessary move to stem the slide of the American economy. The bill raised the top tax rate on wealthy Americans from 28% to 31% and reduced the number of possible tax deductions — and indeed it did help the U.S. grow revenues in coming years — but ironically, with recession already in the offing in the fall of 1990, in the years immediately following passage of H.R.5835, the revenues of the American government actually fell as compared to the years immediately prior.

The 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act has been the cause of litigation

On its face, the Americans with Disabilities Act, commonly referred to as the ADA, that President George H.W. Bush signed into law in 1990 would seem to be nothing but a good thing. After all, it was intended to protect the rights and the wellbeing of Americans with physical and mental impairments, as per the ADA — in short, the ADA was intended to make sure that even people with different abilities and limitations than the average American were still afforded a full and protected place in the nation's civil society.

In practice, however, the ADA was written in such a way that is open to interpretation. As The Regulatory Review notes, questions abound regarding who is actually covered under law and what its requirements are. As good as its intentions are in spirit, and the bill has served to benefit a litigious society, with myriad court cases — including going all the way to the Supreme Court — since it was enacted.

Likewise, enforcement of the law has been spotty at best, even in cases where such would have provided a clear benefit, as demonstrated by a judge ruling New York City had failed to install audible signals at city crosswalks that would keep vision-impaired people safe — the ruling was handed down in 2020, 30 years after the ADA was passed.

His ambassador to Iraq OK'd Saddam Hussein's invasion of Kuwait

The military action in the Middle East known as Operation Desert Storm was anything but the cut and dried and justified war that it is seen by many to have been. Indeed, the First Gulf War started with America operating under false pretenses and was conducted in a manner beyond unbecoming of the mighty American military and its martial and civilian commanders. Exhibit A, as it were, is the fact that the Bush Administration would act as though they were entirely surprised when the Iraqi military, led by dictator Saddam Hussein, invaded neighboring Kuwait in the summer of 1990. According to his 1990 address to the nation (via UC Santa Barbara), President George H.W. Bush said in public that the invasion had been "without provocation or warning." But that was not true.

What Bush did not say was that, acting in an official but very much below the radar capacity, the American ambassador in Iraq at the time, April Glaspie, had, just a handful of days before Hussein's invasion, said to the Iraqi dictator: "[W]e have no opinion on the Arab-Arab conflicts, like your border disagreement with Kuwait." As Foreign Policy argues, this could be viewed as a green light for Iraq to invade its diminutive neighbor.

The U.S.-led coalition attacking Iraq in 1991 targeted civilian infrastructure

Though Saddam Hussein had the fourth largest army in the world at the time of his 1990 invasion of Kuwait, with nearly 1 million soldiers (via the Federation of American Scientists), Iraqi forces would rapidly crumble in defeat as the American-led coalition swept in. But per reporting from The Washington Post published about a year after the outbreak of hostilities, the Iraqi military was hardly the only thing the coalition forces attacked. In fact, often the primary targets of American and allied bombs, rockets, missiles, and artillery were proven to have been Iraq's civilian infrastructure, much of which was totally destroyed during a withering 43-day bombardment.

The destruction of everything from power stations to sewage treatment plants crippled everyday civic life in Iraq, clearly part of a larger strategy deliberately implemented by American and allied forces — it was the latter day equivalent of surrounding a castle, burning grain fields, and catapulting animal carcasses over the walls. Though the damage that was wrought upon civilian infrastructure was almost always called "collateral" and referred to as accidental or incidental to the primary military objectives, it later became clear that was simply not the case.

Sanctions in Iraq following the Gulf War were ruinous for Iraqi civilians

Following the utter defeat of Saddam Hussein and the Iraqi forces in the First Gulf War, America and its allies could have taken an approach much like they did with erstwhile enemies a half century before, when the allies helped rebuild Germany and Japan following the horrors of World War II. Instead, the victors took a very different approach. Iraq would be slapped with such punishing sanctions that any sort of true and meaningful recovery — one that might have helped foster an improvement of governance along with betterment of the lives of ordinary civilians — was impossible.

Imposed at the start of the war and left in place after it, per the Middle East Research and Information Project, Iraq was cut off from all global trade; imports to and exports from Iraq were completely curtailed with precious few exceptions allowed for some medicines to enter the nation. Even shipments of food were largely prohibited except when clear evidence of looming famine presented itself. And in various forms, harsh sanctions would remain in place throughout the rest of the Bush years and well on into the Clinton presidency.

George H.W. Bush did little to stem a recession

For a while in the early 1990s, George H. W. Bush enjoyed very high approval ratings in the wake of American victory in the Middle East. That popularity was not to last, though. And as tends to happen to so many presidents, the reason his popularity plummeted was an American economy in decline. According to The Seattle Times, in 1992, an election year, America entered a recession, and, offering little meaningful solutions to the economic downturn, Bush would pay for it when he lost his reelection bid to Bill Clinton that November.

Though the recession of 1992 was short in the scheme of things, it was painful for many, with unemployment hitting 7.8%. What's more, that recession was seen in the eyes of many voters as just the latest economic debacle for which Bush Sr. was afforded the blame, what with the Savings and Loan Crisis that had lasted throughout the entire 1980s, per Federal Reserve History. Those years saw a stunning number of financial institutions close down and saw inflation and interest rates both surge.

He sent 28,000 troops into the Somali civil war

In the closing weeks of his presidency, while already in "lame duck" mode, having lost his bid for reelection, George Bush Sr. ordered a major American military operation that would prove to be an outright debacle. In December 1992, Bush ordered 28,000 American soldiers into Somalia, calling their mission "God's work" (in his own words) and naming it "Operation Restore Hope," per History. Bush said the soldiers would help save more than a million Somalis from famine caused by the blocking of humanitarian aid by warring groups in the area. The president pledged that the American intervention would be brief and efficient and that troops "will not stay one day longer than is absolutely necessary." But, of course, that's not at all what happened.

Americans forces became deeply embroiled in the conflicts between rival warlords and soon found themselves a part of a problem with no clear solution. The American experience there — inspiration for the book and film "Black Hawk Down" — would drag on for well over a year, with troops remaining in Somalia until they were finally summarily withdrawn by President Bill Clinton in late March 1994. Despite what Bush had said at the outset, the American intervention in Somalia did almost nothing to change the frightful realities on the ground. Though to be fair, neither did the efforts of some 20,000 United Nations troops who stayed on before giving up on the region and leaving.

He pardoned several members of the Iran-Contra scandal shortly before leaving office

It is the right of the president of the United States of America to pardon a person convicted of a federal crime. And it has been the practice of many American presidents to do so right at the end of his term in office. Such was very much the case with George Bush Sr. On Christmas Eve of 1992, less than a month before he would vacate the White House, Bush pardoned multiple men who had been wrapped up in the Iran-Contra scandal, including one of its major players, the former Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger, per Politico. Per Gov Info, he opened his executive order, writing, "Today I am exercising my power under the Constitution to pardon former Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger and others for their conduct related to the Iran-Contra affair."

Per the Los Angeles Times, incoming president-elect Bill Clinton said at the time the pardons indicated that many government officials could act as if they were "above the law." Of course, the power of the presidential pen can be quite a draw — Clinton himself would issue hundreds of pardons, per the Department of Justice, and some were controversial in their own right.