The Tragic Story Of Big Star

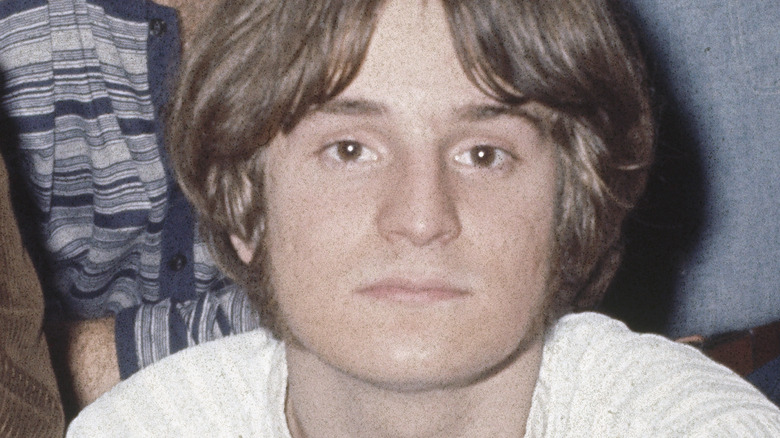

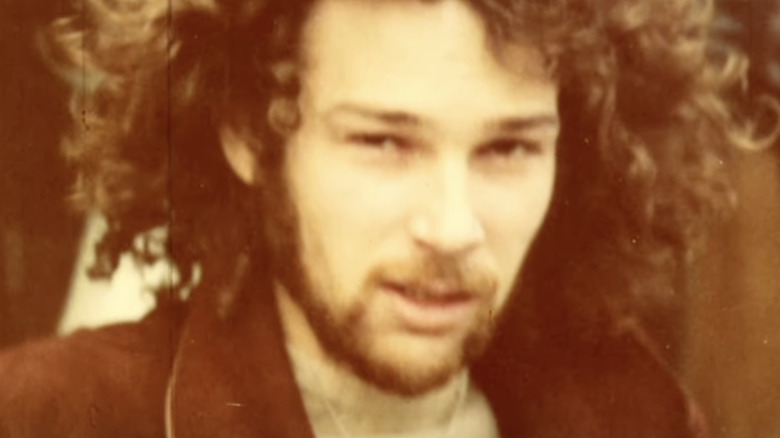

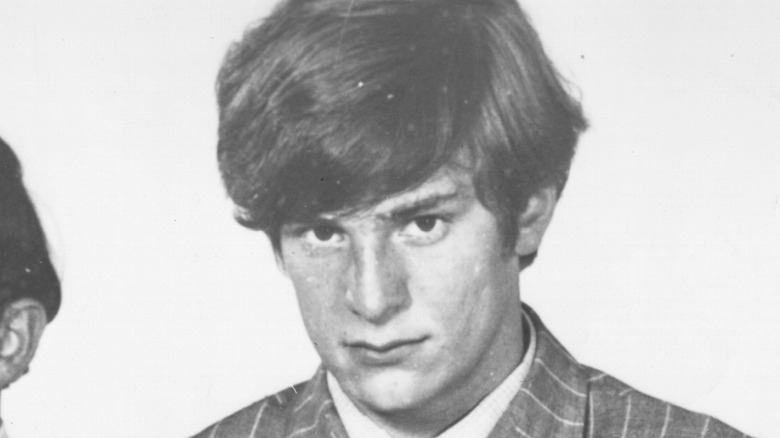

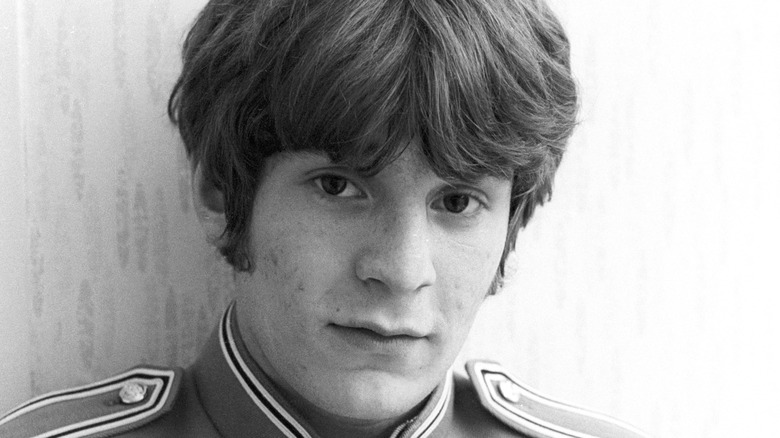

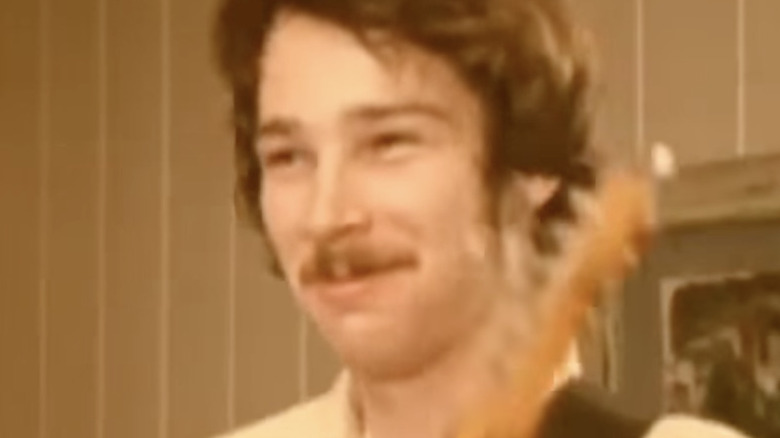

Big Star never had a No.1 record – unless you count their debut album, which they titled "#1 Record" — and they only produced three albums in their original incarnation, but they're one of the most acclaimed and adored bands in rock history. Formed in the early 1970s in Memphis by former teen idol Alex Chilton and difficult-to-categorize singer-songwriter Chris Bell (with Jody Stephens and Andy Hummel comprising its most lasting lineup), Big Star is credited with the creation of "power pop" (via Manet), combining shimmering and jangly guitars with hard-rock crunch and endless catchy hooks. None of their music ever sold well, but it inspired the next generation of bands — R.E.M., the Bangles, and the Replacements are among the many bands who cite Big Star as a formative influence, while they're probably best known for the original version of "In the Street," later used as the theme song to "That '70s Show."

In part because of the tragedy, loss, and what-might-have-been that surrounds Big Star and its members, the band has become legendary, responsible for a small but complex, alternately joyful, haunting, and resonant songs from the past that the world just wasn't ready to hear. Here's a look into the sad saga of Big Star.

Both of Alex Chilton's brothers died young

Alex Chilton was largely raised in Memphis, and he had three siblings, including a brother named Reid, 11 years his senior. One day in 1954, when Alex was three years old and Reid was 14, the elder Chilton brother climbed a tree in the backyard of the family's home, only to slip during the activity and fall quickly and hard onto the ground below. Reid Chilton didn't break any bones, but he was immediately rendered unconscious and, while hospitalized, lay in a coma for three days.

"My recollection is that the doctor told my parents that anytime anyone is unconscious for that length of time, there's some brain damage that might show up at some future point," sister Cecelia Chilton said in "A Man Called Destruction." But when Reid awoke, he seemed fine, neurologically speaking. Reid Chilton wasn't fine. He would go on to suffer seizures, and in 1957, when he was 17 years old, Reid had a seizure while taking a bath, and he drowned. The children's mother, and 6-year-old Alex, discovered the body.

Another brother, Howard Chilton, lived next door to Alex Chilton when the latter lived in New Orleans in the 1980s and 1990s. After grappling with some long-term health issues, Howard suffered a heart attack at home in June 1992 and died at the age of 46.

The release of #1 Record was so botched that Big Star fell apart

Big Star's first LP, "#1 Record," was released in August 1972 and rock critics wildly praised it then and forever, with it landing in Rolling Stone's list of the best albums ever made. However, even if the general public wanted to hear the album upon its initial release, it was very difficult to do so. Big Star's label, Ardent Records, was a newly formed subsidiary of Stax Records, an influential, Memphis-based producer and distributor of soul and R&B music. According to Vice, executives at Stax didn't know how to market a rock record, lacking the channels and correct (or enough) personnel to do so, and it utilized an arcane and outdated album distribution system. Besides, in 1972, the company's attentions were directed at marketing Isaac Hayes' hit "Hot Buttered Soul." In essence, Stax and Ardent couldn't get "#1 Record" into very many stores, and sales suffered, registering it as a commercial flop.

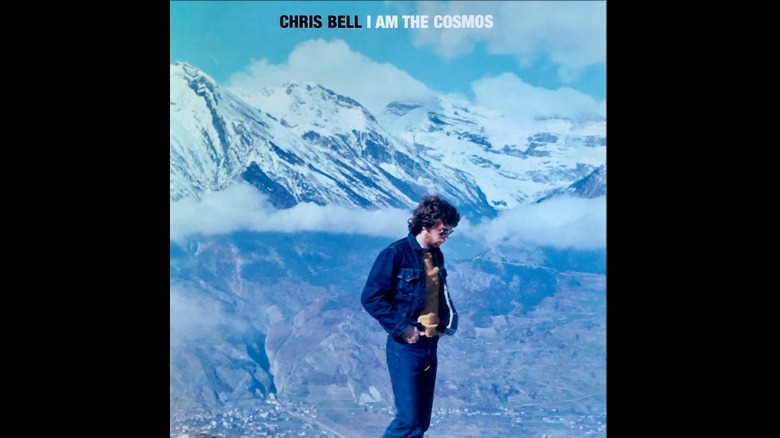

By the end of 1972, according to "There Was a Light," Big Star co-leader Chris Bell was so upset over the failure, and reportedly feeling overshadowed by Alex Chilton, according to The Guardian, that he quit the band. Following the recording of Big Star's second album, 1974's "Radio City," bassist Andy Hummel, tired of the creative squabbles and commercial indifference, according to Spin, also quit the band, and music entirely, and went to college.

Chris Bell repeatedly attempted suicide

According to "There Was a Light," Chris Bell left Big Star following the failed rollout and dismal commercial prospects of the group's debut album, "#1 Record." He was also suffering from mental health issues. "Somehow, Chris got it into his head that we and all these people were against him," Alex Chilton said. He was also reportedly miffed when after announcing his departure from Big Star, nobody in the band tried to stop him from leaving. Only bassist Andy Hummel regularly spoke with Bell at this time. "I did communicate with Chris," Hummel said, "but it was all very negative, Like, 'Andy, do you have a gun? I need to borrow it.'" Bell would later admit that he had grown depressed because he'd put so much creative effort into Big Star, and it had failed, and he feared he'd never have another similar opportunity.

In late 1972, after going to Ardent Studios and attempting to erase part of the "#1 Record" masters, Bell drove to his parents' home in Germantown, Tennessee, and attempted suicide. Fortunately, a relative took him to a hospital, where his stomach was pumped and he was placed under psychiatric care. After his release, and sometime later, according to Memphis musician Tommy Hoehn in "There Was a Light," Bell attempted suicide once more, but he survived.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Chris Bell struggled with his sexual identity

During the holiday season of 1978, according to "There Was a Light," Chris Bell developed a case of seasonal depression on top of his other issues with mental health and addiction, and he looked to religion as a solution to his problems. One of his issues, according to friends, was that he was struggling to come to terms with the knowledge that he was gay, and balancing that with his newfound commitment to Christianity, which in the Southern United States in the 1970s, took a point of view that was far less than broad acceptance.

"Chris never came out as a homosexual," friend and musician Tommy Hoehn said. "I always knew that Chris at least leaned that way. One thing that tormented him was that he'd become a Christian and that his orientation had not necessarily changed." While Bell reportedly had same-sex relationships earlier in his life, he wasn't known to have become romantically involved with another man after his conversion to Christianity.

Alex Chilton attempted suicide

On two separate occasions a decade apart, low periods in his professional life led Alex Chilton to attempt to take his own life. According to "A Man Called Destruction," 16-year-old Chilton believed in his high school garage band, The Devilles, but members kept quitting, despite having recorded a promising soul-rock single called "The Letter." Then his girlfriend broke up with him, in favor of hanging out with older, local criminals. He started drinking more, and then he tried to end his life. Chilton instantly regretted the decision and panicked, and his father took him to a hospital where he was treated and released; months later, "The Letter," credited to The Box Tops, with Chilton on lead vocals, hit No.1 on the Billboard pop chart.

One night In 1976, after the recording of what would become the third Big Star album, Chilton spent a night drinking and taking large amounts of prescription pills, and went to his parents' home, where he re-created his earlier suicide attempt. Chilton's father once again took him to a hospital, where the musician was bandaged and placed under psychiatric observation. Swearing off drugs, Chilton checked himself out of the facility and went back to his parents' home to recover.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Big Star's label rejected, delayed, and mismanaged a record the band didn't even like

Big Star's remaining members, Alex Chilton and Jody Stephens returned to Memphis's Ardent Studios late in 1974 to record a supposed Chilton solo project, per "33 1/3: Big Star's 'Radio City.'" According to American Songwriter, label executives decided to release it as a Big Star album — and then they opted not to release it all once they heard the finished product, according to The Guardian, a freewheeling and experimental project. (Per AllMusic, parent company Stax was preoccupied with bankruptcy in the offing.) Ardent head John Fry mastered the album, printed up a few hundred test copies, and Chilton and Stephens, who weren't entirely confident in the music, tried to shop it around to other labels, garnering no interest.

More than three years later, indie label PVC Records acquired the master tapes and put together an album it placed in American and English stores under the name "Third." Over the years, multiple reissues would surface, with slightly differing songs and sequences. Finally, after seven years of inconsistency, PVC reissued the album, per "A Man Called Destruction," in 1985 as "Third/Sister Lovers," the latter part coming from a jokey band name the duo gave themselves in the '70s when they were dating Memphis sisters Lesa and Holliday Aldridge.

At any rate, Chilton was so shaken up from the whole experience he later disowned the album, which would be the final Big Star-branded work, not counting occasional brief reunions in the '90s.

Alex Chilton's first marriage ended in divorce and death

According to "A Man Called Destruction," The Box Tops played the Fort Worth Teen Fair multi-act rock festival in 1967, and while partying at a Holiday Inn, Chilton met Suzy Greene, a 20-year-old who lived on a hippie commune. At the end of 1968, on Chilton's 18th birthday, they'd get married by a justice of the peace in Memphis, nine days after Greene gave birth to the couple's child, Timothee.

The marriage suffered under the weight of Chilton being on the road and the burdens of new, young parenthood, which wasn't the first time Chilton had been pegged as the father of a child born to a woman he barely knew; his parents even unsuccessfully persuaded him to get a paternity test. By early 1970, Chilton had started seeing a Memphis State student named Vera Ellis. He'd move to New York with her, dumping and divorcing Greene.

In the late 1980s, Suzi Greene died by suicide, according to Memphis Magazine. Her son with Chilton, Timothee Chilton, was sentenced to a 12-year prison term in Oklahoma in 2009 for assault and battery with intent to kill.

Chris Bell died in a single-car accident

On the day after Christmas in 1978, Chris Bell attended church surfaces, where according to "There Was a Light," he was confronted by a parishioner for sporting long hair and a beard. Then he went to a musical rehearsal and jam session at the home of the leader of The Tommy Hoehn Band. As the playing and songwriting lasted into the night, the musicians drank, and according to "A Man Called Destruction," Bell became intoxicated on Mandrax, a Mexico-produced version of the powerful narcotic quaaludes.

At about 1 a.m., on what was by then December 27, per "There Was a Light," a friend dropped off Bell at his vehicle, a small Triumph sports car, so the guitarist could drive himself home. He never arrived; at 1:25 a.m., Bell traveled through an intersection and the car grazed a curb. That caused Bell to lose control of it, cross through a residential driveway, and strike a wooden utility pole at a speed of about 40 miles per hour. Bell's Triumph then careened back into the street, causing the pole to dislodge from the ground and fall onto the vehicle. Bell died instantly, only a few yards from the Knickerbocker, the restaurant his father operated.

According to the Memphis Commercial Appeal, Bell was just 27 years old. The funeral took place on December 28 — Alex Chilton's birthday, but he was unable to attend the service.

Alex Chilton nearly died in Hurricane Katrina

In 1982, according to Antigravity, Alex Chilton moved to New Orleans, seeking a fresh start in life in a place where he didn't really know anybody. He took a string of low-paying jobs, per The Ringer, including trimming trees, sweeping bar floors, and washing dishes, and not writing or performing any music for a decade.

He eventually saved up enough money to buy a cottage he called The Hideaway in the Tremé neighborhood of New Orleans — but it was destroyed when Hurricane Katrina pummeled the city in the summer of 2005. As the floodwaters rose, Chilton refused to leave his home, afraid looters would break in, per BrooklynVegan, so he boarded up the widows and thought he'd just wait out the storm. Friends around the U.S. didn't hear from Chilton for five days, and they feared he'd died, but when the situation became unbearable and he ran out of food, he made his way to his roof and waved his arms until he got the attention of an evacuation helicopter, which airlifted him to safety, according to Billboard. The home suffered extensive, expensive damage, according to NOLA.

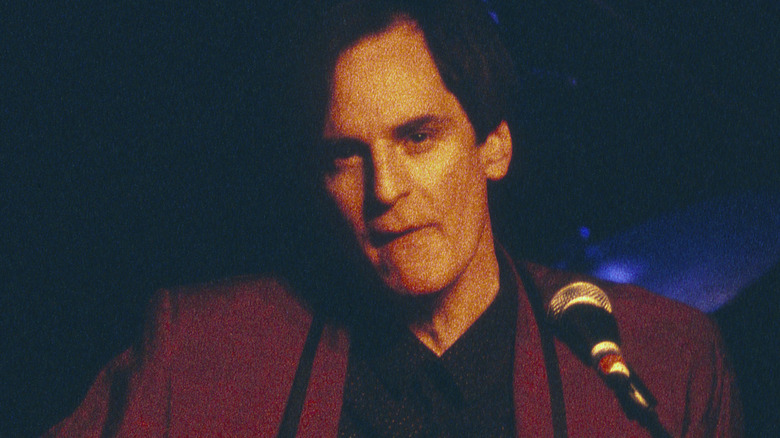

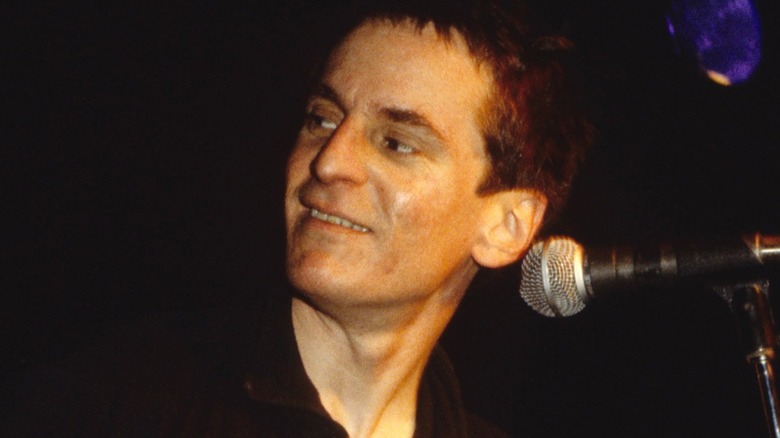

Alex Chilton died of a heart attack

In March 2010, while living in New Orleans with Laura Kersting, his wife of seven months, Alex Chilton noticed and mentioned that he suffered shortness of breath and chills while cutting the grass outside his home on two separate occasions, according to NOLA. Despite those troubling and potentially serious symptoms, Chilton didn't visit a doctor or head to an emergency room, Kersting said, in large part because he didn't have the health insurance that would've made such a trip routine and affordable.

Days after his last episode, on the morning of March 17, Chilton called Kersting at work, noting the same breathing troubles and chills. While Kersting drove Chilton to a hospital's emergency room, he lost consciousness and never regained it. According to the Los Angeles Times, Chilton made it into a New Orleans emergency room where doctors pronounced him dead of what was suspected to be a heart attack. Chilton was 59 years old.

Andy Hummel died after cancer treatments

Alex Chilton died in March 2010, a few days before a scheduled celebration of his life and work at the SXSW Music Festival in Austin, Texas, according to Pitchfork, headlined by a first-time-ever reunion concert performed by a reconstituted Big Star, featuring Chilton, original drummer Jody Stephens, and original bassist Andy Hummel. In the wake of Chilton's death, the reunion didn't happen, and the event became a posthumous tribute show, according to Spin, with members of R.E.M., the Cowsills, and the Lemonheads performing, along with an appearance by another surviving member of Big Star, bassist Andy Hummel.

That Big Star love-fest would wind up bittersweet, as it was ultimately one of the final public appearances of Hummel. In July 2010, just four months after Chilton died of a heart attack, according to Rolling Stone, Hummel died. He'd quit playing music professionally in 1974 after leaving Big Star, occasionally performing small gigs with friends around Weatherford, Texas, where he'd lived for years after taking a job at aircraft manufacturer Lockheed Martin, according to the Dallas Observer. Hummel died at home, two years after he received a cancer diagnosis. The bassist was 59.

Big Star had to toss out a member after he was accused of assault

After the death of Andy Hummel in 2010 (per the Dallas Observer), the last surviving member of Big Star is drummer Jody Stephens. He played on every Big Star album, and after the band's demise, collaborated with musicians who were influenced by his old group, including Jeff Tweedy from Wilco in the supergroup Golden Smog, and Ken Stringfellow of the '90s alternative rock band the Posies, who was hired by Stephens to front Big Star after the deaths of the other members.

According to Rolling Stone, that arrangement ended abruptly in October 2021, after three women alleged Stringfellow of various and severe forms of sexual assault and abuse. Stringfellow denied any wrongdoing, but the Posies immediately started the process of breaking up, and so did the latest incarnation of Big Star. "I believed them," Stephens said about the allegations in a statement via the Big Star Instagram page. Big Star, in any form, hasn't played live since.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).