Why The US-Canada Border Is Where It Is

The border between the United States and Canada is the longest international border in the world, according to the Government of Canada. At around 5,525 miles (per Atlas Obscura), it roughly follows the 49th parallel from the Strait of Georgia along the Pacific coast to Lake of the Woods between the U.S. state of Minnesota and the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Manitoba, according to History. It then moves from the northernmost point of Lake of the Woods to Lake Superior, from Lake Superior to the St. Lawrence River, from the St. Lawrence River to the source of the St. Croix River roughly along the 45th parallel, and from the St. Croix River to the Atlantic Ocean (via the International Boundary Commission).

There is also a portion of the border that divides Alaska from the Canadian provinces of British Columbia and the Yukon, which largely follows the 141st Meridian from the Arctic Ocean in the north to Mount St. Elias in the south. The U.S. and Canadian border has an equally long and meandering history, which began when both nation-states were British colonies. Its current trajectory, much like the development of those countries, largely ignored the movements of the Indigenous groups that first inhabited North America (per Canadian Geographic). In fact, there isn't a single indigenous group whose historic territory falls only within contemporary Canadian borders.

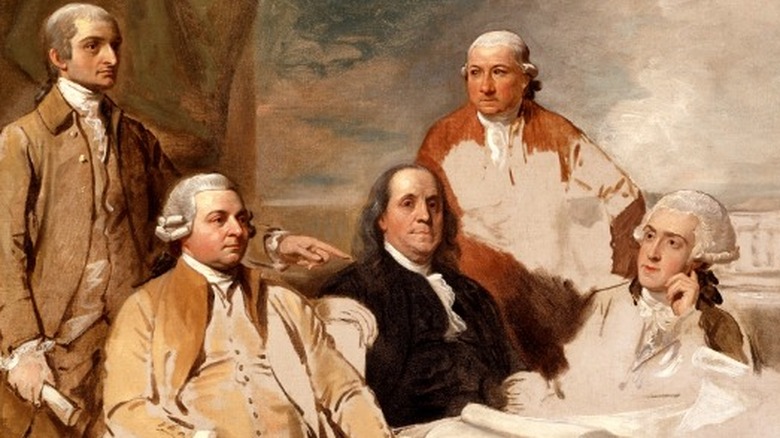

Treaty of Paris

The eastern portion of the border between the U.S. and Canada was established upon the signing of the Treaty of Paris of 1783, which ended the American Revolution and formally recognized the divorce between Great Britain and the 13 colonies that became the United States (per History). That treaty set the boundary between the new nation and remaining British territory. "And that all Disputes which might arise in future on the subject of the Boundaries of the said United States may be prevented, it is hereby agreed and declared, that the following are and shall be their Boundaries," the second article of the treaty read.

That treaty defined much of the contemporary Canadian border between the Atlantic Ocean and the Lake of the Woods. After that point, the border extended west to the Mississippi River and then south along the river, according to the International Boundary Commission. The portion of the border along the 45th parallel had already been established as the border between what were then the British colonies of New York and Quebec in the 1760s, according to The Globe and Mail. However, the surveyors didn't do a very good job — the line actually rarely touches the parallel and has come to be dubbed the "false 45th."

The 49th Parallel

A series of treaties at the turn of the 19th century expanded and refined the border, according to the International Boundary Commission. The 1794 Jay Treaty sent a commission to investigate which river was actually the St. Croix and refine the boundary between Lake of the Woods and the Mississippi. The 1814 Treaty of Ghent commissioned a study to refine the boundaries between Maine on the U.S. side, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia on the Canadian side, and between the 45th parallel and Lake of the Woods. But the biggest shift to the status quo came with the Convention of 1818, which extended the northern border westward from Lake of the Woods along the 49th parallel to the Rocky Mountains.

According to History, that convention included one big question mark: What would become of Oregon Territory? Oregon Territory was much larger than the contemporary state of Oregon. It stretched from the Pacific Ocean to the Rockies and included much of what is today Washington, Oregon, and British Columbia, according to the Office of the Historian. At one point, Britain, the U.S., Spain, and Russia all wanted a piece of it. By 1819, Spain had given up, but the U.K. and the U.S. were still playing diplomatic tug-of-war. The U.S. wanted to divide it along the 49th parallel from the Rockies to the Pacific, while the Brits wanted the border to extend west to the Columbia River and then use the river as the dividing line.

The Oregon Treaty

When drawing up the Convention of 1818, the U.S. and Great Britain couldn't decide what to do about Oregon Territory, so they approached the choice like indecisive people everywhere — they put it off, according to History. At first, the decision was delayed for 10 years. Then, in 1827, they decided to procrastinate indefinitely, according to Office of the Historian. However, by the early 1840s, it became clear that some sort of agreement was necessary as more U.S. residents began to head west along the Oregon Trail.

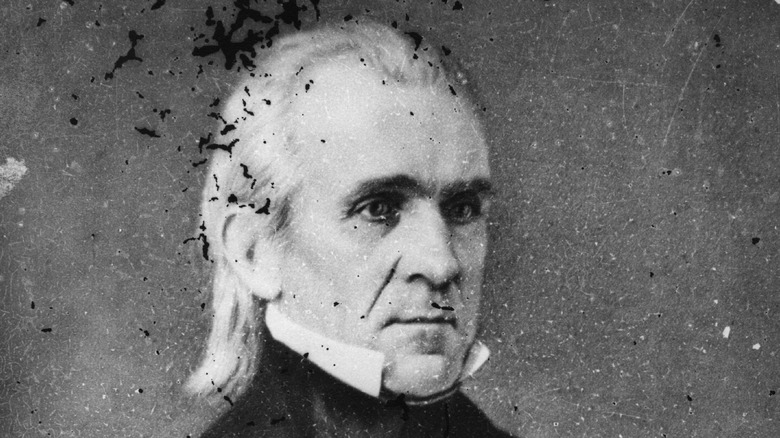

The 1844 victory of Democratic President James K. Polk also pushed the issue. Polk was a firm believer in Manifest Destiny, or the idea that the U.S. should control all of North America "from sea to shining sea" (via History Today). During his campaign, he promised to annex both Texas and the Pacific Northwest, according to the Washington State Archives. Not content with 1818 ambitions, he wanted all of Oregon Territory for the U.S. His campaign slogan was "Fifty-four forty or fight." When he won, Britain grew concerned about the prospect of fighting and sent spies across the Colombia River. At the same time, Polk didn't believe he had won the election by enough votes to have a mandate for war. In the end, the two nations compromised with the 1846 Oregon Treaty that continued the border along the 49th parallel from the Rockies to the Pacific (per History).

The pig war

The Oregon Treaty wasn't the final say. According to Historic UK, the treaty said the border should run through the channel between Washington state and Vancouver Island, but what about the islands in the way? One of these islands was San Juan. Both nations thought it should belong to them, and citizens from both made their homes there. The two communities lived in relative harmony until June 15, 1859, when a British-owned pig wandered onto a U.S. farm and began chowing down on potatoes (per Historic UK). Farmer Lyman Cutlar shot the pig in anger, and the pig's owner, Charles Griffin, wouldn't accept his $10 compensation. Instead, British authorities threatened to arrest Cutlar and kick all 18 U.S. citizens off the island, according to the National Park Service.

What followed was a comedy of errors in which both sides called in increasing military reinforcements until commander-in-chief of the British Navy in the Pacific, Admiral Robert L. Baynes, put his foot down, saying (via History UK) he refused to "involve two great nations in a war over a squabble about a pig." Eventually, higher-ups in both countries learned of the situation and decided to each keep a small military presence on the island until its fate could be decided. This didn't happen until 1872, when Germany's Kaiser Wilhelm I determined the island should go to the U.S. after being asked to decide the matter, according to the National Park Service.

Salmon wars

When the U.S. purchased Alaska from Russia in 1867, and British Columbia officially joined Canada in 1871 (via The Canadian Encyclopedia), a new border was in need of demarcation, according to the BBC. This grew especially urgent when gold was discovered in British Columbia and Yukon territory. Because the easiest way to access the gold was by sea along the border, the two countries needed to define the line so that Canadians could travel freely and the U.S. wouldn't lose any land. This was done via the Alaska Boundary Tribunal of 1903, with all boundaries set by 1905, according to the International Boundary Commission.

However, one part of this border remains in dispute: the Dixon Entrance, according to the BBC. This is a body of water between British Columbia's Haida Gwaii islands and the Alaska panhandle. The southern border between the two countries is known as the A-B line. The Dixon Entrance sits below it, but the U.S. argues that the line only applies to land masses and that it should control half of the strait. The reason? Salmon. Both countries want access to the fish that swim up the strait every year to spawn. Tensions between both nations' fishers got so intense in the 1990s that it was dubbed a "salmon war," according to ABC News. At one point, Canadian fishing boats actually blockaded an Alaska ferry. The conflict ended with a new quota system in 2001, but the Dixon Entrance remains in legal limbo.