The Shameful History Of Antisemitism In America

For many Jewish people, America seemed to be the dream they would inhabit after waking from the European nightmare. It was a country seemingly free of pogroms, ghettos and gas chambers, a place almost drunk on its own self-mythologizing about freedom and equality. For those pulling into New York Harbor, the Statue of Liberty didn't promise a fantasy — it was a waiting reality, perhaps one too good to be true.

According to My Jewish Learning, as far back as the 17th and 18th century, Jews in America were establishing communities and patterns of worship — things that then, as now, they had to fight for. It should not have been the case. Article VI of the United States Constitution says that tests on the basis of religion will not be used in elections to the American office, implying a precedent that meant even minority groups could work their way up the ladder, free from the prejudices of the "Old World." President George Washington even wrote a letter to the Hebrew Congregations of Newport in Rhode Island in 1790, promising an end to bigotry, as per the National Archives. Yet it wasn't to be.

From exclusion zones, to lynchings, synagogue shootings, and attempts at expulsion, antisemitism has flourished in America. While some dangers have been consigned to the past, the world of social media has been a breeding ground for the Far Right. Racism has morphed into new and insidious shapes. It's a sobering warning to all that it was never dead, merely sleeping.

Treatment of sephardic refugees in New Amsterdam

The earliest-known Jews to arrive in the U.S. came in the mid-17th century. New Amsterdam, the Dutch colony that would one day become the state of New York, saw Jews making a permanent home after being expelled from Brazil in the wake of Portuguese conquests in Latin America, according to historian Jonathan D. Sarna in his book, "American Judaism." Most were sephardic (via My Jewish Learning). Initially they came in small numbers, with only 23 sephardi refugees, all men, arriving from Recife, a city in northeastern Brazil, in 1654.

Their experiences were mixed, to say the least. Sarna describes how the governor of the colony, Peter Stuyvesant, an elder of the Dutch Reformed Church, was sympathetic to widespread fears that granting rights to religious minorities would force the colony to give equal status to Lutherans and Catholics, encouraging non-conformism. Furthermore, he described the Jews as "deceitful," "repugnant" and "blasphemers of the name of Christ" — the latter being an accusation that would dog Jewish people across the world for many centuries to come. The sephardi community found themselves having to petition for the right to work and live without expulsion from New Amsterdam.

However, the powerful merchant body Dutch West India Company demanded they be allowed to stay due to the financial support they enjoyed from their Jewish shareholders. Jews were ultimately allowed to trade, worship, serve in the military, and own property. The colony was forced to become more tolerant, allowing people to practice their beliefs so long as they didn't flaunt them or prompt an uprising.

Scapegoating in the early 19th century

The 18th century promised progress. In 1740 naturalization laws were brought in, meaning Jews and other Protestant groups could enjoy legal protections most European countries would not offer for many decades, as per the Anti-Defamation League (ADL). At least five settled Jewish communities existed along the Atlantic seaboard by the time of the American Revolution.

Between 1830 and 1860 around 200,000 Jewish people fled discrimination in Europe in the hope of better opportunities, and, according to John Higham's "Send These To Me," this included a wave of Jews who left Germany in 1830. The Jewish population in America up to this point was small, at less than 15,000; yet the new arrivals were a source of consternation among their "gentile" neighbors. As thd ADL notes, the surnames, behaviors, and modes of speech displayed by newly arrived emigres were distinctive and separate to many Americans, thus making them prime targets for blame.

Although Jews were not formally excluded from American institutions, they became a prominent part of the money-brokering trade and the textile industry. Many became wealthy merchants, writes Higham. Stereotypes about Jews being duplicitous and money-obsessed therefore found a home in the U.S. Many also found that European "race science" would hold them back in America. From 1850 onwards, French scholars such as Edouard Drumont and Joseph-Arthur de Gobineau espoused the belief that Jews were incapable of being creative or dynamic, with distinct physical features and only equipped to be merchants or bankers. These ideas traveled stateside, with disturbing results.

The Civil War

The Civil War saw American society plunged into chaos, and with it came an increase in scapegoating. Jews were blamed by both Unionists and Confederates for assisting the opposing side and profiting off the war, as per the ADL. This was despite the fact that Jews fought on both sides, according to historian Jonathan Sarna in "American Judaisim: A History." The ADL highlights how cartoons in American newspapers painted Jews as opportunistic tycoons, bereft of patriotism and willing to sell vital supplies for the armed forces at inflated prices, thereby lining their pockets by siphoning funds from the war effort.

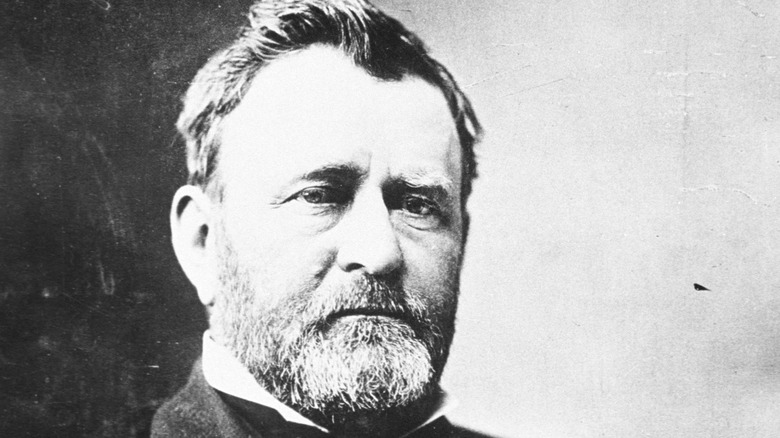

Ulysses S. Grant, the commanding general of the Union Army and future U.S. president, even accused American Jews of cotton speculating and smuggling — illicit antics being done by a whole range of people. His (successful) attempts to have Jews expelled from Paducah in Kentucky and from northeastern Mississippi led to an intervention by President Abraham Lincoln. He made the enlightened comment that "a few sinners" could not be used to cast judgment on an entire group of people. The expulsions were stopped.

Grant later took a similarly enlightened step, one rarely seen in the history of antisemitism — he changed his mind. After realizing he was in the wrong he apologized, notes The Atlantic, and, according to Jonathan Sarna in "When Grant Expelled the Jews," he insisted he would become an advocate for Jews and ultimately human rights. He became a champion of religious freedom in America. It was an encouraging example of the ability to turn away from antisemitism, although it set no precedent.

Suspicion of those escaping the pogroms

After the assassination of Russian Czar Alexander II in 1881, Jewish communities were increasingly used as scapegoats. Many faced hostility and exclusion, ranging from the ransacking and destruction of Jewish homes and businesses to outright violent attacks from non-Jewish Russians. According to the Jewish Virtual Library, in 1882 the government passed mandates that were designed to protect Russians from the Jews by forcibly relocating many to the Pale of Settlement, a remote area on the eastern edge of the Russian empire. Jews were not only cast out of major Russian cities but were excluded from schools and universities and forbidden from studying the law or working in government. The outcome for many was either to accept economic impoverishment, abandon their faith, or emigrate. Millions chose the latter.

Between the 1880s and the 1910s, Jews who fled eastern Europe went to the U.S. in droves. The ADL describes how 85% of the 2 million who arrived went through New York, and many settled there, being too poor to go anywhere else. Some found acceptance; yet historian Leonard Dinnerstein highlights in "Antisemitism in America" that supposedly reputable journalists painted Jewish immigrants as unable to assimilate, imposing their greedy and opportunistic ways upon American society. Writers like Burton J. Hendrick accused Jews of being so obsessed with penny-pinching that they wouldn't provide for their families. It contradicted evidence from community workers in New York, who found that Jews were often in better physical health than their neighbors and enjoyed lower infant mortality rates.

Southern populism

Outside of New York, antisemitism was a popular trope among charlatans and demagogues. Historian Hasia R. Diner's "The Jews of the United States, 1654 to 2000," highlights how Jews became convenient scapegoats, blamed for conspiring with bankers to wreck the livelihoods of small-scale farmers between the 1870s and the 1890s, when southern and midwestern states were beset by bouts of economic hardship long before the Great Depression of the 1930s. As it was taken for granted that Jews ran the banking system, they were assumed to be using the gold standard (a system designed to stabilize the value of a currency by pegging it to a certain quantity of gold, as outlined by Britannica) to further their own ends and keep the rest of the country in poverty.

Those who lived in the cities in particular were seen as undermining core American values in this way and spreading decadence and corruption. It was further proof to many that Jews had divided loyalties and could never be truly American. According to the ADL, Jews were actively seen as a national threat.

This could lead to violence. As Diner writes, in the 1890s southern mobs targeted Jewish shopkeepers, with one attacker claiming the carnage was justified due to a dubious claim that the Jews and others owned a majority of their land. This poisonous legacy of antisemitism in the southern and midwestern states were a catalyst for other bouts of anti-Jewish violence — with one particular man, Leo Frank, being immortalized for the worst possible reason.

The lynching of Leo Frank

Leo Frank was a Jewish-American factory superintendent from Atlanta, Georgia, who was accused of murdering a girl who worked for him, in a case that became a gruesome testament to the legacy of antisemitism in America. As described by the American Jewish Archives, his trial in 1913 for supposedly murdering 13-year-old Mary Phagan, a girl who worked for him at the Atlanta National Pencil Factory, was highly inflammatory and biased against Frank due to his religion. He was handed a death sentence, and although his appeal went all the way up to the Supreme Court, there was a 7-2 vote in favor of imposing the death penalty.

The governor of Georgia at the time, John M. Slaton, overturned the sentence in 1915 due to concerns about flawed evidence, according to the ADL. He commuted it to life in prison, a move that led to widespread outrage. Frank was kidnapped from jail by a white supremacist group called the Knights of Mary Phagan and hanged from a tree, notes the Jewish American Archives — a horrifyingly common practice across the South. Photos were taken of his suspended corpse (later sold as postcards, according to the ADL), and the men involved composed a song called "The Ballad of Little Mary Phagan." Their violent act also marked the resurrection of the vigilante group the Ku Klux Klan. None of the murderers were ever convicted.

Frank was later given a posthumous pardon in 1986, according to The New York Times. As with numerous victims of antisemitism, it was too little, too late.

Revolution and the fear of Bolshevism

The murder of Leo Frank led many American Jews to fear for their lives. In 1915 around 1,500 Jews left Georgia, while one synagogue in Atlanta adopted the strategy of keeping a low profile to avoid being targeted (via the Jewish Virtual Library). According to historian Jonathan Sarna in his book, "American Judaism," major global events such as the Russian Revolution in 1917 and the outbreak of World War I meant that levels of hostility rose towards German-Americans and Jews. The fear of Bolshevism was high, and immigrants were often accused of undermining national stability and American values. According to one rabbi, the aftermath of WWI saw a wave of antisemitic literature being published.

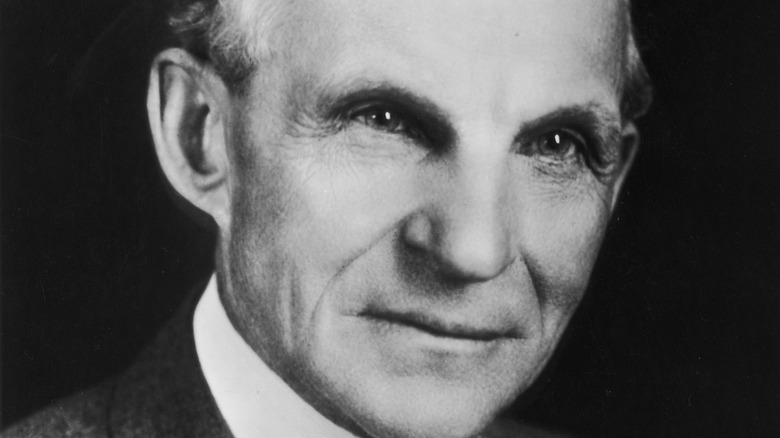

Some notably sinister and high-profile examples, according to Sarna, included businessman Henry Ford's weekly newspapers, which in its late-1920 print run drew heavily on "The Protocols of the Elders of Zion," a 1905 antisemitic tract posing as a Jewish manifesto. By synthesizing his beliefs in a four-volume work titled "The International Jew," Ford helped to spread ideas about an international Jewish conspiracy threatening to overwhelm America, citing the smothering influence of Jewish values and culture, especially in the cities.

There was pushback against Ford's propaganda. In 1927 he apologized belatedly for continuing an inflammatory narrative and for claiming that "the Jews have been engaged in a conspiracy." But his ideas helped to entrench the suspicions of many that their Jewish neighbors were insufficiently patriotic, loyal only to subversive international networks or narrow sectional interests, and had never fully contributed to America. In short, they could not be trusted.

The Ku Kux Klan

According to "They Called Themselves the K.K.K." by Susan Bartoletti, the Ku Klux Klan started out as a group of unsatisfied Confederate veterans in the 1860s, who modeled their club after a disbanded southern fraternity and dressed as ghosts to scare people. Initially these men were looking to stay occupied, as the end of the Civil War left many ex-soldiers in the southern states feeling purposeless and adrift. They knew that railing against the government was pointless, so they channeled their energies into forming secret societies that had bizarre rituals and dress codes. Although the KKK harrassed freed people, their aims were allegedly not explicitly racist. But as the New Georgia Encyclopedia details, they terrorized Black and their white supporters, often through violence, until the group faded away after the Civil Rights Act of 1871 and subsequent trials to prosecute klan members.

As Bartoletti notes, when the 1915 film "Birth of a Nation" glorified the KKK, it prompted their rebirth. However anti-Black sentiment was not enough to help the group flourish in the north, so they warned against the Jews, immigrants, and Catholic, who they claimed were bringing in degenerate influences such as sex, alcohol, and jazz music, writes Linda Gordon in "The Second Coming of the KKK."

The KKK practiced a number of terrorist activities designed to cause terror and intimidation for anyone they saw as threatening the Aryan race, including public lynchings. At the time their views were not considered fringe — they were widespread and condoned, making life terrifying for Jews living in areas where the KKK were active.

Exclusion from civic life

The ADL highlights how American Jews were barred from many parts of civic society, including universities in the Ivy League, private elementary and high schools, and holiday destinations. Historian Jerome Karabel states in "The Chosen" that Harvard University was under pressure to impose a quota of Jewish students in 1922, proposing to limit them to 15% of the student population, while Jewish students that did attend often found it hard to join college social groups, especially prestigious ones. Upper-class German Jews like Walter Lippman criticized Jews who had previously been poor and now chose to show their wealth. He made the bizarre claim that they were to blame for an increase in antisemitic resentment and could only expect to counter this by downplaying their heritage and blending in.

His views were shared by many other elite universities. Jonathan Sarna claims in "American Judaisim" that Yale, Princeton, Columbia, Johns Hopkins, Duke, and Northwestern were among those who actively capped Jewish student numbers in the 1920s, as did many private schools. Explicit discrimination was widespread in luxury hotel resorts, private members clubs, and new housing developments, which were often brazenly advertised as "exclusively for gentiles."

The Jewish Telegraph Agency describes how a law banning Jews in Florida from being able to own property was only reversed in 1959. It came about after a man based on Sunset Island in Miami was denied membership of a home-owners association due to his religion. Other members of the association had tried to have him removed from the island but ultimately failed.

Nazi sympathisers in the 1930s

With the rise of the Third Reich in 1930s Germany, American fascists sought to bring Nazism to the U.S. According to cultural historian Sarah Churchwell (via the Lawfare podcast, they were disorganized and never took power, but their sympathy for fascism dovetailed with their support for Jim Crow. This in turn was used by the Nazis to formulate their own anti-Jewish practices. In other words, Adolf Hitler learned from the American Right, and vice-versa.

As described by the ADL, the pro-Nazi German-American Bund held a hugely popular antisemitic mass gathering at Madison Square Gardens in 1939, an event attended by thousands. In the same year, opinion polls from the Public Opinion Quarterly showed that a majority of Americans (around 60%) thought that Jews shouldn't be seen on the same terms as their other countrymen.

Many people still believed that Jews were deceitful and even criminal, due to high-profile Jewish involvement in prohibition-era bootlegging and match-fixing in sports, due to the notoriety of figures like Jewish mob boss Arnold Rothstein (via Jonathan Sarna's "American Judaism"). It didn't help that antisemitic sentiments were common among figures like industrialist Henry Ford, who said the 1919 World Series scandal was due to malevolent Jewish influences. Father Charles Coughlin, a priest and populist leader, published antisemitic tracts in the 1930s containing pro-Nazi opinions, having stated that Kristallnacht was a valid push-back against Christian oppression by Jews, according to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. He received thousands of fan letters and millions of listeners each week to his radio broadcasts.

WWII and isolationism

The aviation hero Charles Lindbergh railed against Jews, claiming in 1941 that their supposed control of American media and politics was a far bigger threat to the U.S. than the Nazis, as per The New Yorker. In a 1939 diary entry (via Intelligencer), Lindbergh said that he felt "a few Jews add strength and character to a country, but too many create chaos," and that his country was becoming overpopulated. Not long before America joined the war effort, he lobbied in Congress against the Lend Lease Act, which allowed American financial support to go to countries fighting for the Allies (via History). Lindbergh was also a member of the America First Committee, notes Esquire, which pushed for the U.S. to avoid aggression against Germany. The ADL talks of how he was among many Americans who blamed Jews for dragging them unnecessarily into a European war.

The feeling that America had too few jobs after the Depression had fuelled further xenophobia and antisemitism, and the sense that America had "too many" Jews had already seen heartbreaking consequences for refugees fleeing the Holocaust, describes the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. German Jewish refugees trying to enter the U.S. on a ship named the St Louis were turned away when they tried to land in Florida in 1939. A number were taken in by Britain, France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, and some did eventually get visas to the U.S. However, when Germany invaded all but Britain, 254 of the original passengers were killed in the ensuing Nazi genocide.

The Civil Rights Movement

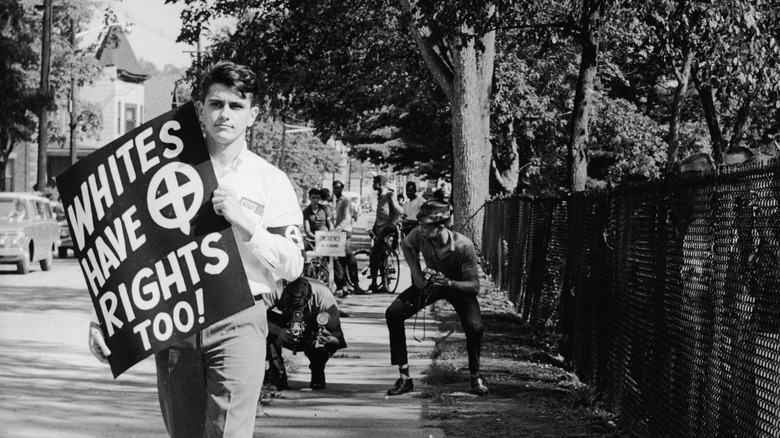

American Jews were involved in the civil rights movement of the 1960s, which meant white supremacists targeted both Jews and Black people in a racist backlash (via the ADL). The founder and leader of the American Nazi Party, George Lincoln Rockwell, called for Jews with communist sympathies to be gassed the way European Jews were in the Holocaust, as highlighted by The Washington Post. Rockwell also generated the phrase "white power" in 1967, which became a favorite among American far-right groups and even wrote a book of the same name that was published after his death. In 1960 he had stood outside movie theaters screening the film "Exodus," about the early days of the Israeli state, while wearing a Nazi uniform. Throughout the 1960s he attended demonstrations for the desegregation of housing while holding up signs claiming most communists were Jewish and that "racial mixing" was a pernicious conspiracy bankrolled by Jews.

Jewish centers and synagogues were bombed during the 1950s, '60s, and '70s by white supremacists. Notable incidents, according to The Atlantic, included the 1958 bombing of Atlanta's oldest synagogue, the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation (where thankfully no one was hurt), and the attempted bombing and gun attack against attendees at the Temple-Beth Israel in Gadsden, Alabama, in 1960. No one was killed, but the attacker injured two people as they tried to leave. In 1977 another gunman attacked the Brith Shalom Kneseth Israel synagogue in St Louis, Missouri, where one man was killed and two others were injured.

A changing century

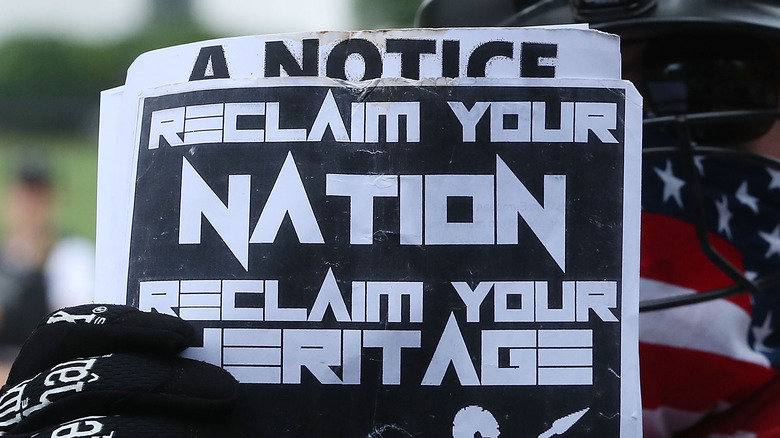

The Hill maintains that the worldwide collapse of the banking industry in 2008 laid the groundwork for a resurgence of antisemitism in America. Rising inequality, economic instability, and the cultural changes and pressures brought about by globalization have led to the resurgence of sinister stereotypes about Jews conspiring with global elites and undermining America from within, notes the ADL. Accusations about Jews having divided loyalties continue to abound, as the rejection of international financial institutions has ushered in tropes that paint Jews as architects of self-interested global networks of power. Furthermore, as The Hill reports, the resurgence of religious fundamentalism in the early 21st century has led to many people thinking that America is under siege from forces threatening to undermine the country's core values, by people who choose duty to faith over duty to country.

Multiculturalism and globalization, forces hastened by rapid technological change, have undermined the certainties of many. Faced with a bewildering, incomprehensible and ever-changing world, antisemitism is an easy fallback for those who want a scapegoat for their complicated woes, according to the ADL.

Even before the 21st century, technology was helping antisemitism to flourish. With the advent of the World Wide Web, message boards such as Stormfront became places where antisemitic images and ideas could flourish, as highlighted by the Southern Poverty Law Center. Yet this has paled in comparison with the rise of social media, which has seen the views of far-right groups flourish like never before.

QAnon and the alt-right

The influence of social media, a 21st century-phenomenon, has inflated the influence and reach of far-right groups that continue to blame Jews and others for America's political and economic woes, as described by the ADL. Social media platforms like 4chan and 8chan not only became petri dishes for Nazi symbolism but spawned movements like QAnon, which Haaretz outlines as a network of conspiracy theorists claiming Jewish elites are part of a secret group of pedophiles. It echoes the "blood libel," an ancient conspiracy theory claiming that Jews feed on Christian children's blood.

The Washington Post describes how in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017 a group of Far Right protesters gathered and chanted "Jews will not replace us!" and "White Power!" According to The Atlantic, this and recent gun attacks on synagogues have made Jewish groups feel increasingly targeted. In 2018 there was a deadly shooting at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, where 11 people were murdered and six more were injured. Prior to this there were attacks on Jewish groups and buildings in 2014 (in Kansas, where three people were killed), in 2009 (at the Holocaust Museum in Washington, where one person died), and in 2006 (at the Seattle Jewish Federation, where one person died).

As recently as January 2022, The Guardian reported on a hostage situation where a man took four people hostage during a live-streamed service at the Congregation Beth Israel synagogue in Texas. The gunman died, but everyone else survived.

Anti-Zionism

It's been common to assume that antisemitism is a phenomenon of the Far Right, but antisemitic activity has also been a factor of some groups on the left, particularly those who paint Jewish groups as one united and malicious force (as shown by The Washington Post) — despite the wide range of beliefs, opinions, and philosophies within Jewish communities.

NBC News describes how disagreements over the Israeli-Palestinian conflict have led to some Jews being expelled from other civil rights marches, such as LGBTQ+ parades, whenever they have displayed flags showing the Star of David — a symbol long associated with Jewish people but which has drawn ire for being linked with Israel. This stance has been seen as deeply problematic on many sides, as it assumes Judaism and Zionism are one and the same but also skates over how deeply offensive many Jews find it that the disagreement with Israeli politics has become bound up with calls to get rid of Israel — a move that would leave many Jewish people stateless. Civil rights activists have said that political disagreements over Israel should not erupt into outbreaks of antisemitism.

Some of these eruptions have embraced some deeply sinister tropes. Tweets were unearthed by the Star Tribune that showed the owner of an LGBTQ+ bar in Minneapolis had called for Israelis to perish and accused Zionist Jews of exerting undue influence over the U.S. Such moments have served as a sobering reminder that antisemitism is not exclusively a Far Right phenomenon.

Celebrity controversies

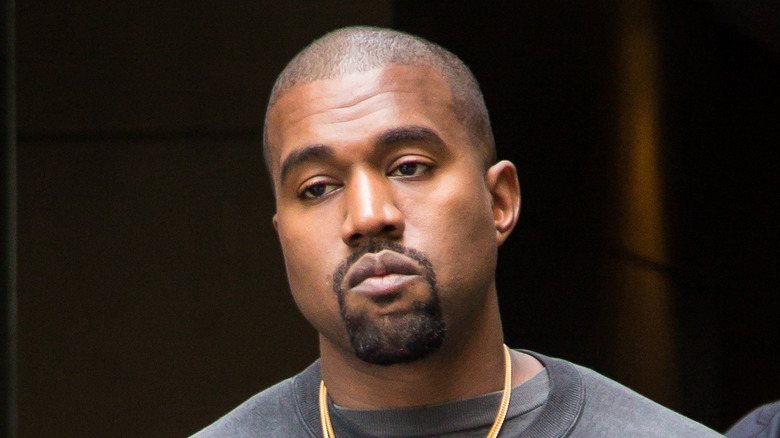

The American rapper Kanye West or Ye, known for his controversial views, was dropped by sponsor Adidas in 2022 due to his antisemitic outbursts, as reported by New Statesman. He tweeted that he would "go death con 3 on Jewish people." West provoked outrage, not least because as the journal Language Sciences highlights, he was criticized in 2015 for saying that "Black people don't have the same level of connections as Jewish people."

Celebrity antisemitism in America has a depressing track record. Business Insider draws attention to actor Charlie Sheen's antisemitic rant against writer Chuck Lorre in 2011, calling him "Chaim Levine" (a mocking reference to his Hebrew heritage). Newsweek details how actor and director Mel Gibson has made multiple comments against Jewish people through the years, including blaming Jews for all the world's wars after being stopped for drunk driving, and saying the words "oven-dodger" to actor Winona Ryder. Pop singer Miley Cyrus was accused of antisemitism in 2013 when she said that a "70-year-old Jewish man" was deciding what media content should be marketed to young people. The actor, musician, and TV personality Nick Cannon was admonished in 2020 when he claimed the people with all the power included "the Zionists" and "the Rothschilds" (a famous European banking family who were the subject of multiple antisemitic conspiracy theories, according to The Times).

Language Sciences states that these comments echo the centuries-old conspiracy of Jews being "clandestine wire-pullers." It's a sign that antisemitic tropes continue to have a pernicious appeal, despite their horrifying history.