The Crimean War Timeline Explained

The Ukrainian region of Crimea has been a talking point since the invasion by Russia in 2014. Yet, it's a long-beleaguered area. This was mostly due to the events of the mid-19th century, which saw the rising tide of British and French military ambitions cross paths with an expansionist Russia led by Czar Nicholas I. The world could not accommodate the ambitions of all, something which became clearer as the decline of the Ottoman Empire (the Turkish hegemon that had sprawled across Europe and Asia for centuries) looked to be a looming reality. An increasingly fragmented Middle East was up for grabs, and everyone who mattered knew it.

Although on the surface it seems like there were two sides to the conflict, the Crimean War was, in reality, a war with many sides, as everyone had their own set of vested interests. According to Historic UK, France wanted to continue expanding after its conquests in North Africa, while Britain wanted to ensure it had unfettered access to its trade routes with India, something threatened by the powerful Russian navy. Influencing territories controlled by the Turks looked like a guarantee of security and prosperity. France, Britain, and the Ottomans, therefore, teamed up to prevent Russian expansion southward. Religion played a role as much as economics; Russian Orthodox and French Catholic interests competed for control of the Holy Land, and neither side was prepared to back down.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the themes of the Crimean War seem more relevant than ever.

February - May 1853: Diplomacy breaks down

Tensions might have been simmering for years, but they were met with genuine diplomatic efforts. Czar Nicholas I wanted to quell the belief that he was interested in global expansion, showing France and Britain that he was only concerned about Christians in the Ottoman-run Holy Land, whom he was convinced were being treated as second-class citizens. In 1853 he sent his diplomat, Prince Alexander Sergeyevich, to the Ottoman sultan with an ultimatum — that Russia be granted dominion over the 12 million Christians living in the Ottoman Empire (via Historic UK).

Britain initially acted as a mediator between the two sides. For a while it looked as though war might be averted; but, according to TheCollector, Russia had already spent much of the preceding century swallowing Turkish territory. Insecurities among the Ottomans ran high, and Britain had a vested interest in using them to keep Russia at bay, fearful that the czar would eat into British-controlled territories. Stratford Canning, British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, petitioned the Ottoman sultan to reject the treaty when Russia seemed to be making further demands (via Britannica).

The Ottomans had already agreed to the Treaty of Adrianople in 1829, which gave Russia access to the Mediterranean through the Black Sea Straits. However, in 1852, the French ship Charlemagne sailed into the Black Sea, incensed over the sultan's refusal to give the French responsibility for Christians in the Holy Land. Under pressure from the British and the French, the sultan broke the Ottoman Empire's agreement with Russia.

June - September 1853: Tensions rise

Once the ultimatum from Russia was denied by the Ottomans, Russia broke off diplomatic ties. In mid-1853, Czar Nicholas I sent an army to Moldavia and Wallachia, Danubian principalities under the control of the Ottoman Empire. According to Kafkadesk, his aim was to stop the British and French from having any kind of sway over the conflict with the Turks.

The strategy didn't work. In July, Britain sent a fleet of ships to the Dardanelles to support Turkish military efforts. The French had done the same thing, and Britain wanted to show support. Before long, Turkish forces were trying to resist the efforts by the Russians to make incursions along the Russo-Turkish border, reinforced by Britain. Two months later, in September 1853, the British fleet was ordered to set sail for Constantinople, the Ottoman capital. The prospect of war was looking increasingly unavoidable.

One of the reasons diplomatic outreach had failed was because of the pugnacious attitude of Prince Alexander Sergeyevich, an envoy who was, somewhat ironically, not known for having a subtle approach to diplomacy (via Kafkadesk). An ultimatum was unlikely to lead to anything but a backlash. In the context of Turkish unease over Russian expansion, the czar's claims that Russia only cared about preserving the rights of Christians in the Middle East was seen as a smokescreen — an assumption that turned out to be correct. A Europe and Asia at war, and a radically changed world, now beckoned.

October 1853 - January 1854: The Crimean War starts

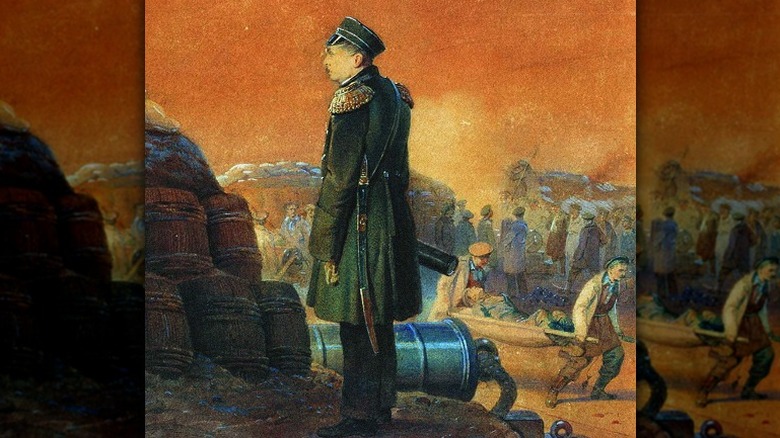

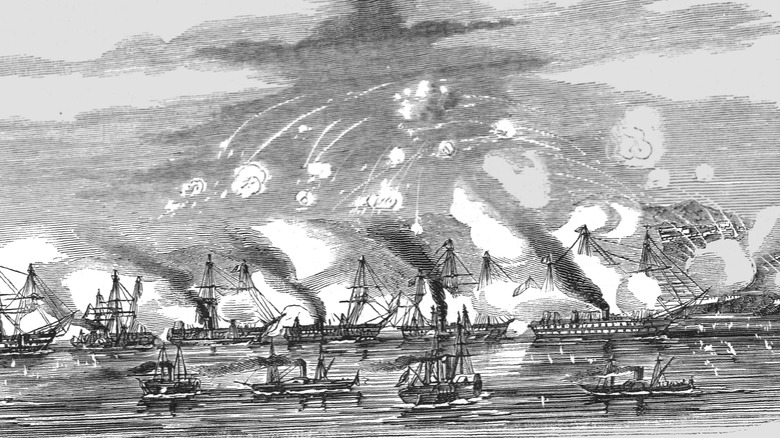

1853 was a fateful year, and before its close, the Ottomans declared war on Russia. Various naval disputes ensued between the two sides, particularly in the Danubian territories and the Black Sea. One of the major skirmishes was the Battle of Sinop, a standoff that the Boris Yeltsin Presidential Library describes as one of the key victories for Russia in the early phase of the war.

Vice Adm. Pavel Nakhimov had discovered the location of the Turkish fleet in Sinop Bay. Rather than just blocking the fleet, the Russian forces were ordered to destroy the Ottomans to prevent them from sailing to the Dardanelles, where Britain and France were stationed and ready to provide reinforcements. The battle lasted for four hours, with Russian artillery fire destroying all but one Turkish steam frigate. Turkish losses amounted to 300 men being shot or drowned, 200 being taken prisoner, and 26 destroyed guns. Among those who were captured by the Russians was Ottoman field marshal Osman Pasha. Russian losses by contrast amounted to 37 dead and 235 wounded.

After the victory, the czar awarded Nakhimov a high military honor, the Order of St. George, 2nd degree. Yet, it would not be plain sailing for Russia. Although the victory at Sinop meant their forces could remain dominant in the Black Sea, it prompted a major, and eventually devastating, outcome — the Allies bringing their forces further into Russia's orbit. In battle terms, things had only just gotten started.

March - September 1854: Britain and France follow suit

The dawn of 1854 saw French and British troops arrive to bolster Ottoman forces after their devastating defeat, and in March, the Turks' European allies officially declared war on Russia. Austria, which had so far been neutral, decided to occupy the swathes of the Danubian region previously held by Russia, but which had been evacuated when they lost to the Ottomans in the summer of 1854 (via the National Army Museum). In September. French forces made the bold, possibly reckless move to sail out of the Ottoman port of Varna without much forward planning. This would become a feature of the whole Crimean War.

In September, the Battle of Alma took place on Russian soil, after British and French troops, deciding they were no longer needed at Varna, arrived at Calamita Bay in the Crimea. They decided to march toward Sevastopol, while Russian forces under Prince Alexander Sergeyevich headed to the Alma Heights in the hopes of finding a decent strategic position. The Allies launched a chaotic and disorganized attack with troops who had been depleted by cholera on the route to Sevastopol.

Yet despite this, the Russians, who had already lost around 5,000 men, retreated in the wake of British advances with rifles and the French on the cliffs at Alma. Against significant odds, the Allies prevailed. Both sides paid a heavy price; around 10,000 soldiers were lost, nearly half of them from the Russian side.

September - October 1854: Sevastopol

September 1854 saw the long march to Sevastopol, the beginning of a relentless series of attacks on the city. There was no clear plan by the Allies, but Sevastopol ended up under constant siege due to its strategic importance. It was the place where the czar's Black Sea fleet was located, a presence seen as deeply threatening to France and Britain due to its proximity to the Mediterranean, and to trade routes and territories they sought to jealously guard. On October 17, the Allies bombed the city six times.

Yet, according to the National Army Museum, the Russians were able to keep defending Sevastopol for longer than they might have, due to the Allies' lack of knowledge about how weak its initial defenses were. British and French forces chose to approach the city from the south, using the Balaklava and Kamiech ports as their launch points. This gave the Russians time to shore up their defenses, ensuring that until the six-time bombing by the Allies, the city stood firm. Even after the constant bombardments, Sevastopol could only be fully taken a year after the military offensive began.

Royal Museums Greenwich highlights how the Russians were thwarted during the skirmishes at Balaklava and Inkerman when they tried to stop further attacks on Sevastopol. Yet for Britain, the war was unpopular and faced mounting criticism at home. The death of many under-prepared troops from cold and disease caused outrage — particularly, as more tactical blunders lay ahead.

October - November 1854: Major blunders

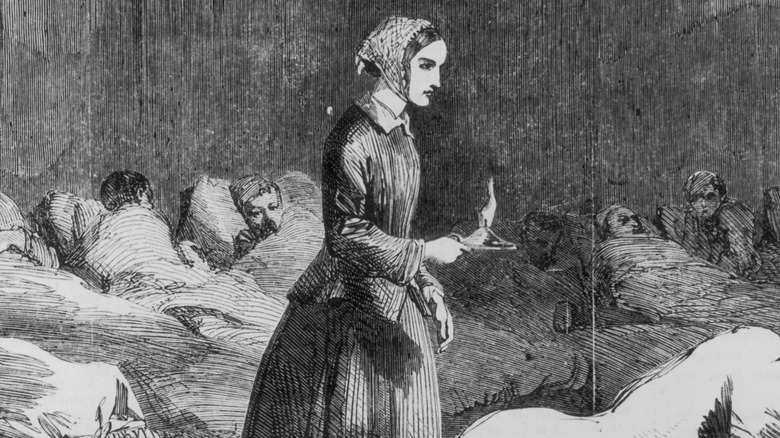

In late October of 1854, the British nurse Florence Nightingale arrived to tend to those wounded in the Crimean War. According to Royal Museums Greenwich, reports of soldiers being riven with disease and lacking basic protections against the punishing climate had stoked high levels of anger back in Britain. Nightingale heard reports of carnage and felt compelled to help. Historic UK describes how she set foot in the Ottoman Empire with 38 other nurses, including a cohort of Catholic nuns. In despair over the staff shortages, lack of funds, and filthy, disease-ridden conditions, she appealed to the British media to call on the British government to provide a solution to the crisis. A hospital was soon built at Renkioi in the Dardanelles, and Nightingale's commitment to high standards of sanitation meant that death rates among the soldiers from disease and infection started to drop.

Later that month, the infamous "Charge of the Light Brigade" took place, a disastrous moment defined by a lack of competent communication and planning, with British soldiers facing shots from three different directions. History Extra highlights how Russian attempts to seize the port of Balaklava were rebuffed, but the British still wished to recover some of their naval guns. The north valley was a death trap filled with Russian gunmen, but the Light Brigade forged ahead. Although the Russian cavalry was ultimately driven back, the barrage of crossfire led to the deaths of 110 British men, while 160 were wounded.

January - June 1855: The Allies make gains

The war caused political turbulence back in Britain. Opposition leader Benjamin Disraeli blamed Stratford Canning and Prime Minister Lord Aberdeen for setting off the conflict, ultimately ending Aberdeen's career (via the National Army Museum). A heavy bombing campaign continued between the Ottomans, the Allies, and the Russians during the first half of 1855. The attacks on Sevastopol were unrelenting, while the Allies made further gains against Russia during the Battle of Eupatoria, a major port city in the western part of Crimea, writes academic Mara Kozelsky.

There was a setback after an Allied attack on Chernaya was ultimately aborted. Russian troops also managed to successfully capture Mamelon, a hillock providing a good strategic vantage point, but the presence of 10,000 Sardinian troops ultimately helped to bolster the Allied campaign — to the point where the capture of Sevastopol looked increasingly likely.

The Jamaican nurse Mary Seacole had arrived in the Ottoman Empire in March 1855 to provide supplies and refreshments to the wounded, ignoring attempts by the British army to stop her from joining the nursing effort. According to National Geographic, once most of the hostilities between the Russians and the Allies were over, she went out onto the battlefields to help the wounded and comfort the dying. Even after the whole war ended, she continued to run a store and restaurant providing a range of cuisines to those desperate for good-quality food. Her efforts were praised in the media almost as much as Florence Nightingale's.

June - September 1855: The siege of Sevastopol ends

In August of 1855, the Russians launched the Battle of Chernaya in an attempt to force an Allied retreat, although the opposite happened — Russia ended up retreating and the Allies made more gains. In a New York Daily Tribune article from the time, Friedrich Engels described how once the Russians were forced back twice across the river, they lacked the extra troop reinforcements to gain victory. The presence of the Sardinian soldiers meant they were easily caught in deadly crossfire from multiple sides. The French had also been given a decent amount of time to build reinforcements, meaning the Russians could not launch a surprise attack. All in all, the Russians lost 5,000 men during the battle, either through being killed, wounded, or captured. The Allies lost 1,500.

Sevastopol was forced to endure a fifth and sixth bombardment in August and September of that year. According to the Royal Museums Greenwich, although the British and French forces failed to make gains at the forts Malakoff and Great Redan earlier in the year, they were eventually captured and subdued in September. The seizure meant that the Russians decided to abandon Sevastopol. In September 1855, they razed their fortifications, sinking their warships and blowing up their forts, allowing the Allies to storm in.

It was a decisive moment in the Crimean War; the loss of such an important territory forced Russia to consider a peaceful end to the conflict.

September - November 1855: The attack on Kars

Difficulties still lay ahead for the Ottoman forces. According to historian Harold E. Raugh, in 1854, the British sent Brig. Gen. Willam Fenwick Williams to assist the Turkish commander Zarif Mustafa Pasha. The Turkish military had retreated toward the fort of Kars after multiple defeats by the Russians. Williams tried to address the flagging morale, bad leadership, and rampant corruption that was endemic at the fort. He brought in fresh supplies, trained around 17,000 soldiers, and built new facilities.

However, a series of attacks and a blockade imposed by the Russians in the summer of 1855 resulted in increasingly short supplies and heavy food rationing. Pasha was also unable to get more troop reinforcements from the Allies. When the Russians attacked again in September 1855, malnutrition and disease, especially cholera, had ripped through the Turkish forces, compounded by the awful weather. Although they held onto the garrison for two months, inflicting 7,500 casualties on the Russians, in November, Williams, who felt abandoned by the Allies, accepted the surrender of Kars. Pasha had already left by that point with a cluster of Russian troops once Sevastopol fell. Although he sent relief efforts to Kars, they didn't reach the fortress in time to prevent the surrender.

More than 18,000 men were made to stand down, and Kars was taken over by Russian forces under Gen. Muravyov. It was yet another example of the poor communication and logistics that had dogged the Allies at every stage.

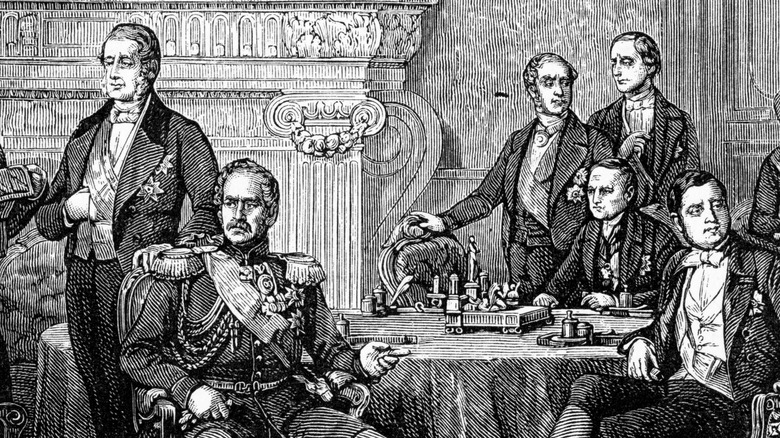

January - February 1856: Russia relents

At the beginning of 1856, Austria openly threatened to join the Allied forces, making Russia uneasy. Although Austria had not fully joined the war effort, writer Togay Seçkin Bi̇rbudak drew attention to Austria's role in trying to pacify Russia and extract Ottoman concessions throughout the Crimean War. The result was that Russia was not able to find a European ally, either diplomatically or militarily. Even when animosity was at its highest, Vienna continued to mediate negotiations between both sides. Austria had even intervened militarily, overseeing the Ottoman territories of Moldavia and Wallachia when they were eventually abandoned by Russia. According to Britannica, Russia agreed to initial peace accords in February 1856.

Both sides had been heavily demoralized and depleted; around 250,000 Allied soldiers had died, along with half a million Russians. The impact of freezing trenches and shortages of food, clothing, tents, medicine, and cooking fuel had contributed hugely to the attrition rates. Many transport animals relied on by the Allies had died of hunger and cold, and muddy roads meant supply lines couldn't be maintained.

Other military campaigns had faced similar issues, but war reporting was a recent phenomenon. It led to greater public awareness and scrutiny of the conflict's failures. On the British side, the lack of supplies was blamed on government inadequacy and bad military administration, as highlighted by the National Army Museum. Despite an Allied victory, it prompted a rethink of how the army was managed.

February - March 1856: Armistice

The Crimean War officially ended in March 1856. The Congress of Paris was launched in late February and a few days later an armistice was declared in the Crimea, followed by the signing of the Treaty of Paris. The Gazette recalls that the treaty provided a written guarantee of Ottoman independence as well as the neutrality of the Black Sea. It was signed by representatives from France, Austria, Britain, Prussia, the Russian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Sardinia.

The result was that warships and other kinds of firearms were forbidden from entering the territory and from gaining access to the shores around it. Furthermore, Russia was required to give up control of Bessarabia, a region near the Danube. The river, therefore, became open to receiving ships from all countries. Ultimately, Russia's dream of southward expansion, including the establishment of a warm water naval port, was scuppered.

A notable outcome of the Crimea War was major changes in nursing, with cleanliness standards from war hospitals becoming the norm all over. However, Britannica points out that the war didn't settle power relations in Europe once and for all. Russian Emperor Alexander II, who had taken over from the previous czar in 1855, realized the need for Russia to modernize if it would compete with the major European powers. Austria also lost Russian support, having backed the Allies, but later found it could not rely on British and French backing in later European conflicts, undermining its power and influence.