What A Victorian Ball Was Really Like

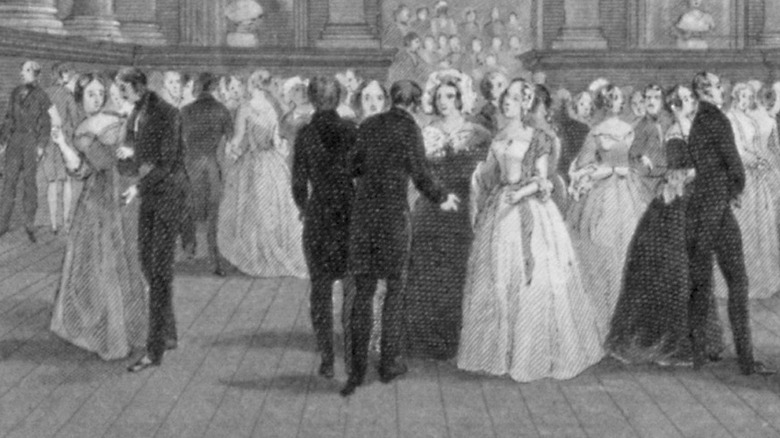

The Victorian era left behind a lingering set of images in the popular imagination: depictions of well-dressed gentlemen and ladies in horse-drawn carriages, fictional legends like Sherlock Holmes or Count Dracula stalking the streets of London in the midst of pea-soup fog, and working-class toil during the Industrial Revolution still impress and captivate. And among these lingering images of a bygone age is the lavish, formal Victorian ballroom.

A ball with couples engaged in partner dancing is a relatively new fixture in the social calendar. Per the Library of Congress, group dancing was the norm well into the 19th century. Groups of couples would engage in well-known sets of steps, or folk dance traditions would be practiced. Something more like our modern conception of the Victorian age started taking shape by the 1830s when rules and regulations for conducting a ball became all the rage among the ascendant middle class. Equivalents of today's self-help or how-to books proliferated, offering aspiring hostesses guides on how best to conduct their dances.

Ballroom guides were less concerned with etiquette by the late Victorian period, and books exclusively dedicated to manners had become more popular by then. Ballroom guides concerned themselves with dancing itself. Group dances retained some popularity, but couple dances grew more common. All the while, balls functioned as an important event for high society, and thus demanded plenty of attention.

Practices were an outgrowth of the Regency era

The ball's importance in Victorian society was a continuation of its function during the Regency era, the long period encompassing George III's decline and the regency of his son. The ball in the Regency period was distinguished from other parties, according to William Parkes' "Domestic Duties," by its featuring dance as the exclusive source of entertainment for the evening. To throw one demanded an exhaustive amount of work even with servants or contractors. Among the preparations was the clearing of furniture and carpeting from the ballroom and decorating the floor with chalk to keep dancers from slipping.

Rules of social etiquette around these sorts of social dances that developed during the Regency continued into the Victorian era, though not without evolution. As the middle class became more prosperous over the 19th century, etiquette was a way for the nobility to distinguish themselves, and for the middle class to climb higher up the social ladder (per the American Antiquarian Society). Adherence to the rules of etiquette at formal balls was taken as a sign of one's conduct in general life, and one's prospects as a friend or potential marriage partner. The Regency era was also when couple dances slowly began establishing a presence, according to dance historian Richard Powers (via Stanford). Initially carrying the whiff of scandal, they became common by the 1850s.

Finding a venue could be tough

Where does one host a ball? In a ballroom, of course. But finding one, or an appropriate substitute, wasn't always easy for the Victorian party planner. Per History Today, dancing's popularity in the 19th century put a high demand on available spaces. Pubs rented themselves out, private houses became clubs, and pleasure gardens hosted outdoor dances during the summer.

A problem many party planners ran into was licensing; without a magistrate's sign-off, it was technically illegal to host a public dance, and authorities didn't hesitate to close down household balls. A popular dodge around this requirement was to claim that a given venue was actually a school of dance that gave lessons free of charge. Some such schemes actually did offer lessons, though whether they would do students much good during the "school's" regular balls was touch and go.

By the 1840s, the growing popularity of couple dances like the polka led to the earliest all-year nightclubs, though they struggled to overcome an association with prostitution when applying for licenses. More successful were the ballrooms included in civic buildings built in the mid-to-late Victorian period and dedicated conservatories at popular resorts.

It took a committee to plan a ball

Today, planning committees for parties seem reserved for public events, and so it was for the Victorians. "The Ball-Room Guide" from Warne's Bijou Books, laid out various types of public balls and explained some of the various offices needed to properly organize and run them, for which a committee was often pressed into service. Tasks included securing a venue, distributing invitations and admission tickets, having a steward or a patroness check said tickets, and finding a master of ceremonies to arrange introductions among guests.

Most modern public parties aren't quite that regimented, and the invitations for private parties are typically just sent out via social media. But, as Victoriana Magazine found after combing through various 19th-century ballroom guides and books on etiquette to paint a picture of the private Victorian ball, careful planning by select groups was common. A group of friends looking to have a dance might call themselves the Committee of Arrangements or Managers, and they undertook all the same tasks as a planning committee for a public ball. The committee size might range from five to 20 members. If invitations were going out beyond the hosts' local community, it was considered good form to have someone from each town on the committee. And it was also good form, per Daniel Pool's "The Facts of Daily Life in 19th Century England," to RSVP within 24 hours.

Invitations had their own etiquette

For a Victorian ball, invitations themselves were subject to their own rules of etiquette. According to Emily Post's "Etiquette in Society, in Business, in Politics and at Home," There was one way to distinguish a ball from a dance: a ball was open to people of all ages, while a dance was confined to one approximate age range.

Post conceded a certain amount of snobbery in preparing what she dubbed a brilliant ball. Her recommendation for a guest list was to keep it to those whom one would invite to a formal dinner: personal friends and social acquaintances of a certain level of reputation, with very rare exceptions made for co-workers. It was the responsibility of the hostess to make the guest list or to borrow one from a knowledgeable friend or relative if they didn't know enough people.

Invited guests could request additional invitations for any plus-ones they wanted to bring that the hostess didn't know. (If she knew them and didn't invite them, it was a given they weren't wanted.) It was easier to get such approval for young men; they were considered an asset to a ball or dance, while unescorted and unfamiliar young ladies became the responsibility of the hosts. That being said, it was also difficult to refuse without being rude.

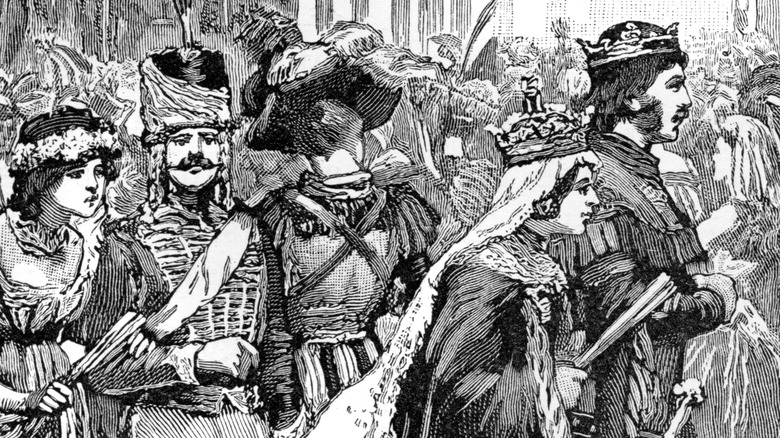

Costume balls let their hosts go all out

A private ball with friends was a good time. A public ball at a respectable venue was a civic function and a show of good culture. But a fancy dress ball with themed costumes was a grand affair at the height of Victorian fashion, and the perfect way for aspiring hostesses to make a name for themselves among the social set. These balls were the talk of newspapers and magazines, not unlike the red carpet premieres of today, and they were a favorite of the aristocracy.

Author and researcher Mimi Matthews assembled a description of the typical fancy dress ball from numerous period articles. Costumes could be dictated by a theme set by the hostess, or they could be up to the guests' imagination and budget. Dressing as one's ancestors would have was always a popular choice, as was going as famous historical figures. A costume ball might go with a Roman theme, or the court of Louis XVI, or venture into what would be politically incorrect territory for today with Turkish or Asian costumes.

A recurring fancy dress ball in Brighton marked the end of the social season, though its prominence faded during a brief dip in the costume ball's popularity in the 1880s. It was fashionable again in time for Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee in 1897, marked by the most famous costume ball of the era in Devonshire House. Before her husband's death, Victoria herself threw several fancy dress balls.

There were dress codes, naturally

One look at a vintage photograph is enough to give away that Victorian society's dress codes were significantly more formal than in modern times. If everyone went about in a suit, tie, and hat for their day-to-day affairs, what must a formal occasion like a ball demand? Victoriana Magazine pieced the answer together from various period sources. As might be expected, dressing for a dance or ball was a complicated and regimented affair.

For women, age, weight, hair, class, and marital status all factored into the cut and color of a ballroom gown. The young and married with an intention to dance would be expected to wear dresses of light fabric, but silk was considered inappropriate except for the married or the non-dancers. Lighter tones were preferable for blondes whereas brunettes tended to wear richer colors. Mourning black was expected for anyone still in bereavement. Flowers and feathers were popular accentuations, but jewelry was expected to be minimal.

Men didn't get any options for the color of their clothes. The coat, pants, and boots were black, and the shirt, gloves, and handkerchief were white (vests and cravats could go either way). It was expected that they would be of the latest fashionable cut. Waistcoats were cut low to show off plaited shirt fronts, but embroidery on shirts and neckwear was frowned upon. Like women, men were expected to keep jewelry to a minimum. And their hair was meant to be well-kept but not too curly.

Men were expected to be on their best behavior

Even in a society that placed a much greater premium on marriage than we do today, unattached guests could often be found in Victorian ballrooms. Observance of the rules of etiquette at such occasions was more than good manners for the unwed; it signaled to others in attendance what sort of prospective match you might make. Myriad rules and protocols governed the behavior of women at dances, but men weren't off the hook from convention either.

From various period sources, author and researcher Mimi Matthews put together a list of principles of etiquette a gentleman could expect to observe at a Victorian ball, starting with an immediate reply to an invitation. The proper dress should be confirmed by a servant or a friend's inspection. When attending a ball hosted by someone else, all the ladies of the household should be greeted on arrival, and if the ball was hosted in the gentleman's household, he was to ensure that all the women had dance partners, even if that meant he had to dance with the old or the ugly.

The rules extended into the dancing itself. Gentlemen did not let their attention wander when they were with a partner, they didn't get carried away by the music or attempt a dance they didn't know, and they didn't attempt intimate whispers or any funny business with their hands during a dance.

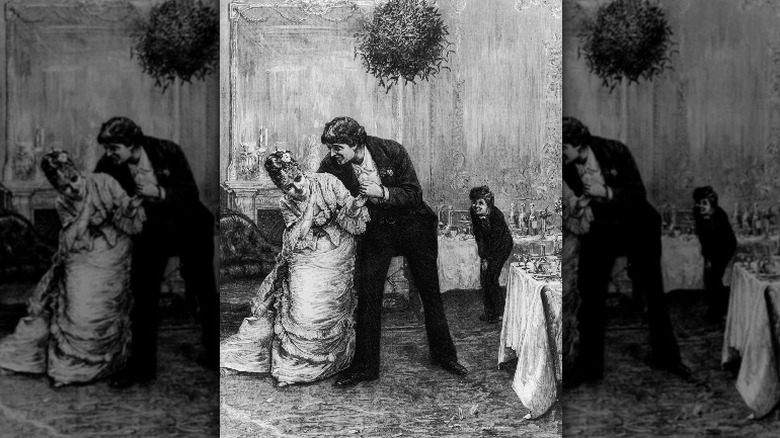

A special holiday ball decoration was ... a ball

On certain festive occasions, the perfect decoration for a Victorian ballroom was a literal ball, one that continues to have an influence on our modern Christmas traditions. The kissing ball, an ornament made of herbs, holly, mistletoe, and evergreen plants, according to the Sheffield Industrial Museums Trust, originated in the Middle Ages. It was commonly accentuated with a figure of the baby Jesus placed inside, and it was hung somewhere in the house where residents and visitors could pass under it and receive good luck from the "holy bough," as it was then known.

In the Victorian era, the balls were built up around an apple base, and flowers and ribbons were more popular decorations than figurines. The balls became seen more as a romantic symbol than one of good fortune. Christmastime ballrooms might have dozens of kissing balls hung up for young couples to meet under. Over the course of the 20th century, kissing balls lost much of their appeal, in ballrooms and households. But one of the plants that went into the ball — mistletoe — lingered on over doorways and from ceilings. It's still to be found at Christmas parties today.

The art of flirtation, as expressed by fan

The idea that Victorian society was repressed and prudish relative to modern times is a common misconception (per History Today), but it was a society that enforced a long list of rules around etiquette. It can be hard to get to know a potential romantic interest when you have to maintain the protocols of polite conversation. But flirtation is often an indirect art, and a popular myth holds that the Victorians had their ways to signal interest (or lack thereof) without flouting convention.

As the National Trust for Scotland explains, Victorian ladies were said to flirt through various signals with the fans that were a staple of ballroom fashion. A clipping from an 1866 edition of Cassell's Magazine provides a key to this fan-flirting language in the Victorian era. To give just a small example: hate was signaled by drawing the fan through the hand while drawing it across the cheek meant love.

If this seems like too much to be true, that's because it probably is. According to Sotheby's, published guides to fan language and the very idea of there being one was less a genuine means of flirtation and more a marketing gimmick to revive fan sales after the French Revolution put them briefly out of fashion. Some women may well have practiced fan language, but odds are that the only people in the ballroom who knew what they were saying had read the same advertisements.

What kind of dancing did the Victorians like?

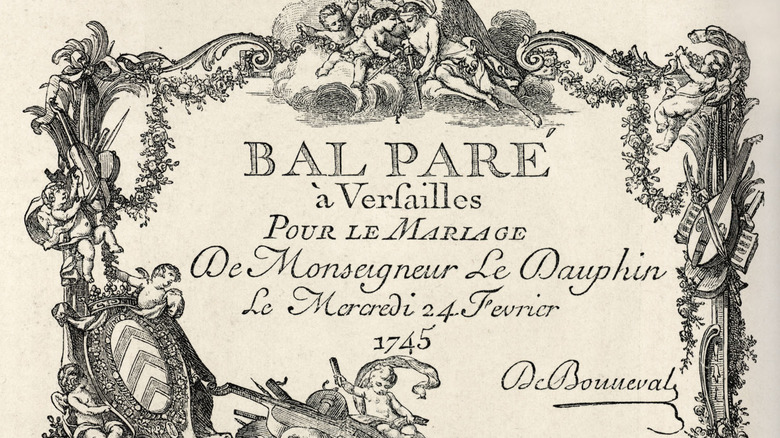

Before the Victorian era, balls and dances favored group steps. Partner dances like the waltz first made an appearance in the ballroom during the Regency era but were infrequently performed and often regarded as scandalous according to dance historian Richard Powers (via Stanford). More popular was the quadrille, a four-couple dance descended from earlier French steps.

Adapting dances from other European cultures was common practice despite intense international relations. The Early Dance Circle explains how the waltz itself grew out of German folk dances interpreted by pre-revolutionary France. As the Victorian age progressed, the waltz became more popular, as did other partner steps like the polka and the mazurka. Group dances retained a presence as well. The support of the royal family helped make Scottish reels a popular feature of balls.

By the end of the period, the beginnings of tango and ragtime had arrived on the dance scene. But the ballroom was no longer the premier dancing destination, according to Powers. Balls were associated with the older generation, and the dances performed were fewer in number and more standardized than they had been at the height of the Victorian era.

Hang on to your dance cards

If you've ever told someone that your dance card was full, you can thank the Victorians for the expression. Of course, for them, it had a more literal meaning. As Emily Post's "Etiquette in Society, in Business, in Politics and at Home" explains, young ladies in attendance at a public ball would keep a dance card with them. On it, they would pencil in the names of whichever gentleman they promised a given dance to, in chronological order and with the type of dance indicated. This put the responsibility of asking for a dance squarely on men's shoulders, and while it was considered rude to decline a request to dance if one had an open slot, once a dance card was full, a woman was under no obligation to go into overtime.

The cards themselves could be simple pieces of paper or more elaborate creations worked into a woman's costume for the evening. Museu da Moda Brasileira noted examples of illustrations, musical instrument shapes, or converting one's fan into a dance card. Curiously, Post reports with some displeasure that dance cards were popular for public balls, but not private ones. She guessed that the social set didn't like working on a schedule when at home. In any event, the practice of using dance cards didn't long survive the Victorian era; they were out by the 20th century.