The Tragic Story Of The Wrightsville 21

In March 1959, 21 African-American teenage boys — known as the Wrightsville 21 — tragically died in a mysterious fire in Arkansas. Decades after the harrowing event, a monument was erected to honor the boys' memories. At that time, a spokesman from the Arkansas Department of Correction, Solomon Graved, was quoted as saying that what happened was "a tragedy that, if we're honest with ourselves, should never have happened," (via the Arkansas Democrat Gazette). What led to the catastrophe that took the lives of the boys, and who was responsible for it?

The Arkansas Negro Boys' Industrial School (NBIS) — a juvenile correctional facility — was established in 1923, and by the late 1930s, it had two locations: one in Wrightsville and another in Pine Bluff. According to the book "The Pioneers" by Bettye J. Williams, NBIS housed Black youth with minor offenses, but there were also some orphans who were sent to the facility. Prior to the establishment of the juvenile center, Black youth offenders were sent to the Adult Black Penitentiary. Those in NBIS were sentenced to farm work, and the conditions weren't ideal. They went for days without bathing or changing clothes, there was a lack of basic facilities, and they were punished by whipping for infractions they committed.

The mysterious fire of 1959

The Wrightsville location of NBIS typically housed as many as a hundred teenagers, and they lived in cramped dorms at the Works Progress Administration building. It was a far cry from the facilities at trade schools for white youth that offered lessons for various vocations. The building was deteriorating, and many parts of the facility were in need of repairs. In 1959, NBIS Wrightsville had 69 boys aged 14 to 17 years old. According to the Equal Justice Initiative, many of the juveniles had the most minor "offenses," examples of which include soaping windows as a Halloween prank or riding a white boy's bike (even with permission from the bike owner).

At 4 a.m. on March 5, 1959, a mysterious fire engulfed the dorm building where the 69 boys slept. NBIS staff were away for the night, and the dorm was locked from the outside as was typically done every night. The boys awoke to clouds of smoke and fire that quickly ravaged their quarters (per Encyclopedia of Arkansas). Some boys managed to break two small windows, and they scrambled their way out. Others weren't so lucky. Out of the 69 boys, 21 weren't able to escape, and they burned to death.

The burial of the Wrightsville 21

Out of the 21 boys who died in the fire, only seven were privately buried by their families. The 14 other boys were buried together in a mass grave at the Haven of Rest Cemetery that was paid for by the state. According to the Arkansas Times, their bodies were so badly burned that identification was difficult. The bodies were discovered all huddled in the corner of the dorm room that was farthest from the door. There were two exits, but both were locked.

Many of the family members believe that the fire was no accident. In 2017, Frank Lawrence, whose 15-year-old brother Lindsey Cross died in the blaze, said, "It was a carefully calculated murder that involved 21 boys but was designed to kill 69 that were housed inside of this dormitory" (via KATV). Normally, there were NBIS staff present, but during that night, all three who had access to the dorm keys were not around for one reason or another. NBIS employees were interviewed, and their statements regarding the locked doors and about how they discovered the fire varied.

Who was to blame for the fire?

Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus, who supported segregation, ordered an investigation. However, as noted by The Journeyman, authorities did not follow standard procedures and neglected to preserve the scene. The Little Rock Fire Department suspected that the blaze started in the attic of the caretaker's room, which was located near the main entrance of the boys' dorm building. The fire chief told The New York Times that faulty electrical wiring most likely started the fire.

Just a year prior to the fire, Governor Faubus visited the facility and saw firsthand the squalid conditions and said, "They really need help." Instead of addressing the issue, however, Faubus never recommended changes to be made and even lessened the juvenile center's budget by $7,100, as reported by the Northwest Arkansas Democrat Gazette. Faubus gained notoriety in 1957 as the politician who prevented nine Black students — known as the Little Rock Nine — from attending an all-white school in Little Rock by calling the National Guard. He claimed it was for their own protection. After the fire, letters from all over the U.S. and even from other countries were sent to Faubus. One person from Detroit wrote, "You are just as responsible as if you had struck the match." Another said, "It sure must have made you happy to have those boys roasted alive."

The investigation's findings

Governor Orval Faubus put the blame on NBIS' superintendent, an African-American man named Lester Gaines. Faubus stated that Gaines neglected to ensure the boys' safety on that fateful night (via Encyclopedia of Arkansas). A grand jury determined that there were several departments and individuals who were responsible for the death of the Wrightsville 21 including the board of directors, the superintendent, the state administration, and the general assembly of Arkansas, as noted by Liberty Writers Global. Despite the findings, however, no one was indicted.

Arkansas reportedly gave about $3,300 and $5,900 to each of the boys' families for damages, but according to The Journeyman, some white attorneys who represented the families took as much as half of the amount for compensation. Luvenia Lawrence, whose son died in the fire, said her family was awarded $3,400, but she was only given $1,000 by a man who visited her home one day. She brought the check to a pawn shop where the owner asked her, "Is this all Faubus gave you for killing your son?" (via the Arkansas Times).

The Wrightsville 21 remembered

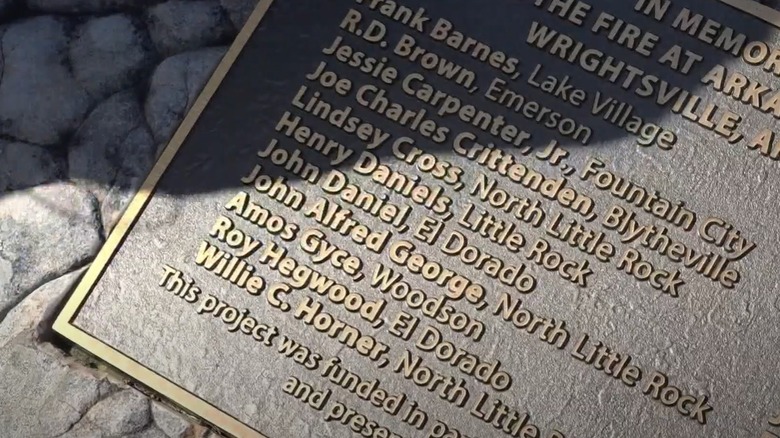

For decades, the mass grave at the Haven of Rest Cemetery was left unmarked. It wasn't until 2018 that a plaque that contained a list of the 21 boys' names who died was placed on the gravesite, thanks to the efforts of family members, donations, and a grant from the Curtis Sykes Memorial Fund, as reported by the Arkansas Times. History professor Dr. Brian Mitchell stated, "If you look honestly at the situation the conclusion we come to is that these boys died of racism, the same racism we live with today."

Today, the site where NBIS once stood in Wrightsville is the location of the Arkansas Department of Correction. In 2019, a dedication ceremony was held to honor the memory of the 21 boys who died in the fire, and a marker was erected. Maedean Horner, whose brother, Willie Horner, died in the fire, said, "This is kind of like a closure to a funeral that should have happened 60 years ago" (via Arkansas Democrat Gazette).