Who Is Moriarty From The Sherlock Holmes Stories? Your Guide To The Character.

It's almost a prerequisite these days for a fictional character described as a superhero to have an archnemesis, one nefarious opponent to stand head and shoulders above the rest. Batman has the Joker, Superman has Lex Luthor, and James Bond has Ernst Stavro Blofeld. Even before the modern age and what we would think of as superhero fiction, the dynamic popped up; just look at Robin Hood and the Sheriff of Nottingham.

But what of a more immediate predecessor to today's costumed crime fighters, that super sleuth of Victorian England: Sherlock Holmes? The world's greatest detective and his partner, Dr. John Watson, are more famous than any of their opponents. The Hound of the Baskervilles got its name onto one of the Holmes novels, but by and large, it's been Holmes himself and his methods of deduction that have made their mark on pop culture, not his clashes with any particular villain.

But even Sherlock Holmes has an archnemesis. His appearances within the original canon are few, but his legacy has been considerable. Holmes himself dubbed him the Napoleon of crime, named him the mastermind behind numerous capers, and nearly lost his life in the battle to bring him down. Pastiche, revisionist, and derivative Holmes tales have built him up ever since (per the Sir Arthur Conan Doyle Literary Estate). He is Professor James Moriarty, and here is a guide to his nefarious character.

Professor of mathematics and the Napoleon of crime

Professor James Moriarty made his first and only direct appearance in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's original Sherlock Holmes stories with "The Final Problem," published in The Strand in December 1893 according to Daniel Stashower's "Teller of Tales: The Life of Arthur Conan Doyle." In describing their archnemesis to Dr. Watson, Holmes pulls no punches. "He is the Napoleon of Crime, Watson," he says in "The Final Problem" (via McClure's Magazine). "He is the organizer of half that is evil, and of nearly all that is undetected, in this great city [London]."

This dangerous mind rests in an unassuming frame. Doyle paints Moriarty as a thin chap, clean-shaven and pale, with sunken eyes, a bald head, stooped shoulders, and a habit of slowly moving his head from side to side like a reptile. Polite society knows him as a well-bred genius of mathematics and a respectable, retired professor of the subject. It's only Holmes, through various and seemingly unrelated cases, who realizes that Moriarty has become a singular brain trust to a wide network of criminals, offering direction, strategy, and protection for loyalty and riches.

Moriarty realizes that Holmes is onto him and confronts him with an ultimatum in "The Final Problem": back off the case or die. "If you are clever enough to bring destruction upon me," he tells Holmes, "rest assured that I will do as much to you."

Involved in two stories, mentioned in five

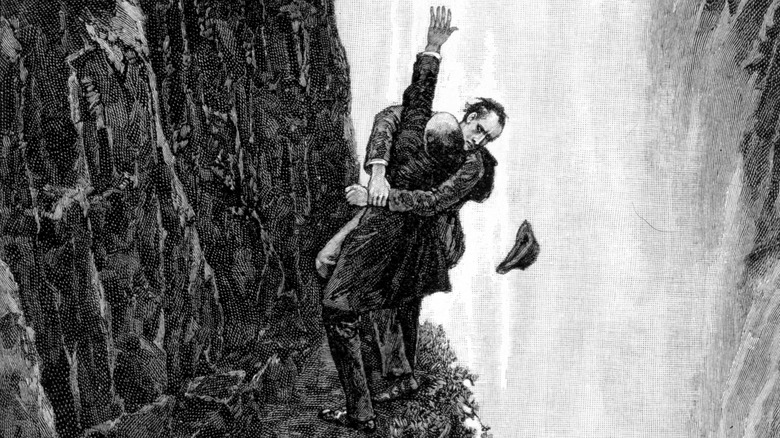

For all the infamy he has achieved, Professor Moriarty only directly appeared in one Sherlock Holmes story, "The Final Problem." Per the Sir Arthur Conan Doyle Literary Estate, he plays an unseen role in the Holmes novel "The Valley of Fear," written after "The Final Problem" but set before it. In "The Valley of Fear," Holmes first becomes aware of Moriarty's criminal activity, and it ends with a premonition of "The Final Problem," where Holmes and Moriarty seemingly kill one another (via Camden House).

Holmes would return for many more adventures, while Moriarty remained crushed and drowned at the bottom of a waterfall. But Doyle mentioned him in five more short stories. "The Adventure of the Empty House” (via Camden House), responsible as it was for explaining how Holmes could return from the grave, necessarily detailed their battle at Reichenbach Falls and Holmes' manner of escape. The case investigated within the story also concerned the last remnants of Moriarty's organization.

After "The Empty House," mentions of Moriarty were brief and often colored by a curious regret on Holmes' part that his nemesis was no longer around. He complains of how boring London is without Moriarty's crimes to solve at the beginning of "The Norwood Builder" (via Camden), names a possible heir to Moriarty's genius in "The Missing Three-Quarter" (via Camden), dismisses another such claim in "The Illustrious Client" (via Camden), and names a favorite song of the professor's in "His Last Bow" (via Camden).

He may have been inspired by the real-life Napoleon of crime

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle had a considerable way with words, but he did not coin the phrase "Napoleon of crime." He only appropriated it for Professor Moriarty, as detailed in "Teller of Tales: The Life of Arthur Conan Doyle." The description was invented by Robert Anderson, detective of Scotland Yard, in reference to a real-life thief who just may have been Doyle's model for the good professor.

Adam Worth was an American safecracker extraordinaire, who ran afoul of investigators in his home base of New York City in the 1860s (per Smithsonian Magazine). He fled to England under the name Henry J. Raymond and passed himself off as a gentleman. This was a façade he kept up for years, all the while sitting at the head of an international criminal organization that confounded police from London to Port Elizabeth, South Africa. Among his treasured spoils of crime was a famed portrait by Thomas Gainsborough of Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire.

Anderson eventually dubbed Worth the Napoleon of crime on account of his height, according to Ben Macintyre's "The Napoleon of Crime: The Life and Times of Adam Worth, the Real Moriarty," and Macintyre accused Worth of developing a Napoleonic complex. He was finally caught in an ill-conceived daytime robbery in Belgium, where he spent five years behind bars and lost his wife and fortune. But in his final years, Worth found friendship with none other than William Pinkerton, whose detective agency had hunted after Worth for decades.

He's got a henchman

Can you truly call yourself an archnemesis to a superhero if you don't have a henchman to do your dirty work? Professor Moriarty has no named accomplices when he confronts Sherlock Holmes in "The Final Problem," but his entire operation depended on criminals seeking his counsel and carrying out his dirty work. After the professor's death, one of these operators stepped up to exact revenge.

That man was Colonel Sebastian Moran, and according to the Conan Doyle Estate, he was Moriarty's chief of staff. Holmes dubs him the second-most dangerous man in London after his boss. A former officer, hunter, and adventurer in British India, Moran fell into criminality there and was forced to retire from the army. On his return to London, he fell in with Moriarty and partook in the professor's attempt on Holmes' life in Switzerland. It was partly to avoid Moran that Holmes faked his death for three years.

Moran's undoing comes in "The Adventure of the Empty House." He uses an air gun, once intended by Moriarty to kill Holmes, on a rival card player, alerting Holmes to his presence. Holmes returns to London and baits Moran with a dummy to shoot with the air gun. The trap works, Moran is apprehended, and as of "The Illustrious Client," he still lives in prison. Holmes mentions him in the same breath as his one-time boss Moriarty as them being true terrors, when dismissing the potential menace of another criminal.

Was he only created to kill off Sherlock Holmes?

One of the appeals of archnemeses is their recurring nature — Batman has been battling the Joker for decades. Professor Moriarty stands out from the pack in that he does not keep coming back in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes stories: He's there for "The Final Problem" and influences from the shadows in "The Valley of Fear," no more. If Doyle were to have had his way, the latter story would never have been written — indeed, no Holmes tale after "The Final Problem" would have.

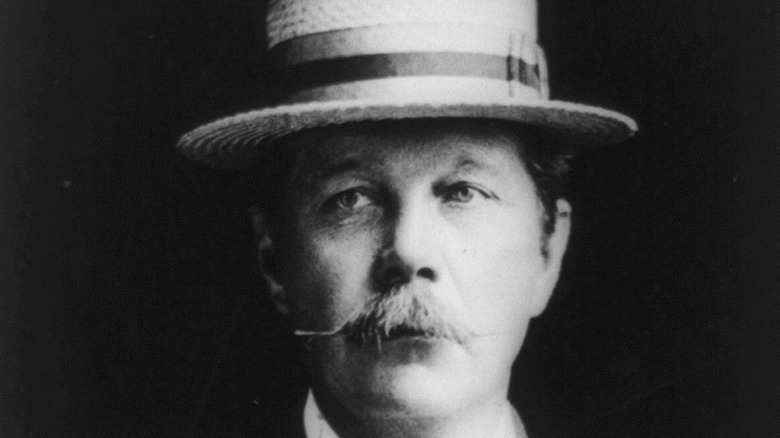

Per Daniel Stashower's "Teller of Tales: The Life of Arthur Conan Doyle," after two series of Holmes stories, Doyle was sick of his creation. Despite the public's adoration of Holmes, Doyle considered his adventures only a modest literary accomplishment, and he began feeling pigeonholed as a writer only of Sherlock Holmes. He told friends and peers that if he didn't finish off Holmes, Holmes would finish off him. But if he was going to kill his hero, Doyle wanted to do it in a suitably exciting fashion.

After taking in the Reichenbach Falls during a visit to Switzerland, Doyle felt he had an appropriate location for a final stand. Back in London, he created Moriarty as a criminal of such cunning and destructive potential, that Holmes himself declares that the capture or death of Moriarty must put the cap on his career as a detective. Then Doyle sent them over the falls together, convinced that was the end.

Anti-Irish or harbinger of death?

Moriarty is an Irish surname. So is Moran, that of Professor Moriarty's chief henchman. Many of the villains in the fourth Sherlock Holmes novel, "The Valley of Fear," are Irish-American. The prevalence of Irish characters on the wrong side of the law led author and critic Michael Walsh to write (via the Conan Doyle Estate) about possible anti-Irish sentiment within the Holmes canon.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was of Irish descent himself, on both sides: Doyle is an Irish surname, and his mother, Elmore Welden, was an Irishwoman, according to Daniel Stashower's "Teller of Tales: The Life of Arthur Conan Doyle." But Doyle was born in Scotland, considered himself British, and was a full-throated supporter of the British Empire. As the status of Ireland within the empire became more contentious, Doyle stood for Parliament on two occasions as a Unionist. But in the 1910s, he admitted in private letters (via The Guardian) that he had grown more sympathetic to the idea of Irish home rule.

Of course, the villain names could be a coincidence. Or there may have been another reason for Moriarty's name, as Walsh conceded in his essay. Moriarty and Moran share the prefix "mor," as does Mary Morstan, the wife of Dr. Watson. The prefix is close to the Latin "mort," meaning death, and death is associated with all three characters. Moriarty and Morstan die over the course of the Holmes stories, and Moriarty and Moran are agents of death.

Moriarty inspired a T. S. Eliot cat

Sherlock Holmes has had a long and varied influence on later characters in popular fiction, such as the curmudgeonly doctor Gregory House (per The Seattle Times). Michael Walsh suggested (via the Conan Doyle Estate) that the villainous Professor Moriarty had his own progeny in the person of Ernst Stavro Blofeld, James Bond's archnemesis. However, one confirmed descendant of Moriarty's was significantly less threatening to the world at large.

T. S. Eliot was a prolific writer whose work covered a wide range of subjects. His collection of light verse, "Old Possum's Book of Practical Cats," has endured as child-friendly poetry and the subject of Andrew Lloyd Webber's hit musical "Cats" (per the British Library). Among the most popular of the colorful cats described in the collection is Macavity the Mystery Cat, alias the Hidden Paw. This thieving and deceiving feline befuddles the authorities, leaves behind no trace of his guilt, and controls the operations of other criminal cats. The poem's end declares him the Napoleon of crime — Moriarty's own appellation.

The shared description was not a coincidence. Eliot was a big fan of the Holmes stories and deliberately patterned his own master criminal on Arthur Conan Doyle's. In a letter to a friend (via the blog of Dean Sarah Bey-Cheng of York University), the poet happily named Moriarty as the model for Macavity, while lamenting that his poem wasn't as successful with his godchildren as his other cats.

He received a tribute from New Scientist

Fans of Sherlock Holmes have sometimes taken to engaging in what scholar Leslie S. Klinger calls (via an interview with Author Link) a gentle fiction: that the great detective really did live, Dr. Watson really did chronicle his adventures, and a genuine timeline of their lives and careers can be worked out. Klinger played this game with his annotated edition of the Holmes canon, and other authors and filmmakers have produced works purporting to tell of the "real" Holmes and Watson behind the stories. But of all the people to indulge in this gentle fiction, the most unlikely may be a mathematician.

John F. Bowers was in the School of Mathematics at the University of Leeds in 1989, when he decided to have a bit of fun with Holmes' archfoe, Professor Moriarty. Adopting the gentle fiction described later by Klinger, he assumed that Moriarty was a genuine mathematical genius who produced immeasurable contributions to the field — and a criminal reputation — that time had unfairly buried.

Bowers put this fanciful idea to pen, not in the pages of a fiction magazine, but in New Scientist, which published the fictional reappraisal in December 1989. Moriarty's work is therein described as revolutionary, and his supposed volume "The Dynamics of an Asteroid" a masterpiece of great value to astronomers. The article recasts Holmes as not only mistaken about Moriarty's criminal activity, but guilty of the professor's murder.

How many brothers did he have?

Professor Moriarty was not alone in his criminal activities. He had his chief lieutenant, Colonel Moran, and his operation consisted of career crooks turning to him for direction and protection. But what of his private life? Moriarty's reputation outside the criminal world was that of an ascetic, retired mathematician, and Sherlock Holmes discusses no family for his archnemesis in "The Final Problem" (via Camden House). But Dr. Watson mentions a brother at the beginning of that story, a Colonel James Moriarty, who is attempting to defend his sibling's reputation.

Curiously, when Holmes returns in "The Adventure of the Empty House” (via Camden House), he gives Professor Moriarty a given name — and it is also James. And in the Holmes novel "The Valley of Fear," set before "The Final Problem," Holmes describes Moriarty as having a brother who works as a station master in west England (via Camden House). Is this the same James with the rank of colonel, who went on to defend his criminal mastermind brother in the press, or a third Moriarty?

Author Vincent Starrett has fun exploring Moriarty's family tree in "221B: Studies in Sherlock Holmes." While no definitive answer is forthcoming from the long-deceased Arthur Conan Doyle, Starrett's favored conclusion is that there were indeed three Moriarty brothers — and they all had the same name. With the amount of confusion this must have caused while growing up, perhaps it's small wonder that one of the Jameses developed antisocial tendencies.

Was he really that bad?

Could Sherlock Holmes have been wrong about Professor Moriarty and his criminal organization? The great detective was mistaken on several occasions, as Scientific American describes. But the idea that he could have pinned a shadowy network of thieves and murderers on the wrong man — or invented the gang altogether — is never entertained in the original Holmes canon.

That hasn't stopped later writers from producing continuations, revisionist tellings, feigned histories, and works of pastiche, wherein Holmes might very well have misjudged the good professor. Among these writings is Nicholas Meyers' novel "The Seven-Per-Cent Solution," first published in 1974 and adapted into a film two years later (per The New York Times). The premise of the story is that Holmes' battle with Moriarty, his supposed death, and his return three years later were a fiction designed to paper over Holmes' recovery from his cocaine addiction.

A consequence of his drug use was Holmes' delusion that Moriarty, recast here as Holmes' childhood math tutor in addition to an eminent professor, is a villain. In disguised hypnotherapy sessions with none other than Sigmund Freud, it's discovered that Moriarty brought young Holmes the news that his father had killed his mother for adultery. In a drug-addled state, Holmes' childhood resentment at his tutor being the messenger manifested as seeing Moriarty as an arch-criminal.