Thor Heyerdahl's Ocean Treks Were Even More Impressive Than You Thought

In the early 20th century, Norwegian academic and adventurer Thor Heyerdahl mounted four of the most daring sailing expeditions of all time, all in the name of experimental archaeology. Heyerdahl had a hunch — a hunch that became an obsession — that ancient people were not as isolated from each other as previously believed, and that many people may have successfully sailed between continents well before Columbus or Leif Erikson were even born (via All That's Interesting).

Conventional wisdom ran that ancient seafaring technology was not capable of constructing a vessel that could survive a perilous trip across the Atlantic or the Pacific, but odd similarities between certain cultures bothered Heyerdahl (via History). Was it just a coincidence that both the Egyptians and the inhabitants of ancient Mexico were pyramid builders? And how did plants from the Americas end up in Polynesia?

Heyerdahl is perhaps best known for his argument that the islands of Polynesia were partially colonized by people from the Americas, a conviction that led to his most famous expedition: the Kon-Tiki voyage (via the Kon-Tiki Museum). This trip was inspired by a Peruvian legend about Kon-Tiki, an Incan God who supposedly sailed west across the ocean on a balsa wood raft. By eerie coincidence, the Polynesians have their own myth about a certain chieftain called Tiki, a visitor from a heavenly land (via Smithsonian Magazine). Putting two and two together, Heyerdahl concluded the story may have had a basis in fact, and set off on his journey.

Kon-Tiki

Attempting to copy the journey of the Peruvian god, Heyerdahl built a balsa wood raft held together with simple hemp ropes (via All That's Interesting). Heyerdahl came up with a theory that natural ocean currents that move West across the Pacific could have taken sailors to Polynesia by accident.

To test his theory without cheating, he made a raft that was couldn't be steered, hoping to rely on the same drift patterns (via Smithsonian Magazine). None of the group could sail anyway, so it hardly mattered (via Kon-Tiki Museum). The group had to withstand several Pacific storms while at sea (via The National), and to make matters more dangerous, Heyerdahl himself was a poor swimmer who hated the water, having almost drowned as a child (via Smithsonian Magazine).

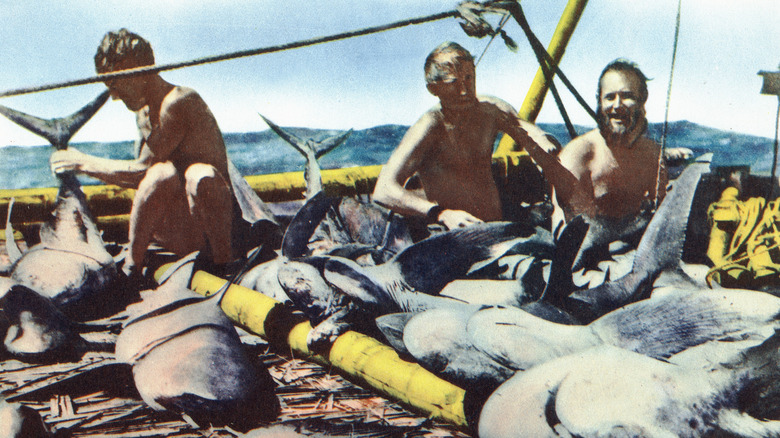

Relying on rations as well as fishing, the group had plenty to eat on the way there, but they were also in constant danger of being eaten, as sharks followed their raft while they sailed. Unbothered by the danger, the group baited the sharks for fun. Although one crew member, Herman Watzinger, nearly drowned on the way there, the group traveled all the way to Polynesia unscathed. Only the group's pet parrot didn't make it, vanishing in a storm mid-journey. Crossing 3,700 nautical miles over the course of 101 days, the crew washed up on the shores of French Polynesia.

Sail like an Egyptian

Heyerdahl's next trip was even more ambitious. Constructing a papyrus boat in Egypt, and naming it after the sun god Ra, Heyerdahl attempted to cross the Atlantic from a port in Morocco (via the Kon-Tiki Museum). Depictions of reed boats appear in both South America and Egypt, making it the obvious choice of construction material for an archaeological experiment (via The New York Times). This time the crew also took ducks, chickens, and a pet monkey along for company (via UNESCO).

Heyerdahl's second daring voyage would ultimately fail, although only just. The crew sailed roughly 2,700 nautical miles across the Atlantic Ocean before the dense reeds became waterlogged and began to fall apart. Forced to use their polystyrene life raft to secure the back of the boat and keep themselves afloat, the group sent out a desperate SOS signal. The trip finally ended under grim conditions; after the group finally got a rescue response, they prematurely threw their food and water overboard, and spent another five agonizing days at sea without supplies.

Despite the disaster of the Ra voyage, Heyerdahl tried again with Ra II, this time hiring a group of expert craftsmen from Peru to make another reed vessel. The second voyage did make it all the way to Barbados, once again using only ocean currents. Heyerdahl made a final 143-day voyage down the Tigris River in 1977, definitively proving that ancient sailors were capable of making such long journeys (via the Kon-Tiki Museum).