The Obsession With True Crime Is A Lot Older Than You Think

It was back in 2015 that major culture outlets such as The Guardian announced that the true crime genre was in the midst of a major boom. Interest in the topic ranged across media, including books, TV, and podcasts going through the roof thanks to then-groundbreaking new releases such as "Serial" and "The Jynx," which have since gone down in history as true crime classics.

But the true crime boom has shown no sign of slowing in the years that followed, with high-profile shows chronicling the lives of serial killers such as Jeffrey Dahmer as well as the misdeeds of high-profile con artists and fraudsters. Modern audiences' thirst for true crime has raised many questions among social commentators, journalists, and academics, who ask why exactly people today are so attracted to real-life tales of violent death and fraud. Is there something about the way we live our lives today that leads us to collectively develop a curious fascination with the darkest parts of the human soul?

It turns out that though the modern true crime boom really got going in the mid-2010s, audiences' perverse interest in the most sinister and shocking events is a very long tradition. It seems that humanity has probably always had a keen interest in true crime.

The 'broadside'

When delving into the history of true crime, many commentators look to Victorian Britain, a notoriously closeted but perversely curious society in which an overriding fear of murder — especially on the streets of dark and smoggy Victorian cities such as London and Manchester — transmuted into a grim fascination with real-world crime in all its brutality. As The History Press notes, famous crimes such as the story of Jack the Ripper, a serial killer who preyed on vulnerable London sex workers, were a sensation in their time and, as they remain unsolved, continue through books, documentaries, and scripted dramas today.

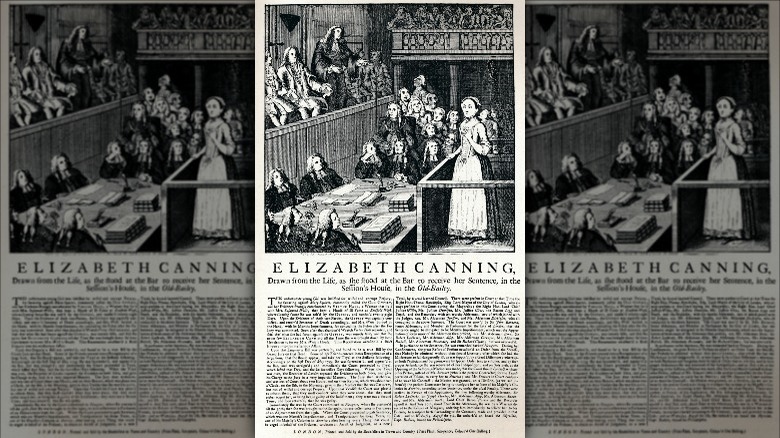

But the British taste for tales of true crimes goes back further than the 1800s. As Pamela Burger notes in a blog article published on JSTOR Daily, modern fascination with true crime can be traced back to the 16th century, which saw the publication of the first "broadsides" — printed pamphlets that reported local crimes in horrifying detail, accompanied by woodcut illustrations of the crime scenes, alongside ballad songs telling the tales of legendary crimes and articles outlining the results of trials. These broadsides were soon popular among the literate middle class up until the Victorian era.

Murder as art?

One Briton who had a pivotal influence on the true crime tastes of his own country was Thomas De Quincey (1785-1859) (above). He was a writer who is best remembered for his controversial 1821 memoir "Confessions of an English Opium Eater."

Per The New Republic, De Quincey was interested in the moment that audiences delve into the minds of murderers and, somewhat shockingly, come to identify with them as they would a traditional fictional hero. Beginning his writing on murder with an essay titled "On the Knocking on the Gate in Macbeth," De Quincey noted that theater audiences of William Shakespeare's 1606 play can't help but lend their allegiance to the murderous title character when he is at risk of being caught. In doing so, De Quincey explained the draw of true crime among modern audiences too — rather than simply recoiling at the fate of the victim, murder rendered in art effectively "throw[s] the interest on the murderer," too.

But De Quincey's biggest contribution to the true crime genre came in his famous satirical essay series "On Murder Considered as one of the Fine Arts," which, using a series of 1811 London killings as its foundation, offers a defense of the "aesthetic" appreciation of murder — as modern true crime might be described as doing — as, in the case of murder, it is already too late prevent the crime, and therefore to appreciate and find entertainment in the gruesome details of the story is potentially justified. It must be noted, however, that De Quincey's tongue was very much in his cheek in the writing of these essays.

Zhang Yingyu's 'The Book of Swindles'

But it isn't just western audiences who have found true crime to be a copious source of perverse entertainment. In Ming Dynasty China, where crime and courtroom fiction were all the rage, one volume says this better than most: "The Book of Swindles," published by author Zhang Yingyu in 1617.

As noted by Columbia University Press, Zhang's book was released during a time of bustling mercantile expansion in China, and while this new wealthy middle class was enjoying great wealth, it also meant that they were ripe targets for con artists, thieves, and tricksters looking to separate them from their new money. The volume, then, offers dozens of individual crime stories that seek to educate readers about contemporary fraud tactics, but also read as titillating true crime tales at the same time.

Though modern readers typically approach Zhang's most famous work as a collection of short fiction, the Association for Asian Studies notes that stories shared therein were at least only "semi-fictional." It was a compilation of rumors the author had heard on his travels of seemingly real-world crimes, and he believed his contemporary travelers — many of whom were a new generation of traveling businesspeople — should be aware of them. As with modern true crime, many turned to Zhang's work for instruction on how to avoid becoming unwitting victims of swindles themselves.

True crime in the 20th century

True crime also gained a wide audience in the early years of the 20th century. That's when Edmund Pearson, a former librarian, made a career as a best-selling crime writer by specializing in literary investigations into famous murder cases.

According to the Library of America, Pearson once declared, "Eight out of 10 people are interested in murder ... and of the two, one is a pretender." And based on his success as a writer, starting with the publication of "Studies in Murder" in 1924, he wasn't wrong. The collection of investigations famously held Pearson's findings with regard to the infamous Lizzie Borden murders, with the former librarian declaring that the accused murderess (pictured) — who was acquitted of all charges in 1893 — was indeed the culprit. Like modern true crime phenomena like "Making a Murderer" and "The Jynx," "Studies in Murder" titillated its audience with seemingly insightful reportage that got under the skin of the official story as found in typical, frustratingly scant news reports.

By the mid-century, a new generation of writers were turning to true crime as a source of literary inspiration. Truman Capote, best known for his classic 1958 novella "Breakfast at Tiffany's," pioneered the "true crime novel" genre in 1965 with the release of "In Cold Blood." The "non-fiction novel" in question offers a retelling of the 1959 murders of the Clutter family of Holcomb, Kansas, a shocking tale that Capote obsessively researched for his book, which outlets such as The Daily Beast describe as his "masterpiece."

True crime: always booming

Capote's bestselling "In Cold Blood" led the way for stylized retellings of real-world violence in the second half of the 20th century, heavily influencing other hugely successful true crime releases, such as Vincent Bugliosi's breathtaking 1974 account of the Charles Manson murders, "Helter Skelter." So far, Bugliosi is the only true crime writer to outsell Capote (via The Daily Beast).

In 1991, the critic and scholar Jack Miles published a paper titled "Imagining Mayhem: Fictional Violence vs. 'True Crime'," (via The North American Review), in which he explores the appetite for entertainment featuring real life crimes, from the turn of the 20th century onward. He notes that at that year's American Booksellers Association convention, three deals were brokered between publishers and authors to release books detailing the same San Francisco murder, and writes that, looking back through the centuries to Shakespeare — just as Thomas De Quincey had done — audiences have always been "bloody-minded." It seems that the current taste for true crime is less of a boom than a continuation of how things have been for a very long time.