The Difference Between Wicca And Witchcraft Explained

Witchcraft and witches have long been staples of popular culture and for good reason since the concepts are viewed in several, powerful ways. To many, the words can spark feelings of awe and wonder from childhood experiences, especially after the rise of the hit series, "Harry Potter." Somewhat along those lines, yet in a different way, a growing number of people view most witches in a positive light. As persecuted scapegoats, witches were unjustly punished for performing magic without any malicious intent. In the feminist movement, these ancient and medieval women can be seen as martyrs who stood against the repressive patriarchy.

To the other extreme, witchcraft remains demonized as a classic subject for horror fiction, from film to novels and video games. Even more terrifyingly, the practice is still associated with heinous crimes in some parts of the developing world, same as it was in the ancient past.

Another term sometimes used interchangeably with witches and witchcraft is Wicca, which can be rather confusing. But while Wicca and witchcraft are certainly related, the two are, in fact, quite separate concepts. Though just seeing Wicca spelled out with a capital "W" might give a hint to that difference in that it is slightly more specific, or special, than witchcraft in general — a word that can represent so many different things to different people. So, let's take a deeper dive and explore what Wicca and witchcraft truly mean, both in the present and distant past.

A religion vs. the practice of magic

The main way to differentiate Wicca and witchcraft is to understand that the first is a specific religion or spirituality followed by individuals who perform magic. On the other hand, witchcraft refers to the act itself, which can be done by witches or any other type of spellcaster, as Diane Smith explains in her book, "Wicca and Witchcraft For Dummies." A simple analogy would be to compare the two with Christianity and an action like praying. Just as Christians pray as an essential part of their faith, Wiccans perform various magic rituals in their worship that are all categorized as witchcraft.

Even though Wicca may be lacking the established hierarchy and thoroughly defined guidelines of many major organized religions, it is still officially regarded as such by the United States government (per Justia). And no act within the faith is more important to its adherents than performing their beloved rituals of witchcraft to honor the goddess, life, or any other deities.

Wicca is a modern concept

Whether you consider them accurate descriptions of people's actions or not, accounts of individuals performing witchcraft exist in nearly every corner of the globe and date back to the earliest written records. Although Wicca may incorporate what some consider aspects of this ancient activity, the religion itself has a far more recent origin.

Wiccans may believe their religion is a continuation of pagan beliefs that thrived back all the way to prehistoric times, yet it is more accurate to trace their roots to England in the 1940s. According to Stephen Hayes in his article in Missonalia, two writers specifically, Gerald Gardner and Egyptologist Margaret Murray, covered witchcraft extensively during this period, and their work laid the foundation of what would transform into Wicca (via Nurelweb).

Overall, Wicca is just one of several modern religions that claim to be connected to thousands of years of history and traditions in a movement called Neo-Paganism. In as early as the 19th century, these revival religions slowly emerged, most notably the Druids, per Britannica. There was then an explosion in popularity among Neo-Pagan groups in the latter half of the 20th century, including the Egyptian Church of the Eternal Source, the Norse Viking Brotherhood, the Greek Feraferia, and the Church of All Worlds, the largest of them all. Like Wicca, these religions incorporate witchcraft or ritual magic in their practices, yet in their own unique ways supposedly dating back to ancient traditions.

Wiccans do not cause harm to others

Historically, witchcraft was a concept used by ancient cultures, like the Roman Empire and the Germanic tribes, to describe an attack on people or property deliberately meant to cause damage or injury but was not fully understood, says author Stephen Hayes (via Nurelweb). A prime example of this would have been murder by way of poison, which was often closely tied to the supernatural, according to Diana Paton in journal The William and Mary Quarterly. Since knowledge of sciences like biology and chemistry was so limited, people could barely grasp the true cause for the volatile reactions of toxic substances. Therefore, poisoning was associated with witchcraft to such an extent that the Latin term, "veneficium," was used to describe both.

The intentions of modern Wiccans are the exact opposite of the ancient crimes of witchcraft, as a central tenet of their beliefs is that harm should never be committed on others. Wicca may not have set practices amongst its followers, nor do they all believe in spirituality the same way, yet there are principles they all share, known as the Wiccan Rede and the Threefold Law. Author Diane Smith describes in "Wicca and Witchcraft For Dummies" the meaning of the Rede, which is essentially to follow your own heart as long as you cause no harm to other living beings in the process. Furthermore, the goddess exists in all life, according to Wiccans, so any attack on a living creature is the same as one on the revered deity. In addition the Threefold Law explains the consequences of any actions in that what ever a person sends out comes back to them three times as much.

Some followers adhere to these tenets so strongly that they refuse to be called witches in order to avoid any association with the darker side of magic.

Not all witches identify as Wiccans

In the U.S. where Wicca has the largest following, more witches are devoted to that faith than any of the other religions based in witchcraft. But that does not mean all witches in the North American country are Wiccans. According to The Conversation, there are approximately 1.5 million witches nationwide, and there are only 800,000 people who identify themselves as Wiccans. Out of the witches who are not Wiccans, a good amount of them do not even have any association with paganism as well, says The Atlantic.

On the other end of the spectrum, Diane Smith points out in "Wicca and Witchcraft for Dummies," how there are also a decent number of Wiccans who do not call themselves witches and consider the religion something else entirely different. To them, Wiccans follow a separate spiritual faith from those who practice the kinds of witchcraft that was passed down through generations or written about in historical accounts.

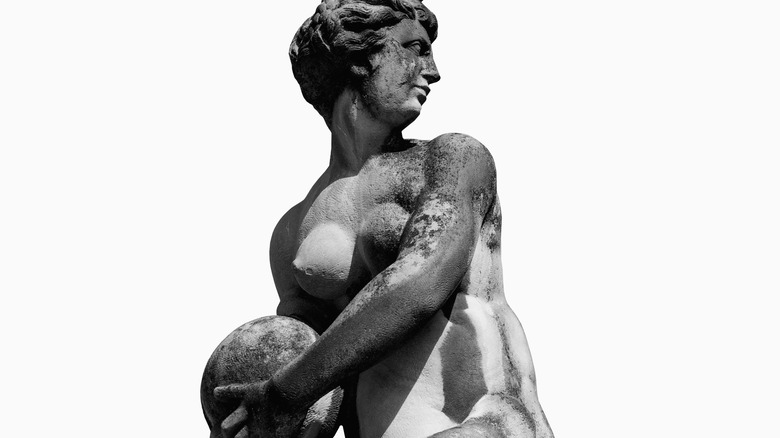

Wiccans primarily worship a goddess

While many Wiccans are polytheistic and worship several different deities that have personal importance to each individual, there is also one goddess and god that most of them hold chief among them rest. The Mother Goddess, often called Gaia, is the supreme being and creator of all life. According to the Digital Occult Library from CUNY, Gaia is often accompanied with a male deity commonly known as the "Horned God," or Cernunnos, who shares characteristics with an ancient Celtic deity and the Greek god Pan.

Yet in 1971, the second-wave feminist movement was gaining momentum and heavily influenced Wicca to form the Dianic sect of the religion. To these worshippers, the emphasis on the female deity became stronger than ever before, says Britannica. Author Diane Smith in "Wicca and Witchcraft For Dummies," not only confirms the special position of the goddess in the religion, but even reveals that some only worship Gaia alone and no male god at all.

As an ancient practice that is also thoroughly widespread amongst numerous cultures, witchcraft, in general, does not place any significant importance on any specific deities, whether female or male, as Quartz notes. In both the distant past and present, the followers of a huge range of gods and goddesses have all been accused of, or admitted to, practicing magic rituals of witchcraft.

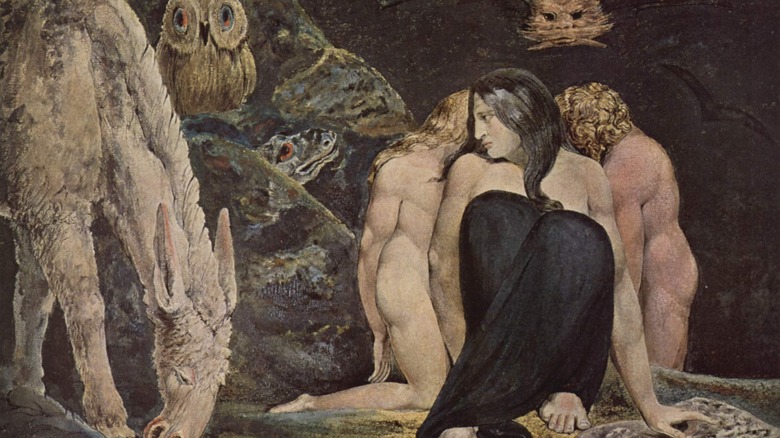

Some Wiccans believe the gods are symbolic

Even though there is solid evidence that atheism was more common in the ancient world than previously thought, as per the University of Cambridge, many cultures had multiple gods, which led to deities for just about everything who were worshiped by the majority of the populace. For many practitioners of witchcraft in the Greco-Roman world, the obvious choice to worship was Hecate, the goddess of witchcraft (via World History Encyclopedia), but there were also several other gods and goddesses whose cults were strongly linked to magic rituals as well. Since most pagans revered the gods at the time, those who practiced magic were no different.

In the modern age, atheists have become far more prevalent, so that mindset has made an impact on Wicca too. According to Beliefnet, there is an entire branches of the religion that does not believe gods exist. To these atheist Wiccans, the deities are considered either symbolic or archetypal figures, per Britannica, and the deep respect for all life is more important than the worship of supernatural beings.

Wicca is not connected to Satanism

Like Wicca, the modern religion of Satanism is also closely associated with witchcraft with many of its adherents calling themselves witches too. However, over the decades, Wiccans have made it absolutely clear that they have no connection to Satanism whatsoever. In fact, Wiccans are so opposed to the idea of Satan that they claim he does not even exist, says author Stephen Hayes in Missionalia.

And yet, people outside both groups consistently make the mistake of linking Wicca with Satanism to this day. The Digital Occult Library suggests that the main reason for the erroneous connection is the Horned God worshipped by Wiccans who many mistake as the devil. Plus, Britannica points out that many Evangelical Christians made the situation much worse by strongly promoting the idea that the two groups are the same. Their anti-Wiccan campaigns intensified dramatically in the 1980s and '90s when hysteria over Satanic rituals was at its peak.

Witchcraft was historically described by outsiders

For the vast majority of the times that witchcraft is mentioned in the ancient sources, it is in reference to a crime that was allegedly committed by supernatural means. Thus, many of these cases were written about by those who placed judgment, not by the accused whose perspectives are often nonexistent in the historical record. Britannica states that those accused of witchcraft came from all backgrounds and could be any age or sex. But just because someone faced accusations that they were a witch, sorceress, wizard, or any other similar label, did not mean that the accused considered themselves as such, or even practiced witchcraft in the first place. Convictions for witchcraft were a convenient way of removing enemies, so accusations occurred far too often, as Britannica notes in the case of the Salem witch trials.

Conversely, Wiccans are free these days to explain their own beliefs, as Britannica notes. In many parts of the modern world, those who identify as witches do not have to face the same barbaric persecution as their ancient kin, and hopefully, never will.

Witchcraft is often associated with supernatural powers

Especially in the distant past, witchcraft has traditionally been closely associated with supernatural abilities. These extraordinary powers could be inherent within an individual or a skill that witches learn through training and practice, the latter of which is an idea more common in European civilization, per Britannica. Around the world, there are also many other cultures who believe a witch's power is derived from gods or spirits who bestow it upon them, leading to the negative view that they followed demons in order to obtain the unnatural abilities.

The Wiccans viewpoint, on the other hand, has been shaped by modernity, with many having a desire to seek a logical explanation for magic based in the natural world. Yet whether it is seen as supernatural or not, all Wiccans believe in magic of some kind, and an accurate way to sum up their perspective on the matter comes from the words of the famous occultist Aleister Crowley, who described magic as "the science and art of causing change to occur in conformity with will" (via Beliefnet).

Most cultures worldwide have their own version of witchcraft

Even though there are arguments against the theory, religion is so common throughout the world that it is often seen as a default setting for human societies, according to the University of Cambridge. Similarly, the shocking prevalence of witchcraft suggests that the same could possibly be said for that practice as well. Historian Ronald Hutton said (via The Atlantic), "There is little doubt that in every inhabited continent of the world, the majority of recorded human societies have believed in, and feared, an ability by some individuals to cause misfortune and injury to others by non-physical and uncanny ['magical'] means."

Over the decades since its creation in the mid-20th century, Wicca has adopted several aspects of witchcraft and magic from various cultures across the globe, such as from North Africa, Western Asia, and even a little bit of Hinduism as well, says Britannica. However, the religion is still predominantly based on beliefs rooted in Europe. Thus, witchcraft in general is considerably more widespread than its most popular religion in the Western world.

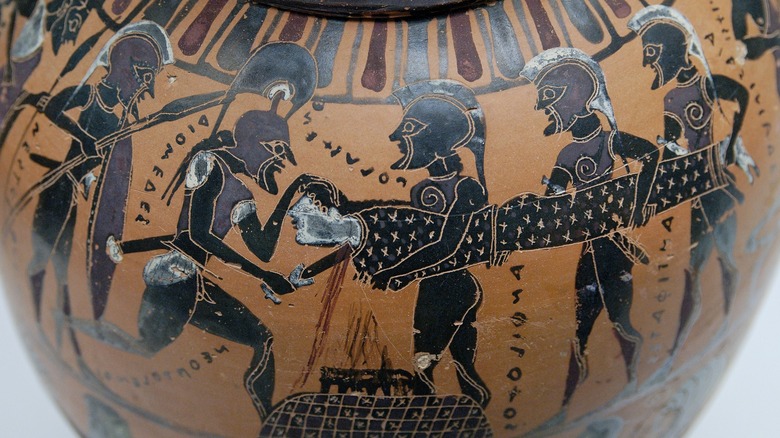

Wiccans would never commit sacrifices

One of the darkest features of many cultures from the ancient past is how common ritualistic sacrifices were, both of animals and even humans as well. From the Greeks, to the peoples of Mesoamerica, and the Japanese, sacrifices have existed at some point in nearly every civilization across the globe, according to The Washington Post. The use of the archaic practice included the pagans of Europe too, such as the druidic religion of the Celts, according to medieval historian Lisa Spangenberg on her blog, Digital Medievalist.

Among the ancient European pagans, far more common than human sacrifice was the ritualistic slaughter of livestock. As author Diane Smith points out in her book, "Wicca and Witchcraft For Dummies," these rituals were a part of festivals that coincided with agricultural cycles. So, regardless of how brutal the practice may seem to individuals today, it served a logical purpose for survival as the meat was preserved for the winter months when food was scarce.

Wiccans, on the other hand, are unlike their pagan forebears in that they would never commit any sacrifices. Not only is such a thing unnecessary in the modern age, but the core of their objection truly comes from their complete refusal to cause harm to living creatures, which definitely includes animals as well.

Wicca is rarely a death sentence

Many people often associate witches with the persecution they received from Christians in the early modern period. However, since witchcraft was often considered the way of using supernatural means to cause harm or commit murder, those who were found guilty of performing the practice were also executed before the advent of Christianity. The ancient Germanic tribes burned alive those who committed witchcraft, and the guilty would have met a similar, brutal end in the Roman Empire as well, as per Missionalia.

In the Middle Ages, the practice of witchcraft remained an executable offense, but the persecution did not reach its height until the European Renaissance. According to the Digital Occult Library, as many as 100,000 to 300,000 people could have been murdered for the crime from 1300 to 1700. During this period, an accusation of committing the act was pretty much the same as handing out a death sentence, says Beliefnet.

Fortunately, the barbaric executions of those who perform witchcraft are now extremely rare in the modern world, especially in the areas where Wicca is prevalent. Today, witches may still be viewed as outsiders and scapegoated in society, yet that is likely to be the extent of the persecution they are ever forced to face for their beliefs.