A Harvard Astronomer's Stunning Theory About A 2014 Meteor Deep In The South Pacific

Among all the phenomena of the night sky, nothing is quite as magical as a shooting star. Sure, comets are more magnificent, but they only come around every 10 years or so. Shooting stars are falling all the time, and with a little patience, you're bound to see at least one on a clear night.

Technically speaking, shooting stars are more properly called meteors. Most of them were originally part of the asteroid belt and got dislodged from their orbit by a passing planet and ended up finding their way to our planet (via Astronomy). NASA estimates over 48 tons of meteors enter our atmosphere every day, and of the 25 million or so that fall into our gravity; well, about 17 manage to impact the surface, leaving behind a valuable treat for collectors (via Cosmos).

But not all meteorites (a meteor that has impacted the Earth) are made the same. As said, most of them come from the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. Some of them, however, come from the debris trails left behind by passing comets from the Oort Cloud or Kuiper Belt. And on at least one occasion, the Earth has scooped up a meteor from beyond the solar system.

Let's talk about meteors

Shooting stars, roughly speaking, have three life phases. When they're floating through outer space, they're called meteoroids. As they streak through the night sky, they're called meteors. And, if they survive their searing trip through our atmosphere, they're called meteorites (via NASA).

It's not common for meteors to be observed impacting the ground. Typically they're found many years after the fact. So how do we know they come from outer space? They're old. Here on Earth, rocks are constantly being recycled (albeit very slowly), and so are a couple billions of years old at the high end. Rocks from outer space are 4.5 billion years old (the oldest rocks on Earth are 4.25 billion years old) because they formed with the solar system and haven't undergone any meaningful changes since that time (via Arizona State University).

Because meteoroids are orbiting the sun just like the Earth is, they're traveling pretty fast. The Earth is hustling around the sun at over 18 miles per second. In order for them not to fall into the sun, meteoroids need to be traveling at least that fast. But because meteoroids can hit us from any angle, they can be traveling anywhere between seven to 44 miles per second relative to the Earth when they ignite in our atmosphere (via the American Meteor Society).

Interstellar visitors

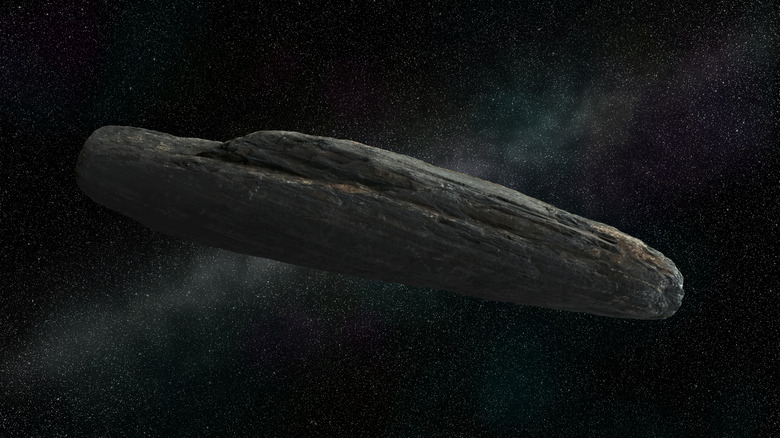

In 2017, the first known interstellar object — Oumuamua — entered our solar system. The determination of its interstellar origin was made due to the speed it was traveling relative to the sun (over 50 miles per second!), and the direction it came from.

Two years later, searching for other potential interstellar visitors, Harvard professor Avi Loeb and then-undergraduate Amir Siraj undertook a hunt for any out-of-the-ordinary meteors in NASA's Center for Near-Earth Object Studies database. In just a few days, Siraj found a likely candidate in an object that plunged to Earth off the coast of Papua New Guinea in 2014 (via Scientific American).

Based on just the information available in the CNEOS database, the 2014 meteor (officially called CNEOS 2014-01-08) was traveling nearly 28 miles per second relative to the Earth. This speed alone was already enough to hint this could be an interstellar visitor, but when Siraj teased out the numbers, he found that the meteor entered the atmosphere on the back side of the planet as it spun around the sun, giving it a speed of 37 miles per second relative to the sun, faster than anything in the solar system.

Publish or perish

If what Amir Siraj and Avi Loeb found was indeed an interstellar meteor, then that would make their discovery the first-known detection of an object from outside the solar system. All they had left to do was publish the paper proving their findings.

There was just one problem. The data they relied on, the information in the CNEOS database, came from a partnership NASA had with the Department of Defense. To give credence to their extraordinary claims, Siraj and Loeb would need to know the margins of error for their data. But, because that data belonged to the Department of Defense, and could be used by enemies of the U.S., it was classified. Without that data, their paper languished in preprint purgatory for three years (via Scientific American).

The pair had roughly deduced what the margins were by comparing publicly available data with other meteors in the CNEOS database, but the rigors of science demand more than just speculation. They had even received confirmation of their numbers from an anonymous source but it wasn't until 2022 that they were validated via a memo from the U.S. Space Force, confirming their conclusion that CNEOS 2014-01-08 was an interstellar object (via Twitter).

Interstellar oddity or technosignature?

The fact that this meteor originated outside of our solar system is interesting enough, but there are some other oddities about CNEOS 2014-01-08 that lead Amir Siraj's mentor, Avi Loeb, to suggest some extraordinary possibilities.

It's already been mentioned that the meteoroid was traveling 37 miles per second (133,200 mph) relative to the sun. For an object to attain those kinds of speeds relative to our system, it would have had to originate either in the heart of an alien solar system, or traveled from deep in the interior of the galaxy (via arXiv).

It was also very tough. The strongest meteors intercepted by Earth are made of mostly iron. Based on the flares produced by CNEOS 2014-01-08 and the estimated altitudes at which they occurred, Siraj and Loeb estimate that it must have been about twice as strong. In fact, it's stronger than every other object in the CNEOS database to which they could compare it.

Given these incredible conclusions, it's possible the meteor was formed close to a supernova or a neutron star merger, where it acquired its heavier-than-normal composition and remarkable speed. Or, according to Loeb, it could be artificial in origin (via Salon).

The hunt begins

Regardless of whether CNEOS 2014-01-08 is natural or artificial in origin, the fact that there may be pieces of an interstellar object on Earth is extraordinary. The prospect of finding pebble-sized bits of debris from outside the solar system is so tantalizing to Avi Loeb, that he's attempting to mount a $1.5 million expedition to find them at the bottom of the Bismarck Sea off the coast of Papua New Guinea (via NPR).

The plan is as simple as it is audacious. Loeb plans to charter a boat and scour 40 square miles of the sea bed with an underwater sled equipped with a magnet searching for any potential fragments of the meteor. Loeb's theory has plenty of detractors in the scientific community, but despite the skepticism, he's still managed to raise half of a million dollars so far, reports Salon.

Besides CNEOS 2014-01-08 and Oumuamua, astronomers have found only two other interstellar objects. In 2019, an amateur astronomer found a comet going 110,000 mph through the solar system. And in September, Amir Siraj and Loeb found another potential interstellar meteor in the CNEOS database.