What We Got Wrong When Studying The Extinction Of Steller's Sea Cow

It's quite tragic to think of the weird and wonderful animals that we'll never see again. Extinction has cruelly claimed the lives of a huge variety of species, from the Tyrannosaurus Rex to the dodo. In the case of the dinosaurs, according to the Natural History Museum, the Cretaceous period came to an abrupt and horrific end 66 million years ago. Exactly what caused the catastrophe is unclear, but a combination of the changing climate, an asteroid impact, and other natural disasters are believed to have contributed to the mass extinction.

More contemporary extinctions and near-extinctions were, tragically and inevitably, caused or heavily influenced by humans. For instance, the Buffalo Field Campaign states, via the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, that up to 60 million lived in North America on the arrival of European settlers. By the turn of the 20th century, disease and hunting had decimated the species to the point that, per the National Park Service, only about 24 bison remained in Yellowstone.

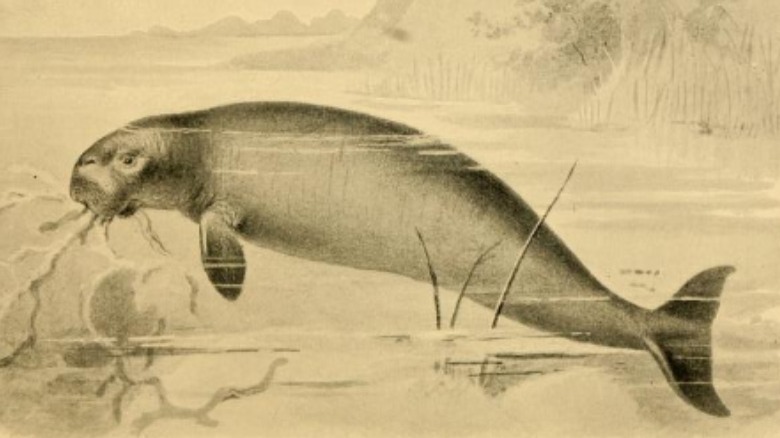

The extinction of the Steller's sea cow, it seems, was one that was believed to have been caused (to a great extent) by humans. However, it appears that this glorious creature (which has much in common with the modern dugong, as pictured above) was doomed even before our ancestors came along.

Humans aren't (entirely) to blame for its extinction

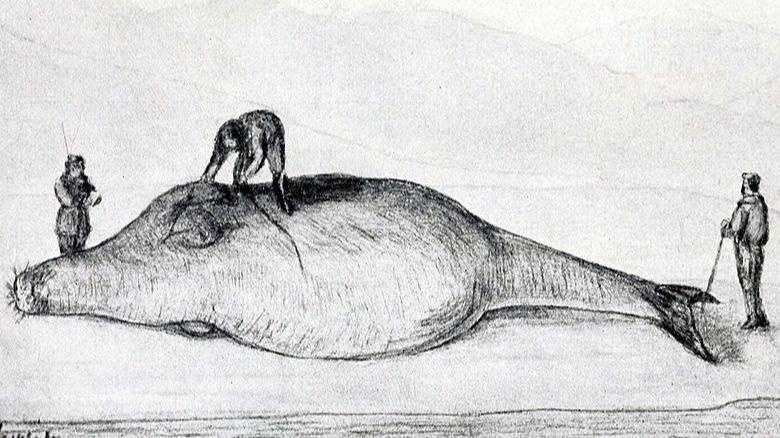

Steller's sea cow, according to Britannica, was a large aquatic mammal. It had much in common with present day sirenians, the dugongs and manatees, but was far larger. Far, far larger: Steller's sea cow could reportedly weigh in excess of 22,000 pounds (11 tons), and reach 30 feet in length.

The website goes on to report that this enormous, noble beast was identified in 1741 by naturalist Georg W. Steller (for whom, of course, it was named). According to the U.K.'s Natural History Museum, Steller's limited observations of his sea cow would be the only scientific ones humanity got a chance to make: by 1768, they were reportedly extinct.

They were wiped out, per the Natural History Museum, by hunters pursuing the glorious fur coats of sea otters. Steller's sea cow happened to live only in the chilly Northern Pacific where the otters were found, and so they were killed for their meat en masse — collateral damage in the pursuit of fashion. It would be easy to conclude that hungry humans alone were responsible for the extinction, as they certainly devastated the numbers. However, a 2021 study has concluded that the tragic extinction of this marvelous creature began long before human hunters wiped out its remaining population.

A tragic ciao to the sea cow

In April 2021, Fedor S. Sharko et al published the paper "Steller's sea cow genome suggests this species began going extinct before the arrival of Paleolithic humans" (via Nature Communications). It states that the last surviving Steller's sea cows lived around the Commander Islands of Russia, and were killed by "sailors and fur traders hunting it for the meat and fat."

That seems par for the course with humanity at times, but this wasn't the only factor in the loss of the Steller's sea cow. The study reports that it was previously believed that climate and sea level change millions of years ago, as well as hunting from our ancestors, reduced the population of the species to levels that left them ripe for extinction in the 1760s. What the researchers did, though, was use the genome of the Commander Islands Steller's sea cow and, through it, "investigate the population history of this marine mammal during the last several millions of years in the Bering Sea region."

By using DNA from the petrous bone of a specimen, and through comparison with other marine creatures, the team determined that "Steller's sea cow definitively embarked on the road toward extinction long before the arrival of the first Paleolithic hunter-gatherers in the Beringia, which is estimated to have occurred at least 25,000–30,000 years ago." Unable to reach deeper depths, they were more susceptible to changing sea levels, which restricted their access to the algae they ate.