Most Chaotic Presidential Elections In US History

Regardless of which side you're on, we can all agree that politics suck. Our current political moment is all-consuming, and not in a good way. It's defined by infighting, conspiracy theories, congressional gridlock, extreme political polarization, rising authoritarianism, cults of personality, and a general belief that if the other candidate wins, we're all doomed.

But the thing is — and we're not sure if this will make you feel better about the scary and sad state of affairs, or worse — this kind of stuff isn't exactly new.

Since the country's inception, politicians — including leaders you were taught to admire in social studies class — have engaged in finger-pointing, name-calling, slander, infighting, cronyism, corruption, and all other forms of scandal and immaturity. And that's just the kind of chaos deliberately caused by candidates, not the wild stuff that's out of anyone's control.

And presidential elections are where all that stuff comes to a head: When people who haven't even recovered from the stress of the last election are forced to pay attention to prevent the dang country from imploding. From numerous Electoral College ties to sleazy backroom negotiations to political parties that can't even decide on a single nominee, these are the most chaotic presidential elections in U.S. history.

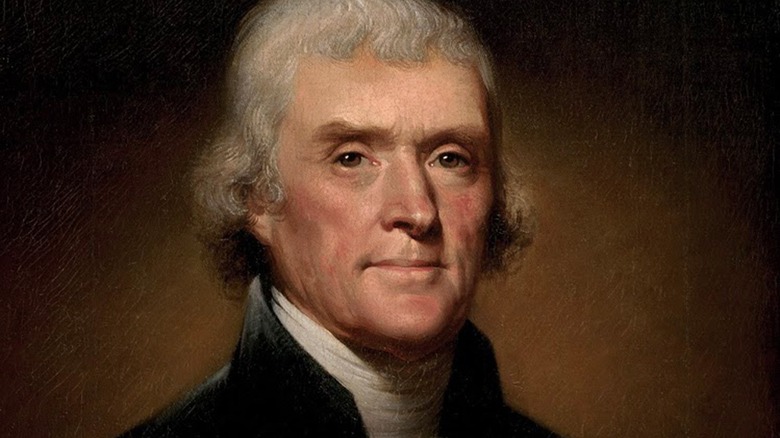

1800: Jefferson vs. Adams (vs. Burr)

You'd be surprised how fast some of the Founding Fathers, whom we imagine as towering beacons of wisdom and maturity, turned to vicious squabbling, name-calling, and claims that the other side winning would unravel the country — the sort of distasteful but depressingly familiar hallmarks of our own political system today.

The 1800 presidential election pitted Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson against incumbent Federalist John Adams. According to USHistory.org, Adams smeared Jefferson as a godless revolutionary who secretly sought to recreate the violence of the French Revolution in the United States. Meanwhile, Jefferson's party, including vice presidential nominee Aaron Burr, attacked Adams' Federalist party, claiming they were depriving states of the right to govern themselves and acting as tyrants, as evidenced by the highly controversial Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 (via the National Archives).

But when the votes were tallied, it was Jefferson and his own running mate, Aaron Burr, not Adams, who had tied in the Electoral College (this was before presidential and vice presidential candidates ran together), meaning the race would ultimately come down to the House of Representatives. So to summarize, incumbent President John Adams had been eliminated, and the race was now between his challenger and that challenger's own running mate. That's wild enough — but the chaos wasn't over.

After numerous deadlocked ballots in congress, Federalist Alexander Hamilton rallied his party for Jefferson, who finally won the presidency. The move greatly contributed to the rivalry between Hamilton and Burr, which ended in an infamous, deadly duel on July 11, 1804, per History.

1824: Jackson vs. Adams vs. Crawford vs. Clay

In 1824, the country was getting ready to choose its sixth president, who would replace incumbent James Monroe (via the National Endowment for the Humanities). At this early stage of its history, the United States was still very much finding its political footing. Presidential nominations had, up till then, been contentious, undemocratic affairs that drew scrutiny from across the country for essentially picking possible presidents in shady backroom negotiations. For a time, the "King Caucus" system reigned, according to via Britannica: Since the Democratic-Republicans were briefly the only viable political party following the demise of the Federalists, their nomination conventions were essentially coronations. But this was so despised and undemocratic that it was done away with by 1824.

The 1824 presidential election was the first one where candidates were themselves voted on before a general election. But in this particular instance, the country went from the frying pan of not having enough candidates into the fire of having too many, all from the same party. The Democratic-Republicans collapsed into chaotic infighting when there was no other party to unite against.

In the end, Andrew Jackson won the most votes, but failed to secure an Electoral College majority (via the Library of Congress). After the race was thrown to congress, popular vote runner-up John Quincy Adams won the election by securing the electoral votes of defeated candidate number four, Henry Clay, in exchange for naming him secretary of state.

Jackson bitterly derided this "corrupt bargain." He vowed revenge and got it four years later, winning the 1828 election outright (via Britannica).

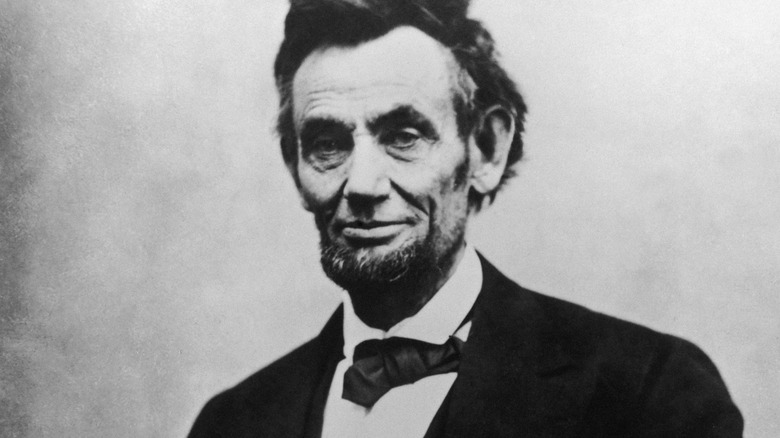

1860: Lincoln vs. Breckinridge vs. Douglas

America was struggling in 1860. Not only had the country just had two lousy presidents who did nothing to reign in the worsening slavery crisis (Franklin Pierce, according to U.S. News & World Report, and James Buchanan, as per History), but the Supreme Court's Dred Scott decision made things worse (according to PBS) by ruling that Black people could never be citizens and therefore could not sue for freedom in court. It was becoming frighteningly clear that the country was running out of ways to solve the slavery issue without violence.

Britannica details the election itself. Northerners outraged by the Dred Scott decision and the behavior of pro-slavery Southerners rallied behind Abraham Lincoln, the first nominee for the new, anti-slavery Republican Party (then representing northern liberals). Meanwhile, conservative Democrats were fiercely divided. After numerous national conventions and compromises failed to produce a single victorious candidate, both John C. Breckenridge and Steven Douglas ran on the Democratic ticket, each claiming to be the party's true nominee.

On Election Day, Abraham Lincoln won easily, despite carrying less than 40% of the national vote, due to the vote-splitting division on the other side.

To say this sent alarm bells through the South would be an enormous understatement. Believing their slave-holding days were numbered and that they could no longer hope to gain favorable outcomes through the political process, multiple southern states seceded to form their own country: the Confederate States of America. The American Civil War was about to begin.

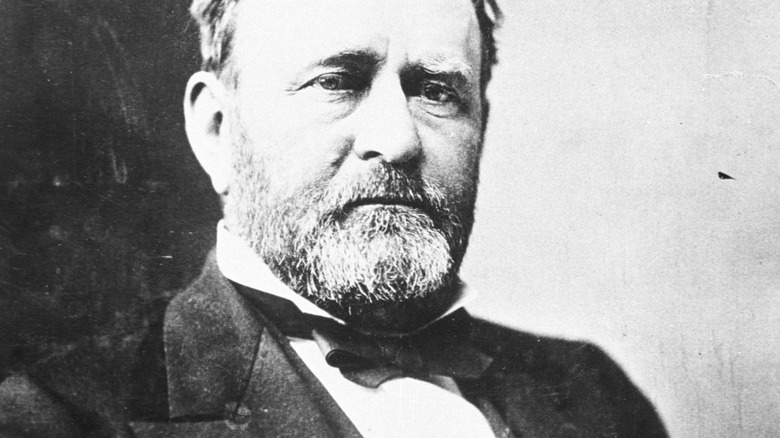

1872: Grant vs. Greeley

Ulysses S. Grant ascended to the White House in 1868 after his triumphant performance in the Civil War made him a national hero. The Democrats nominated Horace Greeley to oppose him four years later when he was up for re-election in 1872, per Constituting America.

Neither candidate, it turns out, was a natural politician. Grant, though still broadly popular, had seen his star dim a bit since the war ended. Greeley, meanwhile, was smeared as a Confederate sympathizer after he advocated for amnesty for guys like Jefferson Davis, president of the defeated Confederate States during the Civil War, who liberals thought of as traitors (via Britannica).

But not even Grant's swapping out of VP Schuyler Colfax for Henry Wilson nor the presence of the first-ever female presidential candidate (despite the fact that women couldn't vote yet), Victoria Woodhull, made this a "chaotic election." It was chaotic because of what happened following the November 5 election.

When the votes were tallied, Grant won the popular vote by a good margin over Greeley: 56% to 44%, and everyone prepared for Grant's second term. Then, however, Greeley died unexpectedly on November 29, before the Electoral College could vote and make Grant's re-election official. As a result, Greeley's 66 electoral votes were distributed amongst four individuals (totaling 63 [plus 3 for Greeley], per the Library of Congress). Grant received 286 electoral votes and the win. It was the first time in history electoral ballots were cast for a dead man. Imagine if he had actually won the election!

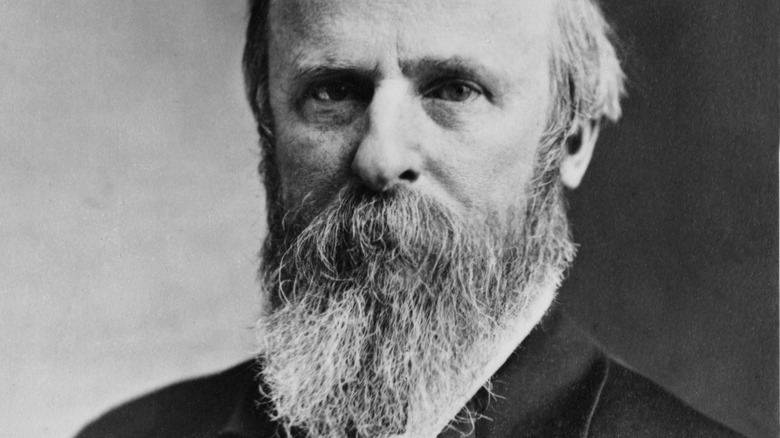

1876: Tilden vs. Hayes

If you're alarmed at the state of American democracy right now, there are two facts that might comfort you. First, you're not alone. Second, extreme (sometimes violent) political polarization, authoritarianism, populism, widespread political disenfranchisement of minorities, and levels of corruption and gridlock that threaten to shipwreck the country, are nothing new in the U.S.

You might think we're referring to the Civil War, which was undoubtedly the worst it's gotten so far. But while that conflict ended slavery for good and preserved the Union, it didn't solve all of America's problems. In fact, the Reconstruction period that followed was a trying time for the country in its own right.

In the presidential election of 1876, neither Democrat Samuel Tilden nor Republican Rutherford B. Hayes won outright, according to Britannica. In multiple states, both parties dispatched electors after violent and contentious elections, setting up an unprecedented constitutional crisis and throwing the decision to congress.

Finally, the bipartisan congressional committee established to sort out an election that already had the country on the brink of another Civil War came up with a compromise: Hayes would win, keeping the GOP in control of the White House, if he removed federal troops from the South and ended Reconstruction. Hayes accepted and the Democrat-led House barely voted in favor, according to the Miller Center. But Federal protection for Black southerners evaporated as a result, setting the stage for a horrific white supremacist crackdown of African American rights that would last for decades.

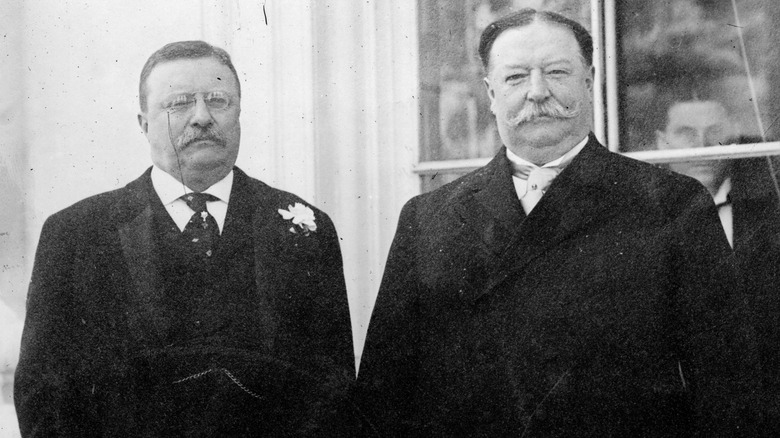

1912: Roosevelt vs. Taft vs. Wilson

As many have recently learned, politics can kill a friendship. Especially if those friends are the guys running. In 1912, former President Theodore "Teddy" Roosevelt was unhappy with the direction incumbent Republican and (soon-to-be former) friend William Howard Taft had taken the country and party. According to USHistory.org, there's disagreement among historians as to what motivated Roosevelt to throw his hat in the ring as a third-party candidate, leading the progressive Bull Moose Party. Some say he did it out of genuine concern that the progress he had overseen years earlier was in jeopardy. Others claim his giant ego had something to do with it. The truth may be somewhere in the middle.

But the important thing is, he did it. Throughout the year, Roosevelt and Taft turned on each other like only former friends possibly could. Things got ugly. As Britannica points out, it soon became clear that Taft, despite being an incumbent president with the backing of his party establishment, was not going to win against Roosevelt's "Republican insurgents" — progressives with widespread popular support. However, Taft made it his life's mission to take Roosevelt down with him.

Interestingly, much of the progressive vote Roosevelt was counting on went to Democrat Woodrow Wilson, who — facing a fiercely divided opposition — won handily with 435 Electoral College votes. Roosevelt was runner-up with 88, and Taft had only 8, per the National Archives. Needless to say, the Bull Moose Party didn't quite catch on afterward.

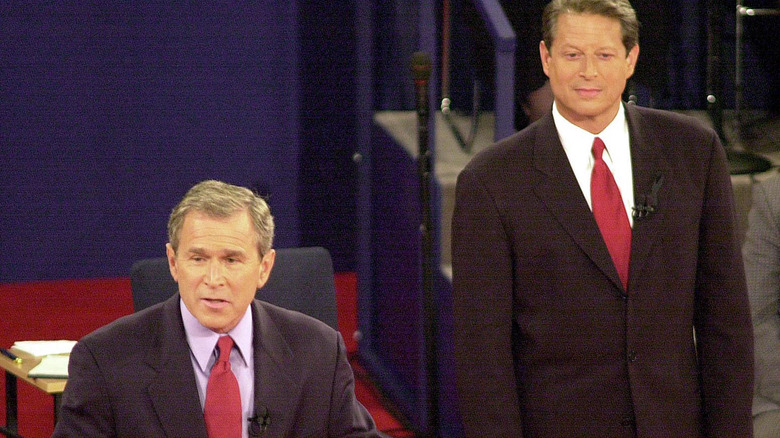

2000: Bush vs. Gore

In most elections, it only takes a few days at most to determine the winner. But in 2000, it would be nearly a month before anyone knew if incumbent Democratic Vice President Al Gore or Republican George W. Bush, then the governor of Texas and the son of former President George H.W. Bush, had won.

As History explains, polls showed a tight race in the home stretch. On Election Day, it became clear that neither candidate would be able to secure a crucial majority in the Electoral College without the state of Florida, which was too close to call.

Now, a race being "too close to call" is nothing new in American politics, and global history being determined by the flip-flopping political whims of the Sunshine State has become something of a meme at this point. But this one was especially nail-biting, since the candidates were a mere 537 votes apart in what had become the only state that mattered.

Unfortunately, nobody could agree on how to handle "hanging chads" — paper squares dangling from a ballot that voters were supposed to punch all the way through. Recounts and lawsuits were both inevitable and inconclusive. Finally, the Supreme Court stepped in and called the race for Bush on December 12, who won the Electoral College 271-266, per Politico.

The case remains controversial, especially because Gore won the national popular vote by more than 500,000. But the Democrat conceded for the sake of the country.

2016: Clinton vs. Trump

The presidential race to replace Barack Obama was in full swing by mid-2015, as reported by History. On the Democratic side, Hillary Clinton — former first lady and New York senator, as well as incumbent secretary of state — got her party's nomination following an unexpectedly tough and bitter primary challenge from progressive champion Bernie Sanders of Vermont. On the Republican side, Chris Christie, Jeb Bush, Marco Rubio, Rand Paul, Ted Cruz, and several other establishment conservatives were facing off. But the eyes of the world were on a rambunctious meme of a candidate in their midst — proudly sleazy reality TV star and celebrity businessman Donald Trump.

Once dismissed as an impossible longshot who was only good for entertainment value, Trump proved to be a master of commanding media attention, shrugging off scandals that would've demolished any other candidate and, eventually, winning levels of support among conservatives that alarmed the world. With his outsider persona (blasted as dangerous inexperience by his opponents) and schoolyard bully approach to politics, Trump would dominate the primaries and would soon find himself facing off against Clinton in the general election.

In November, Clinton won the popular vote by nearly 3 million — but lost the Electoral College 304-227 (via the National Archives), and the presidency, following unexpected defeats in the Rust Belt states of Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. It was one of the most shocking upsets in modern political history, and began a period of political polarization and norm-shattering democratic backsliding in the U.S.

2020: Trump vs. Biden

Between the COVID-19 pandemic and the Black Lives Matter protests (as well as murder hornets, wildfires, and Kobe Bryant's death), 2020 was one of the most surreal, terrifying, and tragic periods in recent memory. Sadly, rather than being a calming, guiding hand, the government only made things worse.

The year began with Republican President Donald Trump's first impeachment regarding an extortion scheme in which he tried to withhold military aid from Ukraine until they delivered nonexistent dirt on presumptive Democratic nominee Joe Biden (via Britannica). After his acquittal, Trump spent the year undermining attempts to control the pandemic and exacerbating racial tensions during the BLM demonstrations. It didn't seem like things could get any more tumultuous, but the death and swift, controversial replacement of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg right before the election did just that.

When the Democratic ticket of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris won in November, Trump and his team continued insisting, without evidence, that the election had been rigged — something his supporters lapped up with their "stop the steal" chants when the votes were still being counted and the rapid proliferation of related conspiracy theories after the race had been called. After Trump's baseless attempts to overturn the election both via the courts and by illegally pressuring officials in swing states to do so unilaterally, his supporters stormed the Capitol on January 6, 2021, leading to five deaths, Trump's second impeachment, and global concern about the state of American democracy.