The History Of The National Association Opposed To Woman Suffrage

During the Constitutional Convention of 1787, the popular belief held by many of the Founding Fathers who helped draft the Constitution was that women should not have the right to vote and needed to be protected from the "evil" that was politics, according to Britannica. Of course, even then, that view was not held by everyone in society, including Abigail Adams who famously told her husband John to "remember the ladies" as they formed their new government (per National Archives). A turning point in this discussion came in 1848 at the Seneca Falls Convention in New York when well-known activists began to make the case that women should be able to express their own political beleifs in the same way as men (via History).

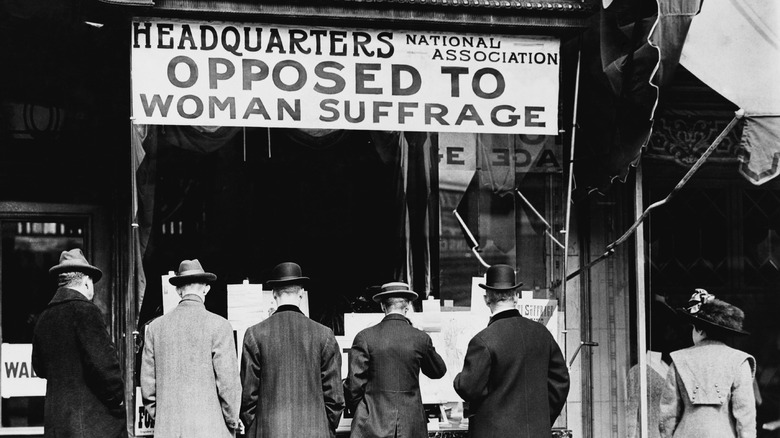

Yet, as the Women's Suffrage Movement began to pick up steam over the following decades, there was also a movement growing against permitting women to vote — a movement that included and was even led by women themselves. This anti-suffrage movement culminated with the formation of the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage in 1911. As noted by The Washington Post, it was an organization that argued that women shouldn't do the work of men and that politics fell into this category.

There were growing movements for and against women's suffrage

Since around the middle of the 18th century, there were active movements growing in the United States in support of and in opposition to women's suffrage. In most democracies during this century, voting laws continued to exclude women. As described by Britannica, as the world entered the 20th century, New Zealand was the only self-governing nation to permit all adult women to vote in national elections. According to History, the movement had been underway in the United States in the decades before the Civil War, but at the same time, the concept of the "Cult of True Womanhood" — or the belief that women should be submissive to their husbands and be in the home rearing children — was being popularized.

In 1903, theologian and author Lyman Abbott penned an article for The Atlantic arguing that women didn't want the right to vote. He contended that there was a "silent opposition" to voting rights among women that was often overshadowed and unheard because these women didn't involve themselves in politics. "[A woman] does not wish to engage in that conflict of wills which is the essence of politics," he wrote. "[S]he does not wish to assume the responsibility for protecting person and property which is the essence of government." Abbott was not the only one making this argument — there were, indeed, many women who believed it as well. They would soon organize their opposition.

There were men and women opposing women's suffrage

In 1902, activist Susan B. Anthony stated that if it were solely up to women, they would deny themselves the right to vote and that men were more progressive on the issue (per JSTOR). The reality is a bit more complex, but her comment demonstrates the frustrations of many women fighting for women's suffrage. As described by NPR, the women of the anti-suffrage movement were largely wealthier and of higher social standing. More often than not, they were married to men who were successful in business, politics, and the financial sector.

According to The Washington Post, motivations for opposing suffrage varied. In Molly Elliot Seawell's anti-suffrage book "The Ladies' Battle," she argued that suffragists were confusing politics with other things and didn't understand the constitution. One Harvard historian argued that men and women simply had "distinct" roles as citizens of the United States (per NPS.gov). For some, it wasn't about protecting their position in a privileged class, but a fear of disrupting the traditional family unit, which they argued provided them a different sort of power in society. This would be one of the many arguments of the New Englander Josephine Jewell Dodge, who would soon go on to found and become president of the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage.

Dodge founded her anti-suffrage organization in 1911

As the Women's Suffrage Movement gained momentum, the pushback against such changes increased as well. Leading this charge was Josephine Jewell Dodge. Dodge was born in Hartford, Connecticut in 1855 to a wealthy and politically-connected family (per Britannica). After marrying a New York businessman and involving herself deeply in issues of progressive social reform, she began to publicly oppose voting for rights for women, as she felt it would threaten what was perceived as the nonpartisan reform work of women. In 1911, she officially established the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (NAOWS) in New York City.

The New England Historical Society explains that these "antis" were often heavily involved in improving society's ills with poverty, poor living conditions for immigrants, awful prisons, and child labor. To politicize that, in their minds, threatened the work that they had been and were doing. In 1912, the events surrounding the sinking of the Titanic proved an example for Dodge, who penned an article in the organization's journal, "The Woman's Protest," wherein she argued that having women get on the lifeboats first demonstrated that women are not "fitted for men's tasks," (via The New York Times). Some of their messaging was more explicit. One of the organization's leaflets, for instance, contained a cartoon showing a woman holding a voting ballot like a baby, stating that she was hugging a "delusion" (per The Washington Post). Others showed women replacing men in various aspects of society.

The organization explained plainly why women did not need to vote

As described in a 1913 newspaper article (via The Washington Post), Josephine Jewell Dodge believed that national voting rights for women were not needed because state legislatures already protected women's civil rights. Such a "foolish" and "unnecessary" pursuit, she believed, was just women chasing "artificial happiness and unnatural enjoyment." There was a fear that women involving themselves in politics would take away from the community work, education, and charities that women were traditionally involved in. Dodge also stressed that this didn't mean that women were "inferior" to men, just different (per The New York Times).

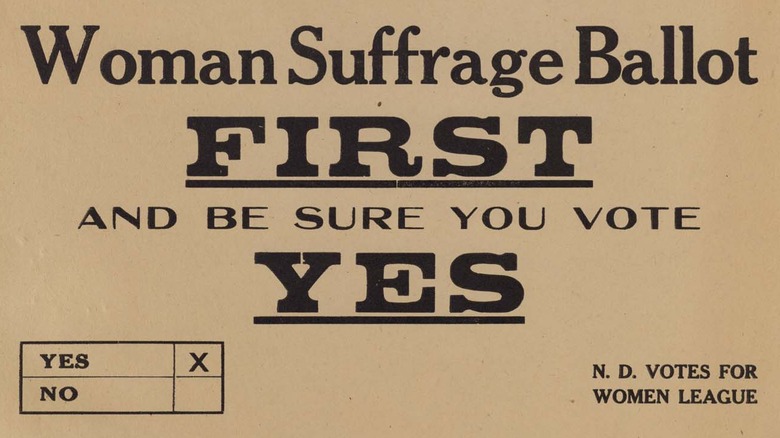

Furthermore, the anti-suffragists argued, the majority of women simply didn't want to vote, according to an 1894 pamphlet they published (via Library of Congress). On top of that, they asserted, permitting women to vote nationally would dramatically increase the costs of elections, and would take away the important role of men representing the interests of the women in their lives at the ballot box. Also, in states that permitted women's suffrage already, there would be no increase in "public and political morals," they wrote. It's unclear exactly how many women truly supported the views of Dodge and the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage, but it certainly wasn't fringe. Even Ida Tarbell, perhaps the best-known woman journalist of her era, was opposed to women's suffrage and wrote about it (per Library of America).

Some argued women should be nonpartisan in community involvement

Josephine Jewell Dodge and her followers did not believe that anti-suffrage meant women were expected to stay at home. On the contrary, instead of meddling in politics, they needed to be out in their communities. And if women were expected to be involved in their communities, therefore they didn't need the corrupting nature of politics influencing their philanthropy. They believed community work and social issues should be nonpartisan in nature. "[O]ur present duties fill up the whole measure of our time and ability," the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage stated (via Library of Congress), adding that women were outside of politics and, as such, could work with either party while involved with charity work. Renowned artist Helena de Kay Gilder asserted that women were equal to men and just as intelligent, but voting rights would be a "burden" that would attack women's liberty and corrupt them, according to The New York Times.

Others worried that involving women in politics would take away from their farm work, according to UNC Libraries. Others, as described by The Washington Post, simply believed that women belonged in the home and couldn't possibly run a homestead and be involved in politics. There were also many who were intimidated by the increasingly militant activism of the suffragists, as described in Doris Stevens's "Jailed for Freedom."

Chapters of the national organization formed at the state level

After the formation of the national anti-suffrage organization in New York City, state chapters throughout the country were organized. Here are some of the reasons women were denied the right to vote: The New Jersey Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage argued that women voting would demonstrate a lack of faith in their husbands, fathers, and sons to vote in a way that would be in their best interests (via New Jersey Historical Society). According to the Library of Virginia, their state chapter argued that women's suffrage would be outright disastrous for women and society. The Texas chapter proclaimed that "thinking women" had no interest in voting and then added in some casual racism arguing that it would increase the number of Black voters in Texas, per the Texas State Historical Association.

These state organizations all worked in tandem on a public information campaign connecting ideas of women's suffrage to progressivism and socialism, according to the National Park Service. Anti-suffragists increasingly began to allege that the women's suffrage movement was a result of not merely the spread of socialism, but also the increase of immigrants in the United States (via Western Michigan University). They ramped up the rhetoric with claims that juvenile delinquency would increase, marriage would be redefined, and women would begin to prefer "excitement" to running their homes.

They printed and circulated a weekly publication

The primary means for the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage to spread its message was through its weekly publication that, at its peak, had a claimed readership of over 600,000. The newsletter was called "The Woman's Protest" and then, during World War I, "The Woman Patriot." Its lead banner stated: "For Home and National Defense, Against Woman Suffrage, Feminism and Socialism" (per University of Western Michigan). In "The Woman's Protest," the authors analyzed suffragists' arguments and provided counterpoints. They also had letters from readers, compared laws in states that allowed women to vote with states that didn't, and provided book recommendations.

Anti-suffragist Grace Duffield Goodwin published a book, "Anti-Suffrage: Ten Good Reasons," in which she further connected the idea of being against women's suffrage to being patriotic as well as stating that when one relied on reason over emotion, the anti-suffragist stance was the clear and logical position. Numerous other books were published in support of the anti-suffrage movement as well. "The Case Against Women Suffrage," published opinion pieces, letters, quotes, and more writings that were all making the case against allowing women to vote.

Tensions were high between suffragists and anti-suffragists

After decades of disagreement, there was considerable tension between suffragists and anti-suffragists. During one incident, it almost turned into an all-out riot between the two sides. In a 1915 report, The Washington Herald (via newspapers.com) described a meeting involving both sides at the Democratic National Committee where activists began to hurl insults at one another, leading someone to accuse Josephine Jewell Dodge that she was simply money hungry. A yelling match ensued, which had to be broken up by the Sergeant-at-Arms. Dodge was ushered away, while suffrage leader Alice Paul said that the "disgraceful" accuser was not part of her immediate group. As described by the Library of Congress, this was not the norm, as, despite tensions, there was general civility between the two sides in most instances.

But this wasn't the first time that these tensions boiled over either. Two years earlier, it had gotten violent. Suffragists were marching in Washington, D.C. when a mob of mostly anti-suffragist men (it's unknown if they were connected to Dodge's organization) yelled and tripped and pushed marchers while police watched (per Library of Congress). About 100 marchers ended up being sent to the hospital. Despite this, they still finished the parade, according to the National Archives.

Members were often targeted as wealthy and corrupt women

Even if they were usually civil in person, insults were often slung between suffragists and anti-suffragists. Common accusations made toward anti-suffragists were that they were wealthy, corrupt, and had ties to the liquor lobby that viewed pro-temperance suffragists as a threat, according to "Woman Suffrage and Politics: The Inner Story of the Suffrage Movement." The suffragists, who were generally connected to the Progressive Movement, believed the "antis" to be in opposition to all things progressive and that they were controlled by corrupt, wealthy forces (per NPS.gov). Of course, this is the same accusation that Josephine Jewell Dodge and other anti-suffragists in her movement made against suffragists, contending that their involvement in politics would corrupt them (per UNC Libraries).

Meanwhile, anti-suffragists doubled down on implications that suffragists were unpatriotic, disloyal, and unwise (per UNC Libraries). Some even went as far as accusing women who wanted voting rights of being communists, according to The New York Times. In "The Case Against Woman Suffrage," author Everett P. Wheeler called suffragists "fanatics" who constantly lied, had "no appreciation for truth," and were "tempters" of sexual sin.

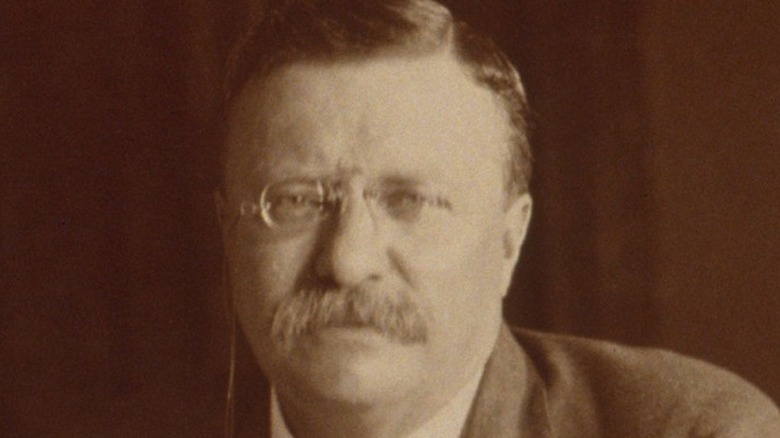

By the 1910s, they began to embrace anti-progressivism as an identity

By 1910, progressivism was all the rage with the less conservative members of society. By 1912, there was even a newly formed Progressive Party, formed by former president Teddy Roosevelt. While initially embracing non-partisanship, as the years passed, the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage increasingly became anti-progressive in its messaging. Both Roosevelt, as well as Socialist Party presidential candidate Eugene Debs, were supporters of granting women the right to vote. Debs was even on friendly terms with Susan B. Anthony (per Debs Foundation). As a result, Josephine Jewell Dodge and her organization began to connect women's suffrage to not only socialism but the entire Progressive Movement (per NPS.gov).

As described in "Women's Suffrage: The Complete Guide to the Nineteenth Amendment," this anti-progressivism wasn't always the case, as many members of the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage didn't see themselves as anti-progressive. After all, many of the anti-suffragist women were themselves involved in otherwise progressive social activism. Yet, as pointed out by The New York Times, to attract more conservative working and middle-class Americans to the anti-suffrage cause, they continued finding ways to make anti-progressivism part of their platform.

The organization broke up following the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment

Despite the efforts of Josephine Jewell Dodge and the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage, the Nineteenth Amendment passed in 1919 and went into effect in 1920, granting the vote to women across the United States (per Britannica). The text of the amendment was as simple as it was clear: "The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex."

While "The Woman Patriot" would continue being published for another decade in opposition to feminism and liberalism, Dodge's organization officially disbanded. According to The New York Times, Dodge continued to be active in her community, particularly with the National Federation of Day Nurseries and the New York Centre of the Drama League of America. She spent the last few years of her life mostly living abroad in France before dying in 1928. As for other members of the organization, The Washington Post notes that many of them ended up getting involved in politics. Some even ran for office and won.