World War II Pacific Front Timeline Explained

If Adolf Hitler's Nazi Germany had stood alone against the Allies, World War II probably would have played out a lot differently. As it happened, Germany had a few powerful allies of its own, and by the time Britain and France finally declared war on the European front, Hitler already had established ties with Imperial Japan.

It's a fascinating phenomenon: As The National WWII Museum points out, the feelings of racial superiority brandished by both Imperial Japan and Nazi Germany seem like they would be at odds with each other, with both ideologies firmly believing they were the best. That didn't happen, though, and at the same time Hitler was making a mad grab for power and territory in Germany and Europe, Japan was doing the same thing in China.

Influenced heavily by the Nazis' Joachim von Ribbentrop and Japan's Hiroshi Oshima, the two countries signed a pact in 1936. The Anti-Comintern Pact was initially designed to form an alliance against the two nations' Communist enemies — namely, the Soviet Union and China — without calling out either one specifically. The symbolic nature of it ended up being the most important part, and although it was on the surface a defensive partnership, it would soon kickstart World War II on a whole other front: The Pacific.

September 18, 1931: The Mukden Incident

While Adolf Hitler's invasion of Poland would be the spark that ignited World War II, it's worth taking a look at what was going on in Japan years prior because it was oddly similar. According to the National Archives (via the Harry S. Truman Library and Museum), Japan had very similarly marched its way into and through huge sections of China starting with an invasion of Manchuria in 1931.

Britannica says the whole thing really kicked off on September 18, 1931. That's when — after a long series of conflicts, bombings, and an assassination — there was an accusation made that the Chinese military had attempted to bomb a train. Following quickly on the heels of the incident, the Kwantung Army — which wasn't particularly under the authority of Tokyo's government — seized what was then called Mukden (and is now called Shenyang).

Just what happened still isn't clear, with the U.S. State Department's Office of the Historian noting that it's long been rumored that the bomb had been planted by the Japanese army and used as an excuse to kick off a takeover of Manchuria. Regardless, it ultimately allowed Japan to get a firm grip on abundant resources that would later become incredibly important, and they were allowed to do so fairly unchecked. With the West in the grip of a massive depression, not even economic sanctions were supported, and what was done to stop Japan had little to no impact.

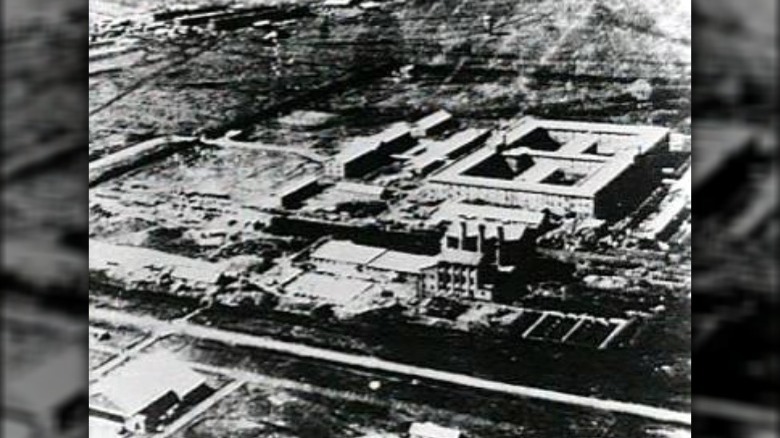

October 27, 1940: Unit 731 tests biological weapons on Ningbo

The Atomic Heritage Foundation says that when Unit 731 was formed in 1937, it was constructed for the purpose of conducting research into improving public health. In reality, it was conducting research into biological and chemical warfare using mainly Chinese and Russian test subjects.

Research done by biowarfare expert Tsuneishi Keiichi (via The Asia-Pacific Journal) shed some terrifying light on the top secret unit and the biological warfare trials carried out in China. The first trial involved releasing pathogens into the Holsten River, but because they lost their effectiveness in water, it didn't have the desired effect. The following year on October 27, 1940, Unit 731 initiated what would be one of its earliest trials.

Fleas infected with plague bacteria were dropped on the city of Ningbo, and it was both a success and a failure. The first person died four days after the drop and on November 2, the city was quarantined for widespread disease outbreaks, and 106 would eventually die from the trial. While it was one of the deadliest attacks, it was also deemed a military failure because of the effort that went into delivering the fleas.

The unit would go on to be linked to atrocities throughout WWII, including live vivisections, amputations, and other deliberate infections (via The Guardian). Japan didn't admit to the existence of the unit until 1988, despite years of attempts by the Chinese to raise awareness about the war crimes that had been committed.

July 1941: Japan invades Indochina

Conflict between Japan and the West throughout the late 1930s was perhaps best summed up by historian David M. Kennedy, who explained (via The National WWII Museum), "Each [nation] stepped through a series of escalating moves that provoked but failed to restrain the other, all the while lifting the level of confrontation to ever-riskier heights."

Things started to get really complicated in July 1940, when the U.S. government cut off Japan's access to key resources, including steel and aviation fuel. FDR's administration would only add oil to that list after Japan took aim at British Malaysia by moving into French-held Indochina, and here's where they started playing the long game. Half a world away, France had their hands full with the advancing — and occupying — Nazi army, which Berkeley's Cross-Currents says basically gave Japan the opportunity they needed to seize control of valuable territory and resources under what was now the Vichy government.

That led to FDR freezing Japan's U.S.-based assets, which included oil, and issuing a demand that Japan leave the territories it had conquered over the last decade. Japan refused, and as talks continued, they started planning major attacks on both British facilities in Singapore and American bases — including the one in Pearl Harbor.

December 7, 1941: Pearl Harbor

Most knew that history had been set on a course where the U.S. could no longer avoid getting directly involved in the combat of World War II after the attacks on Pearl Harbor, but what happened to lead up to that moment is oft-overlooked in American-centric tellings.

In the days leading up to the attack, Japan and the U.S. were deep in talks about how to avoid what was looking to be more and more inevitable. According to National Geographic, once the U.S. deciphered coded messages confirming an imminent Japanese attack should these talks fail, FDR put an end to the whole thing. That attack force was dispatched on November 26, and on December 1, they had their coded orders: "Climb Mount Niitaka." After taking a less-traveled, northern route toward Pearl Harbor that had been thoroughly mapped and documented in part by Japanese spies (including Takeo Yoshikawa, a spy based out of Hawaii's Japanese consulate), they took the base by surprise — but not because an attack was unexpected.

Pearl Harbor came as a surprise solely because it was so far away from Japan. Closer islands — like Guam and Midway — were on high alert because the attack was expected to happen there. By the time it was over, 19 ships were damaged or destroyed and 3,500 Americans were dead or injured.

April 10, 1942: Bataan Death March

It wasn't long after Pearl Harbor that Japan set its sights on another American outpost in the Pacific: the Philippines. The U.S. Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE) were created in July of 1941, and they were going to be tested in a brutal way.

The National World War II Museum says that by the time the Battle of Bataan kicked off, the troops of the USAFFE were already hungry, exhausted, and weakened by disease. The fighting was just the beginning, and after the April 9, 1942 surrender of the troops that had been tasked with stopping the Japanese advance into Manila Bay came the Bataan Death March.

About 80,000 POWs set out on the 65-mile march from the Bataan Peninsula to the internment camps where they were to be held. According to LiveScience, about 20,000 died along the way. Starvation and disease claimed countless lives, and survivor Ernest Miller described the misery: "Some of the men had reached a state of mind bordering insanity, from the lack of water. In desperation they would scoop it up from stagnant pools in the road ditches ... a stagnant pool is virtually alive with dysentery germs." Other eyewitnesses also testified to the execution of POWs along the way and at the camps with horrifying images. Soldier and survivor John Jacobs recalled: "[American GIs] went crazy, cut and bit each other in the arms and legs and sucked their blood."

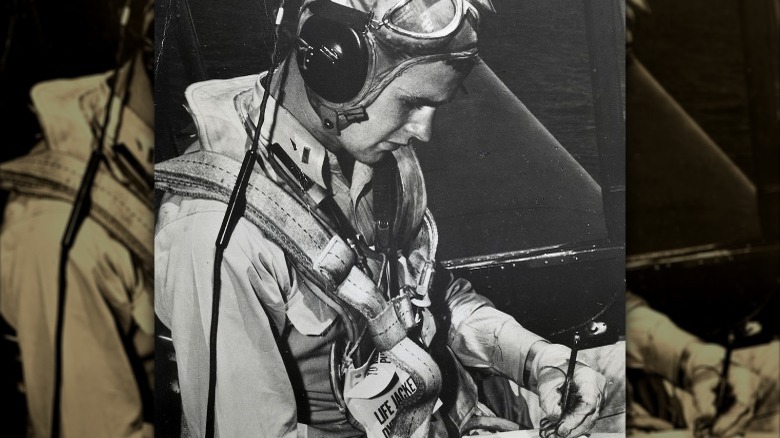

April 18, 1942: The Doolittle Raid

Naval History and Heritage Command notes that it was almost immediately after Pearl Harbor that the U.S. military decided they needed to make a point and hit Japan on their home turf. It was more complicated than it sounds at first, though. To do so, an aircraft would need to launch from an aircraft carrier and make it back and land there again, too. It was no small feat — and it was one suited to be led by veteran Lt. Col. James Doolittle.

The National Museum of the United States Air Force notes that the plan was pretty straightforward: They would launch from an aircraft carrier 650 miles off the coast of Japan, bomb key targets that included military installations, fuel storage, and factories — then continue on to land in friendly China. They didn't make it to the target runways, though, and when fuel started running out, each crew of the 16 bombers started to either crash or bail over China. Most survived with the help of Chinese civilians, but the aid given to Doolittle's Raiders came at a terrible cost.

It's estimated that around a quarter million Chinese civilians were killed in retaliation for giving aid to the American pilots — most survived, but eight were captured. Three were executed in Shanghai, one died in solitary confinement, and four survived to be freed in 1945. Those responsible for their treatment were tried for war crimes and found guilty.

June 4, 1942: Battle of Midway

If World War II's European theater was a battle of brute force, the Pacific was a chess game, necessitated by the sheer amount of strategic maneuvering needed to make attacks between islands. By mid-1942, the U.S. had deciphered enough Japanese communications to know that there was another attack being planned for either June 4 or 5 at a location known as "AF." Location is kind of a big deal, and according to The National WWII Museum, they discovered the secret location when communication was sent from the base at Midway claiming they were short on water, and a relayed (and intercepted) message indicated the same about "AF." On the morning of June 4, Japan attacked.

A U.S. naval force anchored by three ships — the USS Yorktown, the USS Enterprise, and the USS Hornet — was ready and waiting. The ships, their bombers, and their troops forced the surviving portion of the Japanese army to retreat. The conflict would later come to be called one of the most important battles of World War II — one that swung the momentum in favor of the U.S.

At the time, The Telegraph says the Japanese military had nothing but wins, securing Malaya, the Philippines, and Guam. If they had taken Midway, Hawaii would have been the next logical stepping stone on the way to the U.S. mainland, but that didn't happen. Instead, one Japanese witness would later report, "It seemed unbelievable. In seconds, our invincible carrier force had become shattered wrecks."

August 7, 1942: The Guadalcanal campaign

While some cite the Battle of Midway as shifting the tone of the Pacific away from the relentless forward march of the Japanese military, others argue that it was Guadalcanal that really changed things (via The Telegraph).

Guadalcanal marked the start of the Allied offensive in the Pacific. According to The National WWII Museum, the fighting at Midway and fighting at the Coral Sea, which occurred about a month prior on May 7 and 8, 1942, had crippled the Japanese military to the point where they were pushed back on the defensive. Still, the Guadalcanal campaign was far from easy. Made up of a series of battles and skirmishes, it was made more difficult by weather, terrain, disease, and difficulties in resupplying troops that were stretched to their breaking point.

The fighting dragged on for months, and it wasn't until February 1943 that Japan abandoned the island. With Guadalcanal held firmly by American forces, that kicked off the implementation of a strategy called island-hopping: Allied forces would target and take small, lightly defended islands and secure them in order to cut off supplies and access to Japanese strongholds. Those strongholds were left to starve, as the American military began to cut their way across the Pacific.

November 20, 1943: Battle of Tarawa

It's impossible to cover all the battles of the Pacific save for a multi-volume set of Encyclopedia Britannica-sized books. Still, those battles were all fought with some specific goals in mind, and in late 1943, the goal was to target the Gilbert Islands. The National WWII Museum says that this island was one in a series that would ultimately get the U.S. to a point where they were close enough to launch bombers that could reach Japan, and it goes without saying how big of a deal that was.

By the time Admiral Chester W. Nimitz set his sights on Tarawa, the U.S. military outnumbered the Japanese by about 10-to-1. The Japanese, however, were firmly established on Tarawa, and there was a massive problem: the island's coral reefs. That meant the men storming the beach had about 800 yards to walk through the water under heavy fire. Although the U.S. Marines secured the island after 76 hours of fighting, they also suffered losses equivalent to that of the six-month-long Guadalcanal campaign (via History). On the other side, there were only 17 Japanese defenders who survived the fighting.

December 28, 1943: Time reporter Robert Sherrod convinced FDR to tell the truth about the Pacific

The Battle of Tarawa was supposed to be a pretty straightforward win for the U.S. ... until it wasn't. On the front lines of Tarawa was Time reporter Robert Sherrod, who had traveled around 115,000 miles during his time spent covering the war in the Pacific. When he returned to Hawaii after Tarawa, Smithsonian says that he was pretty horrified at the tendency of the American media to paint a picture of a war that was definitely going according to plan, was easier than expected, and should be over soon — easy peasy, lemon squeezy.

Sherrod headed to Washington, D.C. on December 28, 1943, and ultimately met with FDR to discuss how much the public should know. To put things in context, it had only been a few months before — in September — that the media had published the first photos of casualties. The three dead men lay on a beach half a world away, and Sherrod said that it wasn't enough: The public needed to know the full scope of the fighting.

The Battle of Tarawa had been filmed, and after some serious debate and Sherrod's go-ahead, "With the Marines at Tarawa" was released on March 2, 1944. It's grisly, horrible, and brought the war into the homes of families who had said goodbye to their loved ones months or years before.

September 2, 1944: Chichijima Incident

Fighting in the Pacific dragged on ... and on ... and on. More telling than the statistics are the individual remarkable World War II stories — like that of the bomber crew shot down over Chichijima Island on September 2, 1944.

The pilot of the bomber crew, says History, managed to bomb the target even after being shot. He was heading back to his aircraft carrier when he bailed out of the plane before it crash-landed. The pilot, rescued about four hours later, was George H.W. Bush — who undoubtedly had no idea he would go on to hold the office of U.S. President. Bush went on to continue to fly other missions — for a total of 58 throughout the war — and what happened to the rest of his crew was a story that wasn't made public until years later.

Several crew members had died while bailing out. Others were captured by the Japanese, and according to 9 News, it wasn't until the 2003 publication of a book called "Flyboys: A True Story of Courage" that the world found out they hadn't just been taken prisoner, bayonetted and tortured: They had been eaten. During a war crimes trial, a Japanese orderly recounted how he had watched as the American captives had been cut open, their livers and thigh meat served to the island's high command. Much later, Bush told CNN: "Why me? Why am I blessed? Why am I still alive? That has plagued me."

February 19, 1945: Iwo Jima

Allied forces had known they were going to be targeting Iwo Jima for a long time: According to Naval History and Heritage Command, that had been decided at a conference that had taken place in the last week of September 1944. Why Iwo Jima? Because, says The National WWII Museum, it was a base of operations for Japanese fighters that had been intercepting and harassing the B-29s that were getting closer and closer to Japan.

According to History, nothing really went according to plan, starting with the fine, steep, ashy sand dunes that provided some serious difficulties for troops landing and trying to make their way to the interior of the island. A pause in fighting lured troops into a false sense of security, which ended with barrages from artillery stations scattered throughout the mountains. An estimated 70,000 U.S. troops landed on the island. Despite outnumbering Japanese defenders by about 3-to-1, there were more than 25,000 American casualties by the time the island saw a final major skirmish on March 25. The island was officially ruled to be secure the following day, but small groups of Japanese soldiers remained on Iwo Jima until 1949, per The National WWII Museum.

Was it worth it? That's been debated without end or resolution. While the original plan was to use the island as a base, that never happened. It was, however, used as an emergency landing site, and hosted more than 2,200 bombers in the last days of the war.

April 1, 1945: The invasion of Okinawa

Okinawa, says Naval History and Heritage Command, was considered the last step to getting the Allied military within striking distance of mainland Japan. To that end, the USS Indianapolis led the charge, leaving Iwo Jima on the same day their victory was declared. By the time the fight for Okinawa was over, it had involved 1,600 ships and some 350,000 people — including invaluable support from the British Royal Navy (via Imperial War Museums).

History says that the battle was a sharp contrast to D-Day in the European theater. The beaches were nearly deserted, and instead of guarding the beach, Japanese forces set up deep within the heavily forested, natural cover of the island. Battles were fierce, from the sinking of the Japanese battleship Yamato to hand-to-hand combat on Hacksaw Ridge to kamikaze attacks on Allied ships. The battle was ended by the ritual suicide of Generals Ushijima and Cho. When the fighting finally ceased, the dead included 110,000 Japanese soldiers, as many as 150,000 civilians, and 49,000 Allies. The Allies were now within reach of Japan, but the cost had been high, morale was low, and millions of Japanese soldiers were still waiting on the mainland.

August 6, 1945: The bombing of Hiroshima

On August 6, 1945, per the Atomic Heritage Foundation, the Enola Gay left the tiny island of Tinian at 2:45 a.m. Then, the plane's official log simply reads: "Bomb Away — 0915 — At Mishima, Circle E. Of Target [Mishima, sic: Hiroshima]."

According to the Harry S. Truman Library, President Harry Truman didn't even know about the existence of the Manhattan Project until he took over after FDR's death. Once successful tests confirmed that scientists had created the extraordinary deadly weapon, Truman issued a warning in the form of the Potsdam Declaration. Japan did not respond to the threat of "prompt and utter destruction," and the call was made.

It's estimated that upon impact, 80,000 died during the bombing of Hiroshima. There are no words more powerful than the words of those who were there, like Yoshito Matsushige. He lived less than a quarter-mile outside the total destruction zone around ground zero and managed to take the only photos of the bomb's immediate aftermath. He would later say that there were things he saw that he just couldn't photograph, recalling (via End of Empire) sights like the students from nearby high schools "covered with blisters the size of balls, on their backs, their faces, their shoulders and their arms. The blisters were starting to burst open and their skin hung down like rags. Some of the children even had burns on the soles of their feet. They'd lost their shoes and run barefoot through the burning fire."

August 9, 1945: The bombing of Nagasaki

The decision to drop a second atomic bomb on the heels of the first was made for a very specific reason, says The National WWII Museum. The idea was that a second bomb would give the appearance of an unlimited supply of American weapons, prompting a quick surrender.

On August 9, 1945, a bomb named Fat Man was dropped on Nagasaki, but that wasn't the primary target. That had been Kokura, the location of several factories that churned out ordinances and chemical weapons. The B-29 carrying Fat Man flew over Kokura first, but the city was saved — and Nagasaki was doomed — by the area's infamously shifting weather and cloud cover.

There has been an ongoing debate over whether or not President Harry Truman really needed to drop the bomb, with many — including Dwight D. Eisenhower — saying that Japan was on the verge of surrender anyway, and it was an unnecessary sacrifice of innocent lives in the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In 2020, The Guardian spoke with Truman's grandson, Clifton Truman Daniel, and he recalled his grandfather being asked if he had regrets. "My grandfather said, 'Hell, yes.'" Daniel said. "You don't do something like that without thinking about it." But Truman maintained that in the end, the decision had saved both American and Japanese lives. Daniel noted that in preparation for the Allied invasion of Japan, half a million purple hearts had been made ahead of time. They're still being handed out today.

September 2, 1945: Japan surrenders

Japan's formal surrender and the end of World War II came aboard the USS Missouri when — beneath the flags of the U.S., Britain, China, and the Soviet Union — Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu and General Yoshijiro Umezu signed the official document of surrender (via History). After signatures from Allied commander General Douglas MacArthur and representatives from the other Allied countries were made, that is when the sun very literally came out.

Japan's Emperor Hirohito had ruled that they had gotten to the point where peace was better than continued bloodshed, and it was an uncomfortably close call. Operation Olympic — the invasion of Japan — had already been planned and scheduled for November, and it was predicted to be catastrophic, with casualties 10-fold what had been seen in Normandy. It wasn't the end of Allied presence in Japan, and according to the State Department's Office of the Historian, MacArthur found himself shifting from heading a plan to invade Japan to one to reform and rebuild it. With help from advisors from the Allied nations, the next seven years were spent stabilizing the economy, restructuring Japan's government, introducing new laws focusing on land reform and expansion of women's rights, and setting a clear path for the withdrawal of the Allied powers. The occupation lasted until 1952.

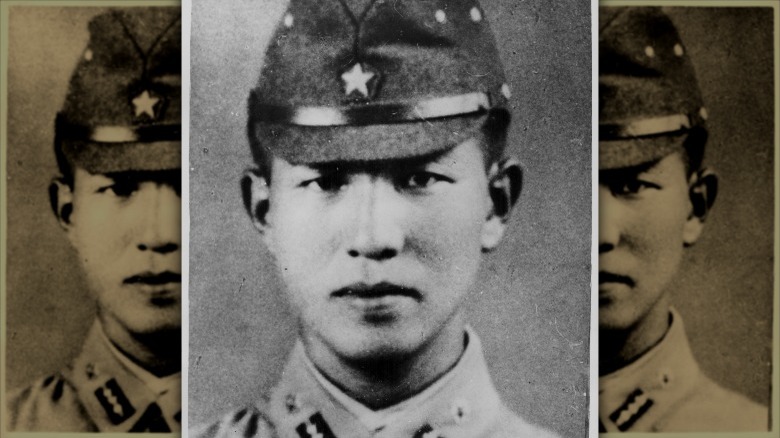

February and December 1974: The surrender of the last two Japanese soldiers

There's one last footnote to the war in the Pacific, and that's the story of the holdouts.

It was near the end of the war that Hiroo Onoda received his orders. In a 2010 ABC News interview (via BBC), he laid them out: "Every Japanese soldier was prepared for death, but as an intelligence officer I was ordered to conduct guerrilla warfare and not to die. I became an officer and I received an order. If I could not carry it out, I would feel shame." Carry it out, he did — until 1974, when he was finally able to be convinced that the war was over. According to the BBC, he resisted search parties and attempts to contact him — believing they were an Allied ploy — until his former commanding officer was flown to meet him where he was living in the jungles of the Philippines.

He wasn't the only one: Teruo Nakamura is believed to be the last of the holdouts, discovered living on the Indonesian island of Morotai a full 10 months after Hiroo Onoda. Nakamura was declared dead in 1944, but after spending 12 years with other Japanese holdouts, he headed off on his own to live on his own until he was rediscovered by the Japanese Embassy (via All That is Interesting).