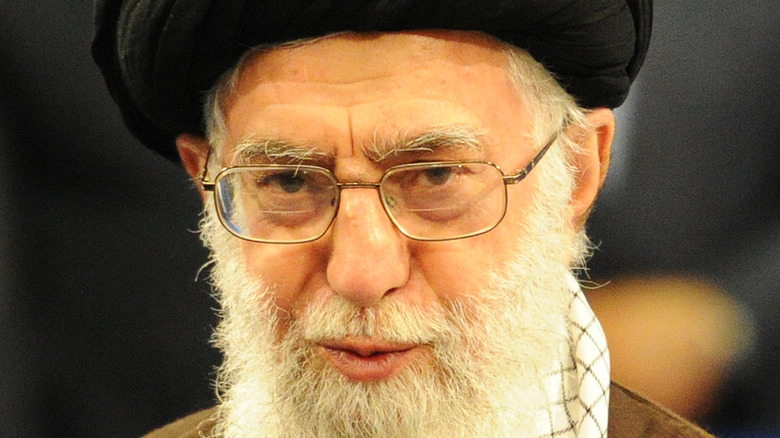

Facts About Iran's Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei

On September 16, 2022, the New York Times reported that Iran's supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, had cleared his working and public calendar after critical health issues left him bedridden. On that same day (per the Tablet), 22-year-old Mahsa Amini died while in the custody of Iran's morality police, having been beaten to death for an alleged violation of the country's regulation of women's hijabs. The government's attempted cover-up of the cause of death only gave more fuel to the outraged protesters who rose up in the wake of the tragedy. The size and determination of the protest movement coupled with Khamenei's ill health led some observers — like the Observer (via the Guardian) — to question the future of the Iranian regime.

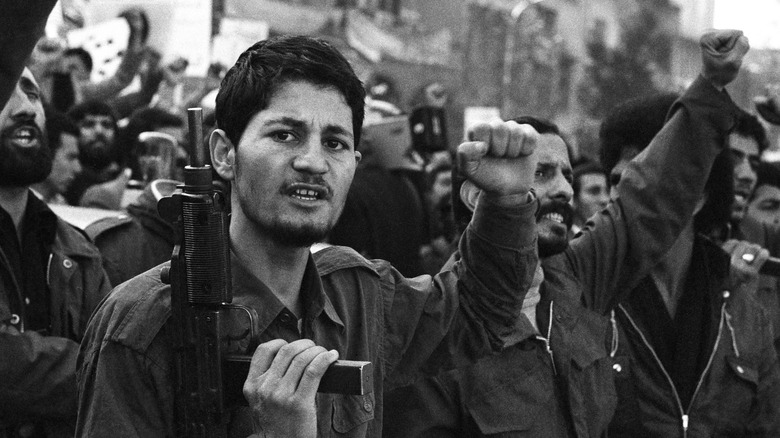

Others were less sure that meaningful change was in the cards. While noting similarities between the Amini protesters and the revolutionary movement Khamenei was a party to in 1979, historians told Reuters that the current regime is far more stable than the government of the shah Khamenei helped to overthrow. It makes greater use of brutal repression, projects strength, and has concentrated economic and military power among loyalists.

But even if Iran's government remains stable through the protests, and Khamenei makes a full recovery, he is 83, and as of 2022, no clear successor has emerged (per the Atlantic Council). Khamenei's death will mark significant changes for Iran and end the career of one of the Islamic Revolution's most notable characters.

His family has deep roots in Iran's religious community

Sayyid Ali Hosseini Khamenei was born in 1939 to Azerbaijani parents in Mashhad. John Murphy's biography, "Ali Khamenei," notes the future supreme leader had a spartan childhood. His father, the cleric Javad Khamenei, believed in limiting worldly distractions from God's teachings and kept a spare one-room household in a poor neighborhood. Khamenei's website (via Murphy) claims that his father was a recluse and that the family sometimes struggled to come up with enough to eat. Whenever callers would come on religious matters, the children, all eight of them, were sent to the basement.

But Ali Khamenei didn't quite lead a rags to riches story, making his way in the world without connections. Despite his poverty, Javad was a well-respected figure who led prayers at two mosques in Mashhad. According to the Institut Montaigne, the family is supposedly descended from Ali Zeyn-ol-Abedin, the fourth Imam of Shia Islam, letting Ali Khamenei claim to be part of a line stretching back to Muhammad himself. This base of legitimacy for his religious career was reinforced when two of his brothers also followed their father into the clergy. As a sign of their supposed descent from Muhammad, the three brothers wear black turbans.

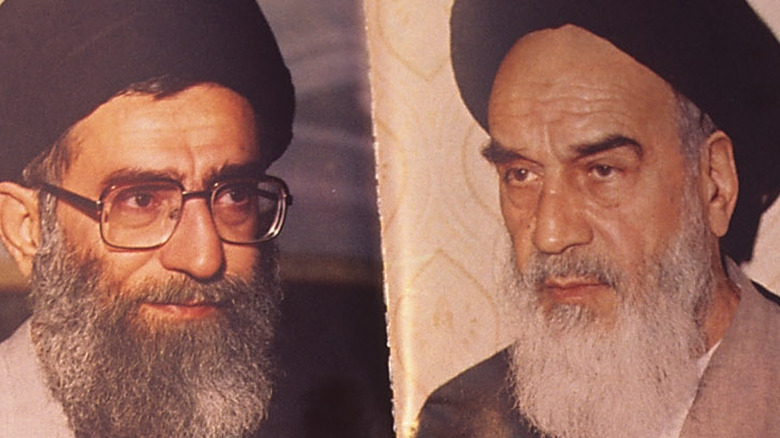

Ayatollah Khomeini was his teacher

As a prominent and pious cleric himself, Javad Khamenei wanted his sons to have a religious education. Ali Khamenei started school at age 4, in a Muslim school called a maktab, according to John Murphy's "Ali Khamenei." Maktabs received no support from the government under the shah and were intended as an alternative to the increasingly secular state education system. According to the BBC, Ali Khamenei became a cleric at 11, and his uniform brought him taunts on the streets of Mashhad.

Ali Khamenei persisted in his religious studies despite the mockery, looking to the example of his father. "He instilled in me the eagerness to embark on such a journey," he said, as related by the Islamic Center of London (via Murphy). He joined the Sulayman Khan Madrassa seminary in Mashhad and there first encountered political as well as spiritual fervor. While at the madrassa, Ali Khamenei heard a sermon by the revolutionary cleric Mutjaba Nawwab Safawi, who preached the overthrow of the shah and reinstating Islam's primacy in public and private affairs throughout Iran.

"It was at that very moment," Ali Khamenei claimed on his website (via Murphy), "because of Nawwab Safawi, that the consciousness of Islamic Revolutionary activism sparked inside me." After a brief stint studying in Najaf, Iraq, in 1957 (per the Institut Montaigne), his father urged him to return to Iran, and he found himself a student in Qom. There he took classes from, among others, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, future leader of the Iranian Revolution.

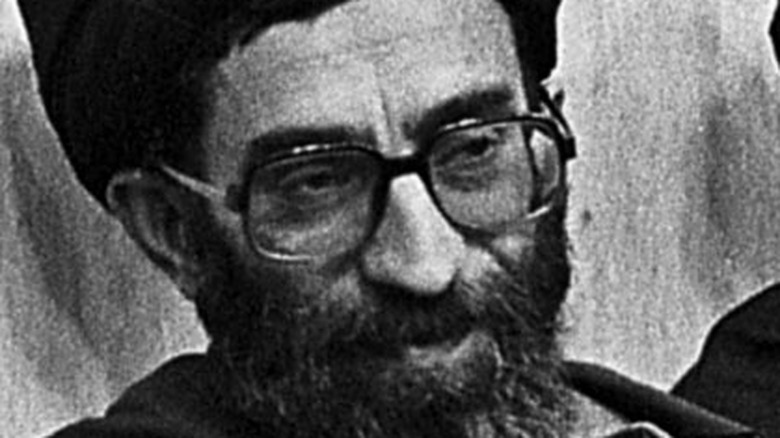

The unremarkable eccentric

Ali Khamenei was a dutiful son and a dedicated cleric, but no one who knew him as a young man imagined that he would become a power in Iranian politics, let alone the supreme leader. His nephew, Mahmood Mordankhani, told the BBC that Khamenei was a friendly and outgoing poetry lover. "Interestingly though," said Mordankhani, "in my memories he was unremarkable. He didn't stand out in any way. He was very ordinary."

Khamenei stood out a bit more when he studied in Qom, according to the Institut Montaigne. There, the extent of his political passions — and his habit of smoking a pipe — set him apart from his fellow clerics. His revolutionary activities, encouraged by the then-exiled Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, got him arrested six times. During one prison stint in the 1970s, he shared a cell with a communist activist named Houshang Asadi, according to the BBC. Like Mordankhani, he found Khamenei a pleasant fellow, with a good sense of humor (though not about sex). Asadi says that he never thought of Khamenei as a future leader.

Biographer Mehdi Khalaji has echoed these assessments of Khamenei as an ordinary man, crediting that quality with his success. But Asadi, whose communist movement was once allied with the Islamic revolutionaries against the shah, bemoans what Khamenei has become. "He changed from a man who fought for freedom to a dictator," he told the BBC. "Now Mr. Khamenei is more a dictator than a shah."

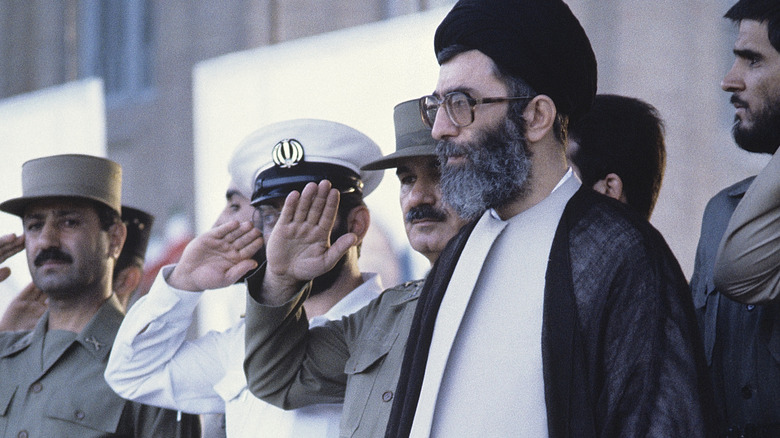

Ali Khamenei was a two-time president without power

Ali Khamenei was still serving three years of exile from the capital city of Tehran when the Iranian Revolution broke out (per the Institut Montaigne). Well-regarded and trusted by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the first supreme ruler of the new Islamic Republic of Iran, Khamenei was quick to advance in government. After stints as a Revolutionary Council member, an imam, and the deputy minister of defense, he was elected to the legislature as a member of the Islamic Republican Party (IRP), the political organ he had helped to found (per Britannica). Soon, he was president of Iran.

Khamenei was personally endorsed by Khomeini; according to John Murphy's "Ali Khameneni," the supreme leader valued Khamenei's loyalty over his previous inclination to separate the clergy and the presidency. In the October 1981 elections, Khamenei won with 95% of the vote. But the president of Iran was, at the time, a largely ceremonial office, notes Britannica. Significant political power belonged to the prime minister's office, and Khamenei regularly clashed with its incumbent, the more moderate Mir Hossein Mousavi.

Many of their disputes were resolved in Khamenei's favor by the Council of Guardians, and he was able to exert influence on Iranian foreign policy, as Murphy details. Still, Khamenei's direct access to power was limited until he succeeded Khomeini as supreme leader. Notably, the constitutional changes pushed through at the time of his ascension included the abolition of the premiership and the strengthening of the powers of the president.

His would-be assassins had other targets

The Islamic Republic of Iran did not rule uncontested in the years immediately following the Iranian Revolution. Many of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini's former allies, including left-wing and communist groups, found themselves betrayed and frozen out of power. In retaliation, the Mujahideen-e Khalq, described by John Murphy in "Ali Khamenei" as a Marxist opposition force, set off a campaign of terrorism against the leaders of the new theocratic government in the early '80s. Through targeted assassinations and bombs, they killed more than 70 figures of note, all of them allied with Khomeini. Victims included Mohammad Ali Rajai, president of Iran, and Mohammad Javad Bhonar, the prime minister.

Ali Khamenei was serving in the defense ministry at the time this assassination campaign was underway (per the Telegraph) and was soon to face voters in the presidential elections. As Murphy details, in June 1981, he spoke at a mosque in Tehran. There, a bomb hidden inside a tape recorder detonated. Khamenei's right arm was permanently paralyzed from the explosion, and his lungs and voice suffered damage as well. He spent the next few months in the hospital, where he received a personal message from Khomeini praising his loyalty. Khamenei took his survival as a sign from God that he was chosen for a great task; David Blair of the Telegraph wrote that it bred in Khamenei a stubborn and righteous streak.

His succession required constitutional revisions

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini died in 1989, leaving a power vacuum at the top of the Islamic Republic of Iran. For almost 10 years, according to John Murphy's "Ali Khamenei," Khomeini's intended successor had been assumed to be Hussein Ali Montazeri, a foreign policy hawk and a moderate on domestic freedoms. But Montazeri's willingness to criticize Khomeini — he once said that his regime's intelligence agencies were more brutal than the shah's — cost him the supreme leader's favor.

Khomeini's son and a prominent cleric both vouched that, on his deathbed, he had named Ali Khamenei his chosen successor as supreme leader. The council responsible for ongoing amendments to Iran's constitution (per Britannica) named him so only two days after Khomeini's death. Yet there were significant reservations about Khamenei's fitness for the job. He lacked the force of personality shown by Khomeini, and his religious education and accomplishments were seen as lightweight. There was also a legal barrier to Khamenei becoming supreme leader; the constitution required that the supreme leader be a grand ayatollah, and Khamenei had never become more than a cleric.

Khamenei was named an ayatollah, the requirements to be supreme leader were loosened, and prominent Iranian politicians — including future president Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani (per the Telegraph) — championed Khamenei's accession. Many probably thought he would be a more amenable leader than his predecessor — an assumption Khamenei was quick to disabuse them of, as he cut deals with hardliners to strengthen his power.

He has a long relationship with the Revolutionary Guard

How does a theocrat stay in power? Bloodlines, quotes from scripture, and appeals to divine will may help establish legitimacy among believers. But when the religious carrot fails, a military stick will suffice. Since his elevation to supreme leader in 1989, Ali Khamenei has been supported by Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). The association predates Khamenei's current office; per Britannica, he was at one time commander of the IRGC.

Despite being their one-time leader, the IRGC viewed Khamenei with suspicion throughout the 1980s, according to Foreign Policy; they perceived him as too moderate. Distrust ran so high at one point that Khamenei was denied the chance to visit the front lines of the Iran-Iraq War.

By 1989, however, Khamenei was in line to become the next supreme leader of Iran, on dubious legal grounds and without the full confidence of regime elders. To ensure his position, he negotiated a deal with the IRGC, who found themselves struggling for a purpose after the Iran-Iraq War: If they accepted him as supreme leader, Khamenei would grant the IRGC a free hand in political matters. They could be first in line for funding, mount their own independent intelligence agency, veto foreign policy initiatives, and take a significant piece of the Iranian economy. The IRGC accepted, and they've shored up Khamenei's regime ever since.

He's picked up a lot of wealth over the years

The example of simple living set by his father has stayed with Ali Khamenei throughout his life. He has spoken (via John Murphy's "Ali Khamenei") about growing up in a one-bedroom house, making do with bread and raisins for dinner, and making do with clothes sewn out of his father's hand-me-downs. Public assumption in Iran is that Khamenei leads his own family in a similarly spartan lifestyle to this day.

But if Khamenei does live in such a minimalist fashion, it's by choice. As supreme leader of Iran, he has access to considerable wealth. As of 2013, according to Reuters (via the Telegraph), he exercised control of an over $95 billion portfolio, considerably more than what the shah ever had access to. A large piece of that wealth came from property seizures by the Headquarters for Executing the Order of the Imam (Setad), an organization under Khamenei's direct control responsible for managing the assets of Iran's leadership. Its worth in 2013 was 40% higher than oil revenues for the same year.

Reuters found scant evidence that Khamenei made personal use of the wealth generated by Setad, though Iranian defectors once told the Telegraph that he leads a more lavish lifestyle than he lets on. Setad's financial seizures seem designed more to solidify Khamenei's power and win him more independence and control of Iran's political class. Such seizures are also used as a tool against the oppressed Bahai minority.

Ali Khamenei clashed often with Mahmoud Ahmadinejad

While the brutality evidenced by Mahsa Amini's death in police custody makes it difficult to believe, Ali Khamenei has been viewed within Iran as a moderate among religious leaders at different points in his career. His perceived pragmatism and moderation was what made him suspect as a potential supreme leader to many hardliners in 1989, according to Foreign Policy, and as recently as 2007, Newsweek quoted sources close to Khamenei on his closeted liberalism, constrained only by the practical realities of working within a conservative religious state. "If it were up to him," said one source, "he would allow much more freedom in the country than we have now."

Such alleged sentiments were used to contrast Khamenei with Iran's then-president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Ahmadinejad had been involved in the seizure of the United States embassy in 1979 and was a solidly conservative and reactionary figure by the time he won the presidency. Over the years, he developed a penchant for confrontation. The BBC named a slew of sparring partners for him, foreign and domestic, with Khamenei topping the list.

Khamenei initially supported Ahmadinejad's rise to power. Their clashes may have had less to do with Ahmadinejad's conservatism than the stumbles Iran's economy took under his presidency. Ahmadinejad was also perceived to be cultivating an independent power base, something Khamenei wasn't about to abide. By the end of the president's term, the supreme leader was overruling key decisions and leaving him to sulk.

Did he authorize the assassination of an ambassador?

In 2011, an Iranian-American, Manssor Arbabsiar, made a $100,000 down payment to what he believed was a Mexican cartel member. Per the Los Angeles Times, the payment was an advance on a $1.5 million fee to assassinate the Saudi ambassador to the United States. Arbabsiar's contact turned out to be a DEA agent, who recorded Arbabsair insisting that the ambassador should die in a bombing no matter the collateral damage. After foiling the scheme, U.S. officials claimed that Arbabsiar was working for the Quds Force, a unit of the Iranian military, and that the plot would have had the sign-off of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei.

Officials argued that only Khamenei could have approved an operation that targeted such a high-profile figure. Iran, of course, denied the accusation. But independent intelligence agencies from the U.S. government also called the idea of Khamenei approving such an operation into question. Per the Guardian, attacking an ambassador on American soil would represent a massive escalation that risked fierce retaliation from America and Saudi Arabia, something Khamenei characteristically sought to avoid. The idea that he, or the Quds Force, would entrust a large sum of money and a dangerous terrorist plot to a Texan and drug cartel members they didn't know was also seen as suspect. Arbabsiar's own statements cast doubt that he had meaningful connections to the Iranian government, and even U.S. intelligence had to concede that their case wasn't airtight.

His health has been in doubt for some time

Ali Khamenei's September 2022 retreat from public events due to his health is only the latest such episode he's endured in recent years. As early as 2007, according to Hooman Majd's "The Ayatollah Begs to Differ: The Paradox of Modern Iran," Western media began reporting on a possible decline in Khamenei's condition. Iran dismissed such claims as rumors designed to demoralize the country, but Majd felt that photos taken of Khamenei at the time showed him noticeably weakened.

In 2014, his health was in the news again. The New York Times reported that Khamenei underwent prostate surgery on September 8. He announced that he would need an operation himself on state television, and his doctors insisted that it was a routine procedure. But the surgery fed years of speculation that the supreme leader of Iran suffered from prostate cancer.

Khamenei's 2022 health woes included another surgery, this time for a bowel obstruction (per the Times), and he was confined to his bed under doctors' supervision. He was reportedly too weak even to sit up. Among the functions that needed to be canceled at the time was a meeting between Khamenei and the Assembly of Experts, the council that will need to determine his replacement when he dies.