World War II Allied Home Front Timeline Explained

The announcement made to the British people telling them that their country was officially at war with Adolf Hitler's Nazi Germany lasted just five minutes. Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain simply said, "This country is at war with Germany," apologized for what he saw as a personal failure to keep Europe in a state of something that wasn't quite war, but honestly wasn't even close to peace, and signed off (via the BBC).

Throughout the 1930s, Britain and France had both tried to avert a repeat of the Great War, a tragedy of epic proportions that both countries — along with Germany — were still recovering from. To those ends, the Imperial War Museums say that they felt little choice but to operate under a policy of appeasement: Hitler could expand his territory within reason, but Poland was off-limits ... until it wasn't, and the next war was on.

The toll in human lives can only be estimated, says The National WWII Museum: Somewhere around 15 million soldiers died on the front lines, but civilian deaths were even higher. Some sources claim 45 million died, while others say that 50 million perished just in China. Life on the homefront was hard, too, so let's take a look at what was going on in the U.S. and Britain while millions died ... sometimes, just a stone's throw away.

November 1938: Gallup polls America

Here's some important context for America during the war, and it comes courtesy of Gallup. In November of 1938, Gallup polled U.S. residents on the events of Kristallnacht, the nationwide attack on Germany's Jews. While they agreed — by a margin of 94% — that it was a bad thing, only 21% said that America should consider opening some doors for refugees.

And here's where the general climate gets even more telling. Not only were fringe groups — like the Nazi Stormtrooper-esque organization of William Dudley Pelley's Silver Legion of America — forming to celebrate Nazi ideals, but another Gallup poll suggested Americans knew exactly who to blame for it all: The Jews. A whopping 54% replied that the persecution they suffered was "partly their own fault," and at the same time, 67% condemned the idea that even child refugees should be allowed into the country.

Fast forward to 1944, and less than 25% of Americans who responded to another poll said they could believe more than a million Jews had been murdered. Many suggested the numbers were exaggerated, and couldn't possibly be higher than 100,000. The real number was more than 5 million.

Aug. 31, 1939: Operation Pied Piper announced

With the mass growth of European cities and the development of aerial warfare came a new worry: What would happen when planes — and the bombs they carried — were able to reach deep into enemy airspace, and target major population centers? Britain's government had been preparing evacuation plans for such an eventuality for a long time — and when Operation Pied Piper was announced, the memories of WWI bombings by German zeppelins — and the 1,239 deaths they caused — were still fresh.

Britain, says The History Press, was broken up into zones including Evacuation, where high-risk civilians and children would be moved out of densely populated areas, and Reception, which were the areas deemed appropriate for hosting the evacuees. The whole scheme had been worked out as a contingency plan in 1938, and after an Aug. 31 announcement, the first children queued at their schools on Sept. 1, suitcases in hand.

In just three days, around 1.5 million children and pregnant women were evacuated under the supervision of 17,000 volunteers. Families that participated did so voluntarily, not knowing where their children were sent until they were mailed a postcard with the details. Although some returned in the relatively quiet months at the start of the war, many didn't return until the end: They were as many as five years older, completely different people, but alive.

Sept. 1, 1939: Britain introduces blackout rules

One of the biggest changes to daily life — the blackout — was introduced before Britain was officially at war. The reason was simple: any light could make cities a target for enemy planes. The Imperial War Museums say that even early rules were strict, forbidding even the lighting of a match outside.

Life in complete darkness wasn't easy, and it's estimated that one in five people had suffered a blackout-related injury by the start of 1942. 1940 saw the most deaths — with 9,196, according to Parliament — and journalist Mea Allan wrote (via The Guardian): "... it was a fearful portent of what war was to be. We had not thought that we would have to fight in darkness, or that light would be our enemy."

Cities had been practicing blackout drills for more than a year at the time they became mandatory: Still, hundreds of people were killed in the streets, travel was made more difficult by unlit train cars and unlit bus numbers, dockworkers fell into the water and drowned when no one could see to rescue them. Looting and mugging were on the rise, factory work became literally suffocating, and by 1941, doctors were diagnosing a seasonal affective disorder-like condition called blackout anaemia. Still, the lights were out and would remain out until April 23, 1945.

Sept. 3, 1939: The British dog and cat massacre

It started, says the BBC, during the previous summer. War had seemed pretty inevitable by that point, and as a part of their preparatory literature, the National Air Raid Precautions Animal Committee published a pamphlet called "Air Raid Precautions for Animals." It suggested things like having city-dwellers send their pets to the countryside for their own safety, and it also added, "If you cannot place them ... it really is kindest to have them destroyed."

And that's what people did on a shocking scale. According to the Independent, around half a million cats and dogs were buried in a mass grave in Ilford. More were cremated — so many that the crematoriums couldn't handle the influx, and bodies piled up in the streets outside of veterinary clinics. It's unclear just how many were euthanized by owners fearing bombing raids and food shortages, but estimates suggest casualties were as high as 750,000 ... in just the first week after Britain's declaration of war.

Many animal charities scrambled to try to tell pet owners not to overact, but it was a message that fell on deaf — and panicked — ears. Even as the nation rallied to war, organizations like the Battersea Dogs and Cats rallied to the rescue of Britain's pets — Battersea alone saved 140,000 pets.

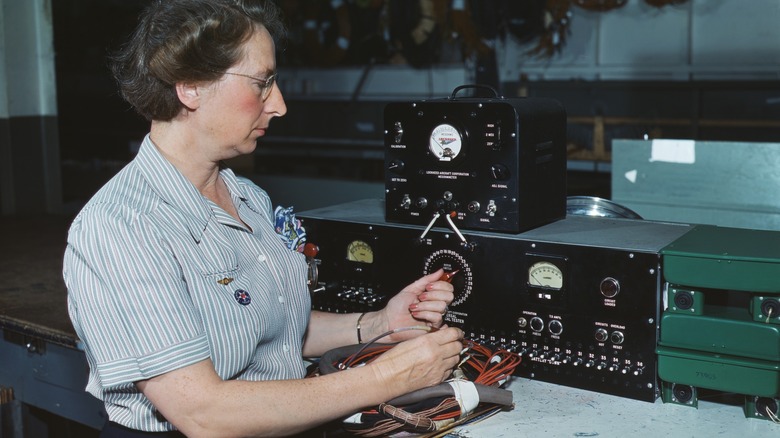

January 1940: Formation of the American Women's Voluntary Services

The U.S. wouldn't join the war until after the Dec. 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, but preparations started long before then — and when a group of wealthy women started the American Women's Voluntary Services based on their British counterparts, the Museum of Textile Services says they were viewed as unnecessarily alarmist.

Still, many saw the writing on the wall, and by the time the U.S. entered the fray, they had recruited around 18,000 volunteers. Over the next few years, that would increase to around 325,000 women signing up to do essential tasks on the homefront, including things like aerial photography, driving trucks, delivering messages and supplies, filling disaster response teams, and selling war bonds. Rutgers says that at its height, the AWS was the nation's largest service organization, and it counted some famous names among the roster.

When Betty White passed away in 2021, the U.S. Army was among those who paid tribute to her, remembering her time with the AWVS. She, says People, had a dual role: Even as she was tasked with driving trucks of military supplies to California barracks, the other part of her job was decidedly less militaristic — she was one of the women who regularly attended dances held for departing soldiers as a part of her service.

Jan. 8, 1940: Rationing in the U.K. starts

Shortages during the war were a major concern, and in order to try to make sure everyone at least had what they needed to survive, Britain established a system for rationing just a few months after they issued a formal declaration of war. According to the Imperial War Museums, rationing was the responsibility of the "1984"-sounding Ministry of Food, and it was pretty dire stuff.

While some things — like vegetables — weren't rationed, most staple foods were. Households registered with grocers and used coupons from ration books to buy what they were allotted for the week, and it wasn't much. According to Historic UK, a week's worth of food for an adult included 4 ounces each of bacon or ham, margarine, and cooking fat, another type of meat in an amount equivalent to two pork chops, 2 ounces each of butter, cheese, and tea, 3 pints of milk, 8 ounces of sugar, and one egg. Every two months, a person could get a pound of preserves, and once a month, they were entitled to purchase 12 ounces of sweets.

Supplemental foods — like cereals and tinned food — were purchased via a point system or grown in a home's own "Victory garden," so it was up to each house to figure out what was going to go the farthest for them.

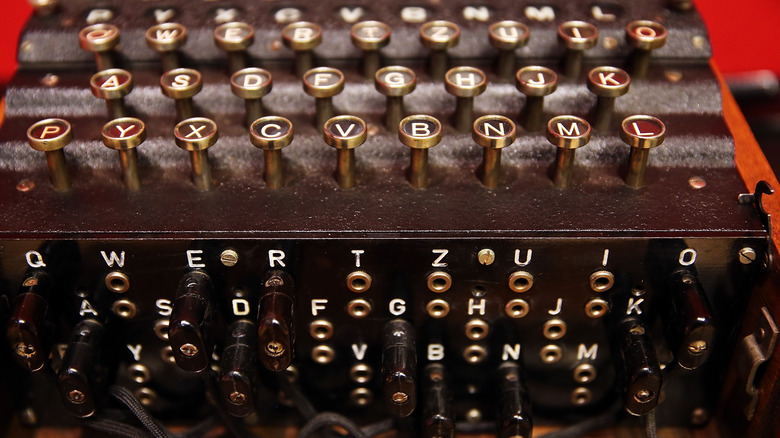

Mar. 14, 1940: Alan Turing installs the first Bombe at Bletchley Park

Alan Turing is famously credited with breaking the German Enigma code and allowing the Allies to read "top secret" messages. It was a huge deal: According to the BBC, Churchill once commented that the only things that really had him worried were the German U-boats that prowled the Atlantic and sank supply ships heading to Britain. With the codes broken, their positions and orders were revealed to the Allies, who could avoid the majority of the German boats.

Interestingly, though, it wasn't Turing who first broke Enigma — it was the Polish, way back in the 1920s. The National Museum of Computing explains the problem, though, which was that the code had gotten more complicated, and the Polish machine for decrypting it — the Bomba — was obsolete by WWII.

What Turing did was mechanize the process, update the technique, and create the Bombe. He did it incredibly quickly, too. After starting work at Bletchley Park in September of 1939, he installed the first Bombe prototype on March 14, 1940. This prototype was the first of what would ultimately turn into 211 code-breaking machines, starting with an even more accurate Turing-Welchman Bombe that became operational in August of the same year, and was called Agnus Dei, or Agnes. Turing and his team's Bombes are credited with saving countless Allied lives.

Sept. 7, 1940: The Blitz

It's difficult to imagine the terror of the Blitz: According to The Imperial War Museums, the bombing of London by German planes started on Sept. 7, 1940, and continued without reprieve for the next 57 nights. Other air raids targeted other cities across the country: Coventry was targeted with more than 30,000 bombs on a single November night in 1940, Birmingham was the target on multiple nights between August and November, and cities including Bristol, Southampton, Manchester, Liverpool, and Sheffield — along with Welsh cities like Cardiff — were devastated by German attacks from above.

The worst night in London was that of May 10-11, 1940. According to the Royal Air Force Museum, the city was hit by 571 sorties dropping 711 tons of bombs, along with 86,173 incendiaries. To give an idea of how much of the city was destroyed, the damage was twice what was done during the infamous Great Fire of London.

Stories are heartbreaking, like the one from Ruth Blair (via Liverpool Museums). She recalled her father helping her neighbor search for his family — including his wife, Amy, and their sons, aged 4, 5, and 11 — after their house was hit: "The first thing Mr. Jones found was his son's Boy Scout Bugle. All four were sadly dead. With tears streaming down his face, he turned to my father and congratulated him on our survival. The memory of this never left my father."

In nine months, more than 43,000 civilians died.

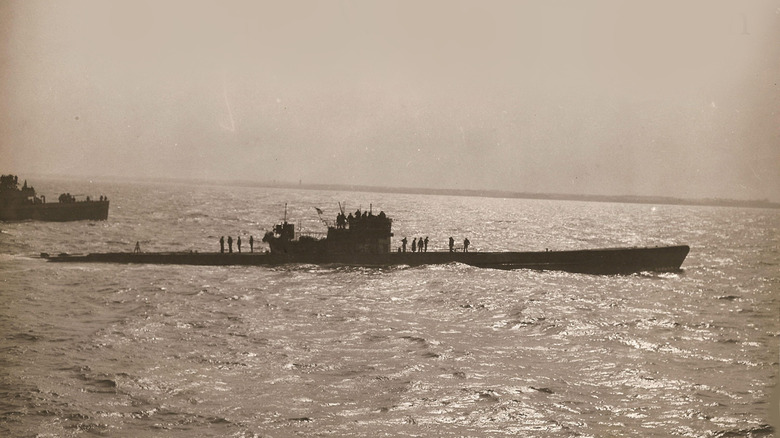

Jan. 1942: German and Japanese U-Boats start attacking ships off the U.S. coasts

The U.S. officially entered the war after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, and in January, German U-boats had already moved into its waters. Ed Offley is the author of "The Burning Shore," and told The Washington Post that this little-known chapter of the war brought death and devastation right to America's doorstep.

Starting in January, Offley says "the U-boats rampaged practically unopposed along the East Coast, sinking 226 Allied merchant ships totaling 1,251,650 gross registered tons" by June of the same year. On the West Coast, Japanese subs were doing the same thing — one incident that targeted Santa Barbara resulted in mass panic, deaths, and a swath of destruction.

The National Museum of the Air Force says that both they and the Navy were ill-equipped to deal with the threat, and as a result, the Germans pretty much owned the coastline. Things were so dire that civilian planes were requisitioned, equipped with bombs, and sent out against the U-boats ... until the Navy was prepared to take over entirely in late 1943.

Feb. 19, 1942: Executive Order 9066 begins American internment camps

After Pearl Harbor and amid continued attacks on the West Coast, the 120,000-odd Japanese Americans living on U.S. soil found themselves in a terrible position. Most — about two-thirds, according to The National WWII Museum — were citizens who had been born in the U.S. and spent their entire lives on U.S. soil, but when FDR signed Executive Order 9066 on Feb. 19, 1942 ... it didn't matter.

The order didn't precisely call for moving anyone of Japanese ancestry to internment camps, but that's ultimately what happened. The order gave the military permission to create exclusion zones, which was then used to order the removal of Japanese-American families from huge areas of the country. (It's also worth mentioning that not everyone was on board with this, with some governmental high-ups, like Secretary of War Henry Stimson, going so far as to suggest this whole thing was illegal.)

But with no one wanting to take the displaced families — and some, like Idaho's Attorney General, loudly proclaiming "All Japanese [should] be put in concentration camps for the remainder of the war," — the War Relocation Authority established a series of Army barracks-style camps to house the displaced. The National Archives says that from March to August, 112,000 people (including 70,000 American citizens) were processed through the system.

April, 1942: Life-term prisoners try to kick-start their draft

Wartime patriotism has been well-documented in the form of everything from the sales of war bonds to the Rosie the Riveters who left home and went to work in factories across the country. Less well-known is a more unlikely source of patriotism and support for the war effort: U.S. prisons. Even as many factories retooled their production lines to supply the Allied war machine, prisons were doing the same thing. According to research done by Seton Hall University, some prison production centers were revamped to provide materials for the war, and interestingly, some inmates were appealing to get in on the action ... overseas.

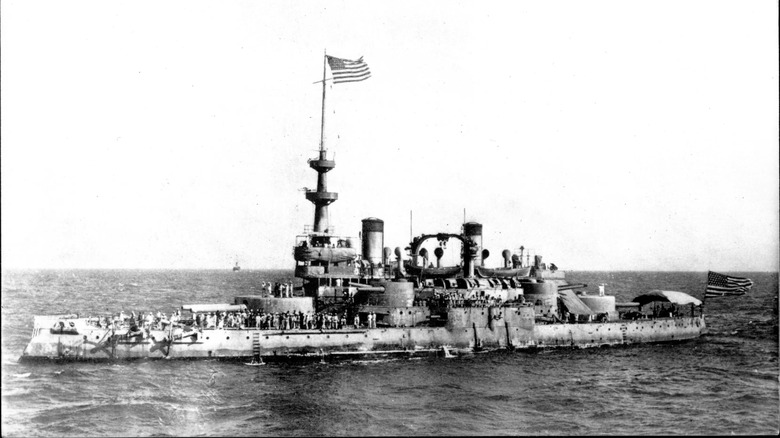

On April 20, 1942, The New York Times reported that inmates from an Oklahoma penitentiary had petitioned FDR with an interesting proposal: They'd heard that the long-retired battleship the Oregon (pictured) was going to be outfitted and sent into the Pacific on a suicide mission to take out as many Japanese craft as they could before they were taken down — and they wanted to crew the ship.

It wouldn't happen: The History Cooperative says the turn-of-the-century Oregon was used briefly to transport supplies until it was caught in a typhoon in Guam and, after the war, was sold for scrap. Still, the appeal wasn't alone, and state penitentiaries across the country set up (weapons-free) training facilities where inmates could train and be prepared to immediately be drafted if the need arose.

May 1942: Rationing begins in the U.S.

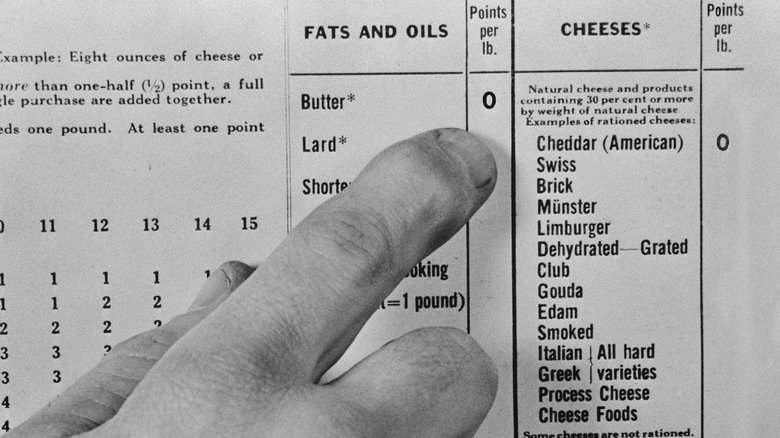

More than two years after the U.K. established a system of food rationing, the U.S. did the same thing. Although History says that things like price and quantity limits were officially in place the month after Pearl Harbor, it wasn't until spring that sugar became the first commodity that couldn't be purchased without tickets. That was followed by coffee, and it wasn't until March of the following year that processed foods, meat, milk, cheese, and other staples were added to the list.

In addition to coupons, some foods were purchased through a point system — a necessity for food stores that were unreliable and ever-changing.

Roosevelt's government had been planning ahead for the inevitability of rationing for some time, as the overseeing Office of Price Administration had been created in August of 1941. Rationed items didn't stop at food, either, and as the war dragged on, the National Park Service notes that things like shoes, fuel oil and gasoline, firewood, nylon, and even cars were also rationed.

July, 1942: Arrest of Herbert Karl Friedrich Bahr, on suspicion of spying

According to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, the U.S. claimed to be organizing a place for Jewish refugees as early as 1938, then promptly did not do much at all. The New York Times says that in all the war years, only a single refugee camp was ever built in the U.S., and a big reason for the pushback against allowing refugees into the states was the fear that it would allow Nazi spies a way into the country.

There was one particular incident that gave protesters credibility, and that was the 1942 arrest of Herbert Karl Friedrich Bahr. The Smithsonian says that the 28-year-old German entered the U.S. in the summer of 1942 after sailing from Europe on the SS Drottningholm, but not for the first time. The German-born Bahr had studied in the U.S., gotten his citizenship, and returned to Germany for further schooling. When war broke out, he fled back to the States, claiming he was trying to escape Nazi violence. After an interview with the FBI started poking holes in his story, he was arrested on espionage charges: The New York Times says that when his mother was notified, she said, "We have lost Karl. We have lost him forever."

Bahr was sentenced to 30 years (although there was a major push to give him the death penalty), and his story was used to help stop Jewish refugees from being allowed to enter the U.S.

Aug. 13, 1942: Establishment of the Manhattan Project

The dropping of the atomic bombs would be two of the most infamous moments of the war, and it started on Aug. 13, 1942. That, says the Atomic Heritage Foundation, is when the Manhattan Project came into being. In December, FDR funneled a whopping $500 million into the project. Adjusted for inflation, that's the equivalent of about $8.6 billion today. Originally based in Manhattan, it would move to Washington D.C., and ultimately be made up of satellite sites, including Los Alamos, New Mexico, and Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

History has been written, but if some Manhattan Project scientists had been heard, it might have gone differently. Things moved quickly: The bomb was tested at the Trinity site on July 16, 1945, and was dropped on Hiroshima on Aug. 6. In the meantime, 155 scientists signed Leo Szilard's petition asking the president to drop the bomb somewhere it could make a point ... but not kill people. Truman never got the petition, and it's been well-documented how it all went down.

Evelyne Litz worked on the project at Los Alamos and recalled the difference between VE-Day and VJ-Day. While the end of the war in Europe was marked by celebrations and wine, the world post-bomb was very different. "VE-Day, wonderful," she recalled. "The day the bomb was dropped there was no hilarity on the hill. None of our friends got together; we were very solemn."

Mar. 3, 1943: Bethnal Green Tube disaster

The events of March 3, 1943, set two awful records: Not only was the tragedy at Bethnal Green result in the highest casualties of any single event in London's Underground, but Historic UK says it was also the deadliest civilian disaster of the war.

The Underground did double duty during the war, serving both as transport and as bomb shelters. Countless people would head there when the air raid sirens would go off, and it had become a common occurrence. Things were different on that March afternoon, though: When locals responded to the air raid sirens by heading to the Tube station, they found it closed except for a single door. Then, when the anti-aircraft guns being tested at a nearby park started to go off, chaos ensued. Joan Martin was a doctor working at the nearby Queen Elizabeth Hospital for Children and recalled (via the BBC) being told to prep for receiving 30 people who had fainted. "We had hardly finished changing the beds before the first wet, mauve body was carried into the hospital."

At the bottom of the stairs, three people — a woman, her child, and an elderly man — had fallen. People behind them had no idea what had happened and continued trying to push and shove their way in. By the time it was over, 173 were dead, and the government made a push to cover it up in hopes of preventing another panic in a city already stretched to breaking.

November 1943: English villages are seized for D-Day training

In Nov. of 1943, the residents of the 102-home village of Tyneham were given devastating news: They had 28 days to pack, because their village now belonged to the military. All residents left, and when they did, they left a note on the door of the church (pictured). It read (via Country Life): "We have given up our homes ... to help win the war to keep men free. We will return one day, and thank you for treating the village kindly."

The same thing happened in the village of Imber, about 60 miles away. Both villages were turned over to the military to train the troops that were sent to Normandy as a part of the D-Day invasion, and according to the Salisbury Journal, the street fighting that American troops were supposed to learn in Imber never happened. Instead, the village remained empty, with the military citing dangers from nearby shell impacts.

Although residents were promised they'd be allowed to return home, none ever did. Imber remained under the control of the Ministry of Defense, which used it to train soldiers that would be dispatched to Northern Ireland in the decades after the war. Tyneham remains empty, in spite of repeated appeals from residents like John Gould, who, in 1974, wrote to the Prime Minister (via the BBC): "Tyneham to me is the most beautiful place in the world ... I want to go home."

Aug. 5, 1944: The only Jewish refugees allowed in the U.S. arrive in New York

The Allies may have been willing to send soldiers to the front lines to fight and die by the hundreds of thousands, but when it came time to give shelter to refugees, their record was less stellar. According to The New York Times, there was precisely one refugee camp set up in the continental U.S., and it was a converted military base in Oswego, New York. Exactly 982 refugees were allowed in, and after being stripped, sprayed with DDT, and herded onto a train, they made it to the camp on Aug. 5, 1944. Ban Alalouf was three years old, and recalled the panic of seeing the fenced-off camp from the train: "Obviously, everyone thought it was a concentration camp."

The camp was supposed to be the first, not the only. But convincing anti-immigration Congressmen to open U.S. doors to those persecuted — and often executed — minorities of Europe was easier said than done. Led by North Carolina senator Robert R. Reynolds, there was a crusade of "Let's save America for Americans," and even a suggestion of building a wall around the country.

The result was that not only was Oswego the only refugee camp, but amid fears that the truth would see the development of public pressure to admit more refugees, the U.S. State Department renewed efforts to keep the extent of the Nazis' actions on the down-low.

May 5, 1945: Japanese weapons kill American civilians on U.S. soil

Throughout the entire war, there's one incident that ended with American civilians being killed on American soil. Those civilians were Elyse Mitchell, the wife of an Oregon reverend, their unborn child, and a group of children from their town's Sunday school: 14-year-old Dick Patzke, 13-year-olds Eddie Engen, Jay Gifford, and Joan Patzke, and 11-year-old Sherman Shoemaker.

In the months leading up to that tragic day, those living around Oregon's Gearhart Mountain had witnessed strange things in the sky. It wasn't their imaginations: They were balloons, launched by Japan and sent floating toward the U.S. on the jet stream, in hopes of causing some mass destruction.

The Smithsonian says that about a thousand of the balloons made it across the ocean, although the government silenced any chatter about them in the hopes that Japan would stop making and launching them. They did — not long before the deadly incident in Oregon. Public warnings were issued in the weeks after the death of Mitchell and the picnicking children, but no other casualties were reported. Years later, one of the many girls conscripted to help build the balloons would be put in touch with the family members who had lost their loved ones: A small group of schoolgirls-turned-bomb-builders expressed their sorrow by folding and sending 1,000 paper cranes to the families.

July 8, 1945: The Utah POW camp massacre

World War II left the deep scars of trauma across an entire generation, and that was perhaps no more highly visible than in what The Salt Lake Tribune calls the "worst mass murder at a POW camp in U.S. history." And there were a lot of camps — History Collection says that the U.S. was home to around 400,000 German and Italian POWs spread out across about 700 locations (like the one pictured).

It was at a camp in Utah, however, that on July 8, 1945, Pvt. Clarence V. Bertucci fired 250 rounds into a series of tents housing 250 German POWs, killing nine and wounding 19. Bertucci, it turned out, had enlisted, been sent to the U.K., and returned stateside after being court-martialed twice for disciplinary problems. Still, he had been fond of saying that he'd been unfairly treated, and telling locals that he was still going to have his turn to see combat. Historian Pat Bagley wrote for the Tribune, "The wounded were taken to the Salina hospital, where it's remembered that blood flowed out of the front door. One prisoner, nearly cut in half, would survive six hours."

The war in Europe had ended two months prior to the shooting. Bertucci was later committed to an asylum in New York, and died in 1969. The dead were buried in the U.S., and the wounded eventually returned to Germany.