David Jewitt And Jane Luu's Exploration Of The Kuiper Belt Explained

The history of exploration is littered with examples of the intrepid searching the unknown for what they believe must be true. Equipped with the knowledge that the Earth was round, Christopher Columbus sailed west, reasoning that he must eventually reach Asia. Although Columbus vastly underestimated the size of the Earth, he was right that trans-Atlantic travel was viable.

In the 19th century, scientists armed with the robust celestial mechanics of Johannes Kepler and Isaac Newton predicted the existence of Neptune. William Herschel discovered Uranus in 1781, and it was found that it didn't precisely obey the natural laws of gravitation, sometimes traveling in its orbit too fast, sometimes too slow (via Starts With A Bang). To account for this discrepancy, an eighth planet was postulated, and in 1846, Urbain Le Verrier accurately predicted its location, leading to the discovery of Neptune less than a month later.

Following the discovery of Pluto in 1930, many astronomers predicted it would be the first of many trans-Neptunian objects discovered (via Scientific American). Sixty years later, nothing had been discovered. Besides Pluto, the outer solar system (in contrast to the asteroids and comets of the inner solar system) was oddly empty. Intrigued, David Jewitt and Jane Luu spent six years methodically surveying the night sky, looking for anything in the empty reaches of space.

On the origins of comets

Comets have been around since the dawn of the solar system, so we've been observing them for a long time. For most of human history, comets were considered an evil omen. It wasn't until the 17th century — when the likes of Isaac Newton and Edmond Halley applied their minds to the matter — that comets entered the realm of quantifiable phenomena (via European Southern Observatory). Broadly speaking, comets can be placed in two general categories. The short-period comets take fewer than 200 years to orbit the sun and usually do so in roughly the same plane as the rest of the planets. The long-period comets orbit the sun over the course of 200 or more years (up to 250,000 in some cases) and have orbital planes that can be highly inclined (via Las Cumbres Observatory).

Some comets we know the origins of. The Jupiter family comets, for example, have orbits that can extend a bit past Jupiter and take about 20 years to make a round trip around the sun. Per NASA, in the 1950s, Jan Oort theorized that the long-period comets came from a spherical reservoir of icy objects at the edge of the solar system 2,000 AU away (1 AU is the distance from the Earth to the sun). The short-period comets were thought to come from much closer, around the distance of Pluto, or 30 AU. According to theory, Pluto should have been one of many objects at that distance, but as far as we knew, everything beyond was empty.

Putting together a theory

Soon after the discovery of Pluto, astronomers began speculating that Pluto would be the harbinger of more trans-Neptunian discoveries. In 1943, Kenneth Edgeworth posited that in the early days of the solar system, the protoplanetary disc surrounding the sun would be thicker towards the center and thinner around the edges. According to him, the higher density of mass in the center led to the planets, but due to the scarcity of matter at the edges, it would leave a vast area of smaller bodies orbiting the sun (via "The Solar System Beyond Neptune").

A counterargument was put forward by Gerard Kuiper (rhymes with viper) in 1951 (via Astronomy Trek). Kuiper believed that Pluto was as large as Earth (it's not even close) and that while there might have been a ring of icy remnants from the early solar system for a time, the entire area would have been long since swept clean by Pluto. By the 1980s, our conception of a cometary nursery began to coalesce. Julio Fernández was the first to accurately predict the form this belt would take in 1980 (via Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society). Toward the end of the decade, a name was given to this then-theoretical region. It wasn't named for Edgeworth, who first applied scientific principles to the idea of it, nor Fernández, who first described the form it should take. Rather it was named for the man who said it shouldn't exist at all: Kuiper (via Astronomy).

Searching for the belt

None of that mattered to David Jewitt. He was intrigued by the fact that since the discovery of Pluto in 1930, only one non-planetary object had been discovered beyond the orbit of Saturn. Between the sun and Jupiter are uncountable asteroids and comets, but for most of the 20th century, as far as we knew, the outer solar system was barren (via Astronomy Beat). Setting aside the possibility that the region beyond Saturn was devoid of rocky or icy bodies, Jewitt and graduate student Jane Luu began scouring the sky, looking for anything that lay beyond our ringed neighbor. They called their search the "slow-moving object survey" because the celestial objects they were looking for would appear to move across the sky very slowly due to their distance (via Serious Science).

Their search began in 1986 when they compared both photographic plates and digital images. Photographic plates are a physical and mental burden to compare, so the team quickly switched to an entirely digital survey, which allowed them to quickly compare two images by "blinking" back and forth between the pair, looking for any changes (per Astronomy Beat). Their breakthrough came in 1992 when they spotted a faint object over 10 billion miles further away than Pluto, proving that the Kuiper Belt was more than just a theory.

To be or not to be a planet

Since David Jewitt and Jane Luu's discovery, astronomers have discovered over 2,000 objects orbiting the sun in the icy reaches beyond Neptune (via NASA). But most scientists believe that that number is only scratching the surface of what's out there. It's estimated that there are around 100,000 objects at least as big as the one Jewitt and Luu discovered. The reason we've only found 2% of them is because the Kuiper Belt is huge: it starts just beyond the orbit of Neptune and potentially extends out almost 1,000 AU.

When we started really searching the Kuiper Belt, what we found forced us to reevaluate how we view the solar system. The most drastic consequence was the demotion of Pluto from a full-fledged planet to a dwarf planet. Since one of the criteria for being a planet is that it has cleared its orbit of debris, the discovery of the Kuiper Belt disqualified Pluto from having that designation (via Library of Congress). But although Pluto may have been dislodged from its position as the least of the planets, it now stands as king of the dwarf planets and possibly the largest object in the Kuiper Belt. Coming in at a close second (it's hard to tell from over 60 AU) is Eris, followed by Makemake and Haumea (via Canadian Space Agency).

More to discover

What lies beyond the Kuiper Belt is largely mysterious. Astronomers hypothesize the existence of the Oort Cloud to account for the existence of long-period comets with eccentric orbits, but to date, we've never actually seen anything that would definitively prove its existence. Given that the Oort Cloud is speculated to begin at a whopping 2,000 AU from the sun, it's no wonder that we haven't seen anything. We have found clues, though. In 2004, a new class of object was found, floating in the icy gulf between the Kuiper Belt and the theorized Oort Cloud. Sedna (named for an Inuit goddess of the ocean) orbits the sun every 10,000 years. The closest it ever gets to the sun is still at least twice as far away as Pluto, and it can range as far as 936 AU, the very limit of what we consider the Kuiper Belt (via Universe Today).

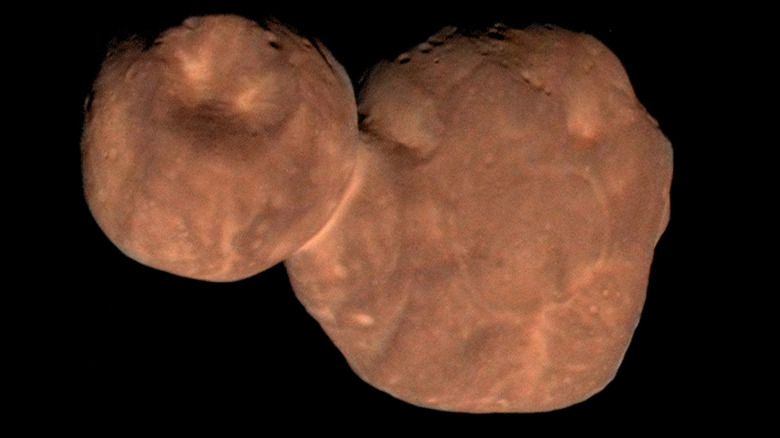

To date, only the New Horizons mission has been sent to explore what lies beyond Neptune. Launched in 2006, it spent nine years on its way to the Kuiper Belt, where it took unprecedented photos of Pluto and its moon Charon in 2015. Four years and a billion miles later, it flew by Arrokoth, an icy rock unknown to science until it was discovered en route to Pluto. Although NASA is prepared to extend the New Horizons mission, there are no future missions to the Kuiper Belt planned.