Artifacts Found While Building Subway Systems

If you dream of archaeological glory, you could either run out and buy yourself a fedora and a bullwhip, or you could just join the construction crew on a subway dig. In the first scenario, you get chased by Nazis and giant boulders, and in the second you get to accidentally stumble onto awesome archaeological finds without all the mortal peril. Now, if mortal peril is your thing, then get the fedora and the bullwhip. If not, it seems almost inevitable that your job on the metro line will give you the archaeological fame you're looking for. If you don't believe us, here's proof of just how easy it is. Apparently.

The remains of a Byzantine shipping fleet

The construction of a subsea rail tunnel connecting the Asian and European sides of Istanbul was halted so that archaeologists could recover some "clay pots" and "other stuff." At least, that's what Turkey's prime minister grumbled when his epic subway project was delayed for years because earthmovers kept finding artifacts under the Bosporus Strait.

According to NPR, the find includes the remains of 37 ships, the largest collection of shipwrecks found in a single location. Some of the ships are cargo vessels, while others are terrifying military galleys — the Byzantine navy was particularly known for its use of "Greek Fire," which could even set the surface of the sea aflame. Think wildfire from Game of Thrones only without Cersei Lannister smirking from the ramparts.

In total, more than 35,000 artifacts were found at the site, including coins, animal bones, and burial structures. The site is now believed to be the lost Port of Theodosius. It took the better part of a decade to pull all those artifacts from the tunnel, giving politicians plenty of time to grumble about how long it was taking. That was to be expected; Fundamentals in Grumbling is probably a required course at university for aspiring politicians. Nevertheless, archaeologists completed the excavation, the tunnel opened, and now everyone is living happily ever after, except for the students who have to document and protect each individual item. Hopefully they took Fundamentals in Grumbling as an elective.

Roman military barracks

If you're going to build a subway system, you probably shouldn't do it in Rome unless most of your contractors are also archaeologists. It's impossible to plant a potato in that part of the world without unearthing some pantheon or colosseum or something — if you're digging a whole subway system, it's kind of a given that you're going to end up finding something massive that brings your whole construction schedule to a halt.

According to the BBC, in 2016, crews uncovered a Roman military barracks over 9,700 square feet in size, which was thought to house the Emperor Hadrian's "Praetorian Guard." The find was significant enough that the city decided to create an "archaeological" metro station, which when you think about it kind of seems like a way-too-convenient solution to the whole "there's a Roman military barracks in the way of our subway tunnel" problem. Hey, let's not go around it or anything, let's just make it part of the metro station and everyone will think we're archaeological heroes, like Indiana Jones only without the heroism. Or the bullwhip. The site has 39 rooms, and the floors are patterned mosaics. That seems pretty fancy for a bunch of soldiers, but keep in mind that these were the emperor's personal bodyguards and "private military force," so mosaic floors were clearly an employment perk.

Ice age fossils

For many years Los Angeles went without the modern luxury of transportation that moves more than a few feet every 20 minutes or so. Then, someone finally got the bright idea to build a subway system. Duh.

The LA Metro Rail began operations back in the '90s and has slowly been expanding service over the years. According to SF Gate, paleontologists are always part of the construction efforts because the subway line cuts through parts of the infamous La Brea Tar Pits, where thousands of animals perished in the sticky asphalt that naturally formed in the area during the Pleistocene.

In 2014 the city decided to expand the metro's Purple Line, and not long after work on Phase Two began, crews uncovered an intact mammoth skull — one of only about 30 mammoths ever uncovered in the Los Angeles area. Since that monumental initial discovery, paleontologists have also unearthed the remains of other ice age-era animals such as mastodons, horses, and ancient camels, many of whom were probably trapped by that same sticky goo that interrupted the travels of those thousands of creatures that died at La Brea. When you think about it, transportation in the LA region really hasn't changed a whole lot since the Pleistocene. Back then it was gooey asphalt that slowed the flow of traffic; today it's a bunch of people rubbernecking fender-benders.

An ancient farm

According to NBC News, construction of the Metro C Line in Rome was running years behind schedule by 2014, and it wasn't because of bureaucrats or money. It was because construction crews kept finding stupid artifacts all over the place — or at least that's what you'd be likely hear from the people who just wanted to get the metro line moving, already.

For archaeologists, though, there's nothing stupid about all those artifacts, and it's worth a little schedule delay to remove and preserve items of archaeological significance. And Rome, as we've already established, is one of those places where you can't go anywhere without tripping over something of archaeological significance.

Starting in 2006, construction on the Metro C was repeatedly halted while archaeologists attempted to preserve the remains of a grand auditorium, and, more recently, the remains of a farm. The farm that crews discovered in 2014 wasn't just a little family operation but a major agricultural business, which included a 115-foot by 230-foot irrigation basin and a large drainage system. Archaeologists uncovered storage baskets, an iron pitchfork, peach pits that probably came from the farm's orchard, and evidence of a large waterwheel.

Incidentally, parts of the Metro C Line did get moving around the same time the farm was unearthed, and its maiden run was marred by delays that were totally unrelated to archaeology. It isn't just the preservation of ancient history that wrecks everyone's commute; it's also good old-fashioned incompetence.

An Aztec graveyard

Mexico City was once Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Aztec empire. So it's unsurprising that construction on the Mexico City subway line in 2010 uncovered some Aztec relics, including hundreds of figurines, some practical items like pots and plates, and 60 or so 500-year-old skeletons. According to History, the remains include 10 adults and 50 children who died around the time of the Spanish conquest in 1521.

The Aztecs have a reputation as a brutal warrior nation that practiced human sacrifice, but this discovery revealed the culture's softer side — the Aztecs sought to keep beloved family members close by burying them under their homes, and small children and infants were often placed into ceramic vessels because the vessels were thought to mimic the womb, providing comfort and security in the afterlife. Many of the bones recovered from the subway dig were buried in such a manner.

Mexico City has the second-largest metro system in North America, so city planners are used to having to revise their plans to accommodate archaeological discoveries. One of the lines had to be rerouted around an entire pyramid, and in 2009 archaeologists discovered a ritual skull rack during a subway expansion project. Skull racks were used to display the heads of enemy warriors who had been killed as sacrifices — now that's the Aztec culture we all know and find morbidly fascinating.

A Colonial era wall

Even New York City has artifacts, and they're not the remains of yellow cabs or characters from Sex in the City. Manhattan was first settled by the Dutch in 1624, and then the English came along in 1664 and told everyone that Manhattan was actually theirs, which was pretty much what the English spent most of their time doing in those days.

Anyway not much of those old settlements remain, because they were buried by centuries of pollution and Starbucks cups. That's why crews working on a subway tunnel were surprised to discover the remains of a 45-foot-long stone wall that archaeologists think dates back to at least the 1760s, possibly even the late 1600s. According to the New York Times, the wall is the remains of the original battery surrounding the old Colonial settlement and is likely the only such fortification that survived the Revolutionary War.

Besides the wall, workers also found 65,000 other historic artifacts, including coins, buttons, and pottery. And because it's New York, where people are not really known for their gentle approach to anything, the wall itself ended up in two pieces — smashed by a backhoe before anyone realized exactly what was being smashed.

Today a portion of the wall is on display at the South Ferry subway station, in one of those march-of-progress compromises. In a big city like New York, that's sadly the best option for preserving large pieces of archaeological history.

A sixth-century copper factory

Crews working on the notorious Metro C Line (where the discovery of the Roman Praetorian barracks and a commercial farm would later delay progress of the new subway extension) had already uncovered a historical treasure in 2008. Over the collective groans of every Roman commuter sitting in corresponding traffic jams, archaeologists were called in to excavate the remains of a sixth-century copper factory. According to History, crews uncovered ovens that were used to melt copper for making coins, architectural components, and copper pipes for Rome's very much ahead-of-its-time public plumbing system.

Like all subway-related architectural discoveries, this one messed up plans and inconvenienced people. Rome is pretty used to it, though. Italy has stringent conservation laws that dictate the handling of all archaeological finds, which are either removed, destroyed, or integrated into whatever project was responsible for uncovering them. Happily, it's mostly just entrances and stairwells that typically create problems, since the line itself runs deeper than the archaeological record.

Still, Roman artifacts are so numerous that it's almost like the real news is when crews don't uncover something significant. A sixth-century copper factory, a military barracks, and an ancient farm are practically yawn-worthy, especially compared to the astonishing discovery of nothing at all.

The elaborate grave of someone's pet dog

Traffic sucks, whether you're in Rome or Los Angeles, and it plagues just about every major city in the world. Take Athens, for example, where Smithsonian reports that the number of cars has ballooned over 2,000 percent in the past 30 years. So like every big metro area with a super-sucky traffic problem, the city decided to build a subway system. You've probably guessed the complication: Greece has a bunch of archaeological treasures buried just below the surface, which the new metro system necessarily had to disturb.

The Athens subway project didn't uncover any military barracks or copper factories, but a wealth of smaller objects like oil lamps, vases, and gold "danakes" — special coins minted so the dead could pay fare to enter the underworld, sort of like buying a ticket to a Halloween house that you never get to leave. But really the coolest discovery of the lot was not the (pretty cool!) fifth-century bronze head but an elaborate grave with a tile floor and terracotta walls where someone buried their pet dog. Besides enjoying a tomb far more luxurious than most humans who lived during that time, the dog was also buried with a copper-studded collar and two perfume bottles. Why a dog needs perfume bottles in the afterlife is unclear, unless it was a particularly stinky dog — but hey, as long as it was a well-loved stinky dog, right?

A complex of medieval churches

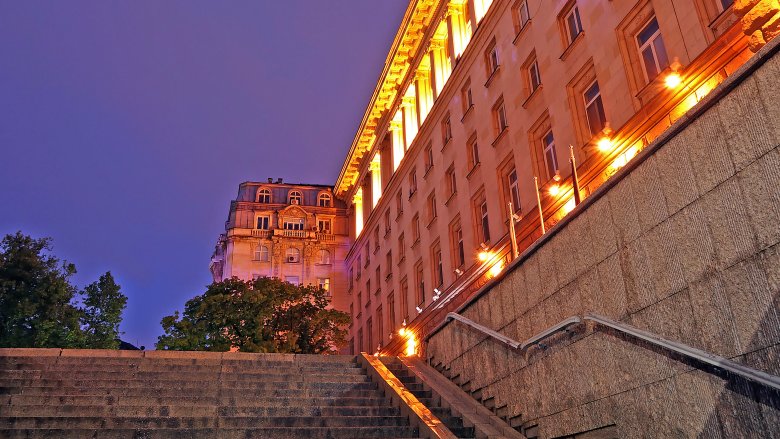

The familiar story of progress vs. antiquity was also repeated in the Bulgarian capital of Sofia, where crews working on a second metro line uncovered the remains of a medieval church, right next to a popular retail center. According to one local news agency, the church is thought to date from the fifth or sixth century, and there were even intact 12th-century murals inside.

Construction on the metro was halted to give archaeologists time to recover the artifacts, and lo, two more medieval churches emerged from the ground. The newer discoveries date from the 14th and 16th centuries — the latter has six layers of murals and was probably used until the late 1800s, when much less archaeologically inclined city planners decided that history had to make way for progress.

This time progress makes way for history. The complex happens to be in the heart of Sofia, where there is already an impressive collection of well-preserved archaeological sites dating from antiquity to the Middle Ages. And great news for travelers: Sofia has been hailed as "the most affordable capital city in Europe," so if archaeological wonders uncovered during subway digs is your thing, we've heard that there's also a great shopping center right next door.

Ancient sewers

There's nothing like a stroll through some ancient sewers to top off your visit to Athens, and if you visit the Monastiraki subway station you can do exactly that. According to Reuters, in ancient times, the Eridanos river flowed through the city of Athens, and because ancient people were gross the river was mostly just used as a sewer. In those days the waterway was covered with a brick roof and lined by a complex of buildings, including homes, workshops, and warehouses.

Archaeologists first uncovered the poop-stained archaeological wonder while building a subway station near the Plaka district, close to the Acropolis. In what was a shockingly prescient long-term decision, the city decided to turn the ancient underground river into a tourist attraction — it now flows right through the subway station. Humans are still fascinated by the idea today: A glass pedestrian bridge lets tourists walk around the complex and admire the architecture. Of the sewage system. Fortunately, the ancient poop has long since washed away so the water isn't quite as smelly as it was in antiquity because that would make for an exceedingly unpleasant commute.

A plague pit

In the 14th century, 75 million people died from plague. All 75 million deaths can be traced back to 12 Genoese trading ships that arrived in Sicily in 1347 with a cargo full of dead guys and a few sailors who were still mobile enough to deliver the disease to the unsuspecting people hanging around the docks.

According to the BBC, Britain was particularly hard hit — some estimates say the Black Death wiped out 60 percent of the population. So it seems a lot more likely that a subway dig would encounter the bones of plague victims than that it would encounter random other stuff, like dog graves and ancient sewers. In 2014 the London Crossrail project found a mass grave, and the DNA from Yersinia pestis — the bacterium that caused the Black Death — was found in the teeth of the skeletons buried there.

Historians have always known that the Black Death's victims were dumped in a mass grave somewhere outside London, but until the Crossrail dig it was unclear where that grave was. Now underground scans have revealed even more graves in the area, so that should keep archaeologists happily occupied for a few years. And by the way, just in case you thought you were safe — plague still kills around 2,000 people every year. You're probably not going to encounter it when riding the Crossrail through those ancient plague pits, but you should probably avoid close contact with chipmunks.