Civil War Timeline Explained

The American Civil War was one of the most momentous and complex events in United States history. It lasted from 1861 to 1865 and resulted in the deaths of an estimated 620,000 to 850,000 Americans (via History). It was the most divisive period of American history, a time when brother fought brother and father fought son, and countless families were irreparably damaged and split apart, creating wounds that for many have never healed.

The main cause of the Civil War was slavery, which Southern states were fighting to preserve. As the American Battlefield Trust shows, a series of events from the American Revolution to the election of Abraham Lincoln set the stage for the war. Though slavery was legalized under the Constitution, the Northern states had slowly started to phase it out, while in the South, it had become even more entrenched. The Missouri Compromise in 1820 prohibited slavery north of the Mason-Dixon line, and the Compromise of 1850 saw California added as a free state with slavery outlawed.

Tensions were simmering between pro and anti-slavery groups, and one of the biggest battlefields became the Kansas territory, where guerilla warfare started to break out. With the 1857 Supreme Court ruling that slaves were not citizens but property, and John Brown's 1859 deadly raid at Harper's Ferry in Virginia, things were reaching a boiling point in America, and the next stop was war.

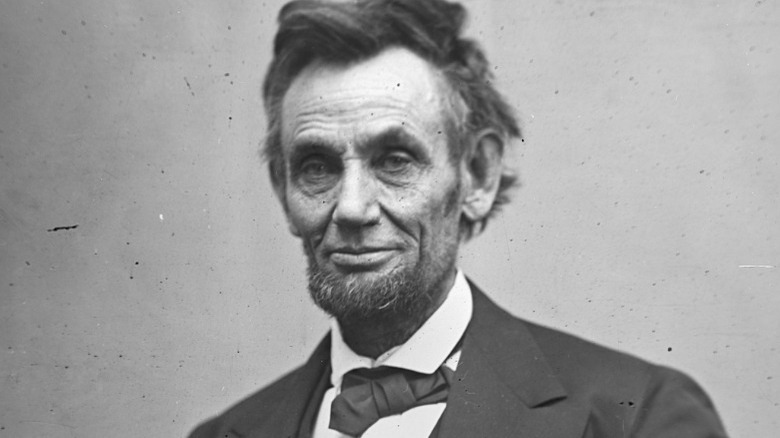

The 1860 election of Abraham Lincoln

One of the surest signs of potential trouble before the Civil War was the 1860 election of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency. As the National Parks Service explains, Lincoln was the Republican Party's candidate that year, and they were endorsing an anti-slavery plank. Their opposition to slavery was on a moral basis, and they were against the introduction of slavery in new states and territories.

The Republicans' competitors were the Democratic and Constitutional Union parties. The Democrats were hopelessly split over the issue of slavery and actually elected two different candidates, one representing the North and one representing the South. The Southern states were so opposed to Lincoln's candidacy over his views on slavery that his name did not even appear on their ballots. Still, Lincoln managed to win 40% of the popular vote and 180 votes in the Electoral College, sealing his victory (via the Miller Center).

The Southern states' reaction to Lincoln's election was as unfavorable as you would expect. According to James McPherson in "Battle Cry of Freedom," South Carolina called a secession convention and promptly voted 169-0 to secede from the United States. By the beginning of February 1861, six other states had joined South Carolina: Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas — and the Union was officially cut apart.

The first salvo starts at Fort Sumter

When South Carolina seceded in December 1860, it brought up a very tricky issue for Maj. Robert Anderson and his companies of Union troops. Anderson and the troops were located in Charleston overseeing the construction of the Fort Sumter Army base (via History). With South Carolina no longer recognizing the authority of the Union, however, it quickly brought into question how Anderson and his troops should act to maintain their hold of the last remaining federal territory in the state.

When the new year turned over, Abraham Lincoln tried to reinforce the fort's dwindling supplies, but his ships turned around when South Carolina militias started reigning artillery fire down on them from the coast. Lincoln was sworn in that March, and by then thousands of Southern troops were swarming Sumter. Meanwhile, per the American Battlefield Trust, the Confederate States of America was officially created the month prior in Montgomery, Alabama, with Jefferson Davis being named its inaugural president.

Davis ordered Confederate Brig. Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard to take the fort by force in early March, and when Lincoln moved to resupply Sumter in mid-April, Beauregard took his chance. The Confederates fired on Sumter early on the morning of April 12, starting a 34-hour engagement that ended with Maj. Anderson evacuating the fort for the Confederates to take over. Following the battle, Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina, and Tennessee all seceded, completing the Confederacy (via "Battle Cry of Freedom").

The first Battle of Bull Run at Manassas

After the Battle of Fort Sumter, the reaction in the North was a frenzy of excitement and a swell of nationalism. According to James McPherson in "Battle Cry of Freedom," President Abraham Lincoln immediately called for 75,000 volunteers for 90 days of militia service, and there was an outpouring of support. Even Democrats who had previously gone against Lincoln were now supporting his fight against the secessionist states.

However as the American Battlefield Trust shows, the enthusiasm and quick recruitment of troops proved to be a double-edged sword. Northerners expected quick results, and the 90-day limit on the volunteers gave Lincoln a very real ticking clock he had to observe. Thinking the war would be over in short order, 35,000 undertrained and green Union troops marched to meet the Confederate Army at Bull Run Creek in Manassas, Virginia, not far from Washington D.C.

Amazingly, Northern civilians and congressmen came out to watch the spectacle part-way through, but they soon regretted their decision. On July 21, 1861, the Union Army attacked the Confederates but was repelled in what quickly turned into a rout. Union soldiers mixed with Northern civilians and congressmen fleeing from the battlefield and Southern guns. It was the first real fight of the Civil War and the Union got smashed, returning to Washington to regroup.

Ulysses Grant takes Tennessee and enters the Hornet's Nest

After the first real Civil War battle at Bull Run in Manassas, small battles continued through the end of the year. The Union tried and failed to take Missouri — twice — and were also smashed at the Battle of Ball's Bluff when they tried to cross the Potomac River into Virginia (via the National Parks Service). However, Union fortunes began to change in Tennessee, starting in February 1862.

According to James McPherson in "Ordeal by Fire," in February, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and his Union Army captured Fts. Henry and Donelson in northern Tennessee, taking 13,000 Confederate prisoners. The battles also gave the Union control of the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers, which led to Corinth, Mississippi, and Nashville — two important Confederate strongholds. The Union took Nashville on February 23, 1862, and a contingent soon moved south on the Tennessee River to the now famous Shiloh Church at Pittsburgh's Landing on the way to Corinth.

At Pittsburgh's Landing, a surprise Confederate attack on April 6 slowly pushed the Union forces back, squeezing them between the Tennessee River and Shiloh Church (via the American Battlefield Trust). Still, the Union held through the next day, eventually forcing a Confederate retreat to Corinth. The climax of the battle occurred in an area named the "Hornet's Nest," where countless Confederate lives were lost in some of the war's most vicious fighting.

The Union captures New Orleans

Fresh off the heels of Ulysses S. Grant's victories in Tennessee, the Union got even better news from the Gulf of Mexico. As per History, it was just over two weeks after the Battle of Shiloh that Adm. David Farragut captured the crown city of New Orleans on the Mississippi River.

According to the Navy, Farragut started his charge of New Orleans from the mouth of the Mississippi on April 24, 1862, forcing his way past multiple forts on his way north. The rebel naval force was formidable, and they had sent flaming boats to obstruct Farragut's path. Still, Farragut blasted through the Confederate defenses, downing several ships while only losing one himself.

On April 25, the Union streamed into New Orleans, immediately taking over the city and opening up the path to Vicksburg, Mississippi. Union forces took control of the northern section of the Mississippi River following the Battle of Memphis a month later, leaving Vicksburg as all that stood between the Union and complete control of the river (via the National Parks Service). Union control of the Mississippi River would have effectively split the Confederacy in half, severely weakening them.

Stonewall Jackson's masterful Shenandoah Valley Campaign

While the Union was having success against the Confederates in Tennessee and New Orleans, it was a different story in the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia. According to the Shenandoah Valley National Historical District, the Union was trying to capture the Confederate capital in Richmond, Virginia, by attacking it from both the southeast and north. The Union Army had 130,000 troops combined, but the Confederates had an ace up their sleeve: Gen. Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson.

As James McPherson explains in "Ordeal by Fire," Jackson came up with a genius battle plan to keep the federals from squeezing the capital at Richmond. His goal was to make the federal forces chase him instead of fighting in Richmond with the other troops. Jackson traveled in a "zigzag movement" throughout the Shenandoah Valley, crisscrossing the Blue Ridge Mountains and engaging Union troops in several battles. His careful use of intelligence allowed him to keep the Union from trapping him, and his troops marched everywhere in the valley to keep them confused.

Eventually, Jackson was able to link up with Gen. Robert E. Lee in Virginia, after thoroughly discombobulating the Union. Incredibly, in the span of just a month from May to June 1862, Jackson managed to confound and practically immobilize 60,000 Union troops with his force of barely 17,000, inflicting serious casualties and tanking Union morale.

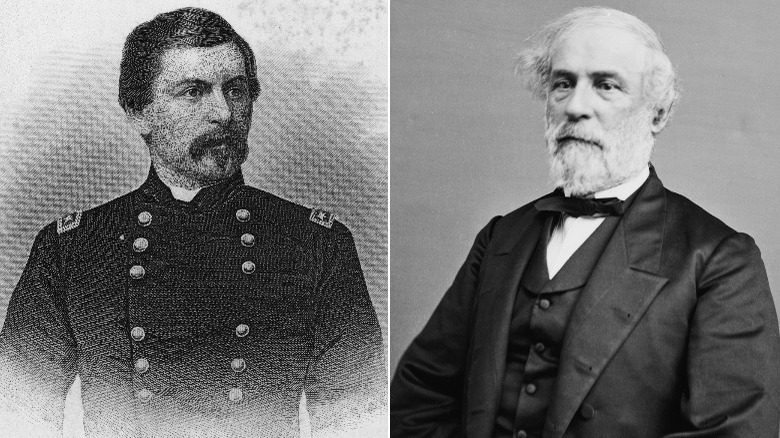

Granny Lee takes over as McClellan flails

To lead the takeover of the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, President Abraham Lincoln turned to his general-in-chief of all Union armies: George B. McClellan. According to History, Lincoln had installed McClellan as his top general in November 1861, and by the end of January 1862, he was pressing for him to lead an invasion. However, McClellan's timidity kept getting in the way, and he consistently asked Lincoln for more troops due to his overestimation of the Confederate strength.

McClellan refused to attack the rebels who were still stationed in Manassas after the first Bull Run, instead persuading Lincoln to allow him to start his push toward Richmond from the southeast coast and move inland. Lincoln agreed, though he demoted McClellan, and by the end of May, over 100,000 troops were on Richmond's doorstep (via the American Battlefield Trust). Yet, at the Battle of Seven Pines, the Confederates stopped the Union from taking their capital, while "Stonewall" Jackson's Shenandoah Valley campaign continued to tie up Northern reinforcements.

The Confederate commander died at Seven Pines, and put in his place was Gen. Robert E. Lee. Initially, troops were skeptical of Lee, and had even nicknamed him "Granny Lee" over his missteps the year prior (via HistoryNet). Yet, Lee led an offensive known as the Seven Days Battles in June, which secured his reputation by pushing back the Union and saving Richmond.

Antietam and the Emancipation Proclamation

Following the Union losses during George B. McClellan's failed Peninsula Campaign, President Abraham Lincoln needed a federal victory, and bad. As History shows, while McClellan was flailing against Robert E. Lee, Lincoln was crafting the Emancipation Proclamation in Washington D.C. Lincoln wanted to announce the proclamation, which declared that all slaves still shackled in the Confederacy were now considered free, but he wanted to do it following a Union battle victory.

Meanwhile, planning to capitalize on McClellan's retreat, Lee organized the Confederate invasion of the North. His plan was to invade through Maryland, but everything almost turned into a disaster when McClellan, by chance, came upon a copy of Lee's battle plans. In the right hands, this information could have been devastating, but as James McPherson explains in "Battle Cry of Freedom," McClellan's ineptness got the best of him. His inexplicable delay in confronting Lee allowed the Confederates to reorganize, and the two armies finally met on September 17, 1862, in Sharpsburg, Maryland, at the Battle of Antietam.

The Union won the battle, which ended up being the single bloodiest day of the war, with 23,000 casualties and over 3,600 dead (via the National Parks Service). Still, Lee's invasion of the North was stopped — though McClellan again inexplicably failed to follow up — Lincoln eventually announced the Emancipation Proclamation days later on September 22.

Burnside leads the Union to disaster at Fredericksburg

After the Battle of Antietam, though a Union victory, President Abraham Lincoln was through with Gen. George B. McClellan. As the American Battlefield Trust explains, McClellan's refusal to keep on the attack after the battle and hunt down the retreating Confederates was the final straw. Lincoln relieved McClellan and instead put Ambrose E. Burnside in his place. Burnside acted quickly to establish his control over the Union's forces, and started with an attack on the town of Fredericksburg, Virginia.

Though his forces were in place by mid-November 1862, Burnside didn't authorize an attack until December 11 due to supply issues. That morning, Burnside ordered the Union artillery to shell Fredericksburg into submission. Then, 123,000 Union troops crossed the river and met 78,000 Confederate soliders at Marye's Heights and Prospect Hill, but they failed to move them from their strongholds. After 18,500 casualties — 12,500 from the Union alone — Burnside withdrew back over the Rappahannock.

At the same time, to the east in Tennessee, Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans was engaging the rebels under Gen. Braxton Bragg in Murfreesboro. On January 3, 1863, Rosecrans was able to force Bragg to retreat, capturing central Tennessee at the Battle of Stones River. This gave the Union a huge victory to help promote the Emancipation Proclamation, which had went into effect on January 1.

Lee's greatest victory and Stonewall Jackson's death

With Gen. Burnside's failure at Fredericksburg, President Abraham Lincoln had no choice but to replace him with Gen. Joseph Hooker. Hooker wanted to smash Robert E. Lee and the Confederate Army, who were still holed up in Fredericksburg, and the Union Army crossed the Rappahannock River again on April 29, 1863, to start an attack (per the American Battlefield Trust). Knowing that Lee was short on troops, Gen. Hooker's plan was to split the cavalry and infantry apart, with each of them encircling Lee on his left and right flank.

Lee, sensing his vulnerability to attack, made the incredible decision to split his own army into two in an effort to flank and trap the advancing Union troops. At the Battle of Chancellorsville, 100,000 Union forces engaged just under 60,000 Confederate soldiers and were thoroughly routed due to a brilliant attack by "Stonewall" Jackson on the Union flank. Jackson had taken his half of the Confederate troops and circled the entire Union Army without them realizing, and his forces crashed through the Union's exposed right flank and inflicted devastating casualties.

The battle was a stunning success for Lee and the Confederates and was only marred by the death of Jackson, who was mistakenly shot by his own troops. The Union retreated back across the river on May 6, ending their pursuit of Lee.

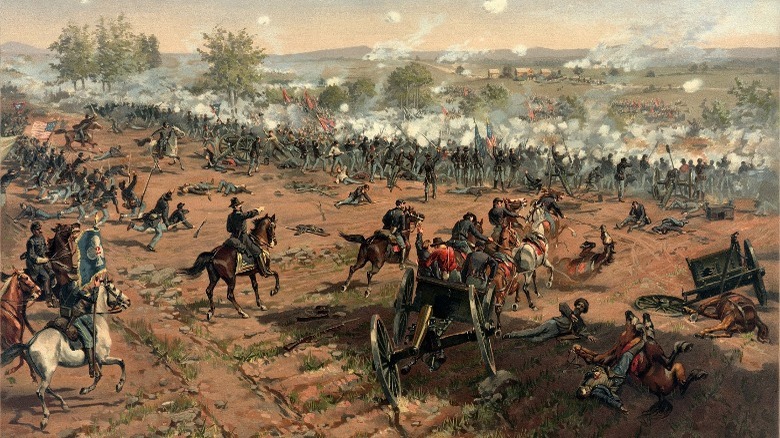

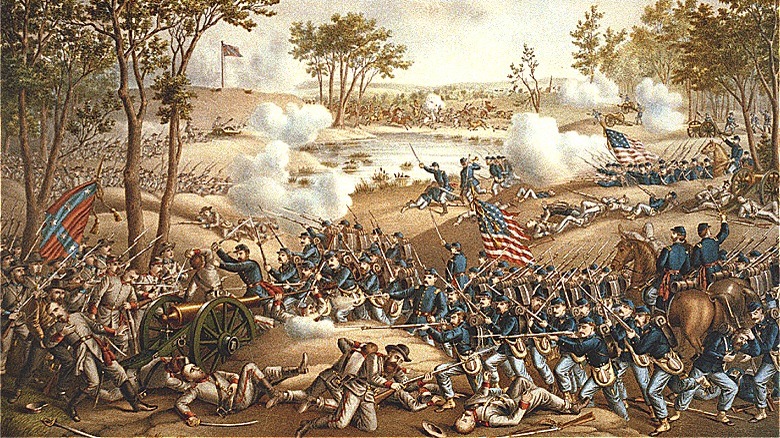

The bloodiest battle of the war, Gettysburg

Wanting to capitalize on the victory at Chancellorsville, Gen. Robert E. Lee decided to take the fight back to the North and attempt another invasion to rectify his failure in the previous fall at Antietam (per HistoryNet). Rebel troops moved forward in May 1863, and the Confederate cavalry also rode north to disrupt the Union Army's supply lines.

According to James McPherson in "Ordeal by Fire," the Confederate troops ravaged the countryside of Pennsylvania for supplies, and even kidnapped unsuspecting African Americans and sent them to the South to be enslaved. On their way to requisition a large storage of shoes, the Confederates ran head first into the Union Army at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on July 1, 1863.

Initially, the Confederates had some success against the Union in the west, but Lee, deprived of his cavalry, who were still disrupting supply lines, delayed in launching an attack which his general never carried out. In the interim, more federal troops arrived in Gettysburg, shifting the tide to the Union. Repeated attacks thrust forward by the Confederates failed to dislodge the Union, including the disastrous Pickett's Charge, and by the end of the battle, the troops had combined for nearly 50,000 casualties over three days. On July 4, 1863, Lee's army started their dejected march back to Virginia, exhausted and demoralized.

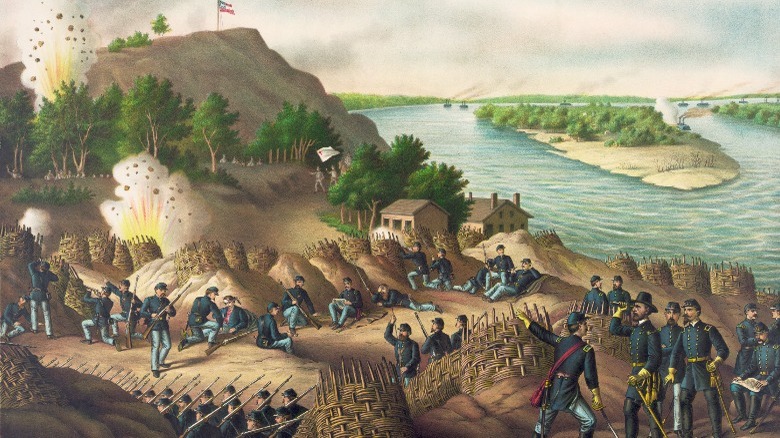

The siege and fall of Vicksburg

While the Confederate and Union armies were slugging it out at Gettysburg, out east, Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant was laying siege to Vicksburg on the Mississippi River. Vicksburg was the last Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River and all that stood in the way of total Union control. Grant had tried to take Vicksburg the previous summer at the First Battle of Vicksburg, but failed when his navy was turned back (via HistoryNet).

Another disastrous attempt over the winter resulted in 1,800 Union casualties, so Grant tried for a third time beginning in May 1863. Grant and his troops were on the west side of the Mississippi River to the north of Vicksburg, but they needed to get over to the east side to attack the fort itself. Throughout the early spring, Grant's troops marched to the south of Vicksburg, where they eventually met up with Adm. Dixon Porter, who had narrowly made it past the forts while floating down the river (via the American Battlefield Trust).

After they met downstream, Grant and Porter transferred all of Grant's troops to the east side of the river, where they were ready to start marching on Vicksburg. After failing to capture the fort, Grant's garrison settled in and bombarded the fort with artillery fire for 47 days. Finally, on July 4, 1863, the day after the Union victory at Gettysburg, the Confederates finally surrendered Vicksburg to Grant.

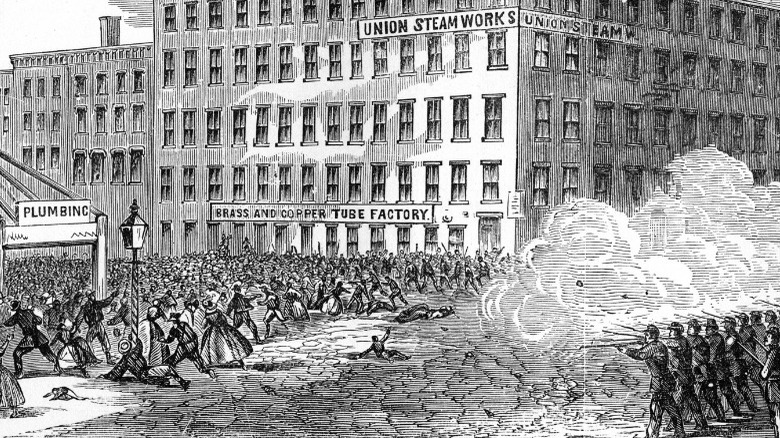

The New York City draft riots

Though Abraham Lincoln had been elected to the [residency due to his support in the North, there was hardly uniform agreement with the war in what remained of the Union. As History explains, one of the hot spots from the beginning was New York City. Many politicians from New York promoted rapprochement with the Confederacy, and hostilities really increased in the city following Lincoln's announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation in September 1862.

Yet, what really stirred up trouble was the announcement of a new draft law in March 1863. An unequal system where the wealthy could pay their way out of fighting fueled mounting anger among the working class and poor, and soon violence erupted. As Leslie M. Harris explains in "In the Shadow of Slavery," the March announcement stipulated that a draft lottery would be held, and on July 11, 1863, just a week after the Gettysburg victory, the first lottery commenced. Less than 48 hours later, the town was awash with violence and flames.

Rioters targeted military buildings and government structures first, but they quickly turned their attention to African Americans and toward "things symbolic of Black political, economic, and social power." The riots lasted five days and 11 African Americans were lynched by angry white mobs who blamed them for the war. Eventually, federal troops came in to end the disturbance, but there was much damage already done, especially to Black Americans.

The 54th Massachusetts gets their chance

While angry white mobs were attacking African Americans in New York City over the new draft laws, the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment was fighting on the front lines of the war. Per the National Museum of the U.S. Army, the 54th Massachusetts was a regiment staffed with only African American soldiers and white officers. Initially raised in March 1863, on July 16, as the New York draft riots were raging, the 54th first went into battle. Heavily outnumbered, they resisted a Confederate onslaught before bringing the fight to Dixie itself in Charleston, South Carolina.

On July 18, 1863, the 54th engaged in a full-frontal assault on the Fort Wagner battery, braving bullets and artillery fire to plant the Union flag in the Confederate fort. Though the Union was driven back during the horrific battle, the 54th Massachusetts distinguished themselves with their gallantry and incredible bravery.

Hundreds of miles west, Union Gen. William Rosecrans was still fighting against Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg following the Battle at Stones River in January 1863. In September 1863, the two armies met at the Battle of Chickamauga in Georgia, which resulted in a Confederate triumph (via History). However, the victory would be short-lived, as the Union, reinforced by Gen. Ulysses Grant, would defeat the Confederates at the Battle of Chattanooga in November, securing Tennessee for the Union.

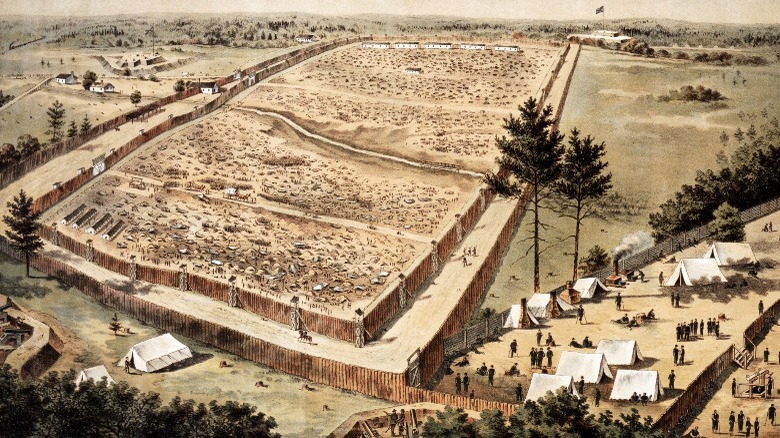

Andersonville Prison goes up and Sherman takes Meridian

Some of the worst horrors of the war took place not on the battlefield, but at the infamous Andersonville Prison Camp in Georgia. According to James McPherson in "Battle Cry of Freedom," the camp was originally built in early 1864 to accommodate the massive influx of Union prisoners. However, it was incredibly undersized, and "disease, exposure, or malnutrition" ran rampant. Unable to supply their own soldiers, Confederates could not find enough food to adequately feed their prisoners, and 13,000 died in captivity. At times as many as 100 died per day, and matters were only made worse by the suspension of prisoner exchanges.

The prisoner exchange system had been suspended in July 1863 after President Abraham Lincoln had issued General Order 252 (via the National Parks Service). The order was in response to the Confederacy's passage of legislation that declared Black prisoners would not be recognized as soldiers but would be subject to either execution or enslavement upon capture. The lack of exchange caused Andersonville to swell to over 30,000 prisoners, more than three times its intended capacity.

While Andersonville was being constructed in Georgia, to the east in Mississippi, Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman was busy following up on Grant's victory at Vicksburg (per Mississippi History Now). In February 1864, Sherman's troops marched 150 miles east from the fort to Meridian, Mississippi. They captured the city, setting the stage for Sherman's capture of Georgia at the end of the year.

The Overland Campaign and the Union's slaughter at Cold Harbor

After the Battle of Gettysburg, President Abraham Lincoln once again shifted the top brass for the Union Army, and named Gen. Ulysses S. Grant as new head commander (via History). Immediately, Grant started working on a plan to confront Gen. Robert E. Lee and his Confederate troops in Virginia. Using three different armies all working together, Grant planned to slowly smash the rebels into submission.

The first engagement of what became known as the Overland Campaign was the Battle of the Wilderness near Fredericksburg on May 5, 1864. The incredibly dense vegetation of the woods obscured views of the enemy, and fighting was horrific. Many soldiers fell victim to a raging inferno that was ignited by gunfire. Fighting to a stalemate, Grant continued the Union pursuit of Lee by trying to get around his right flank to the southeast. However, Lee anticipated Grant's move, and the two armies met again at the Battle of the Spotsylvania Court House.

Fighting it out for weeks, neither side was able to conclusively defeat the other, and on May 21, Grant took his men southeast again. They continued to meet rebel resistance, and in early June, the Union was thoroughly defeated at the Battle of Cold Harbor — at one point losing 7,000 men in under an hour. Following Cold Harbor, Grant again chased the Confederates back to Petersburg, where they started a siege of the town in June.

Gen. Tecumseh Sherman takes Atlanta and Lincoln get reelected

While Gen. Ulysses S. Grant was laying siege to Gen. Robert E. Lee's troops in Petersburg, Virginia, Gen. Tecumseh Sherman was following up on his victory at Meridian in February. By early May of 1864, Sherman had 100,000 troops near Chattanooga, Tennessee, and was preparing for an assault on Atlanta, Georgia (per "Ordeal by Fire"). Sherman's troops met the rebels at the Battle of Resaca on May 13, and the Confederates were soon sent back on the retreat.

Sherman continued to pursue the rebels back to Atlanta, and by mid-July, the Union was on the capital's doorstep (via the American Battlefield Trust). Following a brief Confederate attack, known as the Battle of Peach Tree Creek, on July 20, the two armies met for the Battle of Atlanta starting the next day. The battle was again inconclusive, and Sherman ended up laying siege to the city until September 1, 1864, when the Confederates finally abandoned Atlanta to the Union.

Meanwhile, back in the north, Abraham Lincoln was set to face his former general, George McClellan, in the 1864 presidential election. Lincoln defeated McClellan in the Electoral College by a margin of 212-21, and Republicans also won big in the congressional elections. If it was a referendum on the war and emancipation, the American people clearly sided with Lincoln.

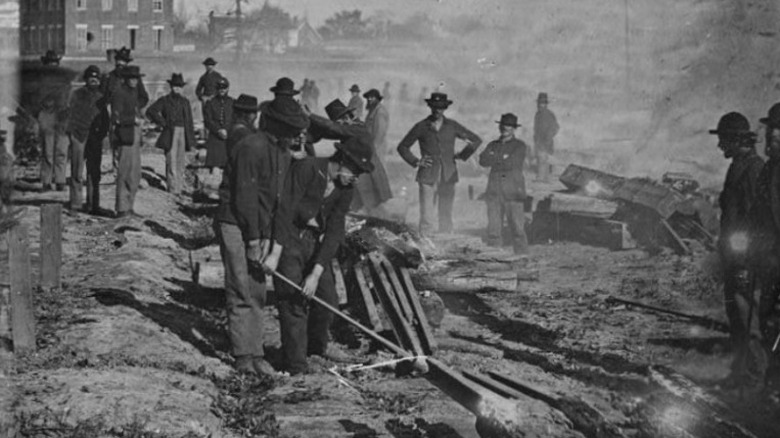

Sherman's March to the Sea

When Atlanta fell to Union forces on September 2, 1864, it was an ominous sign for the Confederacy. An important industrial center and railroad hub, the loss of Atlanta was a huge blow for the South (via History). Gen. Tecumseh Sherman was determined to continue the Union push into rebel territory by executing his now famous "March to the Sea." Sherman's March to the Sea was a nearly 300-mile trip from Atlanta to the coast at Savannah that lasted from mid-November to mid-December 1864. Union troops left Atlanta drowning in flames, and nearly a third of the city was destroyed before the fire was put out, according to National Geographic.

Sherman's plan was to smash through Confederate defenses and teach the secessionist Georgians a lesson in hospitality. Anyone who stood in their path, soldier or civilian, was quickly pushed aside. Sherman's troops raided farms for food, took livestock, destroyed railroads (pictured above), and burned the property of those who tried to resist. They arrived in Savannah on December 21 and took over the city.

Meanwhile, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's Petersburg Campaign finally produced results after nine months of siege. At the beginning of April 1865, the Union pushed through the last of the Confederate trenches, capturing the Confederate capital at Richmond and portending the end of the war.

The Army of Northern Virginia surrenders at Appomattox

After the fall of Petersburg and Richmond on April 2, 1865, the Confederacy was desperate. In fact, the month prior, the legislature had, incredibly, passed a bill actually proposing to enlist slaves into the Confederate Army (via "Ordeal by Fire"). Of course, actually freeing them was out of the question, but the Confederate government wanted (and needed) them to fight for their own enslavement. Ironically, on the other side of the rapidly expanding Union border, African American troops from the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry marched into the former Confederate capital on April 3 to claim it in the name of freedom for the North.

At the same time, the Confederates under Gen. Robert E. Lee were quickly trying to outrun a Union force more than twice their size. On April 6, the Battle of Sayler's Creek led to the capture of 7,000 Confederates, and by April 9, Lee knew the war was over. His beleaguered forces were starving to death after Union forces captured their last rations, and he reluctantly signed the surrender of the Confederacy at the house of Wilmer McLean in Appomattox, Virginia. The Civil War was finally over.

Five days following Lee's surrender, on April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Booth murdered President Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theater. Union troops in turn killed Booth on April 26, and the bloodshed was finally over.