World War II European Front Timeline Explained

Hindsight is 20/20, the saying goes, and it's easy to look back at the European history of the early 20th century and wonder why things — particularly, things in Germany — went so very wrong so very quickly. What happened, says The Weiner Holocaust Library, was complicated. At the time Adolph Hitler was made chancellor, his Nazi party was one of three political parties. That was in 1933, and after some serious election campaigning — bolstered by claims of a mysteriously brewing coup to overthrow Germany's Weimar Republic — and the burning of the Reichstag, a state of emergency was declared. Not only did it put a greater-than-normal amount of power into the hands of the Nazis, but it also stymied basic rights like the freedom of speech alongside a widespread effort to make it quite clear that if people knew what was good for them, they'd be voting Nazi.

And they did — which was especially important when it came to the Enabling Law. Proposed on March 23, 1933, it pretty much gave Hitler the authority he needed to pass any laws he wanted. Only one political party opposed it — with many vocal opponents finding themselves in the newly-opened Dachau concentration camp — and when it passed, it was by a whopping 444 to 94 votes.

What followed was the assassination and arrests of other Hitler naysayers, the Night of the Long Knives, and the death of the German president. And then? World War II. Let's look at how it played out.

Aug. 18, 1939: The start of the child euthanasia program

The Third Reich was known for their relentless crusade against those they deemed unworthy of being a part of their idealized Aryan race, and it's worth backtracking to just a few weeks prior to the official declarations of war to when this crusade began. Officially, it was on Aug. 18, 1939, when the Reich Ministry of the Interior made a widespread practice into actual law. For a few months prior, Nazi physicians had been working out the logistics of implementing a euthanasia program targeting people they declared "life unworthy of life," which the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum described as "individuals who — they believed — because of severe psychiatric, neurological, or physical disabilities represented both a genetic and a financial burden on German society and the state."

Doctors and nurses were given orders to report any children under 3 years old who were believed to have a mental or physical disability, and starting in October, parents would be ordered to take their children to special health wards. There, they would be euthanized.

The International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance says that it wasn't until 1998 that historians identified one of the first victims. Known only as "Child K," his parents petitioned Hitler himself for permission to carry out a so-called "mercy killing." The baby was euthanized on July 1, 1939. Although History says that the program was officially halted on Aug. 18, 1941 — in response to public outrage — it continued outside of Germany. Estimates suggest that at least 100,000 children were killed via the program.

Sept. 1-3, 1939: Hitler invades Poland, the Allies declare war

When Adolf Hitler was firmly cemented at the top of Germany and the Third Reich, one of the first things he did was equal parts unlikely and conniving: He signed a non-aggression pact with Poland, not because he intended to honor it, but because he didn't want Poland and France taking the first shots at Germany before he was ready.

Then, on Sept. 1, 1939, he was ready. After going back on the deal Germany made post-WWI, he had already rebuilt the nation's military and annexed Austria — and then, he invaded Poland while claiming the country had been unfairly persecuting Germans living there. This came on the heels of another non-aggression pact — this time signed with the Soviet Union — which left the 1.5 million troops free to steamroll their way through a Poland that was standing on its own. Their relatively small army was quickly decimated, but backup was coming.

Until the invasion, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum says Britain and France had been operating under a policy of appeasement: In other words, Hitler could have what he wanted as long as it wasn't too much. Poland was too much, and honoring their promise to protect Poland should the need arise, they declared war on Germany on Sept. 3. Still, Warsaw surrendered on the 28th, and German occupation and annexation began in earnest in October.

May 26 - June 4, 1940: Operation Dynamo/Dunkirk

In the months following the invasion of Poland, Allied forces continued to take on German troops in a fight along the borders of Belgium and France. Then, in May of 1940, German forces split and started working their way in two directions. On the heels of Hitler's May 12 order to invade France, one group headed for northern France via Holland and Belgium, while the other cut through Luxembourg before they, too, headed for northern France. Allied forces had their backs up against a literal wall, and by May 25, they had been forced back against the water with only one port city remaining to them: Dunkirk.

What followed was one of the most decisive moments of the war, which — had things been done differently — could have ended on the beaches of Dunkirk. Instead, Historic U.K. says Hitler made a decision that was sort of baffling: He stopped advancing. Instead of crushing the 330,000+ Allied troops that were trapped, his 3-day halt gave the Allies the chance to brave heavy fire from the surrounding military to dispatch hundreds of ships — including small pleasure boats sourced from U.K. civilians — and rescue more than 338,000 British, French, and Canadian soldiers.

Hitler deemed the whole thing a massive success, says English Heritage, but the Allies and Winston Churchill spun it a different way: It was a miracle, and the Allies would go on to fight another day.

June 14, 1940: The first political prisoners are sent to Auschwitz/Paris falls

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum says that fight only moved from the eastern front to the western with Adolf Hitler's May 1940 invasion of France. Things moved very, very quickly: The Netherlands and Belgium surrendered in May, and on June 14, Paris fell to German occupation. The day, says History, saw Paris residents wake up to a warning of an 8 pm curfew and an announcement that from then forward, the city would be the property of the Nazis. Around 2 million fled ahead of the occupation, and History adds that just three days later, the new prime minister (Marshal Henri Petain, who would go on to head France's new Vichy government) announced their surrender.

At the same time Nazi troops were moving into Paris, something else was happening, too.

According to the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum, June 14 is recognized as the official activation of the Auschwitz concentration camp. A group of 728 people from Poland — including mostly political prisoners, and a small number of Jews — were sent to the camp that day, and they would be the first of about 405,000 people to be sent there over the course of the war. Five days later — on June 19 — the first group of nearby locals was forcibly relocated to prevent any interference with prisoners or leaked reports about what was going on there. That happened anyway, when members of the Polish resistance reached out to Poland's London-based government-in-exile a few months later.

Oct. 2/Nov. 15, 1940: Warsaw Ghetto ordered and sealed

Operating alongside the concentration camps were the ghettos, or isolated districts where people — usually Jews — were forcibly relocated to. According to the Imperial War Museums, orders to create what would later become the largest ghetto in Europe were signed on Oct. 2, 1940.

It was created in a designated area of Warsaw, and all of the city's Jewish residents were given about six weeks to pick up, move, and resettle within the ghetto's limits. By the time the ghetto was officially sealed and segregated from Warsaw's Aryan sections on Nov. 15, it was home to around 460,000 people — including 85,000 under the age of 14. On the sealing of the ghetto, warnings were posted that anyone escaping or helping escapees would be executed.

And no, there definitely wasn't enough room or food. The designated area was so small that it had a population density of about 146,000 people per square kilometer, and to put that in perspective, Statista reports that in 2020, London's per square kilometer population density was 5,727 people. Most of the people there would not survive. About 20% died by July of 1942, succumbing to starvation or disease. In the months after, most survivors were sent to the Treblinka concentration camp, where 300,000 would be executed. Of the 65,639 who remained, 56,065 would be killed or deported to concentration camps in an April 19, 1943 resistance effort that ended with a mass slaughter by SS troops.

Dec. 18, 1940/June 22, 1941: Operation Barbarossa

Joseph Stalin may have ended up sitting alongside Winston Churchill and FDR, but that wasn't always the case. In fact, Imperial War Museums says that it was largely Soviet oil and grain — along with their help in dividing and conquering Poland — that supplied the Nazi war machine with the fuel it needed to get conquering in earnest. Even though they started with a non-aggression pact, Hitler had other plans that involved enslaving those in the Soviet's Slavic territories and using their expansive land as a new home for his Aryan nation.

So, on Dec. 18, 1940, Hitler made his plans to conquer the Soviet Union official with the signing of Fuhrer Directive 21. The so-called Operation Barbarossa was delayed until other campaigns were finished, and the attack wasn't launched until June 22 of the following year. When they finally did hit, they hit hard, and sent about 80% of their entire army into Soviet territory.

The Soviets were absolutely not prepared: Hundreds of thousands of POWs were taken as the German army relentlessly marched deeper into Soviet territory, Kyiv fell, Leningrad was under siege, and things weren't looking good for Moscow, either. But by then, it was November, and the Soviets' most valuable asset took the field: The weather. Even as supply lines broke down and weapons froze, Soviet resistance flared. The National WWII Museum says that of the five million German soldiers who died in the war, four million died in Operation Barbarossa.

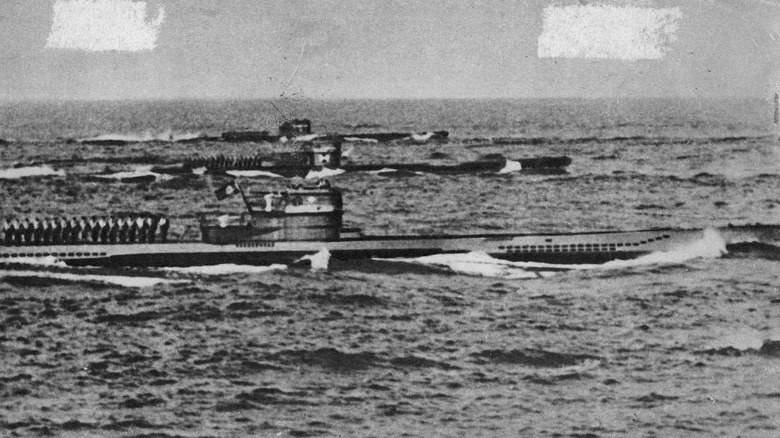

Mar. 6, 1941: Churchill names the Battle of the Atlantic

March 6, 1941 is the date that the Imperial War Museums says Winston Churchill named a battle that had been raging for years. He called it the Battle of the Atlantic, and according to New Zealand History, it had officially started on the same day the war did and would last 2,074 days. By the time it ended with Germany's surrender, it claimed the lives of around 72,000 Allied soldiers and 30,000 German ones.

The idea was pretty straightforward: Britain was heavily dependent on imports to fuel the war effort, so German U-Boats were dispatched to prowl the Atlantic and sink any Allied ships they could. The first sinking was of a passenger ship called the SS Athenia, and it happened only hours after Britain issued their formal declaration of war.

By the late 1940s, the Germans had started sending their U-boats out in groups that were quickly dubbed "wolf packs." The Canadian Encyclopedia says that even though they did most of their hunting in a stretch of ocean beyond the reach of Allied aircraft and ominously called "The Black Pit," they were so successful that they reached as far as the coastal waters of the U.S. and Canada, and even into the St. Lawrence River. For months, the Allies were fighting a losing battle. Until, that is, July 9, 1941. That, says History, is when British cryptologists cracked the Enigma code, finally giving Allied command the chance to monitor the movements and assignments of the German wolf packs.

Sept. 1, 1941: The Star of David

When it comes to the images of World War II, the yellow star is among the most famous. Still, according to The Jewish Foundation for the Righteous, it was far from the first time Jews were required to wear an identifying image on their clothing. That had been happening for hundreds of years, and the first time it happened in Nazi Germany was in November of 1938. That's when the idea was put forward by Kristallnacht engineer and SS commander Reinhard Heydrich, and it wasn't until November of the following year that the first group of Jews was forced to identify themselves by wearing the Star of David.

After starting in Poland, the laws spread to other German-occupied territories. Somewhat surprisingly, it wasn't until Sept. 1, 1941, that the Nazis issued a formal order that Jews more than 6 years old and living in Germany would also be required to wear the yellow star. The law also specified that it was to be yellow, have six points, four inches in diameter, and be clearly visible on both the back and the left side of the chest.

Sept. 19/29,1941: Germany massacres Kyiv

Ukraine's Jewish community had suffered hundreds of years of persecution, since their settlement there in the 8th century. Caught in the middle of Operation Barbarossa, things only got worse. Then, at the end of Sept. 1941, Babi Yar became the site of what the Holocaust Memorial Day Trust calls one of the deadliest, single massacres in the war.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum says that it started on Sept. 19 with the Nazi's advance into and occupation of Kyiv, a city whose population was about 20% Jewish. Although tens of thousands fled in advance of the army, there were still scores of people left. Not long after the Nazis secured their foothold, posted instructions started showing up around the city telling all Jewish citizens to report to a ravine called Babi Yar on the morning of Sept. 29. Raisa Maistrenko later explained, "All the Jews decided to go because they thought they would be evacuated by train as the railway station was nearby. Nobody could possibly assume there would be a mass execution."

But there was, and according to The Jewish Virtual Library, 33,771 people were executed over the course of two days. Maistrenko was one of only 29 survivors, and the ravine remained a site for later mass executions. It was later estimated that by the end of the war, more than 100,000 people died there.

Mar. 25, 1942: The first Jewish prisoners are sent to Auschwitz

By the time the first Jewish prisoners were sent to Auschwitz, the camp had been operational for more than two years. According to National Geographic, the first official transport of Jewish prisoners to the camp involved 999 women, all of whom had complied with posted instructions that all Jewish, unmarried women over the age of 16 had to report for unspecified work duty. They were stripped, examined, loaded onto passenger cars, and taken to a nearby army barracks.

More trains — also filled with young, unmarried Jewish girls, arrived in the following days. They were then loaded into train cars, and there were a few reasons that the first transport was made of young women: Historians believe that they were chosen to be used essentially as bait, with the idea that promises of a reunion with daughters would make families more likely to follow.

It wasn't long before the girls started to die, with some weakening from back-breaking labor that included the construction of buildings that ended up serving as gas chambers and a crematorium. Edith Grosman was one of the few that survived until liberation, saying: "We opened and closed Auschwitz. ... The guilt of the survivor — it never goes away. ... Why else did we live but to tell?"

May 27/June 9, 1942: Reinhard Heydrich's assassination/Destruction of Lidice

SS General Reinhard Heydrich had a whole list of titles, but the bottom line is that he was pretty high up on the Nazi food chain, and was one of those responsible for the design of the so-called Final Solution.

In spite of the fact that he firmly believed he had so completely pressed everyone under his bootheel that no one would dare to try anything out of line, he was still the target of an assassination attempt on May 27, 1942. Two Czech resistance fighters tossed grenades under his car, and although he survived the explosion, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum says that it led to an infection and his death on June 4.

Reprisal was swift, and on June 9, the SS headed into the town of Lidice with claims of a connection to the assassins. (It wasn't true — the assassination had been planned in London as a joint British and Czech plan called Operation Anthropoid.) Hitler had demanded the deaths of 10,000 Czech citizens, and Lidice was targeted for annihilation somewhat arbitrarily. The town of 500 was burned to the ground, the men and boys executed, the women sent to Ravensbruck, and the children evaluated for either euthanasia or suitability to be Germanized and adopted through the Lebensborn program. Reprisals continued with the village of Lezaky, and thousands died before the SS was satisfied.

Feb. 2, 1943: The end of the Battle of Stalingrad

The Journal of Military and Veterans' Health calls the end of the Battle of Stalingrad one of the most important moments of the war. The Surrender of German commander Field Marshal Friedrich Paulus marked the end of Germany's march into the Soviet Union and the start of their retreat back to Germany. To add insult to injury, the surrender also handed the German army their largest defeat to date, with 91,000 soldiers taken as POWs and half a million dead (via the Imperial War Museums).

The sheer size of the conflict is still shocking: More than four million soldiers were involved, casualties would top 1.8 million, and according to Ohio State University, Operation Barbarossa had become the largest military conflict in history. More Soviet soldiers died in the five months prior to surrender than Americans died throughout the entire war, but still, continued Soviet resistance — and help from the weather — broke the German army so thoroughly that they would never recover.

Sept. 3/8, 1943: Italy surrenders

Benito Mussolini may have had a friend in Adolf Hitler, but he didn't have many among his own people. Major military defeats led to a loss in confidence and his replacement in July of 1943, and on Sept. 8, 1943, it was announced (via the BBC) that Mussolini's replacement, Marshal Pietro Badoglio, had signed (via proxy) an unconditional surrender to the Allied army five days prior.

In the announcement to the Italian people, it was made perfectly clear that they now had the support of the Allies and the United Nations against any Germans who remained, and Hitler was quick to make it clear that he hadn't forgotten his old friend. Mussolini was spirited away by the Nazis on Sept. 12 and installed at the head of a puppet government in northern Italy, which would ultimately work out for no one. Meanwhile, Allied leaders were just as quick to warn that although this was the end of the Axis triumvirate, it wasn't the end of the war.

June 6, 1944: D-Day

Even before the surrender of Italy, Allied forces had been planning a massive operation to free France from Nazi occupation. The plans that would become D-Day started back in July of 1943, says English Heritage, with the formation of an intelligence network called the London Controlling Section, and their brainchild: Operation Bodyguard.

Before any operation into occupied France could even be considered, they needed to lay the groundwork for deception. The Nazis couldn't know where and when the invasion was going to happen, so it fell to MI5 and a network of spies to spread the word that the Allies were going to be targeting Pas-de-Calais.

They, of course, were not, and the deception did exactly what the Allies had hoped it would. They headed for Normandy, a single point along a coastline that had been reinforced with tank ditches, outposts, pillboxes, heavy artillery, and around 6.5 million mines. Originally scheduled for May 1(ish), then more firmly for June 5, bad weather delayed the invasion by a day. Once the orders were given to go, the largest amphibious invasion in history kicked off: The National WWII Museum says that the initial landing involved 175,000 troops, 50,000 vehicles, and another million that landed in the following months. If it had failed, future failures would have been inevitable.

July 22/23, 1944: Liberation of Majdanek

With German forces largely on the defense, Allied troops were advancing through territory once held by the Nazis. Over the night of July 22 to 23, 1944, it was Soviet troops who marched into one of the most horrific scenes throughout the war: A concentration camp.

That night, Majdanek became the first camp to be liberated by the Soviets, who found many of the remaining prisoners were some of their own missing soldiers, taken as POWs and sent to the camp. Although many had been evacuated and transferred to other camps ahead of the advancing Allies, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum says that the camp itself was virtually intact — and it was very, very clear what had been happening there. Journalists were invited in to see the horrors first-hand, and it wasn't long before they had very real confirmation that it wasn't the only camp of its kind.

More camps would be liberated as the Allied forces marched on: Soviet troops would liberate Auschwitz on Jan. 27, 1945, followed by Ravensbruck, Stutthof, and Sachsenhausen. It wasn't until April of 1945 that U.S. troops stumbled across their first camp, and liberated Ohrdruf (near Buchenwald). That was followed by the rest of Buchenwald and Dachau (pictured), while the same month, the British liberated Bergen-Belsen.

Aug. 4, 1944: Anne Frank captured

Anne Frank's diary remains one of the most widely-read personal accounts of the war, and to put the tragedy of her life and death into perspective, it's important to touch on the fact that by the time she and her family were captured on Aug. 4, 1944, the Allied forces had just begun liberating concentration camps.

The Frank family had gone into hiding more than two years prior to their capture: On July 6, 1942, they came to the horrifying realization that they weren't going to be allowed to emigrate, and had no choice but to try to hide. Several others joined them, and Anne documented the days spent in hiding, in hunger, and in fear with an openness that remains one of the most candid glimpses into life during the war.

After remaining undetected for years, a joint raid by Dutch police and Nazi enforcers lead to their capture, and almost a month later — on Sept. 3, 1944 — they would be taken to Auschwitz. The Anne Frank House says that Anne would eventually be transferred to Bergen-Belsen, where she would die in February of 1945: The camp would be liberated by British forces on April 15 (via Imperial War Museums). Anne's father, Otto, would be the only family member to survive.

Apr. 28/30, 1945: Mussolini dies, Hitler commits suicide

When The New York Times reported on the death of Italy's Benito Mussolini, they called it (via The National WWII Museum) "A fitting end to a wretched life. The man who once boasted that he was going to restore the glories of ancient Rome is now a corpse in a public square in Milan, with a howling mob cursing and kicking and spitting on his remains." Mussolini had tried to escape the now-relentless forward march of the Allies, but was recognized, executed, and — alongside his mistress — hung upside-down in front of a nearby gas station. The crowd did more than kick and spit, with at least one woman putting five bullets into his corpse — one for each one of the sons she'd lost.

News of Mussolini's death reached Hitler, who was cowering in his underground bunker, hiding from the Soviets who swarmed the city in search of him. When word of the desecration followed, it perhaps wasn't entirely surprising that on Apr. 30, Hitler and Eva Braun committed suicide after first killing Hitler's dog, Blondi (pictured), to make sure the poison capsules were going to work.

Winston Churchill described the scene: "The bodies were burnt in the courtyard, and Hitler's funeral pyre, with the din of Russian guns growing ever louder, made a lurid end of the Third Reich."

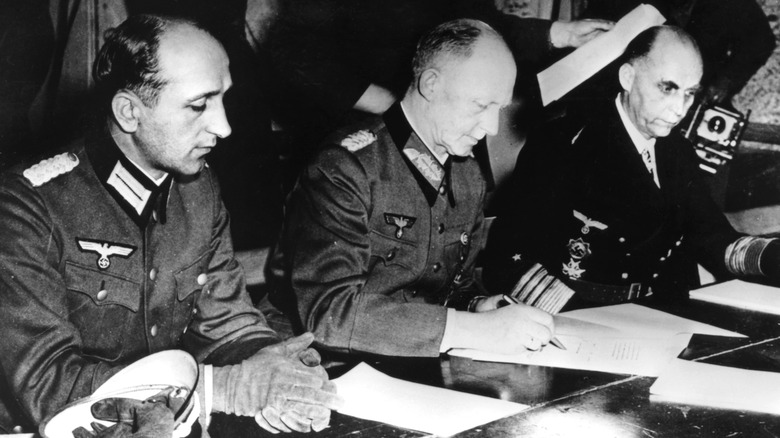

May 7/9, 1945: Germany surrenders

Germany, says National Geographic, brought an official end to the war by surrendering not once, but twice. The first was on May 7 in Reims, France (pictured), with the second taking place in Berlin two days later. Why?

Before committing suicide, Adolf Hitler appointed a successor. That was Karl Donitz, who made negotiating the terms of surrender one of his first actions. The first surrender was signed by the man Donitz recently named chief of the operations staff of the Armed Forces High Command, Alfred Jodl. All seemed well and fine, but the Soviets had some serious issues with the location (saying that they should be forced to surrender in their capital city), and the signer, pointing out that while Jodl was high-ranking, he wasn't the highest. It was a situation reminiscent of the surrender that ended World War I, and no one wanted to leave any doors open.

So, a second surrender was signed in Berlin, by the German army's top official: Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel. This time, the war was officially over.

Oct. 18, 1945: The Nuremberg Trials

Given the sheer scale of what had transpired throughout the war, it's surprising that things post-war moved so quickly in regards to putting some of the highest-ranking Nazis on trial for their crimes. By Aug. 8, the Allies had formed the International Military Tribunal, and that was swiftly followed by official charges issued against 24 of the biggest players of the Third Reich. On Oct. 18, the list of defendants — which included Rudolf Hess, Hermann Goring, Albert Speer, and Karl Donitz — was charged with crimes against humanity, defined (via The National WWII Museum) as "murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation... or persecutions on political, racial, or religious grounds."

The trial itself ran from Nov. 20, 1945, to Oct. 1, 1946, resulting in 19 convictions and 12 executions, which were carried out just 12 days later.

A series of 12 other Nuremberg Trials followed: According to The Holocaust Exhibition and Learning Centre, these were overseen not by the Allied tribunal, but by the American military. Among those put on trial were the doctors behind the Nazi's euthanasia program, several industrialists who were accused of using slave labor, the heads of the Nazis' mobile killing squads, and the creators of Zyklon B. These trials didn't end until April of 1945; trials connected to various concentration camps were held outside of Nuremberg, and other Nazi war criminals have continued to face justice into the 21st century.